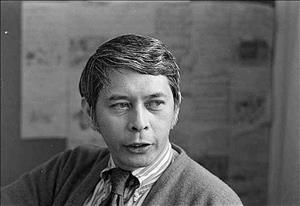

Bob Santos, born and raised in Seattle's Chinatown-International District, spent most of his life as an activist in his old neighborhood -- saving it, nurturing it, defending it against outside threats, whether environmental, cultural, or political. Dubbed unofficial mayor of the ID and Uncle Bob, was arrested six times fighting for civil rights, and he served as the Pacific Northwest's Housing and Urban Development director during the Clinton administration. "Santos gained prominence ... as an activist who could walk that thin line between being a provocateur and a peacemaker. With a famously salty tongue tempered by a gentleman's graciousness, he helped secure affordable housing, child-care services and social outlets for the elderly in the neighborhood" (Beason). Santos is also honored for what he helped keep out -- a garbage incinerator, a prison or work-release facility, a transportation hub, and a McDonald's.

International Beginnings

Robert "Bob" Nicholas Santos was born on February 25, 1934, in Seattle to Marcario "Sammy" Santos and Virginia Nicol Santos. His older brother, Sammy Jr., was born in 1932. Marcario, born in 1902, came from San Mateo, Rizal, part of metropolitan Manila in the Philippines. Opportunities for young Filipino men were limited, so Marcario joined the U.S. Navy, which still was a major presence in the Philippines at the time. (After the Spanish-American War of 1898, the United States annexed the Philippines, one of the prizes of its late-nineteenth-century imperialistic excursions. Guerrilla warfare continued until 1913 and independence finally was granted in 1946.)

While in the navy, Marcario got into a fight with an officer in about 1919, and he jumped ship in California, going absent without leave. He turned to boxing to support himself, changing his name to Sammy to avoid the military police, but he was caught and did some brig time. He fought around the country as a lightweight, "Sockin' Sammy" Santos, and settled in Seattle, a good fight town. He was a local sports hero.

In 1931, Sammy married Virginia Nicol, a beautiful Filipina who worked as a waitress at Sammy's hangout, the Rizal Cafe, while attending the University of Washington. Virginia's father, Cornelias Nicol, had immigrated to Canada from the Philippines in 1905 and found work in a British Columbia sawmill. He married Adaline Gilbert, a Native Canadian-French Canadian whose family was from Fox Island, which was Tlingit country, and from Quebec. Cornelias and Adaline had three children -- Lawrence, Antonia (Toni), and Virginia. Adaline died when the children were young, and Cornelias alighted in Seattle, where the children attended Broadway High School.

In the Filipino community, children with indigenous and Filipino heritage are called Indipino. Under the antimiscegenation laws in 16 states -- not repealed nationally until 1967 -- Asian men (or blacks) could not legally marry Caucasian women, and many found companions in the Native American population. Indipino children were not always accepted by full-blooded Filipinos and Caucasians, and many "gravitated to the Native American side of the family," Bob Santos said. "I didn't notice it then" (Chesley interview).

Taking Root in the ID

Bob's mother, Virginia, was stricken with tuberculosis and died in 1935, at age 23. Sammy Jr., Bob's brother, was sent to live with their great-grandmother, Caroline Gilbert, in Tacoma. Bob lived with his aunt and uncle, Toni and Joe Adriatico, in Seattle's Central Area.

But the boys spent weekends with their dad, who had a room in the International District's Northern Pacific Hotel. "We had a hot plate and all our worldly possessions were in one closet" (Watson). In 1945, after an unsuccessful operation, Sammy Sr. went blind and Bob would take him for walks to his old hangouts. Sockin' Sammy was a neighborhood hero and introduced Bob and his brother to his haunts -- the restaurants, pool halls, and gambling dens. Seattle's International District "was the only location in the United States where various Asian immigrants settled together" (Chesley interview).

