In 1852, two Californians in search of site for a lumber mill arrived at the mouth of northwest Washington’s Whatcom Creek, on the edge of the Puget Sound. The spot was close to the forests and streams they would need to supply and power their lumber business, and it had a good harbor that they could use to ship their products to market in San Francisco. The same natural bounty soon drew other newcomers. They formed four settlements: Whatcom, Sehome, Fairhaven, and Bellingham. In 1904, after a series of consolidations, the four towns became one city: Bellingham, at the time the state’s fourth-largest municipality. Yet even as the town boomed, most of its citizens -- miners, cannery workers, railroad builders, and loggers -- counted on the land and water around them for their livelihoods. At the beginning of the twenty-first century Bellingham still relies on the land to survive, but now caters to skiers, hikers, kayakers, and sightseers.

First Peoples

American Indians had lived in the Bellingham Bay area for thousands of years. The Lummi are a Coast Salish-speaking people who lived around the mouth of the Nooksack River, along the Whatcom Creek, and on the San Juan Islands. They survived by fishing, especially for salmon, and by catching shellfish. Along with the other Indian tribes of the Pacific Northwest, they developed fishing techniques that became widely used, such as the reef net, which gently guides salmon into a shallow net, and the weir, which traps salmon behind a wooden latticework fence that blocks the mouth of an estuary or stream.

In 1855, the Lummi Chief Chow’it’sut (?-1861) and other tribal leaders signed the Treaty of Point Elliott, which ceded most of the tribe’s aboriginal lands to the United States in exchange for a 15,000-acre reservation on a peninsula between Bellingham Bay and Lummi Bay. During the nineteenth century, Lummi workers from the reservation ferried goods and passengers up and down the area’s rivers and streams. They also helped white settlers build mills and houses and they worked in the logging industry.

Bellingham's Logging Industry

In December 1852, two investors from California -- Captain Henry Roeder (1824-1902), a German-born Ohioan who had earned his title as the master of a schooner on Lake Erie, and Russell V. Peabody of San Francisco -- came to Olympia, Washington, by canoe from Portland. They’d gone to Portland to start a fishing company, but when they got there they learned of a better opportunity: A fire had nearly destroyed San Francisco, and whoever managed to supply the lumber to rebuild it was going to get very, very rich. So, Roeder and Peabody headed upriver hoping to find a waterfall on which to build a water-powered sawmill.

In Olympia, they met the Lummi Chief Chow’it’sut (?-1861), who directed them to the falls at Whatcom (which meant “noisy, rumbling water”). The investors took the chief’s advice, hired a pair of Lummi guides, and kept traveling north. When they reached the falls on Bellingham Bay, they found thousands of massive Doug-fir and cedar trees along the banks of streams powerful enough to turn the mill’s heavy waterwheels. It was the perfect site. According to legend, Roeder and Peabody returned to Chow’it’sut, who gave them the falls and the timber around them. He also sent Indian workers to help build and staff the new mill.

By the time the mill was built, though, the reconstruction of San Francisco was well underway and lumber prices had fallen. Most lumber the Whatcom mill produced went north instead, where it helped to build the booming town of Victoria, British Columbia.

The Washington Colony

Fire destroyed this first Whatcom mill in 1873, and in 1881 Roeder and the Peabody heirs gave the site to a group of utopians from Kansas who promised to rebuild the mill along with a wharf, a church, a school, and 50 houses. The colonists were eventually able to do what Roeder never had -- in 1883, they delivered the area’s first large shipment of lumber to San Francisco -- but their settlement, the Washington Colony, met with little success. This is partly because it never hosted more than 25 families and partly because the Peabody heirs squabbled so much that the colonists were never free to do what they pleased on their land.

Soon the colony became paralyzed by lawsuits and mired in debt. The founders tried to solve this problem by selling stock to new investors such as J. H. Stenger, who eventually became the sole owner of the Colony Mill and other interests. In revenge, two irate colonists blew up Stenger's house with a crude bomb made out of a gunpowder cartridge and a five-gallon oil can. By 1885, the settlement was abandoned.

Advances in Logging

Lumber remained one of the leading industries in the Bellingham Bay area for nearly three-quarters of a century. By the 1880s, steam power made it possible to build mills away from streams and closer to the timber stands themselves. The enormous Bloedel-Donovan Lumber Mill processed timber right along the shores of Lake Whatcom.

Ten years later, steam-powered logging railroads made it possible to get the hugest logs from the inland mills to the Bellingham Bay for shipment. The region would have to wait for a major passenger and freight railway line, but these logging trains meant that builders all over the world could use Whatcom County lumber.

