On Tuesday, February 13, 1979, about 7 a.m., the western half of the Hood Canal Bridge sinks during a severe storm. For several hours before the Tuesday the 13th catastrophe, a storm has battered the bridge with winds of 80 miles per hour gusting to 120 miles per hour. The bridge on State Route (SR) 104 connects the Kitsap Peninsula with the Olympic Peninsula. It is the second concrete pontoon floating bridge in Washington's highway system, and the world's first floating pontoon bridge built over salt water subject to tides.

A Floating Bridge

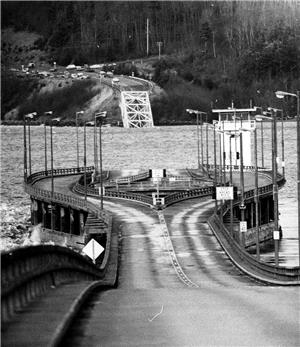

The bridge is one-and-one-fifth miles long (7,869 feet). It has approach spans and truss spans built on piers, and a center span built on 23 floating hollow concrete pontoons, each composed of 93 cells, and each weighing about 5,000 tons. These were bolted together to form two continuous rigid piers. At the center is a retractable pontoon draw span that opens to a 600-foot clearance. The floating portion was held in place by braided steel cable tied to 42 concrete-block anchors each weighing more than 500 tons.

Pontoon bridges were designed for calm lakes. Hood Canal is not a man-made canal but a fjord -- an arm of the sea -- 55 miles long and subject to heavy currents, tides, and giant waves. The water level rises and falls as much as 18 feet. Even before the bridge opened on August 12, 1961, there were engineering worries and technical problems. Storms tended to damage the bolted joints that hitched the pontoons together.

The Hood Canal Wind Tunnel

On the day of the storm, southwest winds aligned exactly with the direction of the canal, and within this huge wind tunnel the bridge was the only resisting solid object. Waves 10 to 15 feet high crashed against the bridge for hours, until finally the western floating portion sank, leaving three-quarters of a mile of open water. The last man off the bridge claimed he saw three maintenance hatches open (these provided access to the interior of the hollow concrete pontoons), and water pouring in. In the following days divers found that the storm had snapped the massive (about three feet in diameter) cables.

The bridge had always been controversial, for some peninsula people preferred a rural way of life that the bridge with its stream of traffic compromised. Some believed the bridge had been sabotaged and others believed that the Navy had cut one or more cables to let a submarine through. (The Naval Submarine Base occupies four miles of Hood Canal's eastern shore at Bangor.) However, an independent consulting firm concluded that the storm had moved three anchors tied to the first pontoon just west of the draw span and everything had gone down from there.

There was vigorous debate on what to do about the bridge. Proposed solutions ranged from ferry transportation to an underwater tunnel to a suspension bridge (very difficult to build in that extremely deep location). Ultimately, the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) decided that the most economical and efficient solution was to rebuild the western portion of the bridge.

Magnuson to the Rescue

Senator Warren Magnuson, Chair of the Senate Appropriations Committee, immediately began lobbying for federal funds. He knew how to lobby for emergency bridge funds because he had just done so on behalf of the West Seattle Bridge, which was destroyed when the freighter Chavez rammed it on June 11, 1978. The nationally notorious collapse of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge on November 7, 1940, also came to mind. The Senator sighed: "They must think we don't know how to build bridges out here at all. Every time I come around, it's for more bridge money" (Dorpat and McCoy).

Since the design of the original bridge, marine building technology had advanced considerably. In particular, much had been learned from building offshore oil-drilling platforms. The new western half of the Hood Canal Bridge was rebuilt with much heavier anchors that were pretensioned in three directions instead of in only one. The rebuilt bridge opened to traffic on October 3, 1982. As a precaution, the bridge is closed to vehicular traffic whenever winds reach 40 miles per hour and stay at that velocity for 15 minutes.

In 2003, WSDOT began the process of building a replacement for the now-older eastern portion of the bridge. Workers began building a graving dock to be used for constructing bridge components near Ediz Hook in Port Angeles. On August 16, 2003, they came across a midden -- the refuse dump of an ancient Native American village, and shortly thereafter came upon many human remains and artifacts that revealed the largely intact Klallam village of Tse-whit-zen under layers of industrial rubble and fill. Tse-whit-zen occupied the Port Angeles site for at least 2,700 years until supplanted by industrial development in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and turned out to be one of the largest and most significant archeological sites in Washington.

In response to the rediscovery of the village, WSDOT relocated its graving dock to Tacoma.