Glenn White -- like his father before him -- possessed a knack for deducing the mysteries of electricity and the material sciences. And advanced schooling allowed the polymath son to pursue an incredible number of often-overlapping hobbies and careers. Perhaps best remembered for his time as the 1960s soundman on the Seattle Center campus, or maybe as the popular 1970s University of Washington instructor or as proprietor of a pioneering Fremont fine-wine shop -- White was a rare example of a modern day "Renaissance man." The sheer range of the multilingual Mensa International member's myriad endeavors over the decades is mind boggling. A listing would include organ repairman, physicist, mathematician, Boeing guided-missile engineer and data analyst, experimental-music organization trustee, pipe organ and harpsichord designer/builder, audio engineer, radio station technician, university lecturer, Moog synthesizer instructor, cofounder of the Enological Society of the Pacific Northwest, sound-system designer, professional acoustician, lexicographer -- and lastly, in his later years, a Vespa-riding tech-applications engineer.

Like Father, Like Son

Glenn Dresie White was born on September 1, 1933, into a wheat-farming family in Lewis, Kansas. His similarly named father, Glenn D. White, set an admirable example by possessing a curious mind as well as a propensity for understanding technology. As a kid in the 1920s -- when every other farm was lit with kerosene lanterns -- the elder White electrified his family's farmhouse by putting a gasoline-powered generator in the basement and wiring it up. "It was the first one in that area and people would come for miles around to look at these electric lights" (Glenn White interview).

In 1920 Glenn D. built that state's very first radio station by putting a ham radio transmitter up in the attic and around 1925 built a silent motion-picture theater. Glenn D. White married Frances Dresie and her brother sent a letter from Oregon informing them that there were jobs available out there in the Northwest. The family, including daughter Marylyn and Glenn Jr., packed up and moved to Klamath Falls. Once there Glenn D. took a job as a refrigeration repairman, a gig he had no experience in whatsoever.

North to Seattle

In time Frances, looking for opportunities elsewhere, saw an ad in the Portland Oregonian for an oil-burner-repair job opening in Seattle with the Rossoe Furnace Company. Glenn D. got the gig and moved his young family into a tiny rental house on Queen Anne Avenue. One year later they were able to purchase a home at 2718 Nob Hill Avenue where they lived for several decades. Glenn D. also eventually purchased a modest industrial building at 318 N. 36th Street in the Fremont neighborhood, where he started a sheet-metal workshop doing work for heating companies.

As a teenage student around 1946, Glenn Dresie White took a keen interest in the fact that Seattle's first FM radio station, KRSC, was being installed in a building near Queen Anne High School. A few years later, KRSC expanded the operation and launched the region's first television station, which later morphed into KING-TV. White poked his head in, asked few bright questions, and quickly managed to befriend the chief engineer.

"I was interested in the audio, because the FM audio really sounded good, I mean, it sounded so much better than listening to a table-model radio. That was my first interest in audio: hearing that FM and learning about it, and listening to it over there. They had a nice broadcast-monitor system there: a Western Electric 12-inch speaker in a good infinite-baffle built into the wall" (Glenn White interview).

Meanwhile, White worked part-time at his father's furnace installation business. "I worked there during the summers when I was in high school. I did all the electrical stuff: wiring furnaces and thermostats and stuff. It was like kid's stuff" (Glenn White interview). Well, maybe so, considering that his skills were already advanced enough that beyond serving as the projectionist at school assemblies, he also built a Tesla coil device as a class project. White, a fan of classical music, also developed a fascination with pipe organs -- he read every book he could find on the topic and also visited local churches where he could listen to them.

On to College

"In 1951 I went to the University of Washington," White recalled, "and majored in physics because I felt that that was a basic science which I was interested in. I didn't care so much about engineering. That was applications, and I thought that's obvious if you know the science" (Glenn White interview).

As he once explained to The Seattle Times, "Physics is about the most basic of all the sciences; it encompasses acoustics and mechanics and the properties of the materials we use in building instruments" (Fisher). "I graduated in physics in 1955 and I specialized in acoustics ... but I was interested in, not so much physical acoustics as architectural acoustics and musical acoustics, how musical instruments worked and that kinda stuff" (Glenn White interview).

