The roots of Trager USA in Monroe, Snohomish County, trace back to Lloyd F. Nelson (1894?-1986) of Bremerton, Kitsap County. Nelson was working in Alaska in 1920 when he decided to enjoy a hike into the backwoods. Borrowing an old Inuit backpack made of sticks and sealskin, he set off overland, returning bruised, tired, and sore. Once home, he designed a more comfortable version of the pack. It was constructed of a rigid wooden frame that boasted a detachable canvas sack and soft shoulder-straps. When marketed, "Trapper Nelson's Indian Pack Board" was the earliest example of a mass-produced external-frame pack, making Nelson the father of the modern outdoor-gear industry. The state-of-the-art pack earned design patents and soon became a trail staple for the Boy Scouts and the U.S. Forest Service. In 1929, Nelson sold out to his partner, Charles Trager (1876-1959). The Trager Manufacturing Company went on, under Charles's son George Trager (1915-1985), to supply gear to Eddie Bauer and REI and to various Mount Everest expeditions. In 1980 the firm was sold and in 2004 it was recast as Trager USA, a vendor of daypacks, travel bags, and laptop cases, but the Tragers deserve much credit for dramatically expanding the entire outdoor-gear industry.

"Trapper" Nelson and His Pack Board

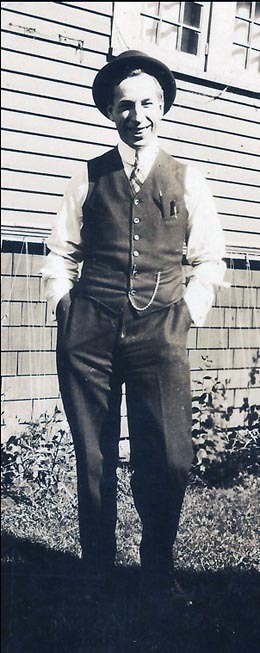

Lloyd F. Nelson was born around 1894. He took up trapping wild game while being raised in Oklahoma before the family moved to the Puget Sound area in 1908. In time he began working at the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Bremerton, married Sylvia Farrow Nelson (d. 1981), and with her raised their daughter, Lois. An inventive problem-solver by nature, Nelson earned his first design patent (No. 1,303,944) from the U.S. Patent Office on May 20, 1919, for an invention described as a "combination pencil and scribe." Nelson loved the outdoors and for decades his name would often be noted in the newspapers for success in various fishing derbies. It was in the spring of 1920 that, as Nelson once recalled:

"I ... was sent [by the shipyard] to Wood Island, near Kodiak, Alaska, to check shortages on a construction job. When my work was finished, I asked for and received, a short leave without pay, and joined the throngs of miners, fishermen and other foot-loose Alaskans who were staking claims on newly opened oil-reserve land. While assembling an outfit to enable me to cross a mountain range on foot, an Indian agreed to lend me his crude Indian pack board made of sealskins stretched over willow sticks, a style used by generations of his ancestors. I made the trip and staked my claim, but afterwards lay awake nights recalling the back-breaking ordeal and wondering if it would be possible to evolve a really comfortable backpacking device. While waiting on Wood Island for the ship that came once a month, I put together my prototype of a scientific pack-board frame, and thus began a project which kept me 'burning midnight oil' for the next nine years!" (Widrig).

By the time Nelson returned home to Bremerton, he had decided to explore the combined pack-board/knapsack concept further, by creating a workshop space in his basement. Then "I made a trip to Seattle and purchased a power sewing machine and a bolt of canvas, thread, grommet, dies, cord, buckles and a side of leather and a cutter. Next, I asked a young man, J. D. (Dorm) Braman, then working at the Braman Mill in Bremerton ..., to turn out material enough to make a dozen pack-board frames according to my instructions" (Widrig).