Bob's other life, with Aunt Toni and Uncle Joe, was more conventional. He attended Maryknoll School for kindergarten and first grade, but its student body was overwhelmingly Japanese, and when Japanese Americans were interned in February 1942 the school was closed. It was Bob's first recognized exposure to racism. "We wore badges, 'I am Filipino,' 'I am Chinese,'" he said, to avoid being beaten up by white bullies (Chesley interview). He transferred to Immaculate Conception School and then attended O'Dea High School.

Racism was a fact of American life in the 1940s and 1950s, and O'Dea was no exception. "Filipino kids weren't popular unless they were athletes," Santos said. "Three friends of mine, the Laigo boys, had jobs downtown after school as busboys or waiters. There were no lockers, so they came to school dressed up. I overheard a couple of faculty refer to them as 'jitterbug hotshots.' It was wrong, branding the kids, but I didn't say anything" (Chesley interview).

Aunt Toni "was somewhat of a saint" who did chore services for the ailing, was active in Catholic charities, and took in foster children (Santos, 25). Uncle Joe, a foe of Manuel Quezon (1878-1944), the Philippines' first president, had fled the islands and shipped out, not as a steward as most Filipinos did, but on deck, as an able-bodied seaman. "We'd sit around the dinner table and he'd talk about some of the revolutionary leaders -- [Augusto] Sandino [1895-1934] in Nicaragua, [Mahatma] Gandhi [1869-1948] in India, the martyr [Jose] Rizal [1861-1896] in the Philippines. He [Uncle Joe] was a very strong union man" (Chesley interview). "It was he, more than anyone else, who first shaped my political awareness" (Santos, 25). Toni and Joe died in the 1980s.

"Pretty Straight Arrow"

Santos hung out with members of all races, doing "teen stuff." He was a "pretty straight arrow," participated in sports, and held a range of teen jobs -- delivering newspapers, waiting tables at the Pier 91 Navy Officers Club, washing dishes at G. O. Guy Drugs and Ivar's Acres of Clams on the waterfront.

He also spent two summers working at an Alaska fish cannery, a much-sought-after job for young Filipinos that could net $2,500 a season or more -- a princely sum at the time. Santos saw more racism at the cannery -- better food and quarters for white crew members than for Filipinos -- and saw the power of the Cannery Workers Union Local 7 (later Local 37), which controlled not only job allotments but also gambling in the canneries.

Santos's grades, however, "were terrible," he said. "I couldn't concentrate on my studies" (Chesley interview). He graduated from O'Dea in 1952 and joined the Marines because he wanted to fight in the Korean War. But by the time he shipped out to Korea, the armistice had been signed. Still wanting to fight, he joined the boxing team and "enjoyed the privileges of being an athlete in the service," which meant no kitchen or guard duty (Santos, 40). He fought as a lightweight and won a few bouts -- including the Fifth Air Force championship in 1954 -- but not enough to consider boxing as a career.

While he was in the service, his father remarried a woman with three children and they had three more. That union lasted 10 years, during which Santos and his father drifted apart, but they became closer after the separation. Sammy Sr. died in 1971.

Santos was discharged from the Marines in 1955 and found a job in Boeing's Renton plant, rose through the ranks, and had to battle yet more racism. He also met Anita Agbalog, who worked for Boeing as a graphics illustrator. They married in 1956, started a family, moved to a house in the Mount Baker neighborhood, and set about "pursuing the American dream" (Santos, 44).

They had six children -- Danny, Simone, Robin, Tom, John, and Nancy -- and the house "was a drop-in center for neighborhood kids" (Chesley interview). All the Santos children graduated from Franklin High School and all played sports.

An Activist Is Born

Santos left Boeing and opened a barbecue restaurant with two old buddies, Eddie and Ben Laigo, during the 1962 World's Fair, and the venture didn't fare badly. They then mounted a jazz concert at the Green Lake Aqua Theatre, featuring the Dave Brubeck Quartet and the local Joni Metcalf Trio, but an audience failed to materialize and they went bankrupt. Bob next sold insurance for the Knights of Columbus, the Catholic men's service club.

