The West Cashmere Bridge was built in 1929 across the Wenatchee River about a third of a mile west of the city limits of Cashmere in Chelan County. Cashmere lies entirely on the south side of the river and has long been the center of processing and shipping for nearby orchards and farms, including those north of the river. The West Cashmere span, known locally as the Goodwin Bridge, carried Goodwin Road northwest from its intersection with the Sunset Highway, then crossed railroad tracks and the river via a series of connected spans of three different designs. On the north side Goodwin Road turned west, then looped around and back to cross under the bridge's approach ramp and intersect at a crossing with U.S. 2 and Hay Canyon Road. For many decades the bridge served the transportation needs of growers, processors, shippers, and the public, but by the second decade of the twenty-first century it had far outlived its useful life, was open only to restricted traffic, and was slated for removal and replacement.

The Lay of the Land

The Wenatchee River starts at Lake Wenatchee and winds a serpentine 53-mile course (slightly more than 30 miles as the crow flies) south and east to its confluence with the Columbia River. Among towns and cities it passes are Leavenworth, Peshastin, Dryden, Cashmere, and Wenatchee, the Chelan County seat. Along its length the river is crossed by eight bridges for vehicular traffic, of which the West Cashmere Bridge is one.

Much of Cashmere's commercial activity involves growing, processing, and shipping fruit, primarily apples and pears. Bordering the city in all directions are orchards, made possible by irrigation projects that first brought irrigation water to the valley in 1901 through the Peshastin Ditch, a laborious excavation that began in 1889. It eventually became part of an extensive Wenatchee Valley system, including the Shotwell Ditch and the much larger Highline Canal, irrigating thousands of acres of land stretching from Dryden down to Wenatchee.

The city of Cashmere lies entirely on the south side of the Wenatchee River. Just beyond the city's western boundary, Chelan County designated an Urban Growth Area. A sizeable portion near the West Cashmere Bridge was zoned for commercial and light industrial use. Nearby, just within the western city limits, plans were underway in 2018 for a new industrial park on an abandoned mill site. The West Cashmere Bridge had for some years been too narrow and structurally compromised to safely handle the trucks that such uses require, forcing them to be rerouted through the main business section of Cashmere or on a nine-mile detour west to where U.S. 2 crosses the river at Dryden.

Mission to Cashmere

Where Cashmere now stands a band of the Wenatchi Indian Tribe long had a winter village called Ntuatckam along the Wenatchee River. In 1850 the village's seasonal population numbered about 400, sustained by ample fish, game, and edible plants.

The region was visited by non-Indian trappers and explorers since early in the nineteenth century, but not until 1863 did an Oblate priest, remembered only as Father Respari, come to stay. He built a one-room log mission beside a small tributary of the Wenatchee River, now called Mission Creek, ministering to and seeking converts among the indigenous population. After about 20 years he was succeeded by Father Urban Grassi (d. 1890), a Jesuit. It is uncertain exactly when he arrived -- most sources say he came to the valley in 1883, but in that same year he is recorded as supervising construction of Gonzaga's original college building in Spokane, 150 miles east. When he did arrive, Father Grassi built a log church next to the Wenatchee River, and the surrounding area became known as Mission.

In 1881 Mission's first permanent non-Native settler, Alexander Brender (1851-1940), squatted on land in what is still called Brender Canyon. In subsequent years a town slowly began to form about a quarter mile west of Father Grassi's Mission, which the newcomers, perhaps too busy to exercise much imagination, named New Mission, thereafter referring to Father Grassi's compound as Old Mission. In 1889 a Mission post office was established.

In 1892 the Great Northern Railway reached Mission and the town's first plat was recorded. The population grew slowly, in part because trains would not make regular stops there until 1903. When residents voted to incorporate the town in July 1904, it was noted that there were several other communities called "Mission" scattered around the Northwest. At the suggestion of Judge James Harvey Chase (1831-1928), the name was changed to Cashmere, an inspired if misspelled evocation of the beautiful and fertile Vale of Kashmir in faraway India. By that time there was a railroad depot, several stores, a variety of tradespeople, at least one hotel, and many of the other businesses and amenities that make a town a town. One thing Cashmere did not have, however, was a bridge spanning the Wenatchee River, on whose opposite side orchards and farms were starting to flourish.