Bellingham Coal

Coal mining began in the Bellingham area in 1852, when William R. Pattle, the area’s first white settler, discovered coal on his land. The Pattle mine didn’t stay open for long and never made any money, but it inspired other would-be coal magnates to give mining a try.

Henry Roeder discovered a 17-foot-thick seam of coal on his land, mined 60 tons of it, sold it in San Francisco for $16 a ton, then sold the tract to the California-based Bellingham Bay Coal Company. That firm soon opened the Sehome mine (named after Sea-hom, a Samish leader and the father-in-law of its manager). The Sehome mine became for a time the largest employer in the Territory, and the town that grew up around it contained a company store, miners' houses, saloons, and boarding houses. Despite difficult conditions -- tunnel collapses, fires, and floods -- the Sehome mine ran for two decades. It closed in 1878, and 20 families stayed in the town of Sehome.

In 1856, the U.S. Army sent Captain George E. Pickett (1825-1875), later famous for leading the famously disastrous Confederate charge at the Battle of Gettysburg, to build a fort on the bay to protect the Sehome mine against Indian raiders from the north.

Another mine opened in 1891 at Blue Canyon on the upper end of Lake Whatcom. The Blue Canyon mine operated for 25 years until 1917. Its most important customer was the U.S. Navy, which used the coal to fuel ships in the North Pacific fleet. In 1895, the Blue Canyon mine exploded, killing 23 miners in one of the worst industrial accident in the state’s history.

The Fraser River Gold Rush

Bellinghamians also sought to get rich from other kinds of mining. In 1858, prospectors found gold on the banks of the Fraser River in British Columbia -- and Whatcom was sitting in the middle of the shortcut from the ocean to the gold. Thousands of would-be miners swarmed into the town and camped on the beach while they waited for road-builders to finish the Whatcom Trail to Canada.

Unfortunately, by the time the trail was finished, so were the Fraser River gold-fields: they had moved upriver and east to the Cariboo Basin. Besides, the Canadian government had begun to require that gold-seekers stop in Victoria to obtain supplies and permits. So, as quickly as it had arrived, the Bellingham Bay gold boom evaporated.

Hoping for a Railroad

By the 1880s, it seemed clear that, in order to really prosper, the Bellingham Bay area needed a railroad. Local boosters hoped to make one of the Bay towns the terminus of a transcontinental railway line. As early as 1854, when the U.S. Congress authorized the Corps of Topographic Engineers to survey all potential rail routes from east to west, Bellingham Bay settlers speculated that the area could win the economic and cultural investment that a transcontinental railroad would bring. But it wasn’t until 1864, when Congress chartered the Northern Pacific Railroad from Lake Superior to Puget Sound, that boosters had something real to pin their hopes on. The Northern Pacific dashed those hopes when, in 1873, it chose Tacoma to be its terminus.

Then, in the 1880s, the Bellingham Bay Improvement Company and the developer Nelson Bennett promoted real-estate speculation around the bay in anticipation of the selection of Fairhaven to be the western headquarters of the transcontinental Great Northern Railway. Developers put up buildings in downtown Fairhaven so quickly that they forgot to leave space for alleys behind them. But the railroad went to Seattle instead. In the end, it was smaller companies like the Bellingham Bay & British Columbia and the Fairhaven & Southern that connected communities on the bay to Canada, Seattle, and the logging camps and tiny towns in the hinterlands.

Two Towns, One City

By 1890, there were four towns on Bellingham Bay: Whatcom (now Bellingham’s Old Town district), Sehome (Bellingham’s downtown), Bellingham (near Boulevard Park), and Fairhaven (today’s Fairhaven neighborhood). That year, a developer from Fairhaven bought and incorporated tiny Bellingham. A year after that, Whatcom and Sehome merged to become New Whatcom, which changed its name back to Whatcom in 1901. Whatcom and Fairhaven shared a street grid and an electric streetcar system. Although some Fairhaven citizens urged restraint, fearing that the larger Whatcom would swallow their tiny town and strangle its businesses, as the towns grew it became clear to most that consolidation was the best way to ensure that they would prosper.

If there was going to be a new city, boosters decided, it needed a new name. This decision was a practical one: if Whatcom had tried to annex Fairhaven or vice versa, two-thirds of the annexed city’s voters would have to approve the merger, but if the two consolidated under a new name, only half of each town’s voters had to give their consent. Consolidation-boosters proposed the name Bellingham as a compromise (one snide newspaper editor suggested that “Whathaven” might be a better choice), and in 1903, the men of Fairhaven and Whatcom voted 2,163 to 596 to become the city of Bellingham. The new city was ready to face the twentieth century.