This was the early 1960s, when the various civil-rights struggles -- for African American, Asian American, Native American, Hispanic American, and women's rights -- were coalescing into marches, sit-ins, and demonstrations, from the Deep South to Seattle. A controversial war in Vietnam was rapidly unfolding and the country was entering a period of revolutionary ferment.

Santos's community involvement started innocently enough -- volunteering to coach a Knights of Columbus fitness program for neighborhood kids. He then joined the Catholic Interracial Council and the civil-rights battles -- for open housing, for equal job opportunities, for better educational opportunities. He marched to ban the Class H liquor license for private clubs that excluded nonwhites -- the Elks, Moose, and the Rainier Club. He joined United Farm Workers grape and lettuce boycott picket lines at Safeway stores and became a regular at sit-ins and other demonstrations. The demonstrations were all nonviolent, but he had a boxer's pugnacity and was arrested six times.

Through the Catholic connection, Bob met black activist Walter Hubbard Jr. (1924-2007), a United Garment Workers Union official and president of the local Catholic Interracial Council. Hubbard, who became Santos's mentor, invited him to join a march supporting open housing, a major issue for Seattle minorities -- especially blacks -- since the 1940s. Restrictive covenants in white Seattle neighborhoods prevented minorities from owning property, forcing them into virtual ghettoes -- the Central Area for blacks, the International District for Asians. Santos remembered the day as cold and stormy, and "a rite of passage" (Santos, 46).

Seattle's first sit-in for open housing took place on July 1, 1963, when members of the Central District Youth Club took over the office of Seattle mayor Gordon Clinton (b. 1920). The city council created a human rights commission, but in 1964 Seattle voters rejected an open-housing ordinance.

When Walt Hubbard became executive director of the Community Action Remedial, Instruction, Tutoring Assistance and Service (CARITAS), Santos succeeded him as chairman of the Catholic Interracial Council. When Hubbard was named to head the new King County Office for Civil Rights, Santos then took over CARITAS. In Santos's first step toward establishment recognition, Mayor Floyd Miller (1902-1985) invited him to serve on the new Seattle Human Rights Commission.

The Gang of Four

The Hubbard-Catholic connection eventually led Santos to head the Saint Peter Claver Center -- affiliated with the old Maryknoll Church and school that Santos had attended as a child, still owned by the Catholic Archdiocese. Ironically perhaps, Santos's connection with Hubbard and the Claver Center did not reinforce his own faith. "I was a practicing Catholic up until the civil rights movement, but I got into the religion of the street. So many members of the Knights of Columbus couldn't keep up with equality. They were sort of ... Republican" (Chesley interview).

Reverend Harvey McIntyre, the overextended pastor of Immaculate Conception Church, had been managing the Claver Center and asked Santos to take over. The center had become a regular meeting place for organizations ranging from the Black Panthers to the Marion Club, a group of older Catholic women. Through the center, Santos fell in with some of the region's more militant -- and successful -- civil-rights activists. They included:

- Tyree Scott (1940-2003), a black electrician and labor leader who founded the Central Contractors Association to press for more minority participation in the building trades;

- Bernie Whitebear (1937-2000), an Indipino Native American activist who created the United Indians of All Tribes Foundation;

- Larry Gossett (b. 1945), a young but seasoned radical who in 1993 would be elected a King County councilman; and

- Roberto Maestas (b. 1939), who in 1972 led the occupation of the old Beacon Hill Elementary School and transformed it into El Centro de la Raza (Center for the People) to serve the Latino community.

Gossett, Santos, Whitebear, and Maestas formed Making Our Votes Count (MOVE), concluding that change would have to come through the ballot box. They became known as the Gang of Four, occasionally the Four Amigos, and if MOVE didn't last long, they did. "We were close politically, but also socially. We liked each other," said Santos (Chesley interview).