The First Bridge

In 1903 a petition was submitted to the Chelan County commissioners by people living just west of what was still called Mission, although the organizer of the effort hailed from the other side of the Wenatchee River. He was Milton Orlando Tibbets (1861-1909), a native of Ontario, Canada, who earlier had purchased several tracts, put in irrigation, and developed a substantial farm and orchard operation north of the river. The petition asked that a road be built north of Mission that would intersect with the existing main road and carry traffic northwest about 1,000 feet to a yet-to-be-built bridge. This would benefit many, but Tibbets in particular, who needed a better way than boats to get his crops across the river to where they could be shipped by rail to points west and east.

The road was approved and early in 1904 Tibbets spearheaded a second petition, asking the commissioners to authorize "a bridge to be built across the Wenatchee River, about one and one half (1 1/2) miles above Mission" ("Tibbets Bridge"). He offered to put up $800 toward the cost, and on February 3, 1904, the commissioners voted to fund the remainder. They directed the county surveyor to locate a good site before the next board meeting, scheduled for the coming April.

On April 7, 1904, the commissioners invited bids for a bridge to be located "about one mile west of the town of Mission" ("Tibbets Bridge"). Modern maps indicate that access to the span was via what is now a dead end called Hagman Road, although that is most likely not its original name. This road intersected with the Great Northern tracks at a ground-level crossing about 700 feet inland.

A contract was signed with I. J. Bailey and Company on May 25, 1904, "to construct, build and complete a wagon bridge over and across the Wenatchee River ... to be completed on or before the first day of September, 1904" ("Tibbets Bridge"). Two sections, one measuring 160 feet and one measuring 120 feet, would meet near mid-river, where their ends rested on two side-by-side concrete-filled steel cylinders embedded in the river bottom. The lowest point of the completed span was required to be at least "7 feet above the extreme high-water mark of the Wenatchee River" ("Tibbets Bridge").

The Tibbets Bridge, of a type called a Howe truss, was finished without incident, but three years later it became clear that someone had underestimated just how high the extreme high-water mark of the river could reach. In 1907, a year of heavy rains, the commissioners feared the span was in imminent danger of being washed out: "[O]wing to the time of year and other causes it appears to the Board that an emergency exists for the repair and raising of said bridge" ("Tibbets Bridge"). On April 22, I. J. Bailey and Company agreed to raise the entire span by three feet for a modest $410. The work was completed within a month.

The Tibbets Bridge, designed and built to carry wagons, served its immediate purpose, but the coming onslaught of motorized vehicles guaranteed that it would have a relatively short useful life. Its replacement, the West Cashmere Bridge, would come 25 years later, in 1929.

The West Cashmere Bridge

It is unclear whether the Tibbets Bridge was still in use when planning began in 1927 or 1928 for its replacement. There are some indications that it may have been severely damaged by floods in 1925. It is known that in May 1928 Chelan County hired Henry A. Hagman (1883-1964), the eventual builder of the West Cashmere Bridge, to remove the Tibbets Bridge (or its remnants) and salvage the materials.

Approximately 700 feet west of the Tibbets span a new street, called Goodwin Road, was built that intersected with the Sunset Highway about 850 feet to the southeast. Goodwin Road would lead to and across the West Cashmere Bridge, giving the farms and orchards on the Wenatchee River's north bank greatly improved access to Cashmere, where their products could be shipped both east and west, by highway or railroad.

The Designer: Maury M. Caldwell

The West Cashmere Bridge was designed by Maury M. Caldwell (1875-1942), a consulting civil engineer specializing in concrete and steel structures, with his office in Seattle. Caldwell, a native of Virginia, was experienced in bridge design, having worked for the C. G. Huber Company, the Union Bridge Company, and the Strauss Bascule Bridge Company. He is believed to have arrived in the Northwest in 1904 and was hired as a draftsman by the Tacoma City Engineering Department. In 1910 he was a named partner in an engineering firm, but soon returned to government employment, and in 1914 was the chief deputy engineer for Pierce County.

