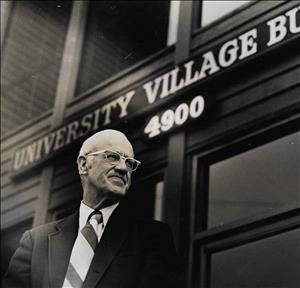

George H. "Mike" Allison, M.D., a Seattle psychiatrist who specialized in psychoanalysis, was a member of the original Northwest Clinic of Psychiatry and Neurology with Douglass Orr, M.D. (1905-1990), Edith Buxbaum (1902-1980), and Edward Heodemaker (1904-1969). Later he helped found the Blakeley Psychiatric Group in northeast Seattle. He was one of the first doctors to work at the Pinel Foundation Psychiatric Hospital (1948-1958), and one of a half-dozen psychoanalytic pioneers who helped build the Seattle Psychoanalytic Society and Institute, which in 1964 became a member of the American Psychoanalytic Association. He was a member of the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology, the American Board of Medical Specialties, and the Washington Association of Mental Health, among other medical associations. He served as president of the Seattle Psychoanalytic group in the mid-1970s while also participating in the activities of the American Psychoanalytic Association. He served as association president from 1990 to 1992 and helped break down the barriers that denied gays and non-medical analysts full access to membership. All the while he helped keep the Seattle psychoanalytic community together as it weathered the storms of two bankruptcies resulting from lawsuits by a psychotherapy student.

Family Life

George Howard Allison was born on May 24, 1921, to Robert (1883-1957) and Evelyn Offerman Allison (1888-?) of Yonkers, New York. He had four older siblings, Dorothy P. (1911-?), Robert C. (1912-?), Evelyn V. (1914-?) and Jean Marion (1918-?). Allison graduated from the University of Rochester in 1942 and from Yale Medical School in 1945. A year earlier, he had married Nancy Hart.

George Allison and Nancy Hart Allison had four children together. Son Thomas (1946-2012) was born at Camp Shoemaker Naval Hospital, California, on April 7, 1946; daughter Janet, son Anthony P. Allison (Tony), and Nick followed. The couple divorced in 1964. Three years later, in 1967, Allison married Joan Benefiel, a Seattle lawyer and family court judge. They had a son, Michael, born in 1968. Allison was also stepfather to Joan’s daughters. The couple was married for 48 years, until Allison’s death.

After Medical School

By the time Allison had completed medical school and his military duty, he had decided to specialize in psychoanalysis, a field of study that was increasingly -- since World War I -- used by the military to study psychiatric conditions of service personnel. He had served at California's Camp Shoemaker Naval Hospital, and had treated returning World War II veterans. This "stimulated his interest in problems of emotional trauma ..." (The Seattle Times, Obituary).

In 1946, Allison was one of 225 psychiatrists who worked with the National Research Council’s Committee on Veterans Medical Problems to study the relationship of military service to "mental breakdowns." During this period he read Freud's writings and was convinced that psychoanalysis held the key to unlocking conflicts within the psyche. Allison re-entered the navy during the Korean War and served as a psychiatrist at Camp Pendleton Naval Hospital in Oceanside, California.

The Menninger Clinic

The Menninger Clinic of Topeka, Kansas, offered Allison a fellowship in psychiatry. This was a plum position, since the Menninger Clinic was famous for infusing psychoanalytic theory into its psychiatric practice and vision. Here Allison worked with psychiatrists who would eventually settle in Seattle, including Douglass Orr, M.D., the father of Seattle psychoanalysis. Orr, like Allison, focused a good part of his medical practice on the study of war neuroses.

Speaking to the 2009 Seattle Psychoanalytic Society and Institute graduating class about his love for psychoanalysis, Allison told the audience:

"Nothing could match the excitement of Topeka with the colorful, prominent leaders there — such as Karl Menninger, David Rappaport, Robert Knight, Merton Gill, and others .... The overwhelming excitement of the large residency (100), all of whom were enthused and dedicated to the new field, spurred me on. The downside was that studying psychoanalysis created a strong need to be analyzed and there were a limited number of openings with the graduate analysts in Topeka. This led, in my case, to accepting the offer by the Northwest Clinic (newly formed then) to work for the attractive salary (at that time) of $500 per month — plus a chance to begin analytic training and start analysis" ("SPSI Graduation Talk").

Moving to Seattle

In 1948, after completing his residency, Allison and his young family -- Nancy and the children -- moved from Kansas to Seattle. Allison joined Douglass Orr and Edith Buxbaum in their group practice at the Northwest Clinic. One of his first assignments was to assist staff and manage patients at the newly formed Pinel Foundation Psychiatric Hospital, which operated from 1948 to 1958 at 2318 Ballinger Way in Lake Forest Park, located at the north end of Lake Washington.