Salmon and the Canneries

Legend has it that farmers and gardeners could catch the Chinook salmon they used as fertilizer simply by sticking a pitchfork into a stream and flipping forkfuls of fish onto their fields. The salmon industry really began to boom around 1900, when companies figured out how to can and ship all the tons of fish they caught in their traps. Fish traps were wire nets that blocked salmon runs and forced the fish into big underwater pens. One fish trap could hold about 30 tons of fish. Workers filled boats with the trapped fish and return to the cannery, where they would clean the fish, pack it into sheet-metal cans, and prepare it for shipment.

From 1900 until about 1945, canneries such as the Pacific-American Fisheries, the Bellingham Canning Company, and the Puget Sound Canning Company were the area’s largest employers. The Pacific-American Fisheries cannery was the largest structure in Washington and the largest Pacific salmon processing-plant in the world.

Bellingham's Immigrant Workers

Many immigrants worked in these canneries (as well as for companies that served the fishing industry, such as the Pacific Sheet Metal Works and the Fairhaven Shipyard). They came from Sweden, Norway, Slovenia, and Italy to work on ships and in the canning factories.

Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino workers also worked in the canneries. They often did the dirtiest, smelliest jobs like gutting and cleaning the fish. And they weren’t welcome in Bellingham itself: They slept in a segregated bunkhouse near the cannery. The racist attitudes that Asian immigrant workers faced sometimes turned violent. During the 1880s anti-Chinese violence flared across the West and in Bellingham, in 1885, civic leaders campaigned to drive Chinese workers away from the area. When they succeeded, the towns celebrated with a torchlight parade.

In 1907, a mob of several hundred white workers went to mills and boardinghouses along the Bellingham waterfront in search of the hundred or so East Indians who worked in the lumber mills. These men were furious because they thought East Indian workers were taking their jobs away by agreeing to work longer hours for lower pay.

The white men beat all the Asians they found and ran them out of town. The next day, the remaining East Indians in the city fled. Then anonymous letters began to circulate, warning that the Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino workers who stayed in Bellingham would meet the same fate. There was never another riot in the city, but the Asian population declined anyway. Canneries began to use a mechanical fish-cleaning device that eliminated jobs that many Asian workers had held. The Asian population declined from 600 in 1900 to 240 in 1910 to 69 in 1920.

Education

Education was always an important part of the identity of the four towns that would one day make up Bellingham. In fact, the first thing the Whatcom County commissioners did at their inaugural meeting in 1854 was to levy a school tax. (The federal government required each territory it created to make provision for a public school system.) In 1890, the town of Sehome built the Northwest’s first high school. That first year, it served 33 pupils.

But the most important school in Whatcom County was the New Whatcom Normal School. In 1895, the school Location Commission chose a drained marsh on the top of Sehome Hill to build a new normal school, the state’s third. The purpose of a normal school, according to the state legislature, was “to train teachers in the art of instructing and governing in the public schools” (Gregoire). It gave young women and a few young men the training they needed to be teachers in the rural communities around the Bellingham Bay.

The New Whatcom Normal School started in a single building called Old Main that was completed in 1899. That’s where students went to class, studied, and ate their meals. They didn’t need to stay at the Normal School for long -- it took only a year to train to become an elementary school teacher. But by 1933, state law required that teachers have at least three years of college, and the Normal School’s curriculum had changed so much that the state granted it the power to award bachelor’s degrees in education.

The school became the Western Washington College of Education. After World War II, the college boomed. Soldiers who might never have considered going to college before the war could suddenly use the GI Bill to pay their tuition and living expenses while they continued their education. By 1947, students at Western Washington could get bachelor’s degrees in chemistry and English as well as in Education. The school continued to expand, and in 1961 it became Western Washington State College. It’s been Western Washington University since 1977. Today, Western Washington is a highly ranked public university with about 13,000 undergraduate students in many majors.

A Thriving Town

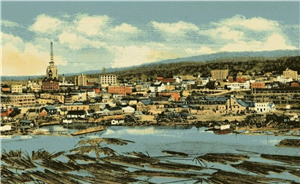

During the early part of the twentieth century, Bellingham boomed. Railroad speculators built many ornate and imposing buildings in downtown Fairhaven. Bankers and merchants built homes and office buildings in Sehome. As the canneries and lumber mills prospered, the streets of the Bellingham Bay towns came to look more and more established and respectable.

