On June 17, 1926, a carpenter walking the north end of Seattle's Green Lake on his way to work finds a pair of women's shoes in an alder grove on a point of land next to the lake. He walks a few feet farther and finds a dead woman, nearly naked and sprawled near the shore. The dead woman is Sylvia Gaines, 22, and police soon zero in on a suspect: her father. The Gaines affair will become one of the most sensational murder cases in Seattle's history.

Seattle Was Shocked

From the moment Sylvia Gaines' body was discovered, the Gaines murder case became one of the most sensational in Seattle's history. Gaines was young, attractive, and intelligent, a graduate of the elite Eastern women's college Smith. And she had a prominent relative in Seattle: her father's brother, William Gaines, was the chair of the King County Board of Commissioners.

The funeral was held on July 10, 1926. Wallace C. "Bob" Gaines, Sylvia's father, was by then the prime suspect but was permitted to attend. He showed no emotion, but his brother wept. The murder case was front page news for months. Seattle was shocked and fascinated by the sordid details that emerged about the victim's life and death.

Sylvia Gaines was born in Massachusetts in 1904. Her parents split in 1909, when her father came to Washington, leaving Sylvia and her mother behind. Shortly afterward, the couple divorced. In September 1925, Sylvia, having graduated from Smith College, came to Seattle to visit her father, whom she barely knew. Fewer than 10 months after her arrival, she was murdered. The prime suspect was Bob Gaines, a World War I veteran.

At first police did not suspect him. On June 17, 1926, Bob Gaines reported his daughter missing, and after her body was found, he identified her at the morgue. Ewing Colvin, the King County Prosecutor (and a good friend of Bob Gaines' brother William) thought Bob Gaines innocent -- for what father would kill his child? -- and thought it likely that some fiend had assaulted and killed Sylvia. But evidence kept pointing to Bob Gaines as the murderer. When authorities questioned Gaines on the morning of June 17, he was intoxicated and made statements suggesting that he knew who the murderer was. Investigators turned up several of Gaines' neighbors and friends who saw him on the night of the murder, very drunk and disturbed at his daughter's disappearance.

Gaines was charged with murder. His trial began on August 2, 1926. The prosecutor asked for the death penalty. A jury was chosen, consisting of nine men and three women. The women jurors got a lot of attention from the press because, although women had received the vote in 1920, many states prohibited them from serving on juries -- a prohibition that continued in some states into the 1940s. Media and public attention was so intense that the judge ordered the jury sequestered in a downtown Seattle hotel.

Ewing Colvin Prosecutes

Prosecutor Colvin called witnesses to testify about the events of the evening of June 16. He quickly demolished the "fiend theory" that a stranger had raped and killed Sylvia Gaines. No one -- neither neighbors nor people walking by the lake near the murder site -- had heard any outcry. This made it likely that Sylvia was killed not by a stranger, but by someone she knew and had no reason to fear.

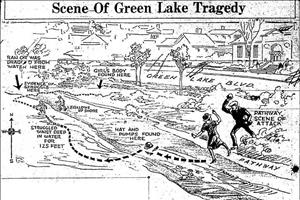

Witnesses reported seeing Bob Gaines at the lake shore around 9 p.m. that evening, near where Sylvia's body was later found. He was bending down over someone or something. Other witnesses said they'd seen Gaines drive around the lake several times about the time of the murder. Sylvia was strangled and her head battered with a blunt instrument. She died around 9 p.m. Authorities found a bloody rock near the murder site. Testimony established that she had been murdered in one spot and that her body had been dragged to another, several yards away, and arranged in a manner to suggest sexual assault.

Bob Gaines testified that he and Sylvia had quarreled on the evening of June 16. Sylvia, in an angry mood, left their home at 108 N 51st Street shortly after 8 p.m. for a walk around the lake. Gaines said he left at about 8:40 p.m. when he drove around nearby streets looking for her and then drove to the home of his friend and drinking companion, Louis Stern. He arrived there about 9:30 p.m.

Stern's evidence was damning. He reported that Gaines came to his house to drink and all but confessed that he'd murdered his daughter. According to Stern, Gaines said, "You know what I have always told you, that if anyone in my house told me when I should come and go and when I should drink and how much, why I would kill 'em. ... Well, that's what happened."

An Unnatural Relationship

Colvin had established where, when, and how Sylvia Gaines had been killed, but he had to provide a motive. Colvin's theory was that Gaines and his daughter had what was then called an "unnatural" relationship. Gaines knew that Sylvia wanted to leave his home -- she had made plans to go stay with her uncle William Gaines -- and he killed her to keep her from leaving him or revealing their incestuous affair.

According to Colvin, the "unnatural relations" had evidently been going on for most of Sylvia's visit. She came to Seattle in September 1925 to get to know her father. She and her father had not seen each other since 1909, when she was 5 years old. Sylvia moved in with her father and his second wife; they lived in a small one-bedroom house. When Sylvia arrived, she slept on the couch in the living room while her father and his wife slept in the bedroom. The three of them quarreled frequently. Evidently Mrs. Gaines was distraught about the situation, and in November 1925, she tried to kill herself. At that time, Sylvia and her father were threatening to leave the home and get an apartment.

Gaines' neighbor said she had believed the two were sharing a bed and that Mrs. Gaines slept on the couch. Other witnesses described angry quarrels that erupted between Bob Gaines and Sylvia in public. A Seattle patrolman had discovered Gaines and his daughter late at night parked in Gaines' car in Woodland Park -- as teenaged lovers might. An employee of a downtown Seattle hotel testified that in November 1925 she had seen Gaines and his daughter -- in their nightclothes -- together in bed.

In his closing statement, Colvin argued that Gaines had been sexually involved with his daughter for some months, and that she was fed up and about to leave. On the evening of June 16, they quarreled, and Sylvia left the house to get away from him. Gaines went after her, found her walking near Green Lake and, in a jealous, alcoholic rage, killed her. Then, to make it look like she'd been raped and killed, he tore her clothes, dragged her body nearer the path and arranged her limbs in a manner to suggest sexual attack. He continued to drink heavily and confessed the murder to his friend Louis Stern.

A Murderer Is Hanged

The jury deliberated a little over three hours and found Gaines guilty. He was sentenced to die. He appealed his case but was unsuccessful. On August 31, 1928, in Walla Walla, he was hanged. Following the execution, his body was transported to the Veterans Memorial Cemetery at Evergreen-Washelli Memorial Park, 11111 Aurora Avenue N, Seattle, for burial with full military honors (usually conducted by the American Legion).

Sylvia Gaines' remains were cremated and Butterworth Mortuary sent her ashes to her mother in South Lynfield, Massachusetts.

The grove of alder trees near where Sylvia's body was found is gone, replaced by more than 30 black cottonwoods (Populus trichcarpal). Local legend has it that the community planted the cottonwoods on what is now called Gaines Point, in memory of Sylvia Gaines. Those cottonwood trees grew to be about 70 years old, and provided roosting places for bald eagles, and other raptors. In 1999, the Seattle Parks Department decreed that the trees must go because mature cottonwoods drop limbs and threaten public safety. The Parks Department clear-cut the grove and replaced the cottonwoods with Populus x Robusta, which like other poplars is fast growing but has proven to be more durable.

Thus has the last physical reminder of this sad piece of Seattle history been removed.