On May 9, 1812, the ship Beaver, commissioned by John Jacob Astor, reaches the Columbia River, bringing supplies and reinforcements for the Pacific Fur Company, whose charter members had established a fur post called Astoria near the mouth of the Columbia the previous year. Watching the approach of the ship from shore, several Astorians climb Cape Disappointment and set trees on fire to serve as an impromptu lighthouse. Among five newly hired clerks on the Beaver are Ross Cox and Alfred Seton, who will record first-hand accounts of activities in the Columbia district.

Astor's Ambitious Plan

During September, 1811, John Jacob Astor (1763-1848), New York merchant and principal owner of the Pacific Fur Company, was busily preparing to send a ship to the Northwest coast. One year earlier, he had launched an ambitious plan to establish an American trading network across the continent. He had dispatched two expeditions -- one by sea and one by land -- to scout the territory and build a post near the mouth of the Columbia River. Although he had heard nothing of the fate of either party, he was moving ahead with his original plan, which called for a second ship to resupply the new post in the summer of 1812.

For this important mission, Astor chose the Beaver, whose ownership he shared with three other merchants. Built six years earlier specifically for trade with Canton, she was fast and reliable, a "full flat bottomed ship of 427 tons, with capacity for 1,100 tons of cargo, and a live oak frame" (Porter 138). To captain the vessel, he hired Cornelius Sowle (1769-1818), a Rhode Island native who had made at least two trips around Cape Horn and across the Pacific to China.

In addition to trade goods and other necessities, Astor was sending two-dozen reinforcements to aid his Pacific partners in expanding their trading operations. On October 8, he signed Articles of Agreement with 15 clerks and artisans who agreed to "direct well and faithfully and to the best of their Skill and ability for the full term and time of five Years" and to "promote the Interests and execute the lawful Commands of the said Company" (Porter, 476). Their salaries ranged from $100 to $300 a year, with a guarantee of transportation back to New York at the end of five years "if the State of things upon the said North West Coast renders it practicable" (Porter, 477). John Clarke (1781–1852), a recent partner in the venture who may have been a distant relation of Astor, had charge of the fresh recruits during the voyage. Thirty years old, Clarke had clerked for six years with the North West Company in Canada before traveling south to join the competition.

The Clerks

Among five new clerks hired by Astor, Ross Cox (1793-1853), an 18-year-old Irish immigrant, described himself as "captivated with the love of novelty, and the hope of speedily realizing an independence in the supposed El Dorado" (Cox, 12). Historians Edgar and Jane Stewart observe that Cox was either "exceedingly eager to accompany the expedition or his qualifications were not too highly thought of" (Cox, p. Intro., xxx), for he would earn only $100 a year while his fellow clerks earned at least $150 annually.

Alfred Seton (1793-1859), the best-paid of those clerks (with a salary of $200), was exactly Cox's age, and had grown up in a privileged New York mercantile family whose circumstances had been reduced by economic difficulties. Seton, who had recently finished his second year at Columbia College, later admitted that he had acquired expensive habits in the city, and "if I had remained I would have found myself overwhelmed with debts, in bad Company, & with little hopes of raising myself to a respectable situation of life" (Seton, 130). Shortly after boarding the Beaver, he produced a seven-by-nine-inch cardboard-bound copybook and began a journal of "the little occurrences that happened" in the hope that in the future he would be able "to peruse these lines & call to mind the sensations" he had experienced (Seton, 29).

A relatively uneventful voyage around Cape Horn was marred only by the loss of two seamen washed overboard in a storm, one death of scurvy, and occasional friction among Astor's clerks, as related by Seton: "Here, then are six Young Men pretty nearly the same age, & all pretty violent in their tempers, confined together in a ship for six months. It would be strange indeed if there was not sometimes some disputes, between one or the other" (Seton, 34). But when they caught sight of Hawaii in late March, 1812, "all hands in the ship were in the greatest good humor & all former disputes & miffs were forgiven and forgot" (Seton, 70).