By 1916 Caldwell had returned to private practice, and while there is no record of him ever being licensed as a professional engineer in Washington, his expertise seems not to have been in question. Among the bridges that he is known to have designed before the Cashmere span were the Burnett Bridge over South Prairie Creek in Pierce County (1920); the Pasco-Kennewick Bridge, the first of three cantilever bridges built across the Columbia River in the 1920s (1922); and the Meridian Street Bridge across the Puyallup River in east Pierce County (1925). In 1921 Caldwell supervised construction of, and may have played a role in designing, the James O'Farrell Bridge in eastern Pierce County on SR 165, a spectacular deck-arch span that crosses high over the Carbon River. It appears that the last bridge he designed in Washington was the Granite Falls Bridge over the South Fork Stillaguamish River, in 1934. He was working to develop a gold-mining claim in Cottonwood, British Columbia, when he died there in 1942.

The Builder: Henry A. Hagman

The contract to build the West Cashmere Bridge was awarded to Hagman, a Minnesota native, son of Swedish immigrants, and very much a self-made man. In 1900, at the age of 16, he was working as a farm laborer in his home state, where he lived until at least 1905. By 1915 Hagman was living in Tacoma, and his occupation that year was given as "foreman" (1915 Tacoma Polk's), although his employer was unidentified.

Hagman then disappears from the public record until 1919, when he lived in Seattle and listed his occupation as engineer. In 1922 he was working as a foreman for the Washington Machine & Storage Company, and in 1925 was described as a "hoisting engineer" (1925 Seattle Polk's), a specialist in the setting up and operation of cranes, derricks, and other lifting devices. The following year he described himself as a "contractor" (1926 Seattle Polk's).

Henry Hagman was still living in Seattle in 1928 when he won the contract to remove the Tibbets Bridge and, shortly after, the contract to build the West Cashmere Bridge. The latter was signed on September 18, 1928, and specified a completion date of May 1, 1929. Hagman moved to Chelan County and remained in Eastern Washington until his death in Spokane 35 years later.

From available evidence, the West Cashmere Bridge was the first that Hagman built, but it would not be the last. At least four others were credited to him between 1931 and 1955 -- the Monitor Bridge, a graceful 357-foot concrete-arch bridge that spans the Wenatchee River at Monitor, downstream from Cashmere (1931); the steel Grande Ronde River Bridge in Asotin County on SR 129 (1941); the Long Lake Dam Bridge in Stevens County, a concrete arch bridge over the Spokane River on SR 231 (1949); and the Greene Street Bridge in the city of Spokane (1955). All remained in service in 2018.

Design Phase

The Sunset Highway, the first reasonably usable vehicular road over the Cascade Mountains, was dedicated in 1915. It ran through downtown Cashmere, connected to Seattle via Blewett Pass and Snoqualmie Pass, and ran east to Wenatchee and Spokane. Just west of Cashmere's city limits at the site of the proposed bridge, the Great Northern had one set of tracks, which ran very close to the river's south bank. Both the railroad and the county wanted to have a grade-separated (elevated) crossing there to avoid the delays and dangers occasioned by the ground-level intersection on the road leading to the Tibbets Bridge.

The design had to be finalized before the call for bids went out, and this fell to Caldwell, working in concert with John D. Duff Sr. (1888-1962) , Chelan County's chief engineer, who would supervise the project. Due in large part to the demands of the Great Northern Railway, the process proved challenging, and the final design called for an unusual combination of eight different sections of three distinct designs.

