On the afternoon of October 5, 1855, gunfire erupts between Yakama Chief Kamiakin’s 300 warriors and Major Granville O. Haller’s 84-man troop of soldiers. The two groups have been at a standoff across the ford at Toppenish Creek. Haller and his men are forced into retreat, but tensions continue to rise between Indians and settlers from Southern Oregon up to the Puget Sound region.

A Shattered Peace

Kamiakin and his people had lived in peace with the Catholic Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate who established the Saint Joseph Mission in 1852 at his invitation.

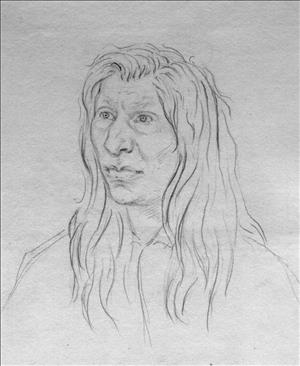

On June 9, 1855, the Yakama, Umatilla, Cayuse, and Walla Walla tribes were forced to cede in excess of six million acres to the United States government, partly as punishment for the killing by a group of young Cayuse of Methodist missionaries Marcus and Narcissa Whitman and others on November 29, 1847, an event known as the Whitman Massacre. Called the Treaty of Yakama, it was signed at Walla Walla on traditional Indian meeting grounds. The tribes were paid $200,000 over a number of years in exchange for their land. Kamiakin first refused to sign the treaty, but later did so under duress.

At the time the Treaty was signed, Washington Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens (1818-1862) assured the Native people that white miners and colonizers would not be allowed to trespass on tribal lands during the time before the treaty could be ratified by the United States Senate.

Gold strikes in the Colville area and in the Fraser River area in British Columbia, however, encouraged increasingly large groups of miners to invade tribal lands as they crossed the region en route to the gold fields. Miners were heavily laden with supplies on mules, and were sometimes known to steal horses and to greatly mistreat Indigenous women.

Some of the Yakama warriors had retaliated by killing miners in isolated incidents. In late September 1855, Andrew J. Bolon, the Indian sub-agent at The Dalles, was shot and killed while investigating these incidents. It was for this reason that Major Haller and his troops set out from The Dalles for the Yakima Valley. The fight on October 5 started the conflict that would come to be known as the Yakama (or Yakima) War.

Casualties in this first battle were low on both sides. Kamiakin had two dead, four wounded, one captured. Haller had five dead, 17 wounded. Despite the fact that reinforcements were on their way, Haller and his men were so greatly outnumbered that they slipped away under cover of night and retreated toward The Dalles. On November 9, 1855, Major Gabriel J. Rains and troops some 700-strong marched on Kamiakin and his 300 warriors on the bank of the Yakima River at Union Gap. Outnumbered more than two to one, the attack seemed to confirm the Yakama people's fear that the whites had come to exterminate them. The warriors battled as their families fled toward safety through the bitterly cold night.

In the morning the Yakama were nearly surrounded. Kamiakin ordered retreat, and the warriors’ ponies easily outdistanced the soldiers’ horses. Snow covered the ponies’ tracks. In the two days of fighting there had been only one death: a non-combatant killed by mistake by a government scout.

The soldiers vented their rage at the Saint Joseph Mission, from which the Catholic Fathers had joined the fleeing families. The soldiers found gunpowder buried in the garden and assumed that this meant the missionaries were aiding the Indians in their fight against the Army. Historians believe that actually the priests had buried the gunpowder in order to prevent Chief Kamiakin from using it to make war. The soldiers also found a letter that Kamiakin had dictated to Father Pandosy, one of the priests. The letter was addressed to the soldiers and protested the Indians' treatment. He suggested that the tribes could grant portions of their land to the whites in exchange for not being forced onto reservations.

The soldiers burned the Mission to the ground. Major Rains counted this as a form of victory.

By 1858, the Yakama had lost 90 percent of their traditional lands and were confined to a reservation. Their ability to gather their traditional foods all but destroyed, many took refuge in traditional beliefs, hoping that in time these practices would drive out the whites and restore their lands.