Old Pipe Organs

As a lad White had assisted an elderly family friend, Catherine Siderius, with her decrepit pipe organ. Later, she bought a 1912 Kimball pipe organ and he dutifully helped her dismantle, transport, and then reassemble it in her home. It was in 1954 that White learned there was an old waterlogged pipe organ for sale from a flooded theater in Chehalis. His father Glenn D. was also intrigued, and they bought it, packed it up (in seven separate vehicle loads), and then installed it in their basement. It took three years to repair and then The Seattle Times caught wind of all this and sent over a reporter -- and the famed photographer Josef Scaylea (1913-2004). A news article noted that already, at age 23, "White is a young man of many talents. ... Not only is he a physicist, carpenter, sheet-metal worker, electrician, musician, cabinet maker, and lathe-operator, but also ... a cement finisher" ("Missile Physicist ..."). Soon after, young White was running a little side business tuning pipe organs around town.

In 1957 White's passion for organs saw him flying to the Netherlands to attend the International Conference for Organ Builders. While there, he visited historic instruments -- particularly ancient harpsichords -- at various museums and then spent time in Kassel, Germany, where he studied pipe-organ design.

Meanwhile, White had also begun attending church at St. Mark's Cathedral on Seattle's Capitol Hill, where the scientist found spiritual comfort. It just so happened that the church's services also featured an organist backing the choir -- and a few excellent vocal solo vocalists, including a soprano named Janet S. Heller, to whom White would be married from 1960 to 1980.

Next Stop: Boeing

White first applied his new University of Washington physics degree by accepting a job at the Boeing Aircraft Company's Vibration Lab at the Plant 1 facility. He became a guided-missile engineer.

"Even though I never had any training in vibrations analysis, it's a lot like acoustics. So, it was not a problem for me. I had no problem figuring out the instrumentation and operating it ... I did fine, and I gradually worked my way up a little bit -- and when I left there I was in charge of Instrumentation and Data Analysis for the whole Environmental Test Lab. I built the first mechanical impedance measuring system, and the first Shock Spectrum Analyzer that Boeing ever had. I also designed a Phase Meter to measure the phase angle between two signals" (Glenn White interview).

Electromagnetic Recording

In the 1950s the rather new field of home recording with electromagnetic tape recorders intrigued many people. White's father bought a couple of well-worn Ampex 350 units from the Electricraft Hi-Fi store at 622 Union Street in downtown Seattle. Impressed that he was able to fine-tune them so easily, the shop hired him to do some of its repair work.

White Jr. soon fell into the small circle of pioneering audio engineers in Seattle, which included such characters as Boeing engineer Jim Hybeck, KFN radio announcer Jim Kuhnhausen, ACME studio operator Fred Rasmussen, and Seattle Harbor Tours owner Joe Boles. These were the type of guys who were always dragging their gear around to various theaters and ballrooms trying to record big-time touring musical stars so that they could then play their trophy tapes for their buddies. Among the shows that White himself captured was Andres Segovia at the Moore Theatre, and he and Boles once collaborated in recording the Seattle Symphony Orchestra at the Orpheum Theatre.

New Dimensions

One of several chapters of White's life that began in 1962 came when he met Joan Franks Williams (1930-2003), a New Yorker whose husband had just transferred to the Seattle area to accept a job at Boeing. Williams was an avant-garde composer with an interest in various forms of experimental music -- electronic music in particular. She became the director of an organization called New Dimensions in Music, to which White contributed as a technical advisor and trustee.

Over the next several years, New Dimensions presented cutting-edge public demonstration events and concerts that helped open the public mind to the merits of proto-electronica music. Perhaps the most impactful were the two programs that Williams and White conducted in July 1970 featuring the local public's first-ever exposure to a Buchla sound synthesizer, which had been invented in Berkeley, California, in 1963.