One problem was that the railroad insisted that the approach to the bridge be elevated to pass over a second, and perhaps even a third, set of tracks (as of 2018, neither had been built). A thornier issue, and one that apparently didn't come up until the initial design was completed, was the railroad's insistence that it needed 27 feet of clearance between the tracks and the lowest point of the overpass. From what correspondence exists, a level of frustration on the part of the county engineer is evident. On May 28, 1928, Duff wrote to Caldwell:

"All our controversy with the Great Northern Railway Company, concerning the Cashmere West Bridge, has availed us nothing; they will not change their attitude and insist on 27 foot clearance above the track ... This state of affairs, no doubt, calls for a change in the plans of the bridge" (Duff letter).

Exactly one month later Caldwell responded:

"I wish to advise you that I am revising the plans for the Cashmere West to provide the twenty seven foot clearance required by the Great Northern R.R. and would like you to confirm my opinion that this is from the base of rail as is usual" (Caldwell letter).

Two days later, Caldwell sent sketches of the revised plan to Duff that were accepted by the county and the railroad. The plans were provided to interested contractors, and Henry Hagman submitted the winning low bid of $52,203. Other bids ranged from $53,362 to a high of $77,266.

Reaching the River

The West Cashmere Bridge is of historic significance because of the role it played during the middle decades of the twentieth century in support of Cashmere's agricultural operations, and for the designs used for its various components, particularly the steel truss sections that spanned the river.

Because it needed to provide clearance not only for the existing railroad tracks, but for additional tracks that might later be added, the southern approach to the bridge had to begin its incline about 150 feet from the Wenatchee River's south bank. The first section of the approach was a 34.5-foot reinforced-concrete girder span. This is basically a concrete roadway supported by concrete girders resting on concrete piers resting on concrete pads, all of which are strengthened with embedded steel reinforcement. On either side of the roadway was a concrete balustrade with arch-shaped openings along its length, giving drivers some view of the surrounding terrain.

The next section of the bridge, 82 feet long, would carry traffic over the never-built second set of railroad tracks. Its design was one rarely used in highway bridges -- a steel riveted plate-girder through span, a complicated name for a relatively simple structure.

I-beam girders, named for their shape in cross-section, can be formed from one piece of steel by rolling it through dies, or fabricated from separate steel plates that are welded, bolted, or (in this case) riveted together. The horizontal top and bottom elements of an I-beam are called flanges; the vertical piece connecting them is called the web.

The driving surface of a girder bridge is most commonly borne by the top flanges, but in a "through span" girder bridge the roadway is supported by the inner bottom flanges. The primary benefit of this method is that it maximizes clearance above the ground (or water), since there is no supporting structure extending beneath the girder's bottom flanges. One drawback is that the vertical webs and top flanges on either side form solid steel walls, or parapets, which block visibility from the roadway. Another problem is that the entire structure can be weakened if those parapets are struck by particularly heavy or wide vehicles. The third and perhaps most critical problem is the virtual impossibility of widening the roadway on such a span. Due to these factors, through-girder bridges are most commonly used to carry railroad tracks and not vehicular traffic.

Before the West Cashmere Bridge actually reached the south bank of the river there was yet a third section, crossing the existing railroad tracks and maintaining the 27-foot clearance demanded by the Great Northern. It was another reinforced-concrete girder span, nearly identical to, but at 40 feet somewhat longer than, the one at the other end of the through-girder section. On the north side of the river, three connected concrete girder sections, each about 35 feet long, carried traffic on and off the bridge. The balustrades here splayed gracefully outward at the north entry point to deflect wayward vehicles, a method used before the invention of more-advanced barriers. In later years steel guardrails were added.

Crossing the River

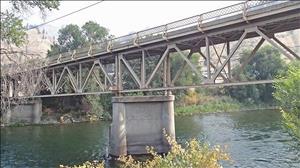

The West Cashmere Bridge crossed the Wenatchee River on two 117-foot riveted steel deck-truss segments, an unusual choice adding to the span's historical and engineering interest. The pattern of this bridge's supporting members identifies it as a Warren truss, a design first patented in England in the mid-nineteenth century. The two deck trusses rested on concrete piers on each river bank and met on a dumbbell-shaped, reinforced-concrete pier at mid-river. The concrete bases for the piers on the north bank and in mid-river were designed to rest on wooden piles, but some reports indicate they were grounded on bedrock "about twelve feet below the river bed" ("$52,000 Span Is Completed"). Because of the elevation on the south end needed to clear the railroad tracks, the deck trusses sloped downward across the river from south to north.