Much later, in March 1992, the foursome would be invited oversees to smooth U.S.-Japanese relations. At the time, Japan bashing was popular, and groups on both sides of the Pacific were trying to mollify the situation with cultural exchanges. The Gang of Four was invited to Japan "to give presentations of our roles in grassroots organizing, how we interfaced with the other major minority community groups, and how we formed the Minority Executive Directors Coalition. Japan was hiring more foreign workers and wanted to figure out how best to work with these immigrants" (Chesley interview).

Getting Organized

By 1965, the International District was severely distressed. In the early 1950s, the political establishment -- including Governor Albert Rosellini (1910-2011) and Seattle's Mayor Clinton -- had bulldozed Interstate 5 through the heart of the city. The neighborhoods in its path, including the International District, objected strongly to being split, but to no avail. The freeway wiped out homes, churches, and businesses. By 1965, many of the International District hotels were closed or abandoned. More Asian Americans were joining whites in the flight to the suburbs. Housing was substandard, crime was rampant, and there was little or no social infrastructure.

Shortly after Lyndon B. Johnson (1908-1973) was re-elected president in a landslide in 1964, he pushed several elements of his Great Society program through Congress: Medicare, Medicaid, voting rights, and a War on Poverty package that included Model Cities funds for distressed areas. This would end up helping the International District.

In 1968, some activists and business owners, some of them former members of the Jackson Street Community Council (JSCC), formed the multiethnic International District Improvement Association (Inter*Im) to revitalize the area. The JSCC, formed back in 1946, "became a model for inter-ethnic cooperation" (Santos, 74). Funding from the Model Cities program helped jump-start Inter*Im, and by 1971 it was fully funded by the federal program. Santos, already on the board of directors of Inter*Im, was named executive director, and his reputation began to spread. In 1972, Governor Dan Evans (1925-2024) created the Washington State Asian American Advisory Council (later the Commission on Asian American Affairs), and Santos was one of the original commissioners.

By the mid-1970s, the Gang of Four morphed into the Minority Executive Directors Coalition (MEDC) of King County, an umbrella group representing ethnic-minority communities. By the end of 2000, there were some 120 community-based organizations in MEDC.

Kingdome Showdown

In 1968, King County voters approved a $40 million multipurpose stadium -- what would become the Kingdome -- as part of an $815.2 million Forward Thrust bond package. When the stadium was finally sited in 1971 at King Street, on the International District's fringe, the decision triggered an immediate backlash from neighborhood groups that feared a loss of low-income housing, more crime and traffic problems, more noise and light pollution -- and fast-food restaurants. (When McDonald's wanted to open a restaurant at 5th Avenue S and S Jackson Street, around 1996, Santos and his cohorts forced it to back off.)

While Inter*Im was working behind the scenes with other citizen groups to mitigate the stadium's impact, some young Asian student activists disrupted groundbreaking ceremonies on November 2, 1972, throwing snowball-sized mud balls at King County Executive John Spellman (1926-2018) and other dignitaries, and chanting "Stop the Stadium!"

The opposition to the Kingdom coalesced into the Committee for Corrective Action in the International District, which presented Spellman with six demands: a percentage of stadium profits for neighborhood social and health services; a voice in hiring a stadium manager; an Asian American on the stadium administrative staff; neighborhood preference in stadium hiring; a percentage of stadium jobs for Asian Americans; and free admission to all stadium events for elderly International District residents. "Spellman gave us a verbal commitment that all six demands would be met. We should have known better" (Santos, 87). Some of the demands were met, however.

Spellman appointed Santos to the Kingdome manager selection committee, and Santos was instrumental in hiring Ted Bowsfield, onetime major-league pitcher, as the stadium's first manager. With the help of the city's Kingdome-International District liaison officer, Diana Bower, a neighborhood health clinic was built with city, county, and state support. A legal clinic and community culture center were opened, as was a food bank, nutrition programs, and a food buying club. Neighborhood produce gardens would later be carved out of blackberry-infested vacant lots with help from volunteers.