Before that Seattle debut, in 1967 White had presented an electronic production in the city titled "Watt's New." And in 1968, when Seattle composer (and organist at St. Mark's) Peter Hallock decided to revive a sixteenth century English morality play titled Everyman, White produced an elaborate six-track, four-channel stereo soundtrack "on tape using electronics and music written for the show" (Stockley).

Mixing Sound at Seattle Center

Meanwhile, also in 1962, ahead of the grand opening of Seattle's Century 21 World's Fair that April 21, local media was awash in advance coverage of every aspect of it -- including the design and construction of many of the notable buildings on the fairgrounds, which would become the Seattle Center campus after the fair closed that fall. White noted "that there was going to be a new, fancy, multi-channel sound system down there. I followed all that with bated breath," and then he read in The Seattle Times that there would be a job opening for a sound technician who would be in charge of all the sound equipment all across campus, including the Opera House, the Arena, the Coliseum, and the Food Circus, "and I thought, 'That would be an interesting job'" (Glenn White interview).

White applied, was interviewed by famed acoustician Paul Veneklasen and architect B. Marcus Priteca, and was successful. Hired just post-fair in 1963, White initially assisted with calibrating the Opera House sound system and then helped install a three-channel stereo system in the Arena, a system in the North Court rooms, and even one at the International Fountain -- a gig that also saw him programming a musical soundtrack that was synchronized with the water spouts. (Full disclosure: This writer, while serving as Senior Curator at the Experience Music Project museum, also scored that same gig for the museum's opening season in 2000.)

During his five years at Seattle Center, White mixed the audio for countless performances, including shows by the Seattle Symphony Orchestra and stars such as Bob Hope, Jack Benny, Jimmy Durante, Stan Kenton, Henry Mancini, the Smothers Brothers, and Ravi Shankar, as well as all the Ice Follies and Ice Capades programs. White also worked youth-market concerts, including those by Roy Orbison, the Beach Boys, Stevie Wonder, the Wailers, Paul Revere and the Raiders -- and one where Joan Baez brought along her harmonica player, Bob Dylan. But his most legendary night behind the soundboard was August 21, 1964, when White, with earplugs duly installed, worked with the Beatles as they performed before 14,000 frenzied fans at the Coliseum. White's reputation as the city's premier audio expert also saw him helping out various radio stations -- including KING-AM, KING-FM, KETO, and KLSN-FM -- with various technical issues over the years.

Record Production

White was also responsible for engineering the recording of numerous local discs. In 1964 he recorded the Seattle Symphony Orchestra's second album at the Opera House. In 1967 he cut its third -- and in 1975, its fourth, which when released in 1976 won kudos from The Seattle Times. The reviewer called the recording "an impressive achievement -- and an engaging music entertainment," and noted that as the recording engineer, Glenn White's "work is excellent. The orchestral sound is full, rich and balanced" (Johnson, "Symphony Has ...").

In 1971 White engineered an album by the Philadelphia String Quartet for Seattle's Olympic Records as well as its 1978 follow-up, which was cut live at the UW's Meany Hall in 1976 and 1977. White also recorded Seattle Youth Symphony concerts over a 20-year span and served as advisor during the Northwest Chamber Orchestra's 1981 sessions.

Olympic Organ Builders

White's expertise with pipe organs had won him a gig designing and scaling the pipes for a new organ that was installed at St. Paul's Episcopal Church at 5 W Roy Street on lower Queen Anne. Soon after, also in that year of 1962, he formed a casual partnership -- Olympic Organ Builders -- with Pacific Lutheran University (PLU) music professor and keyboardist David Dahl. Their goal was to sell imported pipe organs made in Germany by Werner Bosch, Detlef Kleuker, or Gebr. Späth Orgelbau. The plan was that they would custom design one to fit a particular space, the Germans would built it, and then White would oversee the installation.

Meanwhile, in 1963, White learned that the old Civic Ice Arena was going to be remodeled as the Arena (today's Mercer Arena) -- and that the venue's 1926 Wurlitzer pipe organ was about to be junked. He and his team salvaged it and placed it into storage. Then, between 1964 and 1965, they brought it back out and reinstalled it in the Seattle Center Food Circus building (later renamed Seattle Center Armory) and later used it during productions at the Opera House.