In 1891, local architect Alfred Lee (1843–1933) designed the Whatcom City Hall in the Second Empire style. It was a tall, three-dimensional building with a mansard roof and a dramatic clock tower. (The clocks themselves didn’t tell time at first. The depression of 1893 meant that there was no money to complete the interior of the building or to buy working clock parts, so the city simply fixed the clock hands at 7:00.) In 1939 Bellingham built a larger, more modern city hall on Lottie Street. Since then, the Old City Hall building has housed the Whatcom Museum of History & Art.

In 1903, Fairhaven got a grant to build the area’s first Carnegie-funded library on 12th Street. That library still stands today. In 1906, Bellingham became one of only two cities in the country to win a second Carnegie grant. The downtown-Bellingham Carnegie library opened in 1908. It sat on a high, rocky hill, and in order to get to the front door patrons had to climb 57 steep steps. Almost immediately, library boosters started looking around for a new site for the city’s central library, but they didn’t get one until 1951. Two years after that, the Carnegie building was torn down and the hill regraded.

In 1912, British architect F. Stanley Piper began work on the Bellingham National Bank, a five-story Chicago-style building that was dramatically different from the heavy-looking Victorian and Romanesque buildings railroad speculators had built. Until the Bellingham Herald finished its building in 1926, the National Bank building was the largest and most architecturally fashionable building in the city. It made clear to residents and visitors alike that Bellingham was a place to be reckoned with.

Post-Industrial Bellingham

By the mid-1950s, extractive industries like lumber, fisheries, and coal no longer formed the center of Bellingham’s economy and identity. Salmon stocks and timber supplies were depleted. The sawmills, shingle mills, and canneries had closed. The commercial fisheries on the waterfront disappeared. The downtown core, built around businesses that served mill and cannery workers and their families, declined too.

City boosters thought that they could save Bellingham by attracting a new, multi-lane highway that would run along the waterfront and make it easy for travelers, workers, and customers to visit the businesses that remained in the city. They also hoped that a modern highway would encourage new factories and other kinds of businesses to move to Bellingham.

The Idea of I-5

Bellingham boosters had always known that transportation networks were essential to their town’s survival, and in the 1950s they lobbied for their preferred route for the new highway, Interstate 5, with the same intensity that their predecessors had lobbied for railroads and interurban electric rail lines. They wanted to be sure that all traffic between Seattle and Vancouver had to drive right through the center of their city, not around it.

The old highway, the cramped and crowded Route 99, had made it easy to get to the town’s Central Business District and industrial outskirts. But as the city’s local industries declined in the 1940s and 1950s, it lost its clout in highway-building negotiations. State road planners saw that a good deal of industrial and residential development was happening outside city limits (and outside Bellingham’s tax base).

They planned a highway whose interchanges served such suburban enterprises as the Bellingham Mall (1960s) instead of firms on the Bellingham waterfront such as Pacific American Fisheries, the Puget Sound Pulp and Timber Company Mill, the Squalicum Creek industrial area, and Bellingham Coal Mine. The route's placement and interchanges then encouraged the development of suburban places at the expense of the city they’d once relied on. But this didn't prevent people in Bellingham from losing homes and businesses to the road, as it carved apart neighborhoods that people had lived in for decades.

Still, the final route spared the neighborhood that had once been downtown Fairhaven. (The route the Bellingham boosters proposed would have required the roadbuilders to bulldoze the whole place.) Even so, by the early 1970s that neighborhood, like so many others across the country, was crumbling. Abandoned buildings and vacant lots lined its streets. People didn’t feel safe there, so they stayed away.

The New Bellingham

Neighborhood and community groups decided to try to save the city they loved. Because Fairhaven had been the site of a speculative frenzy in the 1890s, when people thought it would become the terminus of a transcontinental railroad, it had many beautiful old buildings. And ever since the imposing Fairhaven Hotel had been torn down and replaced by a filling station in 1953, the people of the neighborhood had been wary of “improvements” that required them to destroy what made the place unique.

By the 1970s, the rest of the country had begun to come around to this way of thinking. Even developers were beginning to see how important it was to rescue and reuse old buildings. In Fairhaven, they built tourist-oriented shops and restaurants in some of the most distinctive old buildings, like the huge Mason Block. Preservationists worked to save others, such as the Carnegie Library and the Kulshan Club, once Fairhaven’s leading men’s club. Finally, the federal government added slightly more than three blocks of downtown Fairhaven to the National Register of Historic Places. Today, Fairhaven is packed with shops and restaurants, and concerts and movie-screenings on its refurbished Village Green attract people from all over the region.