Jimi Hendrix -- the single most famous musician to ever emerge from the Pacific Northwest’s music scene -- rose from extremely humble beginnings to establish himself as perhaps the most gifted and inventive guitarist of all time, one who would be globally recognized as a major force in twentieth-century music. Born and raised in Seattle, Hendrix absorbed the region's distinct rockin' R&B aesthetic of the "Louie Louie" era, learned to play guitar, and performed in a series of at least three teenaged dance combos between 1959 and 1961. After a couple minor brushes with the law, Hendrix joined the U.S. Army in 1961, and upon discharge in 1962 formed an R&B band in Nashville, and then toured the "chitlin' circuit" of African-American-oriented nightclubs. By 1964 Hendrix had made his way to New York where he was discovered by elite British rockers. Flown to London in September 1966, his new band, the Jimi Hendrix Experience, was a literal over-night sensation. In 1967 they slayed the Monterey Pop Festival’s crowds, within months became a top concert draw, and their albums were instant psychedelic rock 'n' roll classics. In 1969 Hendrix headlined the legendary Woodstock festival. In 1970 the magnificent young musician died in his sleep.

A Family of Entertainers

The Hendrix family first arrived in the Pacific Northwest during the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition of 1909. Nora (nee Moore) Rose Hendrix (1883-1984) was a dancer with Lacy’s Band and their traveling vaudeville troupe whose “The Great Dixieland Spectacle” show was featured at the expo’s Dixieland pavilion. Her husband, Bertran Philander Ross Hendrix (1866-1934), was a stagehand/roadie for the organization. Family legend tells that after the exposition concluded in October 1909, the troupe was stranded without future bookings and disbanded.

By 1912 the couple had settled into Vancouver, B.C., and the following year brought them their first child, Leon Marshall Hendrix. Subsequent years brought additional offspring including James Allen Hendrix (1919-2002), who developed a love of competitive dancing by the 1930s. It was while attending a Fats Waller dance one night that Al, as he was called, met the pretty 16-year-old from the mining town of Roslyn, Washington -- Lucille Jeter (1925-1958) -- who would become his wife in 1942. Months later, on November 27, 1942, she bore their first child, Johnny Allen Hendrix, at Seattle’s King County Hospital -- today’s Harborview Medical Center (325 9th Avenue).

By that time Al was stationed overseas with the U.S. Army, and he was not pleased with the name Lucille had bestowed upon their son. Young Lucille loved the nightlife and partying and in time Al would learn that she had not been entirely faithful to him -- with one probable partner in adultery being a fellow named Johnny Williams. Upon his return from service, Al legally renamed his son James Marshall Hendrix (in 1946).

West Coast Seattle Boy

By 1947 the Hendrix family was settled into a unit of Seattle’s Rainier Vista Housing Project, but their domestic home-life never really did settle down. Al and Lucille bickered and battled over her drinking and disappearing for days at a time as young Jimmy began attending kindergarten at Rainier Vista School (3100 Alaska Street S). Meanwhile Al was totally surprised when Lucille gave birth to another boy, Leon Morris Hendrix, in January 1948. Other children -- who would be fostered out -- came along, including Joseph Hendrix (b. 1949), Cathy Ira Hendrix (b. 1950) and Pamela Marguerite Hendrix (b. 1951).

In December of that same year, the couple was finally divorced and Al essentially took over raising Jimmy and Leon. While Jimmy began attending Horace Mann Elementary School (2410 E Cherry Street), Al took on multiple menial jobs including janitor, gas station attendant, and finally gardener. During those days of struggle, Jimmy and Leon were both taken in at times by relatives, friends, neighbors, and perhaps a half-dozen foster homes.

But Al eventually stabilized his situation enough that Jimmy rejoined him (at the house he'd bought back in 1950 at 2603 S Washington Street) and and Al did what he could to provide -- including bringing home an old used ukulele for his oldest son. By the mid-1950s Jimmy was enrolled at Leschi Elementary School (135 32nd Avenue) where he played on their Fighting Irish football team. Jimmy and his boyhood pals -- like most all Seattle kids -- were huge fans of the Seafair festival’s hydroplane races on nearby Lake Washington, and he also loved listening to the radio and playing Al’s small collection of jazz and blues records.

Jimmy’s Blues

With the dawn of rock ‘n’ roll as a popular form of youth-oriented music in the 1950s, Jimmy and his pals became obsessed with the new sounds. Initially the only radio stations to feature big-beat music were tiny FM operations in Bremerton and Tacoma that aired specialty shows hosted by local pioneering African American DJs like Bob Summerise (1925-2010) and Fitzgerald “Eager” Beaver (1922-1992). But by 1957 even pop/Top-40 stations had to play the early big hits by Elvis Presley -- and the subsequent legions of other Southern rockabillies and Hollywood-based wannabes that would emerge.