Later, in 1967, this activity all led to the formalizing Olympic Organ Builders as a business, one that added James Ludden as a partner and then moved into White Sr.'s old workshop in Fremont. Over time, at least 10 custom German-made organs were sold to Northwest churches, including Mountain View Lutheran (Puyallup), Messiah Lutheran (Spokane), First Lutheran (Richmond Beach), and John Knox Presbyterian (Burien) in Washington, and St. Mark's Cathedral (Portland), Lutheran Church (La Grande), and St. Bartholomew Episcopal (Beaverton) in Oregon, with another installed in the William Hurt residence in Seattle.

In time, Olympic Organ Builders began designing and building its own organs. These were installed in churches that included Pilgrim Lutheran (Puyallup), University Unitarian (Seattle), St. Stephens Episcopal (Longview), and St. Madeleine-Sophie (Bellevue), as well as at the University of Oregon in Eugene and Pacific Lutheran University in Tacoma. Others were shipped to Berlin, New Hampshire, and Dallas, Texas. The one built for David Dahl's own home was later transferred to Beautiful Savior Lutheran Church in Port Townsend. This commercial activity effectively ground to a halt around 1970, when Boeing faltered and the Seattle economy crashed.

But White continued to pick up solo work on occasion. He was retained as an installation advisor when Kirkland's St. John's Episcopal Church acquired a 1,000-plus-pipe 1892 Cole & Woodbury organ out of Massachusetts -- the oldest organ in the entire region. He also designed harpsichords -- in Italian, Flemish, German, English, and French styles -- that could be marketed as do-it-yourself kits. In addition, he built and sold about 15 completed harpsichords by 1981. Along the way, White also lovingly restored a 375-year-old Italian harpsichord.

Academia Beckons

In January 1968 -- a few months after White was accepted as a member of the high-IQ society Mensa International -- he began teaching a 10-week course on acoustics at the tiny New School for Music in Seattle's University District. Later that year William Bergsma, chairman of the University of Washington School of Music, contacted White wondering if he would be interested in joining the UW staff as Manager of Audio-Visual Engineering Services. Hired in 1969, White developed designs for, and oversaw the installation of, new sound systems for various campus facilities, including the new Kane Hall and the revamped old sports venue, Hec Edmundson Pavilion, on Montlake Boulevard, where the first concerts using the new equipment featured Simon and Garfunkel and the Grateful Dead.

Additional responsibilities were added, and White eventually advanced to recording various on-campus events and then joining the Systematic Musicology Department's faculty where he became a popular instructor teaching undergraduate and graduate courses in musical acoustics, laboratory instrumentation, recording technology, and research methods. He also set up UW's first-ever electronic-music course, utilizing a new Moog synthesizer.

It was while teaching a Recording and Reproduction of Music course that White saw the need for a resource that would explain numerous technical terms, a void that eventually he filled by authoring what is widely considered a definitive tome: The Audio Dictionary, published by the University of Washington Press. But White became frustrated during his 13 years at the school: "I never was able to convince Arts & Sciences to finance buying any equipment or building a studio on campus. We had a real nice place -- Room 35 in the basement of the Music Building -- it would be an ideal studio. They wouldn't let me do it. That's the reason I quit" in 1982 (Glenn White interview).

An Acoustical Consultant

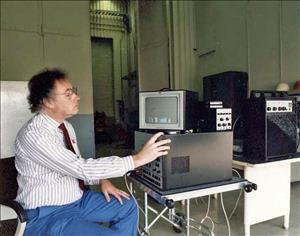

Well, that and the fact that in 1980 he'd accepted a tempting job offer from Bruel & Kjaer Instruments, a Danish company that built the highest-quality instrumentation for acoustic measurements, to work as a field applications engineer in the firm's Seattle office. White worked in the Seattle shop for 11 years before it closed. After that he worked for CSI Engineering and then for Bainbridge Island's DLI Engineering, from which he retired in 1998.

