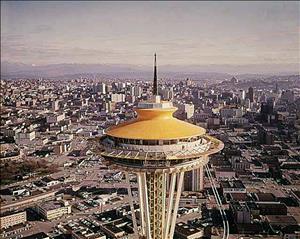

On September 20, 1962, a flock of homing pigeons is released from the observation deck of the Space Needle as part of a plan to publicize the 1962 Seattle World's Fair. The birds, sponsored by many of Seattle's media personalities, race their way back to Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota, after making an unplanned pit stop in downtown Seattle. Very few of them are reported to have arrived home.

Winging It

During the waning days of the Century 21 Exposition, fair officials sought ways to bring attention to the fair, hoping to draw more people before the fair closed on October 21, 1962. One of the strangest publicity stunts was the World's Fair Unlimited Pigeon Rally, which involved a flock of homing pigeons released from atop the Space Needle and their cross-country flight to their home base of Minneapolis-St. Paul, Minnesota. The rally was co-sponsored by the Twin Cities Pigeon Fanciers Association and the Microfilm Products division of the Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company. Twenty-four pigeons would be banded with microfilm. The race was billed as a commemoration of the 92nd anniversary of "air-mail," dating back to when pigeons carried microfilm during the Siege of Paris in 1870.

To ensure ample amounts of press, each pigeon was sponsored by a Seattle-area newsman, radio disc jockey, or television personality, including such local luminaries as Jack Jarvis (1913-1972) and Emmett Watson (1918-2001) from the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, John Reddin (d. 1976) and Lenny Anderson (1921-2000) from The Seattle Times, and KING radio's Frosty Fowler. Each bird was given the name of its sponsor, who would win a bronze trophy if his pigeon won the race.

Dick Larson, a Seattle-based airline pilot and member of the Century 21 Pigeon Racing Club, arranged to have the pigeons flown in by jet from Minneapolis, so that they would be well rested for their 1,225-mile race back home. The day before their return trip, a female "course steward" was released from Woodland Park Zoo, the home of Geronimo, the last surviving pigeon veteran of World War II. The male pigeons would hopefully seek out and follow the steward, vying for her attention.

At 9 a.m. on September 20, the pigeons, their sponsors, race officials, and fair staffers gathered on the observation deck of the Space Needle to start the rally. Assisting in their efforts -- and also providing eye candy for the predominantly male crowd -- was Christa Speck (1942-2013), dubbed "Miss Pigeon Rally." Speck was a hostess for Sid (b. 1929) and Marty (b. 1937) Krofft's "Le Poupees de Paris," a risqué marionette revue that performed at the fair's adults-only Show Street venue. She was also Playboy magazine's Playmate of the Month in September 1961, and would later be chosen as the magazine's 1962 Playmate of the Year.

The men gathered around the young woman, rapt in attention -- not unlike their homing pigeon counterparts in the race. Speck dazzled her audience by sprinkling a little birdseed into her bodice and letting some of the pigeons roost on her shoulders to retrieve the seeds from her cleavage. This eye-popping part of the rally did not make its way into the newspapers.

And They're Off

Standing by for the race were 51 pigeons, more than twice the number that had been originally planned. Each sponsor was given the opportunity to name a second bird, leaving three with only the number marked on their leg bands. Jarvis -- hoping to "keep in good with certain young women who work at the fair" -- named his second bird "Georgia Barbara Marianne Frances Joyce Charlotte Sally Connie Penny Dorothy Gloria Betty Sherry Elaine Eve Lola Joanne Nicky Judy Maralyn."

Some of the officials made a few short speeches while Miss Pigeon Rally poured ample amounts of champagne for the guests. Among the imbibers was one gent who had wandered out of the Eye of the Needle restaurant right into the festivities. He obviously had a good time and exclaimed, "I've had five glasses of champagne, and I don’t even belong here. Does this happen every morning?"

The race was supposed to commence at 9:15, but there was still plenty of champagne to drink, so the rally didn't begin until 9:48. At a given signal, Speck and Al Rochester (1895-1989), executive director of the State World's Fair Commission, flung open the cages and the crowd cheered as the pigeons took to the skies. The birds circled once around the Space Needle, but instead of flying toward Minneapolis they headed straight for Pioneer Square, less than a mile away.

Somewhat chagrined, a group of pigeon fanciers rushed downtown to shoo the pigeons on their way, but by the time the men they got there, the birds had regained their sense of direction and continued their long journey eastward.

A Wing and a Prayer

All that was left now was a long wait to see which bird won the race. The flight was expected to take only three to six days, but after a week, none of pigeons had made their way home. Some folks worried that the long climbs over both the Cascades and Rockies had tuckered them out. Finally on September 28, one showed up in Minneapolis at the home of Rudy Lang, its owner. Lang received a model of the Space Needle as a prize.

Unfortunately for fair publicists, the pigeon was one of the three that had no sponsor, so the press had to report that the winner was RAM 4665 -- not the most exciting of news. Rally officials decided to wait and see which sponsored bird turned up next, so that a trophy could be given to one of Seattle's media personalities. It turned out to be Frosty Fowler's bird, but the pigeon didn't make it all the way home. The poor feathered "Frosty" had been shot by a hunter in South Dakota.

Finally, on October 6, a second bird arrived in Minneapolis. It was sponsored by KVI disc jockey Dave Clarke, but by this time interest in the race had all but vanished from the newspapers. The only mention of Clarke's "win" was buried in one of Jarvis's columns for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Whether any of the other birds finished the race is unknown, but Jarvis suspected that his two birds probably went south for the winter.