Focus on Housing

Meanwhile, realizing that the Kingdome was a reality, Santos and others turned their attention to lobbying for more elderly low-income housing in the International District. After a march to the Seattle offices of the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) on November 14, 1972, activists demanded rehabilitation of several dilapidated International District hotels. (Some signs carried by demonstrators sported the phrase "Hum Bows, Not Hot Dogs." Hum bows are Chinese barbecued pork buns, and the message became the title of Santos's memoir.) After 1973, when HUD released funds for low-income elderly housing, Inter*Im worked with several property owners to rehabilitate or build housing projects in the neighborhood.

In 1974, Inter*Im's focus on housing increased with the creation of the International District Preservation and Development Authority to build low-income housing directly. With other community groups, such as the Chinatown Chamber of Commerce, Inter*Im drafted a charter for the organization. But trouble arose when King County Councilwoman Ruby Chow (1920-2008) and other members of the Chong Wa Benevolent Association submitted an identically worded draft, but for a "Chinatown Preservation and Development Authority." Chow, a Chinese restaurateur and civic activist, had spent much of her public career insisting on "Chinatown" as the district's identity. "Ruby ... never worked well with our diverse group of Asian American activists" (Santos, 111). "She had ideas of her own on what should happen in the community and they didn't coincide with ours. She was very ethnocentric" (Chesley interview).

In an effort at compromise, Mayor Wes Uhlman (b. 1935) in 1975 merged the charters and groups into the Seattle Chinatown-International District Preservation and Development Authority (PDA). But political infighting hampered progress until members of the Chong Wa faction left the organization, Santos said (Chesley interview).

In 1978, HUD designated the International District as a Neighborhood Strategy Area and provided assistance for private investment in elderly low-income housing programs. Tapping into that program, the Chinatown-International District PDA was able convert the New Central Hotel and Jackson Apartments into 45 low-income apartments for the elderly.

Also in 1978, the neighborhood PDA bought the old Bush Hotel, a rundown railroad hostelry built in 1916. The group used a federal urban development grant as seed money, engineered through the office of Senator Warren G. Magnuson (1905-1989). The Bush-Asia Center opened in 1981 with 200 low-income residences, a cultural center, and offices of several social service agencies. The Bush-Asia Annex was added and became home to the Wing Luke Museum, named for the Seattle city councilman who became the first Chinese American to hold such an office in a large mainland city. Later, the Annex became home to the Northwest Asian American Theatre, one of the first such Asian American theatrical groups in the country. Santos and the Gang of Four had no trouble occasionally singing, dancing, and hamming it up for theater audiences.

Funding the Struggle

The struggles for the International District involved a constant search for funds -- begging; browbeating and cajoling governments, foundations, and businesses; and staying alive by wit and wile. Inter*Im lost its Model Cities funding in 1974 and the staff of three, including Santos, temporarily collected unemployment while keeping the office open. Luckily, they shared space with the Asian Counseling and Referral Service (ACRS), which took care of the rent. Funding finally came through the federal Community Services Administration.

A parking lot became a source of income for Inter*Im -- if a sometimes troublesome one -- in 1972. The group negotiated with the state Department of Transportation (DOT) to lease space under Interstate 5, on Jackson Street between 8th and 9th streets S, for a parking lot to serve the International District. But it was too far away from the district's core and attracted little traffic until Santos convinced Mayor Uhlman to extend the city's new "Magic Carpet Zone" free bus service to the lot. The parking lot brought in about $50,000 a year for Inter*Im, and when the DOT tried to terminate the lease in 1990 the group was able to thwart the attempt.

Party Politics

Santos had been pondering political possibilities since 1970, and in 1972 he told the Democratic establishment he was interested in running for the 37th District U.S. congressional seat held by John O'Brien (1912-2007), believing that the conservative legislator "was out of touch with the minority communities" (Santos, 132). But O'Brien had been in office since 1939, was Speaker of the House pro tempore, and was one of the most powerful politicians in the state.