It was in September 1957 that Presley’s band electrified Seattle with a concert at the Sicks’ Stadium ballpark near the Hendrix’s neighborhood -- but even though various publications have reported that the then-15-year-old Jimmy attended, no proof of that assertion exists, and his family’s precarious financial state would seem to cast further doubt on it. What is certain is that a cartoon sketch of Presley and his guitar was drawn by young Jimmy, and survives in his family’s archives.

It was also in about 1957 that Al bought an old used acoustic guitar for $5 and gave it to Jimmy, who immediately began teaching himself to tune and play chords on it -- in particular, the foolproof-but-addictive three chords to the region’s signature tune, “Louie Louie.” Jimmy also began to jam to songs on the radio and to theme songs from various television shows. By 1958 Jimmy was studying at Meany Junior High School (301 21st Avenue E) and making new friends. It was probably in 1959 that Al was able to afford a cheap Supro Ozark electric guitar from the Myers Music shop (1214 1st Avenue) downtown.

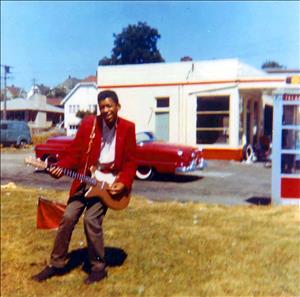

Undoubtedly grateful, Jimmy must also have been a bit frustrated that his father was never able to spare the cash to match that guitar with an amplifier. For the next years would always be reliant on sharing or borrowing the amps of his friends. And it was with such neighborhood friends as Pernell Alexander, Butch Snipes, and Luther Rabb that he began jamming after school. Alexander and Rabb were among the members of the first band that Jimmy helped form: the Velvetones. Though the band-members were far too young to play nightclubs, they honed their skills playing teen-dances in venues including recreation halls at area housing projects including Yesler Terrace in Seattle’s Central District. Before long Jimmy’s left-handed guitar playing had advanced to the degree that his peers became admirers. The Velvetones even began to include his original tune, “Jimmy’s Blues,” in their dance sets.

Time passed and Jimmy was invited to join another band -- the Rocking Teens -- who soon changed monikers to the Rocking Kings. Meanwhile, Jimmy became enthralled with the sounds being created by various top-tier local bands -- especially Seattle’s Dave Lewis Combo, the Playboys and Dynamics, and Tacoma’s Wailers -- and he undoubtedly ached to belong to a group that had the potential to break out of the small-time scene of house party, community hall, and rec center gigs his bands had been trapped in.

That opportunity arose around 1960 when he was invited to join James Thomas and His Tomcats, a new combo assembled, managed, and fronted by an older guy who had a sense for business and successfully got his band booked at good gigs such as Seafair picnics and military officers clubs ranging from the U.S. Naval facility (at Seattle's Pier 91) to Everett's Paine Field to Fort Lewis to Moses Lake's Larson Air Force Base and back. By this time Jimmy had acquired a new Danelectro guitar to replace one stolen during a gig at the Birdland nightspot (2203 E Madison).

Drivin’ South

It was while attending Garfield High School (400 23rd Avenue) that Jimmy first began to get himself in trouble. Years later he would claim that he was expelled for smart-mouthing a teacher, but school records only show that he dropped out. Although he began to work alongside his father in the yard-care business, Jimmy had a greater taste for flashy clothes than he could afford and he reportedly got involved in a few acts of burglary at retail shops. Even more seriously, in the spring of 1961 he was arrested twice in one week for the same crime of riding in a stolen car. Back in those days judges often allowed young defendants an optional out from being sentenced to jail: that of joining the military instead. By June Jimmy was sweating in basic training at Fort Ord, California, and soon after was stationed at Fort Campbell, Kentucky.

It was then that Jimmy mailed a letter to Al requesting that his Danelectro guitar be shipped down, and upon its arrival he would often practice playing it on base during his free hours. That was how he crossed paths with a bass-playing soldier named Billy Cox who heard this music from a distance and was immediately impressed by the unseen guitarist’s profound technique and musical acumen, later reminiscing that it came from a creative musical space “somewhere between Beethoven and John Lee Hooker” (Shapiro and Glebbeek, pp. 60-61). The two troopers hit it off and soon formed a combo, the King Kasuals, to play gigs around the adjacent Clarksville, Tennessee area. Long-story-short: Jimmy had difficulty managing his personal finances and was always frustrating his bandmates by pawning his guitar to raise a few bucks. Worse yet, at one point he actually sold his guitar to another soldier. Upon being discharged from the 101st Airborne Division in 1962 he begged the fellow to loan it back so he could find work.