That woodworker, James d'Orma "Dorm" Braman (1901-1980), who would later serve as mayor of Seattle (1964-1969), was tasked with "turning out strips of ash and oak to make the frames ... The thin pieces of oak were soaked in hot water in Mrs. Braman's wash boiler so they could be bent to the right shape" ("Bramans Once Helped ... "). The "right shape" for those strips (which elsewhere have been identified as being spruce) were of a pronounced arch that would, when assembled into a pack frame, sit nicely in adjacency to a curved human back contour. At least that was Nelson's theory. He later recounted:

"The next step was learning how to operate my sewing machine ... . My initial attempts were crude as I worked out a pattern for the bags and experimented with mounting them on the frames. Frank Aubrey, a friend, became interested in my idea, and we tested the packs on long walks and mountain trips, while I tried to achieve free body movement and ideal weight distribution. We carried blankets and canned food — and sometimes even added rocks for weight!

"Meanwhile, I changed and improved my design ... . I added an outside pocket to the bag for handy access to small objects and I increased the size of the flap to cover a bedding roll laid across the top of the pack.

"When the first dozen were assembled, I looked over the array — and cut them up and burned them in the furnace ... . Then I went back to Dorm and ordered another dozen frames" (Widrig).

With a refined design and more skillful workmanship, the second dozen Nelson built looked more promising. So he filled one up with camping gear, strapped it on, and headed out for a visit to every sporting-goods store and hardware shop in Bremerton and Seattle. Four decades later, an apparently still-frustrated Nelson remembered, "Everyone was interested, but no one would buy one ... The consensus was that my product was too good-looking for the type of person who carries food, clothes, and blankets from place to place. The best I could do was leave my samples on consignment" (Widrig). But then those consigned packs began to sell and Nelson figured he just needed to advertise their existence better. With pack on back once again he marched right into the offices of the Pacific National Advertising Agency, where he explained to William H. "Bill" Horsley (d. 1966) that he wanted some brochures or folders designed and printed up.

"As I was leaving, Horsley asked what I wanted to name the product, and I said 'Anything you like — you're the advertising man.' When I returned a week later, Horsley had coined the name, 'Trapper Nelson's Indian Pack Boards'" (Reddin).

On July 31, 1922, Nelson filed a patent application with the United States Patent Office for his pack. U.S. Patent No. 1,505,661 was granted on August 19, 1924, and Canadian Patent No. 244902 came through that same year. The Trapper Nelson logo was designed, the informational folders printed, and Nelson began mailing them off to far-flung sporting-goods stores and contacting various outdoors-oriented organizations including the Boy Scouts and the U.S. Forest Service. Then Nelson hit the highway for 35 days with his wife and daughter and a carload of packs in tow, stopping at every sporting-goods shop between Seattle and San Diego, camping the whole way.

The key attribute of the pack was a simple design that distributed a load's weight fairly evenly, increased air ventilation via an empty space between its canvas jacket and a hiker's back, and made loading the pack easier via its detachable bag. One technology historian notes that "By modern standards, the pack is cruel and unusual torture, but compared to the alternatives at the time, it was a big improvement" (Shaver). Another concurs: "Though considered crude by today's standards, the Trapper Nelson represented a breakthrough in pack design" ("Packboard Restoration").

Priced right -- different sizes of the packs went for $5.50 (S), $6.50 (M), and $7.50 (L) -- the sales of Trapper Nelsons increased enough that Nelson was soon able to subcontract for the manufacture of the canvas-based components. Thus an arrangement was soon made with a local businessman, Charles Trager (1876-1962), to have the pack-sacks sewn in a downtown Seattle factory.

Trager Manufacturing Co.

Charles Trager was the son of a German immigrant, George Trager, who had settled in Gloversville, New York, where he was employed in the town's core industry -- making leather gloves. At age 15 Charles, who had also learned the trade, left home and eventually wound up in San Francisco, where he got caught up in the frenzy of supplying the prospectors heading to the Klondike Gold Rush (1896-1899). One of the products he made was a soft leather "gold poke," or nugget pouch, replete with a drawstring. Trager reportedly arrived in Seattle in 1901, where he and a partner, Henry W. Nagel, founded the Nagel and Trager Company (2204 1st Avenue, Baker Building), which went from glove manufacturing to producing other items, including leather aprons and bags, for gold prospectors.