In 1973, when an aide to Governor Evans and other Republicans suggested that Santos run in a special election for the 35th District state Senate seat formerly held by Bob Ridder, Santos readily agreed, despite the scorn of many friends. The state Republican Party, Santos reasoned, was in the hands of moderates such as Evans, who had, among many other liberal initiatives, created advisory councils for Asian Americans and other ethnic-minority groups.

The state Republican Central Committee assigned a press coordinator -- a "glib, well-dressed, polite young man with a lot of political savvy" (Santos, 134). He was Ted Bundy (1946-1989). Bundy would be executed in Florida on January 24, 1989, linked to the murders of at least 22 young women.

Despite doorbelling help from local party stalwarts, Santos narrowly lost to Ruthe Ridder. The Watergate scandal, which would lead to the resignation of President Richard Nixon (1913-1994), was unfolding and it was not the best time to run as a Republican. Santos challenged Ruthe Ridder again the following year, as a Democrat this time, but lost again.

In 1977, the Gang of Four took a major step into establishment politics by backing Charles Royer (b. 1939) in his race against Paul Schell (1937-2014) for Seattle's mayorship. Royer won handily and one of the gang, Larry Gossett, went to work for him.

It's Criminal

In 1979 another threat to the International District appeared when various governmental agencies began laying claim to the old Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) building on Airport Way, just south of the neighborhood. King County Executive Spellman wanted a county work-release center with up to 300 beds, which outraged all segments of the Asian community, as did a 1980 U.S. Justice Department plan to house minimum-security prisoners. A 1993 U.S. Department of Corrections plan to build a 500-bed prison on city property just south of the neighborhood met similar opposition.

In 2002, the INS was absorbed into the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, and in 2004 a new immigration and detention center opened in Tacoma. The old INS Building has been vacant ever since. The building -- which is on the National Register of Historic Places -- finally was auctioned online in 2008 for $4.4 million. A group of local investors bought it, planning to turn the crumbling structure into office space with links to its historic roots as the Ellis Island of the Northwest.

Yet another potential threat to the community had arisen in 1978, when the Port of Seattle proposed a transportation hub at Union Station, on the neighborhood's western fringe. Santos and Inter*Im battled the port and the city, and a smaller version eventually was built underground at the adjacent King Street Station. Still later, in 1987, when Mayor Royer proposed a garbage-burning plant just south of the International District, Santos joined the chorus against it.

Santos also became involved in efforts to improve conditions for Filipinos working in the Alaska seafood industry and in the movement battling the corrupt Philippine dictator Ferdinand Marcos (1917-1989). But Santos was aware of the dangers of challenging the leadership of Alaska Cannery Workers Union Local 37 of the International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union, which also was corrupt. In 1991, union president and Filipino community power broker Constantine "Tony" Baruso (1928-2008) was convicted in the murder of a reformist union official, Gene Viernes. Baruso died in prison at age 80.

Challenging Chow, Representing Lowry

In 1984, Santos wanted to challenge Ruby Chow for her seat on the King County Council, but Chow decided to step down and Santos had to run against a field that included the eventual winner, Ron Sims (b. 1948). Sims would go on to become King County executive and, in 2009, Deputy Secretary of the Department of Housing and Urban Development in the Obama administration.

After his failed campaign, Santos joined the Seattle staff of U.S. Congressman Mike Lowry (1939-2017), who was involved in minority affairs. On one assignment -- El Salvador -- Santos found himself in deeper than he wanted. Lowry, an ardent foe of the United States presence in El Salvador, was asked to join a delegation seeking the release of eight Salvadoran human-rights officials arrested by the right-wing government. He sent Santos instead to join University of Washington anthropology professor Kay Hubbard and attorney Karen Parker, representing the United Nations, to negotiate the group's release. After a harrowing week, during which the trio feared for their lives, the officials were released, but to uncertain fates.

The job with Lowry disappeared in 1988 when the congressman lost his bid for the U.S. Senate to Slade Gorton (b. 1928). Santos worked briefly for Seattle's Department of Neighborhoods and in 1989 took on the executive directorship of the Chinatown-International District PDA. He was back in the housing business.

