On February 5, 1951, a lawsuit brought by members of the Albert Bishop family against Vashon Island resident Betty MacDonald (1907-1958), author of the bestselling book The Egg and I, begins in King County Superior Court in Seattle. MacDonald's husband, Donald C. MacDonald (1910-1975), the book's publisher J. B. Lippincott, Pocket Books (which issued a 25-cent paperback edition), and The Bon Marché department store are named as co-defendants in the suit.

Good-Natured But Slatternly?

The plaintiffs were Albert Bishop and his six sons, two daughters, and one daughter-in-law, all former or current residents of Jefferson County, and Raymond H. Johnson, then living in Seattle. The Bishop children were brothers Herbert, Wilbur, Eugene, Arthur, Charles, and Walter Bishop, sisters Edith Bishop Stark and Madeline Bishop Holmes, and Herbert Bishop's wife, Janet Bishop. The Bishop family alleged that they had been depicted by MacDonald as the good natured but slatternly Kettle family in The Egg and I. Johnson alleged that he was depicted as Crowbar, an Indian. All claimed to have been subjected to shame and humiliation because they had been identified with the characters in the book, which topped national non-fiction best seller lists well into its second year in print.

Albert Bishop, age 87, who alleged he was depicted as Pa (also spelled Paw) Kettle, was too ill to appear in court and his wife Suzanne Bishop, whom the family identified as the inspiration for Ma/Maw Kettle, was deceased, but the rest of the family was present in court each day of the trial. George H. Crandell and Frank C. Trunk represented the plaintiffs.

The 11 complaints were consolidated and heard at a single trial. Each Bishop asked for damages of $100,000 and Johnson sought $75,000. (Husband and wife Herbert and Janet Bishop asked for $100,000 jointly.) The case was tried in front of a civil jury in King County Superior Court. Judge William Wilkins (1897-1995) presided. Judge Wilkins had served as a member of the United States Military Tribunal in Nuremberg, Germany in the trial of the Krupp Munitions case in the wake of World War II.

George Guttormsen, Jack P. Scholfield, DeWitt Williams, Benjamin O. Frick, and J. Paul Coie comprised the defense counsel. The jury was made up of three women and nine men.

Newspaper accounts of the two-week trial mention that Judge Wilkins had a copy of The Egg and I in court and followed passages as they were read aloud during questioning, and that many spectators also brought copies of Egg into the courtroom.

The Bon Marché, Inc., named in the suit because Seattle's Bon Marché Department Store had been a major distributor of the book, was later dismissed as a defendant on the grounds that it did not operate the store. Allied Stores, Inc., operated the Bon Marché at the time. Pocket Books apparently was never served with legal papers and was not represented in court.

Fine Kettles Of Cash

MacDonald's financial success was much trumpeted by local newspapers. The book had topped the million-copy sales mark in less than a year, and sales continued to climb.

Egg had been released by Universal Pictures in 1947 in film form starring Claudette Colbert (1903-1996) and Fred MacMurray (1908-1981) in the roles of Betty and her first husband, Bob. Marjorie Main (1890-1975) and Percy Kilbride (1888-1964) played Ma and Pa Kettle, and Main was nominated for an Academy Award as Best Supporting Actress for her performance.

MacDonald was widely reported to have been paid $100,000 for the screen rights alone. The New York Times, calling the book "Betty MacDonald's non-fiction best-seller" reported, "The deal provides a $100,000 down payment and a percentage arrangement based on profits which may bring the author's total share to $250,000" (April 19, 1946, p. 26). The film was not set in Washington, but rather in some unnamed East Coast/Appalachian amalgam, and the Kettles were portrayed as broadly stereotypical hillbillies. Main and Kilbride had reprised their roles in Ma and Pa Kettle (1949) and Ma and Pa Kettle Go To Town (1950), both popular with movie goers, and the film series seemed destined to continue.

On October 15, 1949, The Seattle Times reported, "Here is how Betty collects without scratching a pen to paper: Every time (Universal) puts Marjorie Main and Percy Kilbride into another rollicking 'Ma and Pa Kettle' venture, a check wings its way to the writer. That's because she originated that fabulous couple with the 18 children. Two sequels to the original 'The Egg and I' have been made and with exhibitors reporting that they're one of the hottest bets at the box office today, it would appear Miss MacDonald is going to collect for a long time" ("Betty MacDonald Gets Movie Pay ..."). Betty's Kettle family had been depicted as having 15 children, not 18. Albert and Suzanne Bishop had 13 children. For anyone who felt they had been libeled by the book, MacDonald's obvious success must have rankled.

The Predecessor Lawsuit

Ironically, a January 19, 1947, article in The Sunday Oregonian about Egg's transformation into a motion picture stated, "After the contract for 'The Egg' was signed publishers sent out attorneys with fine-toothed combs and noses for libel suits. It was decided to eliminate a juicy chapter on the mountain moonshiner and no suits have resulted from Mrs. Hick's liver or the Kettle's immodestly located outhouse" ("Oh, M'Donald Had A Hen...").

Lippincott's attorneys evidently didn't sniff hard enough. Perhaps goaded into action by The Sunday Oregonian article, on March 25, 1947, Edward A. Bishop and Ilah M. Bishop, a married couple farming in Center, filed suit against MacDonald and her husband Donald, asking $100,000 in damages. They alleged that they were MacDonald's models for Egg's Mr. and Mrs. Hicks characters, that the book was libelous and an invasion of their right to privacy, and that they had been exposed to ridicule, hatred, and contempt because of their alleged portrayal. In the book the characters are introduced as follows: "Mr. Hicks, a large ruddy dullard, walked gingerly through life, being careful not to get dirt on anything or in any way to irritate Mrs. Hicks, whom he regarded as a cross between Mary Magdalene and the County Agent" (p. 125). In the book the Hicks and the Kettles are Betty and Bob's nearest neighbors.

After two years of legal maneuvering the case was moving toward a jury trial when the two sets of attorneys (the firms of Emery Rowe, Davis, and Riese for the plaintiffs and Laugh, Laughlin and Guttormsen for the defendants) jointly filed a stipulation for dismissal on May 4, 1949. On May 28, 1949, this case was dismissed. Neither plaintiff was called to testify at the 1951 trial.

Fiction, or Nonfiction?

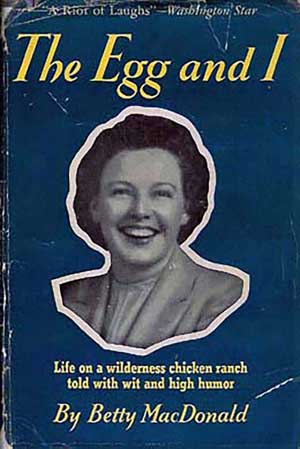

The Egg and I topped nonfiction best seller lists for more than two years. Betty MacDonald's cheerfully smiling face was used on the book's cover, and the book was clearly marketed as depicting actual events in Betty's life. Although she obscured place names (substituting Town for Port Townsend, Crossroads for Chimacum, and Docktown for Port Hadlock, for example) and frankly fictionalized the book's conclusion in which the Betty and Bob characters apparently start over on a new chicken ranch in or near Seattle, general consensus up until the time of the trial seems to have been that Betty's book was indeed nonfiction.

The outcome of the trial hinged largely on the question of whether or not Betty MacDonald invented the colorful fictional Kettles, or whether she invaded the privacy of her former Center neighbors, exaggerating their foibles. The two-week trial generated front page coverage in both the Seattle Post-Intelligencer and The Seattle Times, pitted Betty and the Bishops against one another on the witness stand, and ultimately, exonerated the enormously popular author.