Trager helped Nelson by refining the manufacturing process for his packs, and soon they joined forces as partners. But, as camping and hiking were not yet a common family activity, popularizing the packs was still an uphill climb for the enterprise. As the following years sped by, Nelson's investment of time, energy, and money was taking its toll on him. As he later explained, "Sales were slow. I did everything I could to promote the pack boards, but I couldn't break even. In the summer of 1929 I sold the business for $5,000 to ... Charles Trager" (Reddin). But, as Nelson said:

"Fate is peculiar ... Two weeks later, I received a rush order from the Forest Service at Missoula. They wanted 500 pack boards to equip forest rangers and forest-fighters. Within a fortnight, another rush order came for 500 more from the Forest Service at Salem, Ore.! A pall of smoke hung over the Pacific Northwest, and the ill wind that fanned the fires proved to be a boon to my pack boards. Movie newsreels showed scores of men equipped with 'Trapper Nelson' pack boards. At last they had reached the public eye!" (Widrig).

As the inventor recalled it, "the Trapper Nelson soon thereafter became the best-known pack board in the country" (Reddin). Referring to his initial invention nearly a decade earlier, he concluded, "I was nine years ahead of my time" (Reddin).

Nelson went on to work for the next 30 years as assistant industrial manager and inspector of new construction at the Bremerton naval yard. In time he bought a summer home in Bellevue, and he and Sylvia resettled in Seattle at 2167 Dexter Avenue N, where he proudly listed his telephone number under the name "Lloyd Trapper Nelson" -- and where he was interviewed about his backpacks in 1961 and 1966 by The Seattle Times.

Meanwhile Trager forged ahead, eventually getting the packs into Seattle stores ranging from J. Warshal and Sons (1st Avenue and Madison Street) to Seattle Sporting Goods, Ben Paris's Recreation, Osborn & Ulland Inc., Sears Roebuck & Co., and the upscale Frederick & Nelson department store. In time, arrangements were made to have the Jones Tent & Awning company in Vancouver, Canada, produce Pioneer Brand Trapper Nelson Indian Pack Boards for sale there. Then, by the mid-1950s, various other companies began marketing knockoff "Trapper Nelson-type" packs, causing Trager to begin calling his product "Genuine" Trapper Nelson packs.

The packs began to sell in remarkable quantities to everyone from the U.S. Forest Service to the Department of the Interior, the U.S. Geological Survey, the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, and even the U.S. Army Mapping Service. Then orders for many more began streaming in from around the world, including one particularly large order from Ethiopia's Abyssinian Water Development Commission. Along the way, Trapper Nelson packs were adopted by many Boy Scout troops, and the brand name was one that signified quality for generations of Tenderfoot as well as Eagle Scouts.

And thus the packs became ubiquitous on riverside trails, mountaintops, and deserts far and wide. In the 1960s Seattle Mayor Dorm Braman told The Seattle Daily Times that "It's still the best packboard made" ("Bramans Once Helped ... "), and that newspaper's beloved columnist Don Duncan confessed to his readers that "My boyhood dream was to own a Trapper Nelson pack-board -- then the ultimate in back-packing gear" (Duncan, "Seattleite's ..."). Another time he waxed poetic about his love of hiking and camping, writing that "When my wife brands me 'an overgrown Boy Scout,' I hoist my ancient Trapper Nelson pack in a toast to all who prefer woodland trails to the most brilliant freeway cloverleaf devised by man" (Duncan, "Show ...").

The Last Trapper Nelson

Charles Trager had married Madeline W. Gillespie and they had a son, George Leighton Trager (1915-1986). The family lived at 320 W Galer Street on Queen Anne Hill and George grew up working at his father's factory -- called the Trager Glove Co. after 1930 -- and graduated from Queen Anne High School in 1933. He then attended the University of Washington. But around 1938, when he was just one quarter shy of graduating, Charles insisted that George, who lived with his parents at their then home (2205 2nd Avenue W), quit school and come work full-time as a salesman at the family business. In 1939, George married Helen Shildmyer. They bought a home (2534 12th Avenue W) in August 1940 and were later blessed with a daughter, Paige Trager (b. 1946).