At anchor in Waikiki, the captain engaged 26 Hawaiians -- 16 for the company's service, 10 for his ship -- and agreed to pay each man "$10 a month & a new suit of clothes each year. Before weighing anchor on April 6, the crew loaded 60 hogs for the colony at Astoria, along with "two boats full of sugar cane to feed them, and some thousand cocoa-nuts" (Cox, 45).

The Fate of the Tonquin

While visiting shore, the Americans met an English expatriate who gave them a "melancholy acct. of the Tonquins being cut off on the NW coast by the Ind[ians] & her being blown up" (Seton, 71). (The Tonquin had sailed from New York in September 1810 with half the leaders of the Pacific Fur Company on board, aiming to establish a trading post near the mouth of the Columbia). The Englishman had heard this report from a sea captain who had been trading along the Northwest coast, but had no further details regarding the location of the attack or the number of survivors. Although the report of her destruction proved true, the Tonquin had fortunately deposited most of the Pacific Fur Company employees on the lower Columbia before coasting north to trade. For the men aboard the Beaver, "this acct. was [truly dis]tressing to us, for our success depends in great measure, upon the Gentlemen of the Tonquin, for they were pitched upon as the most competent to erect the first settlement & they carried aboard their ship the principal means, by which the settlement was to succeed" (Seton, 71). The rumor of the loss of the Tonquin cast a pall of anxiety over the rest of the voyage.

On May 6, 1812, the Beaver "had the happiness of beholding the entrance of the long-wished-for Columbia" (Cox, 47). Captain Sowle fired signal guns to alert the Astorians of his arrival, but received no answer. The men on board were "very much dejected at the non-appearance of the Gentlemen of the Tonquin" (Seton, 84), and their trepidations about the fate of their compatriots mounted.

The captain stood off and on the bar in light winds the next day, firing more signals at regular intervals, with "all eyes & ears looking & listening for some reply, but in vain; after waiting half an hour the ship stood offshore again" (Seton, 84). On May 8, Sowle dispatched a small boat to sound the channel and put out buoys to guide his course across the bar. Around midmorning, the men aboard ship "were delighted with hearing the report of three cannon from the shore in answer to ours" (Cox, 47). Seton recorded that "this cheered our spirits a little; but still they might be the muskets from the boat. At 11 the boat came along side & the first question they asked us was, whether we had heard six guns? & that they had heard three heavy & three smaller ones very distinctly; this confirmation of our hopes as may be supposed, made us feel happy, & orders were immediately given to answer with two guns, which was done" (Seton, 85). Later in the afternoon, a white flag was sighted atop Cape Disappointment, giving a further lift to their spirits. The first mate urged the captain to run the bar, but Sowle chose to wait for morning and another sounding.

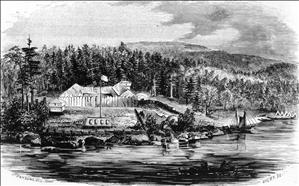

Meanwhile, the Pacific Fur Company officers at the newly established Fort Astoria (near present-day Astoria, Oregon) had sighted sails off the mouth of the river, "going to and fro from Cape Disappointment to Point Adams. She fired three guns, which we answered with as many. We expected to see her come in with the evening flood Tide but were disappointed" (Jones, 88). Duncan McDougall (178?–1818), the partner in charge of the post, inferred from the delay that the captain seemed "to be in expectation of our sending out a pilot" to guide him across the bar. McDougall and seven of his men crossed the Columbia to a Chinook village to "try to prevail on some Indians to go out to the vessel if she neared the river, or if this was impracticable to make them signals" (Jones, 88). With evening approaching, they climbed Cape Disappointment and "set fire to several trees to serve in lieu of a lighthouse" (Cox, 48).