The Village Square

Santos had been harboring a dream -- an International District Village Square on a 1.66-acre property at 8th Avenue S and S Dearborn Street, used by Metro for maintenance and parking. His ambitious vision saw housing for the low-income elderly, a commercial kitchen and dining area for the elderly, office space for social service agencies, and a community center and branch library -- multilingual, multicultural, and intergenerational. When Santos learned through a friend at the Seattle City Council that Metro was about to sell the property, he went to work.

"I had to lobby two federal departments, get the cooperation of two U.S. senators, one a Republican, and 39-40 members of the Metro Council" (Chesley interview). The groundbreaking ceremony for the $45 million complex was held August 29, 1995, six years after the process began.

Tapped by the Top

In 1994 -- Santos's network now stretching from the Panama Hotel Tea Room to City Hall, Olympia, and beyond -- his life took another sharp turn. Henry Cisneros (b. 1947), the director of HUD in the Clinton administration, tapped Santos to be his Northwest/Alaska region representative and to oversee 400 employees in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Alaska.

"Working in the ID was quite a comfort zone and I was going to the other side," Santos recalled (Chesley interview). In that position he opened downtown Seattle's Federal Building to the city's homeless, retrofitted cargo containers for migrant-worker housing, and generally enjoyed his tenure. "The easiest job in the world," he said.

But a standoff during the World Trade Organization (WTO) clashes in November 1999 would test all of his negotiating skills.

Crisis Management

During the WTO meetings in Seattle, a group of about 150 anarchists occupied a vacant apartment building at 9th Avenue and Virginia Street, demanding that the building be converted to a homeless shelter after the WTO meetings ended. They had been warned that members of the police tactical squad were ready to storm the building.

Santos was called in to negotiate and he met with the police, city officials, the anarchists, and an angry owner, Wah Lui, who was nonetheless willing to talk with SHARE/WHEEL, a homeless advocacy group. The anarchists walked out of the building with Santos. A facility with 94 units of transitional housing at Sand Point was named Santos Place in his honor.

Santos's efforts, although good for the community, were hard on his marriage, and he and his wife, Anita, divorced in 1981. He was married briefly to Nina Sullivan, "on the rebound," he said (Chesley interview). Then in 1992 he married Sharon Tomiko, whom he met while working on Lowry's campaign for the state Senate.

Tomiko, an activist involved in international women's issues, was a delegate to the 1995 International Women's Conference in Beijing, China. In 1998 she was elected to the Washington State House of Representatives. She was re-elected several times and was Majority Whip.

Lasting Legacy

When the presidency of Bill Clinton (b. 1946) ended in 2001, so did Santos's HUD position, and he returned to Inter*Im. Santos retired in March 2006, but not really. He remained on retainer, gave tours, lectured to high-school and college students, and helped with fundraising.

Santos had developed a modest before-and-after slide show about the Kingdome controversy, and over the years it evolved into a full-blown production, "Uncle Bob's Neighborhood." He wrote that "the sound of people clapping was addictive" (Santos, 120). Indeed, Santos always had charisma. "[S]aid Washington Mutual public affairs executive Tim Otani, who met Santos as a student activist in the '70s, 'I was quite taken by that as a student, how someone could be so passionate about a community's needs'" (Beason).

During Santos's tenure at Inter*Im, some 1,000 residential units were added to the International District. And in his memoir, Hum Bows, Not Hot Dogs, Santos acknowledged the hundreds of other International District activists, of all ethnic backgrounds, who joined in the neighborhood's various struggles.

On December 1, 2005, in Washington, D.C., Partners for Livable Communities honored Santos, Gossett, Maestas, and Whitebear (posthumously) with a Bridge Builders Award "for building and fostering a coalition of minority leaders who work together to best advocate for King County, Washington's diverse population." In 2006, the Seattle City Council honored Santos for his work with Inter*Im.

Bob Santos died in August 2016 at the age of 82.