George Trager ended up buying his father's company outright, and eventually it began making additional gear, including tents and sleeping bags. Around 1948, he and Gordon L. Hayes founded the Trager-Hayes Manufacturing Co. (2205 1st Avenue), which provided upholstering services and received a bit of newspaper coverage when the men took on the curious task of refurbishing old pianos by adding padded upholstery to their exterior surfaces. Trager also launched side-products, including an inflatable life-preserver vest named the "Charlie Buoy" and in 1950 a racquet-and-ball lawn game called "Wiskit." Along the way Trager became a very prominent citizen of Seattle, one whose large circle of friends included everyone from Rainiers' baseball star Edo Vanni to restaurateur Peter Canlis and longtime Seattle Times columnist John J. Reddin.

By 1951 the firm had been recast as the Trager Manufacturing Co., and George and Helen had moved to a new residence at 4020 E 85th Street. Around 1963, when the company began advertising itself as a "sporting goods" concern, its factory was moved into the circa-1919 John Graham Sr.-designed Oceanic Building at 1300 Western Avenue.

Trager outdoor gear received positive notoriety among mountaineers when it was deemed the best available for Jim Whittaker's (b. 1929) successful Mount Everest Expedition of 1963. Since 1955 Whittaker had been an employee of Seattle's REI Co-op (later Recreational Equipment, Inc.), a consumer's cooperative that had been founded by Lloyd Anderson in 1938. REI (then located at 11th Avenue and E Pine Street on Capitol Hill) was also one of the big-time retailers -- eventually also including the Eddie Bauer Co., L.L Bean, Roffe, and Abercrombie & Fitch -- that would contract with Trager to have custom-branded gear made for them.

Trager and Whittaker became business partners in 1967 and one floor of the Oceanic Building became home base to the THAW Manufacturing Co., Inc., which began supplying REI with goose-down sleeping bags (and later, vests and parkas). The acronymic corporate name was derived from the initials of the surnames of its founders: Trager, Hartsfield, Anderson, and Whittaker. Anderson and Whittaker were REI bigwigs, and John Hartsfield was a Trager factory supervisor who had joined the firm in 1958. Trager served as president, Whittaker as vice president, and Hartsfield as secretary-treasurer. REI, where Whittaker worked until 1971, initially owned 50 percent of THAW, but in September 1973 Trager and Hartsfield sold their shares of the 100-employee company to REI.

Meanwhile, in the late 1960s Trager foresaw a potential new market for his products -- in particular a series of light frameless daypacks. That's when he hired a new salesman to make contact with university-area bookstores and push the idea of selling those daypacks to students for hauling around their textbooks. Thus by the early 1970s demand for old-school canvas Trapper Nelson packs was diminishing in favor of these more modern designs made from synthetic Cordura fabric. Business was good. Indeed, according to George's grandson, Rick Trager (b. 1968), the General Mills Corp. made Trager a $6 million buy-out offer in 1972 but George passed. That same year George told The Seattle Daily Times that the business was modernizing, yet it continued to manufacture Trapper Nelsons: "I suppose we make up about 1,000 a year now. Mostly for sentimentalists" (Duncan, "Seattleite's ...").

In 1978 the factory moved once again, to its own building at 90 S. Dearborn Avenue, adjacent to the Alaskan Way viaduct and near the new Kingdome sports stadium. In 1979 Trager hired John Tanner, in 1980 the company was sold to John Hartsfield, and then George Trager retired. Sort of: Well into the 1980s he still showed up at the factory to look things over. In fact, not long before his death in 1986 Trager dropped in and discovered that his high school-aged grandson Rick, who worked there during the summers of 1984 to 1987, had grabbed a set of components from the warehouse and cobbled together his own Trapper Nelson pack just for fun. But seeing that Rick had done it incorrectly, George cheerfully headed towards a factory workbench, disassembled it, and the two worked to build what would be the last Trapper Nelson pack ever made.

