Alki Point, today part of West Seattle, stretches into Puget Sound to form the southern boundary of Elliott Bay. It is part of a much larger area originally inhabited by the Duwamish Indians. In September 1851, members of the Denny Party, later founders of Seattle, settled the land. One of the group, Charles Terry (1829-1867), claimed it under the Donation Land Claim Act. In 1857, Terry sold it to Dr. David Maynard (1808-1873), who later sold it to the farmer Hans Martin Hanson (1821-1900). According to legend, it was Hanson who in the 1870s hung the first lantern to mark the hazardous Alki shoals and the southern entrance into Elliott Bay. In 1913, a lighthouse was constructed on Alki Point. The Alki Point Light Station, which remains essentially the same today as when it was built, is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Settlement and Resettlement

In 1857, Charles Terry, who had founded King County’s first store at the place he called New York (later renamed Alki), decided to leave Alki, move to Seattle, and start other businesses. He sold his Alki Point claim of 320 acres to Dr. David S. Maynard in exchange for Doc Maynard’s 260 acres of unplatted real estate directly south of Yesler Way. For Maynard, this represented what was probably the worst land deal in Seattle history. Seattle was prospering whereas Alki had been forgotten. Maynard apparently wanting peace, solitude, and a really nice view, intended to farm the land. This was home to the Maynard family for the next 11 years.

For Terry, the deal was a good one. Terry was such an astute businessman that within two years, he owned 40 percent of the land within the Seattle city limits, 90 percent of which was in the central business district.

In September 1868, Dr. Maynard gave up farming. He sold his 320-acre farm on Alki Point to Hans Martin Hanson and his brother-in-law, Knud Olson, for $450. Hanson and Olson were business partners and divided the property. Hanson’s portion included the wedge-shaped piece with the point.

According to legend, the point’s first light was established during the 1870s, when farmer Hanson hung a brass kerosene lantern from a post on the side of his barn. Hanson did this as a humanitarian gesture, marking the hazardous Alki Point shoals for the ever-increasing number of vessels plying the waters of Puget Sound. This extreme point of land was only a few hundred yards south of the beach where the Denny party landed in 1851.

On August 7, 1789, the federal government established the U. S. Lighthouse Service, responsible for all aids to navigation and lighthouses. In 1852, Congress created a nine-member Lighthouse Board to oversee the service’s operation, and to improve and revise the whole system. The Lighthouse Board, actively engaged in charting and marking Puget Sound, decided Alki Point was a hazard to maritime traffic and needed an official signal light. In 1887, the U.S. Lighthouse Service replaced Hanson’s lantern with a “post lantern,” used at many locations until a permanent lighthouse could be built.

Hanson Keeps the Light Burning

Post lanterns had a drum-type lens that produced a bright fixed light and were mounted on scaffolds. The wick lamp had a large tank encircling the top of the lens with enough fuel for eight days. A Lighthouse Service tender delivered kerosene or coal oil to the beach every six months.

Since it was on his property, Hans Hanson was appointed official light keeper. He was paid $15 a month to fill the fuel tank, clean the glass, trim the wicks and light and extinguish the lamp. It was a job that required Hanson’s daily attention. His son, Edmund, his six daughters, and his niece, Linda Olson assisted him in this endeavor.

When Hans Martin Hanson died on July 26, 1900, he willed his 320-acre farm to his children. Edmund inherited the wedge-shaped tip of Alki and the light keeper’s job, which still paid only a paltry $15 a month. But, with the able assistance of his cousin Linda Olson and his children, Edmund kept the lamp burning for the next 10 years.

Enter the Bureau of Lighthouses

In 1910, the newly created Bureau of Lighthouses finally received an appropriation from Congress to build the much-needed lighthouse on Alki Point. The U. S. Lighthouse Service purchased the 1.5 acre pie-shaped property at the tip of the point from Edmund Hanson for $9,999, with plans to build a manned light station, complete with a tower, a fog signal building, two houses, and miscellaneous outbuildings.

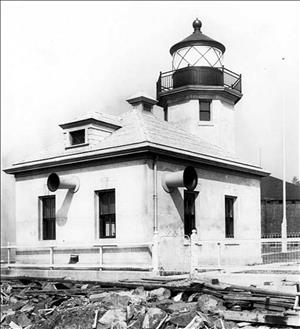

On April 1, 1913, the new Alki Point Light Station was ready for operation. The Light House Service built a 37-foot-tall octagonal concrete and masonry tower with an attached fog signal building on the most exposed part of the point. Two large houses for the lighthouse keepers and their families were built behind the lighthouse. About 7,000 yards of sand and gravel were added to the point to protect the buildings in stormy weather from heavy swells and high tides.

The two lighthouse keepers were required to keep constant vigils in alternate 12-hour shifts, seven days a week. For this, they each received a salary of $800 a year plus housing.

