On June 20, 1917, the Spokane-based Lumber Workers Industrial Union No. 500, IWW, formally begins what will become a massive loggers' strike. The radical union calls the strike in the midst of an epidemic of small, spontaneous strikes throughout the "short-log" region (the pine log region east of the Cascades). Within two weeks logging operations within this region will cease. In another two weeks, the strike, which demands the eight-hour day and improved conditions in logging camps, will spread to Western Washington. Logging and the sawmills they supply will come to a halt. In August, in the context of World War I and the urgent need for lumber, Washington Governor Ernest Lister and the U.S. Secretary of War will persuade some logging firms to provide the eight-hour day. IWW leaders will be jailed, and by late August most loggers will return to work.

Narrow Bunks Crawling with Bedbugs

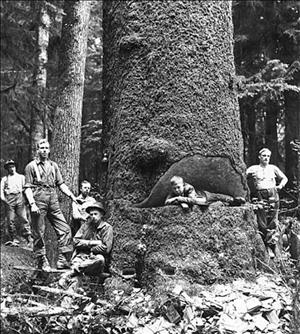

Loggers worked in the woods for an average 10-hour day and returned to a loggers' camp at night, frequently in wet and muddy clothes. In the camp there was no place to wash and no place to dry wet clothes. The food was greasy and poor.

The bunkhouse was small and unventilated to the point, in the words of one investigator, "the sweaty, steamy odors ... would asphyxiate the uninitiated" (Tyler, 90). The bedding crawled with bedbugs. One camp investigated found 80 men crowded into a crude barracks with no windows. The men pressed into tiny bunks and went to sleep "under groundhog conditions" (Tyler, 90). A study of logging camps made in the winter of 1917-1918 found that half had no bathing facilities, half had only crude wooden bunks, and half were infested with bedbugs. Employers blamed the loggers for the swarms of bedbugs and lice because loggers brought the pests in their filthy "bindles" or bedrolls.

The Strike Begins ... and Bourgeons

The Lumber Workers Industrial Union set a strike date for July 1, but loggers began walking off the job before the designated date. The union quickly re-set the date for June 20. By the end of June, logging in Eastern Washington had ceased. Pickets patrolled the camps and employers closed down the more remote camps either to avoid trouble or for lack of workers.

Strike demands varied, since the strike had actually begun as a proliferation of small, spontaneous strikes, but in general they included the eight-hour day, improved sanitary conditions in the logging camps, a payday to occur twice a month with a $60 a month minimum wage, the abolition of compulsory hospital deductions for non-existent services, and hiring through the IWW union hall instead of through employment "sharks," labor agents who provided often short-lived jobs for a price to the worker.

According to historian Robert L. Tyler, until mid-July, the IWW loggers' union had little interest in organizing loggers and sawmill workers in Western Washington. A new American Federation of Labor (AFL) union, the International Union of Timber Workers, based in Western Washington, planned to strike all the sawmills in Washington, beginning on July 16. The AFL and the IWW were rival organizations with opposing philosophies and much enmity between them. The IWW believed that the AFL planned their sawmill strike in order to lure the IWW into a support strike that would over-extend organizing capacity and weaken the organization.

However the Wobblies (the nickname for members of the IWW) soon perceived that sawmill workers in Western Washington were itching to strike. On July 14, two days before the scheduled AFL Timber Workers' strike, the IWW union called a strike for all sawmills and logging camps in Western Washington. The response, according to Tyler, was phenomenal. In the Hoquiam region alone some 3,000 loggers and mill workers answered the call. Now the two unions were allied, even if uneasily. In Grays Harbor County shipyard workers called a sympathy strike.

Employers Organize

The United States had entered World War I in April, and there was intense demand for lumber to build ships, military aircraft using Sitka spruce available only in the Pacific Northwest, and railroad freight cars. It was at this critical time that the entire lumber industry of Washington state came to a halt.

On July 9, 1917, employers established the Lumberman's Protective Association in order to maintain the 10-hour day. The industry's top leaders, including Weyerhaeuser, met in Seattle on July 17, and decided to refuse to grant an eight-hour day. The stubborn fighting spirit of the lumber firms was based on anti-union ideology rather than on self-interest: Demand was high and the firms could afford to give a little. As it was, with no lumber coming out of Washington, the U.S. War Department was forced to transfer lumber orders to rival firms in the South.

State and National Response

Governor Ernest Lister and the U.S. Secretary of War Newton D. Baker spent much of July and August attempting to end the strike. Their strategy was, firstly, to urge the firms to improve conditions and provide the eight-hour day, and secondly, to repress the IWW.

Governor Lister publicly stated his support for the eight-hour day, and announced that only 10 percent of Wobblies were "hopelessly bad men" (Tyler, 96). Since virtually all loggers in the state were at this moment Wobblies, Governor Lister's kindness toward the desperately needed work force was well considered.

On August 11, 1917, Governor Lister and the Secretary of War met with the lumber firms and lobbied them to establish an eight-hour day with time-and-one-half paid for overtime. One lumber industry journal responded by stating:

“It is really pitiable to see the government groveling in the dust and truckling to a lot of treasonable, anarchistic agitators and showing a willingness to paralyze a great industry simply to placate these agitators and doing tremendously more harm to the allied cause than the German army is doing” (Bureau of Labor).

A newly formed State Council of Defense, responsible to Governor Lister, began talks between the lumberman and the AFL Timber Workers. The firms refused to budge. Both sides considered the IWW an outlaw organization and it was not included in any talks. Indeed, key IWW leaders, considered treasonous to the war effort, were arrested and jailed.

End of the Strike

In September, the IWW, with its leaders and organizers in jail, suddenly called off the formal strike. Loggers returned to work. Some lumber companies (especially in Eastern Washington) accepted the eight-hour day and attempted to improve conditions.

But many firms started up again on the 10-hour day. IWW loggers, now back to work, continued to resist, at some camps quitting work after eight hours, at other camps working as inefficiently as possible to produce only eight hours of work in the 10 hours spent on the job.

In September the AFL Timber Workers union also ended its strike and the members returned to their work in the sawmills on the 10-hour day.