Interestingly, years later Hendrix would claim that he’d been cut loose by the army because he’d broken his ankle during a parachute-training jump. Yet in 2005 some of his military records were released under a Freedom of Information Act request (posted at TheSmokingGun.com), which reveal that the guitarist had been a rather problematic soldier -- one who, among other infractions, was "unable to conform to military rules and regulations," and was severely distracted "while performing duties" due to excessive "thinking about his guitar" -- which led to a recommendation that he be discharged under Army Regulation #635-208, the classification for "Undesirable" status.

In addition, Charles R. Cross's 2005 biography references other army medical documents that show that Jimmy actually declared himself to have homosexual tendencies (a surefire way to get mustered out early). Though Hendrix earned a bit of a reputation as a teller of tall tales, his service did finally end -- for whatever reason, or combinations thereof -- on July 2, 1962.

Highway Chile

Upon Billy Cox’s discharge around September, he and Jimmy scrambled around putting together a new lineup of the King Kasuals and aimed their sights on the black nightclub scene in Nashville. Scoring gigs at the Del Morocco and the Jolly Roger clubs the guys figured they were making inroads into the music biz and they even reportedly hired on in support of a few soul stars including Carla Thomas, the Marvelettes, and Curtis Mayfield.

His father once recalled that at a couple points Jimmy became flush enough to afford train tickets back for visits to Seattle and it is also known that he visited his grandmother Nora in Vancouver during one Christmas season. That was where he sat in with, and briefly joined the town’s top club act, Bobby Taylor and the Vancouvers, who had an extended engagement at the Dante’s Inferno venue.

Some sources have insisted that that was where the 1950s rock ‘n’ roll icon, Little Richard, first discovered Hendrix. What is certain is that in time the promising young guitarist would ultimately join the star’s band, and tour and record (“I Don’t Know What You’ve Got But It’s Got Me”) with them. Hendrix himself would later confuse the record by making some possibly fanciful claims in media interviews regarding which other stars he played with along the way -- singers like Sam Cooke and Jackie Wilson included -- but it is a fact that after winding up in New York City in early 1964 he did join the Isley Brothers band (even touring through Seattle once with them) and record a few songs including the minor radio hit, “Testify,” which in hindsight contains a tantalizing little flash of his guitar-playing prowess.

Rejoining Little Richard, Jimmy ended up back on the West Coast and while in Los Angeles he played in a recording session for a girl singer, Rosa Lee Brooks, which produced another early disc with Hendrix’s guitar-work, “My Diary.” Then, settled back in New York City once again, Jimmy played with a few club bands including Curtis Knight and the Squires, and did recording sessions with Lonnie Youngblood -- and even one with the King Curtis Orchestra: Ray Sharpe’s “Help Me,” which was released by a major label, Atco Records.

Jimi Emerges

In late 1965, he formed Jimmy James and the Blue Flames and they played in various Greenwich Village coffee houses and nightclubs. Within months Jimmy’s reputation as a phenomenal guitarist began to get traction. In 1966 he was spotted while performing by Linda Keith -- the British model and girlfriend to the Rolling Stone’s guitarist Keith Richards.

She stepped up and invited Jimmy over to a after-gig party and discovered that the budding guitar god was actually a shy, polite, and perfectly charming young man who suffered from self-esteem issues, the lack of adequate income, and a lack of nutrition. Feeling the need to help him out, she returned to her upscale hotel room, grabbed one of Richard’s Fender Stratocaster guitars and gave it to the grateful musician. In addition, Keith did everything she could to spread the word about Jimmy amongst all the British rock stars she knew.

Chas Chandler -- bassist with the Animals -- likewise agreed that Jimmy was a full-on rock star just waiting to be nurtured, packaged, and launched. He convinced Jimmy to fly with him back to London where he would quit the Animals and manage the guitarist’s future career. Aboard that September 23rd flight Chandler informed his protégé that he was to be marketed with an intriguing new name: Jimi Hendrix.

Once in London, auditions were held and bass guitarist Noel Redding and drummer Mitch Mitchell were selected to form the Jimi Hendrix Experience, and gigs and tours commenced after minimal rehearsals. Rock ‘n’ roll was forever transformed by Hendrix’s mind-blowing psychedelic guitar pyrotechnics and beautiful song-writing. The debut single, “Hey Joe,” was an instant hit that was quickly followed by the ground-breaking masterpiece, “Purple Haze,” and the Summer of Love classic album Are You Experienced.