The next morning, May 9, the first officer again set out to sound the channel. Around 8 a.m., an Indian canoe was seen heading for the ship, followed by a type of barge. "Various were the hopes and fears by which we were agitated, as we waited in anxious expectation," recalled Ross Cox, who described the ensuing scene in his memoirs:

"The canoe arrived first alongside. In it was an old Indian, blind of an eye, who appeared to be a chief, with six others, nearly naked ... . The only intelligence we could obtain from them was, that the people in the barge were white like ourselves, and had a house on shore" (Cox, 48).

The one-eyed chief was the well-known Comcomly (?-1830) of the Chinook tribe, who was well acquainted with the treacherous waters of the Columbia bar.

The Delightful, Inexpressible Pleasure...

A few minutes later the barge (probably a dory) came alongside, "and we had the delightful, the inexpressible pleasure of shaking hands with Messrs. Duncan McDougall and Donald M'Lennan, the former a partner, the latter a clerk of the Company, with eight Canadian boatmen" (Cox, 48). McDougall, one of the Pacific Fur Company partners who had come out on the Tonquin to found Astoria, reported that all was well at the post and that most of the party who had traveled overland from St. Louis with Wilson Price Hunt had arrived safely. McDougall had also received a news of the Tonquin's destruction after it had departed the Columbia the previous year, and had concluded that the report was credible when the ship did not return as scheduled to pick up furs and deliver more cargo.

Donald McLennon, (sometimes spelled McLennan) one of the clerks who had arrived with McDougall, joined the Beaver's first mate in the ship's boat and "took charge of the ship as pilot; and at half-past two p.m. we crossed the bar, on which we struck twice without sustaining any injury" (Cox, 49).

Books, Soap, Wine, and Bales of Cotton

The Beaver dropped anchor in Bakers Bay, in the lee of Cape Disappointment on the north side of the Columbia. Fort Astoria lay across the river and several miles upstream, and after examining the situation, Captain Sowle pronounced the channel too shallow to risk a crossing. For the next 10 days, small boats ferried more than $30,000 worth of cargo from the ship to the post. The first order of business was unloading the livestock: "3 She & he Goats, 2 fowls, viz. Hens, 2 Geese, and 2 ducks" in addition to the hogs from Hawaii (Jones, 88).

Among the post supplies that emerged from the hold were carpentry tools; a blacksmith's forge and bellows; muskets and bayonets; rice, molasses, and coffee; a military drum and two fifes; a crate a dishes with "fancy bowls" and an enameled tea pot; two boxes of "segars" [ cigars]; casks of rum, gin, Madeira wine, ale, and whiskey; 500 pounds of soap; seeds of onions, turnips, carrots, radishes, muskmelon, and four types of cabbage. One box held two dozen books, from Barrett's Spanish Dictionary and a four-volume Life of Bonaparte to The Scottish Chiefs and Tales of Fashionable Life.

The new assortment of trade goods included several hogsheads of tobacco; bales of cotton and woolen cloth; 500 fish hooks; 15 dozen pails; 800 pounds of beads; a 109 men's felt hats; and eight bales of handkerchiefs. After being sorted and inventoried in the storerooms at Fort Astoria, many of these trade items were repacked for shipment upstream.

On June 29, a large party set off in 10 canoes and two bateaus, headed up the Columbia to various destinations in the interior. One contingent, including clerk Alfred Seton, would search for a suitable trading site on the Snake River; a second party would restock the company's post at Fort Okanogan; a third group, under the command of John Clarke, would establish a new trade house on the Spokane River to compete with the North West Company of Canada's Spokane House.

Back in Bakers Bay, Captain Sowle prepared to set sail on a trading voyage along the Northwest Coast and a visit to the Russian-American Fur Company in New Archangel (Alaska). Wilson Price Hunt decided to go along to survey the commercial potential of the areas further north. After a 30-day wait for a favorable wind to cross the bar, the Beaver departed the Columbia on August 3, planning to return two months later to pick up the company's furs for delivery to Canton.