The supporting frameworks of a steel truss bridge form a series of interconnected triangles that distribute the forces to which the span is subjected -- tension, compression, torsion, and shear. There are three basic truss variations -- through truss, pony truss, and deck truss. The vertical sides of a through-truss bridge rise above the roadway on either side and are connected at the top by a webbing of transverse steel cross-members, which adds strength but limits vertical clearance. Bridges without this cross-bracing are called pony trusses. They have no clearance limitations, but are less robust under heavy loads.

On a deck-truss bridge, the supporting framework extends below, rather than above, the roadway. A pure Warren truss comprises a series of steel members that form equilateral triangles on either side of a bridge along its length. For additional strength, vertical support members can be added between the apex and the center of the base of the triangles, which was done with the West Cashmere span in an alternating pattern.

Along the length of the roadway on both sides were 42-inch-high steel bridge rails with a diamond-shaped lattice pattern, strengthened with angled steel supports attached to the top beam of the deck truss. While a number of Warren pony- and through-truss bridges can still be found in Washington, few that were built before the 1930s have endured, and surviving Warren deck-truss spans like the West Cashmere Bridge are even scarcer.

Completion of the West Cashmere Bridge was somewhat behind schedule due to the railroad's demands, but well in time for the harvesting of the valley's 1929 fruit crop. Each successive season was producing larger yields, particularly of apples, and there was no lack of willing buyers in Seattle and in Spokane and points farther east. The final shipment of apples from the 1928 crop of the Cashmere Valley left the city by rail in mid-May 1929. It was the largest crop produced in the valley up to that time and filled 2,441 railcars, an increase of 859 over the 1927 season. A Seattle news article noted, "The shipment of apples to go out today consists of Winesaps, all in excellent condition through cold storage" ("Last of Largest ..."). In addition to fresh apples, the Cashmere Valley shipped out 194 train-car loads of pears, and 13 of dried apples produced by a local dehydrating factory.

A New West Cashmere Bridge

The original West Cashmere Bridge was built to accommodate the trucks and automobiles of its era, most of which were both smaller and considerably lighter than those of later years. After long years of service, by early in the twenty-first century the span was too narrow, increasingly unsound, and deficient in multiple ways. The Chelan County Public Works Department summarized the findings of a 2012 study:

"[T]he ... fracture-critical bridge is both functionally obsolete and structurally deficient. It is currently posted for both weight and height restrictions ... To address these deficiencies requires the investment of millions of dollars ... simply to increase the longevity of this functionally obsolete bridge ... Other deficient elements of this bridge include crumbling bridge railing, spalling concrete deck, scoured bridge piers, inadequate ... bridge width, and overall clearance constraints" ("... 2017 Tiger Grant Application").

By 2018, after a lengthy design process that began in June 2015, plans for a replacement were well along. The proposed new span would be in the same place as the existing bridge, but on the north side it would be elevated to pass over U.S. 2 and would exit onto Hay Canyon Road. Construction was scheduled to begin in 2020, at a projected cost of $23.5 million.

A Second Life?

Because of their historic significance, Chelan County officials hoped that the two Warren-truss sections of the West Cashmere Bridge could be saved. Although offered "for sale," the county planned to donate them to "any governmental, non-profit or responsible private entity for public or private use" ("West Cashmere Bridge for Sale").

Interested parties were required to agree to assume legal and financial responsibility for the spans and to maintain the features that give them historic significance and continued eligibility for the National Register of Historic Places. The county would pay a maximum of $110,000 toward the cost of dismantling the steel trusses, but the new owner would bear the cost of removal from the site, transportation to a new location, and reassembly. The offer was to remain open until January 2019.