The Fresnel Lens

The light in the 37-foot tower at Alki Point, visible for at least 12 miles, was a fourth-order Fresnel lens, used mainly for shoals, reefs, and harbor entrance lights. Fresnel lenses capture and direct light by prismatic rings to a central bull’s-eye where it emerges as a single concentrated beam of light traveling in one direction. The lens was about two-and-a-half feet high and 20 inches in diameter, and weighed approximately 500 pounds. Each lens was made in brass-framed sections that were easy to disassemble for maintenance.

Initially, a kerosene or acetylene lamp provided illumination, but by 1918, an electric light bulb replaced the lamp. However, old lamps were always kept handy in case the electricity or light bulb failed.

The lens, resting on wheels or ball bearings, was operated by an enormous clockwork mechanism with descending weights activating the rotational movement. The turning of the lens caused the viewer of the light to see a flash, with periods of darkness. Several times a night, the keeper would have to wind the mechanism with a hand crank, raising the weights to the top of the tower, to keep the lens turning. The clockwork mechanism was replaced later with an electric motor.

The Alki Point Light Station was equipped with a Daboll three-trumpet fog signal, invented and manufactured by Celadon L. Daboll of New London, Connecticut. The signal was operated by compressed air, produced by two engines, which passed across a vibrating reed. The trumpets extended through the walls, enabling the keeper to project a distinct signal in three directions, north, south, and west.

U.S. Coast Guard

On January 15, 1915, Congress had created the U. S. Coast Guard by merging the U. S. Revenue Cutter Service and the U. S. Life Saving Service. Seattle became the headquarters for the 13th Coast Guard District. On July 7, 1939, Congress eliminated the Bureau of Lighthouses and the U. S. Lighthouse Service, transferring the responsibility for lighthouses and aids to navigation to the U. S. Coast Guard.

The civilian lighthouse keepers were allowed to remain in their jobs until retirement, and were gradually replaced with Coast Guard personnel. The last civilian lighthouse keeper at Alki Point was Albert G. Anderson, who retired in September 1970. Mr. Anderson, a lighthouse keeper since 1927, spent his last 20 years on the job at Alki. He had two Coast Guardsmen to assist him with operating and maintaining the facility.

In 1947, the original fog signal equipment was replaced with an electric single stage Worthington Air Compressor and twin Leslie-Typhon horns. Its characteristics were two blasts every 30 seconds. An auxiliary gasoline-powered Sullivan Air Compressor was installed for emergencies.

In 1962, The Alki Point Lighthouse went modern. The fourth-order Fresnel lens was replaced with an airway beacon, a rotating, reflecting light similar to those used at airports. The new beacon, which showed a flash every five seconds, was six times brighter than the Fresnel lens, 80,000 as compared to 13,000 candle power, and visible for 15 nautical miles.

On November 19, 1976, The Alki Light Station was officially designated by the Washington State Advisory Council on Historic Preservation as an historic place and listed on the Washington Heritage Register. It has also been determined that the station is eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places maintained by the National Park Service.

Automating the Beacon

Up until the 1980s, all the operations at the Alki Point Lighthouse were manual. Coast Guardsmen assigned to the station, were standing eight-hour watches, 24 hours a day, seven days a week. The airway beacon was turned on one-half hour before sunset and was turned off one-half hour after sunrise by the duty lighthouse keeper. Also, the Commander of the 13th Coast Guard District and his family lived on the light station in the Chief Lighthouse Keeper’s house.

In October 1984, the lighthouse operation was fully automated, with photoelectric cells turning the airway beacon on at night and off in the morning. Today (2003), the signal, a modern VRB-25 marine rotating beacon, operates 24 hours a day, flashing once every five seconds. Burnt out bulbs are replaced automatically and if there is a power failure, there is an emergency light located on the outside of the tower operated by 12-volt batteries. When visibility drops below three miles, photoelectric cells activate two electric FA 232 foghorns powered by a 12-volt battery system. Coast Guardsmen assigned to lighthouse duty are relegated to facility maintenance.

Although the old fog signal has been replaced by electric horns, the original fog-signal house, with its generators and compressors, is kept in pristine condition for historic purposes. The original Alki Point fourth-order Fresnel lens is on display at the Admiralty Head Lighthouse at Fort Casey on Whidby Island, but a similar lens is on display in the fog-signal house at Alki. The old post lantern placed on Alki Point in 1887 by the Lighthouse Service, can be seen at the Coast Guard Museum, Pier 36, 1519 Alaskan Way S, in Seattle.

The exterior of the lighthouse and station remains essentially the same today as when it was built in 1913. Although the lighthouse keeper’s residences are still used by Coast Guard officers, the Commander, perhaps because of the foghorn, moved his official quarters across Lake Washington, to Medina. However the foghorn was removed in August 2005, and in August 2007 the Commander will resume residence in Quarters A.

The Alki Point Lighthouse, 3201 Alki Avenue SW, is one of eight lighthouses on or near Puget Sound open to visitors.