Trager and Trapper Nelson's Legacy

The original Trapper Nelson backpacks had a big influence on the thinking of numerous subsequent outdoor-gear companies both local and distant. Building upon the original idea, California's Dick Kelty contributed the idea of adding a hip belt in the 1950s, and his Kelty brand later innovated the use of an aluminum frame and a nylon fabric pack-sack. Later, Seattle's Murray Pletz won a design contest sponsored by the Pittsburgh-based Alcoa, Inc., with his aluminum flexible-frame backpack, which featured a prototype pack designed, according to Trager family lore, by George Trager. With the new JanSport company, named for Pletz's partner/girlfriend Jan Lewis, the firm was wildly successful, winning its first of many design patents, for a daypack, in 1970.

By then times were really changing. Aluminum gear -- and new hiking guidebooks galore -- were flooding a market that supplied millions of the baby boom generation who were interested in gearing up for backcountry hiking. Yet even the Northwest's premier hiking-guide author and wilderness advocate, cantankerous Harvey Manning, took time to explain the upsides and downsides of owning a Trapper Nelson:

"The Trapper was dependable. The first aluminum-frame packs always busted in the field and then people were carrying them out in their arms. I took many years to convince because I knew the Trapper wasn't going to fall apart. It was just a wood frame with two horns; you put your toilet roll on one of 'em. Its advantage was the curved slats which molded it to your back. Your back rested against canvas ... [though] it really did punish your back. But I liked the simplicity" (Strickland).

Another advantage that Boy Scouts came to learn was that the thin steel rods (used to hold the detachable sack to the pack board) could be withdrawn while camping and used as skewers for roasting marshmallows over the campfire.

Always dependable and initially ahead of their time, Trapper Nelsons were certainly not perfect. Even The Seattle Daily Times' Don Duncan, who loved them, had to admit that they were "a quaint and archaic mode of transporting gear through the woods in this age of aluminum and magnesium frames and colorful miracle-fabric pack sacks ... By today's standards The Trapper is all wrong. It rides too high. Its sheet of canvas on the back causes excessive perspiration ... it is too heavy [three-plus pounds compared to a newer pack's two]" (Duncan, "Seattleite's ..."). Those concerns aside, Trapper Nelson packs had so impressed at least a couple consecutive generations of hikers that in 2013, almost three decades after their production was discontinued, there was still an active after-market for used specimens on eBay and other collectors' realms.

Meanwhile, upon John Hartsfield's retirement in 1995, John Tanner bought the 40-employee company and soon shifted its focus from making products for private-label retailers to pushing its own label -- and from outdoor gear to a wide array of items including daypacks, travel bags, messenger bags, and laptop computer cases.

Upstart companies, however, had eaten away at Trager's market share: by 2001 annual sales had fallen from about $20 million to $4 million. Many of those competitors were importing their products from overseas manufacturers and, said a contemporary news article, "Tanner's hoping the competition won't force him to follow suit. 'We're a dinosaur,' he admits" ("Trager Hopes ... ").

Still, Trager's products were highly regarded. In 2001, its 754B Courier Laptop Brief model "was named the top laptop bag in the country by Mobile Computing Online" ("Trager Hopes ... "). That same year, on February 28, 2001, the Nisqually earthquake wrecked many local buildings. Though the Trager USA factory sustained serious structural damage, the building remained until about 2007, when the city bought the property and condemned and bulldozed the building. (In 2013 it became the site of the launching pit for "Bertha," the tunnel-boring machine digging a tunnel to replace Seattle's Alaskan Way Viaduct.) Records at the office of Washington's Secretary of State indicate that the Trager Manufacturing Company, Inc., formally expired on September 30, 2004, and was recast as Trager USA, LLC, with a filing for incorporation on October 28, 2004. It appears that John Tanner relocated the company's administrative headquarters to Monroe and another facility to 18931 59th Avenue NE, Arlington, also in Snohomish County.