In demand as an acoustician, Glenn White also had a pragmatic ability to solve audio problems. One of the first Seattle recording studios he had helped design, back in 1965, was Kearney Barton's new Audio Recording Inc. at 2227 5th Avenue. It would prove to be a legendary facility where countless 1960s Northwest garage bands -- including the Kingsmen, the Wailers, and the Sonics -- benefited from White's custom-made mixing console and effective echo chambers.

White also served as an acoustical consultant for numerous theater projects across the nation, including at Princeton's Seminary Chapel, Vassar College, and the Roger L. Stevens Center in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Even back home his expertise remained in demand, and he took on jobs making interior renovations at Saint Mark's Cathedral in Seattle, designing a system at Tacoma's Rialto Theater, and consulting about what would be a new $120,000 state-of-the-art 24-channel sound system installed during the big 1980 remodel of Seattle's 5th Avenue Theatre.

A Fine-Wine Retail Pioneer

A busy guy with multiple careers, several businesses, and lots of hobbies, White wasn't quite done yet. Indeed, in 1976 he told The Seattle Times that he was always open to new opportunities: "If something interesting comes up, I might drop something I'm doing and go into that. It's hard to predict" (Fisher). And sure enough, White had also developed another passion: fine wine. In 1972 he and three friends opened the European Vine Shop in the basement of his Fremont workshop.

"We felt that the selection of wine wasn't what ... it should be in Seattle. We felt we could improve the availability of wines here, so we specialize in unusual wines not otherwise available in the state" (Fisher).

As one of Seattle's very first boutique wine shops, it quickly became a locus for oenophiles in the area -- even though it was only open about 12 hours per week. And it was those unusually short store hours that eventually caught the eye of Washington State Liquor Control Board inspectors, who assumed it was a front for importing wine mainly for the partners. They announced that the shop's Class F retail license would not be renewed. But then, when a hearing was held on July 31, 1978, to determine if the shop was even a legit business, 26 customers testified in person, adding further weight to the 200-plus letters of support already mailed in. The board sheepishly backed off. With all this publicity, the shop flourished and in the 1980s relocated to Capitol Hill, where it remained in 2016 as European Vine Selections Inc. at 522 15th Avenue E.

With his growing expertise in the wine realm, White figured it was about time that a new organization be formed to bring like-minded people together. Thus came about the Enological Society of the Pacific Northwest, which actually held its very first meetings around his dining room table. Then, in August 1975, White and other key members gathered to taste and rate some wines in what The Seattle Times described as a meeting that "may have been the first time a group of qualified judges sat down to taste virtually all Northwest table wines and then come up with a list of the very best" (Stockley, "Judges Pick Best ..."). Some of the other judges were later-well-known luminaries from the Northwest business and wine world: Weyerhaeuser vice president and vineyard owner C. Calvert Knudsen, attorney and vineyard owner Alec Bayless, vineyard owner Mike Wallace, and vineyard/winery owner Dick Adelsheim. (Among the winning wines were those by Seattle's Associated Vintners and Chateau Ste. Michelle.) And it just blossomed from there, with annual wine-judging events and then festivals. Today the organization remains active as the Seattle Wine Society.

In Addition

Glenn Dresie White also led a rich private life that included countless friends, colleagues -- and his beloved Carolyn, whom he married in 1981. Deeply smitten, White built her a beautiful harpsichord and took up gourmet cooking mainly in order to spoil her. The couple traveled widely (including to France, Italy, Denmark, and Mexico) and also hosted many "movie night" parties for friends in their basement home theater at 164 Ward Street, which he'd rigged up with twin 35 mm and 70 mm film projectors. Life was good.

But after such an extremely active and remarkable life marked by so many accomplishments and spiced with the joy of engaging in such a diverse array of personal and professional interests, Glenn White finally departed his family, colleagues, and friends -- escaping the snares of Lewy body disease -- on December 4, 2014. The UW's Glenn White Scholarship Fund in Physics was established and is maintained in his memory.