Meanwhile his own psychoanalytic education continued. This included a personal and training analysis, at least one of which was necessary for acceptance into the American Psychoanalytic Association. From approximately 1949 to 1951, Allison entered into an analysis with his mentor and colleague, Douglass Orr. Less than a decade later he would take a second analysis with Edith Buxbaum, also a mentor and colleague. In some ways, Allison explained to this writer in a 1994 interview, the analysis with Orr represented a paternal transference while the analysis with Buxbaum represented a maternal transference. (Transference is the redirection of emotions, usually felt in childhood, toward a substitute, such as the analyst.)

This was a difficult situation for all involved, since classical analysts hold that the best analysis is one in which analyst and analysand have little or no outside contact with each other. Everything that occurs between them must take place within the context of the 50-minute hour and in the setting of the therapeutic environment -- the therapy room. What happens outside that environment could conceivably impact what goes on between the two parties -- analyst and analysand -- in the next hour of treatment, or in following sessions. Analysands must feel free to discuss intense feelings that may concern people within their families, work places, educational, or entertainment environments. Analyst and analysand must inhabit a "clean" environment without the eyes of others impinging on the creative process that takes place within the context of the 50-minute hour. This, of course, is in theory. In reality, it is difficult to adhere to such strict rules. Especially in early psychoanalytic Seattle, where colleagues were each other's students, analysands, and analysts.

In Seattle this ideal was not possible since there were only two training analysts available, Orr and Buxbaum. But the close-knit situation did give rise to greater self-understanding, Allison said. He had worshipped his father and transferred those feelings onto Orr. When the elder Allison died in 1957, the son would enter into an analysis with Edith Buxbaum and could "use" her as a mother figure; as such, Allison said that he learned more about his relationship to his mother in her widowhood.

In 1959, Allison became a member of the American Psychoanalytic Association and was intimately involved with that organization for the rest of his life, bringing a Northwest presence to the national psychoanalytic scene. He served on, or chaired, numerous committees including History and Archives, Psychoanalytic Education (two four-year terms), Psychoanalytic Research, and the Committee on Psychoanalytic Ethics. In addition, in the early 1980s, the association's Executive Council sought him out to be a member of its Exploratory Nominating Committee, as well as the Special Ad Hoc Committee of the Board of Professional Standards. From 1990 to 1992, he served as its president. He loved the work, and also, as he said in 1994, working for the American gave him an excuse to return to Yonkers, his hometown, where some of his friends and relatives still lived.

Life Outside Work

Allison enjoyed sports and travel; and he had a friendly and far-reaching personality. From his obituary:

"Mike's sporting pursuits included skiing, sailing, basketball, and squash. Well into his 80s he was bicycling to work and competing with — and often beating — family members on the tennis court. He also loved to travel with Jo and other family members; Mike had memorable journeys around the US and to Europe, Russia, the Middle East, South America, and Japan, with overseas trips often built around meetings of the International Psychoanalytic Association" ("George H. 'Mike' Allison MD," [obituary]).

From the time Allison moved to Seattle, he was involved politically, professionally, and socially in a variety of civic organizations and causes. His speaking engagements included the University Grandmothers' Club and topics ranged from weight control to various aspects of mental health. He was a trustee of the Psychiatric Clinic at 411 Fairview Avenue N. He voted for public school levies, was a patron of the Seattle Symphony, and served on a committee to find a new stadium site.

He was a member of the Reginald Parson’s Guild, along with Douglass Orr, Edward Hoedemaker, Robert Worthington (1907-1990), and other psychiatrists in town. (Reginal Parsons was a founder of Pinel Foundation Hospital). For the 1964 presidential election, Allison helped organize the Washington State Scientists, Engineers and Physicians for the Lyndon Johnson/Hubert Humphrey ticket. In 2008, along with thousands of doctors throughout the country, Allison affiliated with Doctors for Obama ’08 by supporting the Obama Health Care Plan.

In Defense of Freud

Since the beginning of psychoanalysis in the late nineteenth century, professionals and non-professionals alike have been throwing darts at Freud; no doubt the Freud Wars will continue. Nonetheless, Allison was a staunch believer in Freud. In 1993, having just completed his role as president of the American Psychoanalytic Association, he told a reporter for Time:

"... Freud's influence in mental health as well as the humanities is much greater than it was 40 years ago. I hear much more being written and said about Freud .... There are now more than 200 talking cures competing in the U.S. mental health marketplace, and 10 to 15 million Americans doing some kind of talking ... they really are based on Freudian principals, even though a lot of people who head these movements are anti-Freudian officially. But they are standing on the shoulders of a genius" ("The Assault on Freud").