Initial Brit media coverage was a mixed bag: Some critics were duly agog over the band’s virtuosity, while others couldn’t get over Hendrix’s wild appearance and lobbed racial insults like “Mau Mau” towards the emerging star. As word began to leak back stateside, a few folks in Seattle began to puzzle as to whether this “Jimi” guitar hero was in fact, the town’s own Jimmy Hendrix. That mystery was deepened when Chandler -- employing every possible opportunity to hype the musician as exotic and entirely different than any other rocker in England -- really began playing up the fact that Hendrix was an American.

In June 1967 the Jimi Hendrix Experience was booked to perform at the highly publicized Monterey International Pops Festival. It was there that their music and Jimi’s stage show (famously featuring a guitar-smashing, flambe finale) catapulted them to the top of the pop charts. Within weeks the first advertisements for a Seattle concert date were published -- albeit with the majorly embarrassing typographical hometown error which announced that “Jimmy Hendricks” would soon appear at the Eagles Auditorium (7th Avenue and Union Street) along with San Francisco’s Moby Grape (Helix).

Back Home

The year 1968 saw two additional album releases by the Jimi Hendrix Experience: Axis: Bold as Love and Electric Ladyland. Both proved to be critical and commercial successes. On February 12, 1968, Hendrix performed at the Seattle Center Arena, a venue not renowned for its acoustic qualities. Tom Robbins wrote in the Seattle countercultural newspaper Helix, "Listening to rock in the Arena is like making love in a file cabinet. It's a study in frustration." The next time the band returned to town they played on September 6, 1968, at the somewhat better Seattle Center Coliseum -- a venue they returned to on May 23, 1969..

But by June, the Experience had dissolved and Jimi began playing with varying lineups of other musicians sometimes billed as the Gypsy Suns and Rainbows or as Sky Church (which included Billy Cox, Mitch Mitchell and other players), which headlined the Woodstock rock festival in 1969. Jimi then formed a new trio, the Band of Gypsys, with Cox and ace drummer Buddy Miles (formerly with Akron, Ohio’s soft soul hitmakers, Ruby and the Romantics).

Jimi also invested in his future by building a new facility, Electric Lady Studios, in New York City -- making him one of the very few young pop musicians to have his own recording studio. Then on July 26, 1970, he returned home to play one final gig here at Seattle’s outdoor baseball park, Sicks' Stadium. Although there were reports that Hendrix held mixed feelings about his hometown, he always made a point of visiting local musician pals when visiting, and he even penned lyrics to an original song titled “West Coast Seattle Boy.”

I Don’t Live Today

The brutal life as a rock star -- constant touring, endless hassles, over-indulging in food, drinks, and recreational drugs -- finally took its greatest toll on the man. On September 18, 1970, James “Jimi” Marshall Hendrix died at age 27 while asleep in London, not of an overdose as has been so often reported, but by choking on vomit while under the influence of barbiturates and red wine.

He was buried on October 1, 1970, at Greenwood Cemetery (today’s Greenwood Memorial Park, 350 Monroe Avenue NE), in Renton, Washington. A memorial service was cancelled because of lack of time and because of official concerns about problems with crowds, but Seattle’s music community came together on January 22, 1971 with with a three-day tribute jam/concert with over 30 bands -- to benefit the hastily organized and scandal-plagued Jimi Hendrix Memorial Foundation -- at the Eagles Auditorium (7th Avenue and Union Street) to honor a lost native son.

In retrospect it is clear that Hendrix’s contributions to music cannot be overstated. He was the magic missing link between existing traditional R&B forms and progressive interstellar acid rock of the Aquarian Age; the one guitarist who sent shivers of envious fear coursing through the veins of rock ’n’ roll’s leading guitar gods: Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, and Pete Townshend; an undeniable instrumental genius who harnessed feedback, fuzztone, and wah-wah sounds to positive and influential effect. He was a major force in twentieth century music.

The high level of esteem his music is still held in by generations not yet born at the time of his death can be partially gauged by the estimated value of his estate -- which was reported as $40 million to $100 million back in 1995 when Al Hendrix succeeded in a legal brawl to regain control of it from various music biz entities. Since 1970 scores of books have been written about the man, movies have been screened, countless artists have covered his songs, and in June 2000 Seattle saw the Grand Opening of a $250-million music museum, the Experience Music Project (EMP, 325 5th Avenue N), founded in honor of Jimi Hendrix.