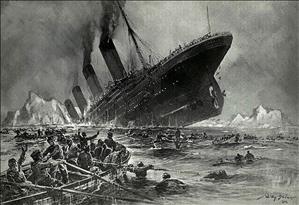

On April 10, 1912, the Titanic, at the time the largest and most luxurious ocean liner ever built, departs on its maiden voyage from Southampton, England. There are six people on board with connections to King County, Washington. At 20 minutes before midnight on April 14, the ship hits an iceberg. By 2 a.m. the Titanic sinks. Of the approximately 2,205 passengers and crew some 1,500 people drown. There are 705 survivors, including two passengers headed for Seattle. This is the greatest sea disaster in history.

There were six people on board with connections to King County, Washington.

- William Harbeck, Seattle resident, moving picture producer and cameraman, was on the Titanic as its official filmmaker. He had filmed the progress of Seattle’s regrading project on Denny Hill, as well as the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition.

- Hugh R. Rood lived in Seattle and served as Vice President and General Manager of the Pacific Creosoting Company, a firm that creosoted pilings to protect them from shipworms.

- Herman Klaber was a King County businessman known as the “hop king” because he operated the largest hop business in America, providing the main ingredient for beer.

- The Brown family, including Thomas Solomon William Brown, a real estate investor in Cape Town, South Africa, his wife Elizabeth Catherine Brown, and daughter Edith Eileen Brown. They were traveling to Seattle to visit a sister, Mrs. Josephine Acton, and possibly to live here.

At noon the Titanic cast off and headed for Cherbourg, France, and Queenstown, Ireland, to pick up passengers before steaming across the Atlantic for New York City. The Titanic left Queenstown the following day carrying about 1,313 passengers and a crew of 892.

On April 14, 1912, just before midnight, about 1,000 miles east of Newfoundland, Canada, a slight jolt was felt throughout the ship. The engines stopped. The Titanic had hit an iceberg. An hour later the first lifeboat was lowered to the Atlantic. By 2:05 a.m. on April 15, 1912, the last lifeboat had pulled away. Twelve minutes later, the largest ship yet built was slipping below the frigid waters of the North Atlantic. Her crew sent out a final wireless message: “We are sinking fast. We cannot last much longer.”

Klaber Homesick and Going Home

Klaber, the "hop king" of Lewis County had been in Europe on business for three months when he finally got homesick for his wife and small child and decided to return home. A few days before he boarded the Titanic, he wrote his friend and business partner Ben Moyses, a co-owner with Klaber of Seattle’s Independent Brewing Company. He wrote:

“I have determined to leave here for home on the new steamship Titanic. The other day I was sitting in a leading hotel here and noticed a man reading what looked like an American newspaper. I ‘rubbered’ over his shoulder and found that it was a copy of The Seattle Times. My, it looked good to me to see a Seattle newspaper here in London. I introduced myself and found that I was talking to a Seattle business man, W. R. Owens, and we spent five hours together talking about 'God’s country.' I hope to be there soon and I shall leave here as soon as I can make arrangements" (The Seattle Times).

Tragically, Herman Klaber did indeed end up in "God's Country" though not his cherished home. He as well as Hugh Rood, William Harbeck, and Thomas Solomon William Brown perished in the disaster. Brown's wife and daughter lived to tell their own sad tale.

Mother and Daughter Survive

Elizabeth Brown and her daughter Edith were among those who got into lifeboats and were saved. After mother and daughter arrived in Seattle, Elizabeth Brown told her story to a Seattle Post-Intelligencer reporter. On the evening of April 14, 1912, the Browns turned in early. Near midnight, the Titanic hit something on the starboard (right) side that sent a shudder through the ship. Elizabeth Brown stated,

“I was awakened by a shock. It seemed quite violent to me. The engines were stopped and the ship seemed very quiet at first. I feared at once that there had been an accident. The passengers had seen reports about icebergs on the ship’s bulletins... . My first thought was we have struck an iceberg. I put on some clothes and told my daughter to dress. I went at once to my husband’s stateroom and found him still sleeping... . He did not think the situation was dangerous, but I urged him to go on deck and find out what had happened.”

About an hour after striking the iceberg, the passengers began getting into lifeboats, with women and children first. Elizabeth and her daughter Edith got on Lifeboat 14, the second lifeboat to be launched. Elizabeth Brown described her husband’s reaction after they got on the boat:

“My husband turned away without a word. I supposed at first he would follow us into the boat... . They began to lower the boat over the side. It seemed a terrible distance. I looked back for my husband. I saw him turning away. We never said goodbye” (Seattle Post-Intelligencer).