Cherishing an Identity

Allison’s continued enthusiasm for psychoanalysis was underscored in his 2009 talk to the graduates of Seattle Psychoanalytic Society and Institute. He was 88 years old and had been a practicing psychiatrist all of his adult life and most of it as an analyst. Here he speaks of his psychoanalytic identity:

"I cherish mine, and encourage you to cherish yours. Wear it proudly, and enjoy the advantages we have as psychoanalysts. We are privileged to be analysts and to be able to engage in this wonderful work. It is unlike any other, with the intense intimacy we experience with our patients and with ourselves — analyzing them and ourselves over our professional lifetimes. We are truly blessed, I believe. In closing, I want to again mention the American Psychoanalytic Association as well as other organizations which offer fertile ground for post graduate development and growth. I urge you to dedicate yourself to seek such further growth and development — and thereby feed your own excitement and enthusiasm. Your intense involvement as a psychoanalyst with similar dedicated enthusiasm, will surely be rewarded, as mine has been" ("SPSI Graduation Talk," June 12, 2009).

Allison practiced psychoanalysis in Seattle until he was 91 years old. He retired reluctantly.

Changing Times

But by this time, the traditional practice of psychoanalysis -- 50 minute sessions on the couch four or five days a week -- had changed from its nineteenth-century beginnings in Vienna and Berlin, and even from its twentieth-century beginnings in the United States, where it spread from New York to Seattle to what some would call a "watered-down" therapeutic process.

For Allison and other devotees of a "pure" analysis -- one that is undertaken four or five days a week, where the analysand/client/patient lies on a couch for sometimes three, four, five or more years attempting to get to the heart of his or her life-long conflicts -- theoretical explanations often ignore the cost factor. Not that the cost factor is beside the point: Analysts are aware that insurance companies do not pay for long-term therapies and only those clients of robust financial means can afford to lie on a couch and talk away their problems. Alternative-to-psychoanalytic therapeutic methods such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (focus on thought patterns and behavior) or relational therapy (focus on relationships with others) are often more attractive to the client because they are less expensive than psychoanalysis and are often paid for, at least in part, by insurance companies. Even though psychoanalytic institutes often establish low-income programs for a limited number of patients, it is difficult to get accepted into such programs; moreover, senior-level analysts are preferred to cover this end of the psychoanalytic business and are not always available.

Allison refers to alternative therapies as "homogenized psychoanalysis." Dictionaries define homogenized as "blending unlike elements." For Allison, unlike elements may refer to various modes of therapeutic interpretation. In a 1994 essay for instance, he explains that the psychoanalytic process "typically requires thorough immersion through frequent sessions which permits greater resolution of the transference or transference neurosis." He suggests that frequency of visits allows for "insight and greater opportunity for the achievement of autonomy." He concedes that "Other modes of therapeutic action also play into the process as in psychotherapy, but the interpretive mode with progressive insight distinguishes psychoanalysis proper" ("On the Homogenization of Psychoanalysis and Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy")

In other words, interpretations regarding emotional health depend upon resolution of the transference neurosis, that is, differentiating one's mother, father, sister, brother, even a cousin, from the likes of the therapist.

In a later paper, "The Shortage of Psychoanalytic Patients: An Inquiry into Its Causes and Consequences," Allison worries that the shortage of psychoanalytic patients will effect just how psychoanalysis will be taught within psychoanalytic training programs. What will the curriculum look like? How will institutional policies be developed? He worries that the variety of theoretical interpretations comes at a time when psychoanalysis proper is losing patients and that different types of therapies will conflate upon each other so that psychoanalysis will no longer be recognized in its pure form. He does not mention in this essay that not everyone who reaches out to a therapist is interested in resolving the so-called transference neurosis or even believes it exists!

Allison admits that "mainstream medical psychoanalysis, which dominated the field in the United States well into the post–World War II era, is often seen to have maintained a rigid dogmatic theoretical orthodoxy in its training institutes, as well as a stultifying exclusionary elitist stance toward the rest of the scientific world. Many see this as having been self-defeating,” he writes. But "[s]ome have argued that psychoanalysis is now experiencing something of a renaissance in contemporary culture because of the proliferation of new perspectives ... that many suggest may more inclusively address the complexities of social and psychological life" ("The Shortage of Psychoanalytic Patients...").

No doubt the homogenization of psychoanalysis and various types of psychotherapies will allow for more inclusivity than conventional psychoanalytic institutes ever dreamed possible. Dr. Allison would be proud of this newness. He was aware of the elitism inherent in psychoanalysis, all the while he loved the process. The societal ramifications for change in the field of psychoanalysis are far-reaching: Psychoanalysis has always comprised a predominately white group of healers, whether in Europe; Topeka, Kansas; Chicago; or Seattle. Little has changed in this regard in terms of clients or practitioners during its hundred-plus years of development.

But in today’s twenty-first century that demographic is already changing; and people of color, especially those coming through the fields of social work and psychology, will push the barriers, just as lay analysts did (and won) a few decades ago. And just as gay doctors pushed through. People of color will push through those barriers too -- in Seattle and beyond. And this writer believes that George "Mike" Allison will be smiling.

George Allison died from heart disease on March 19, 2016. On Saturday, May 21, 2016, at 11 a.m., a memorial service was held for him at the Center for Urban Horticulture in Seattle's Laurelhurst neighborhood, adjacent to the University of Washington, where Allison had been a clinical professor in the Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences Department.