Patos Island in San Juan County is the northernmost of the San Juan Islands and is known for its remoteness and beauty. A small light station became operational there in 1893, and a 38-foot tower was added to the building in 1908. The island, its lighthouse, and one of its better-known keepers, Edward Durgan, were immortalized in a 1951 book, The Light on the Island, written by Durgan's daughter Helene Durgan Glidden (1900-1989). Automation arrived at the lighthouse in 1974 and it was abandoned, leading to its eventual deterioration. The lighthouse was restored in 2008 and 2009, and since then tours have been offered on many summer weekends.

Patos Island and its Lighthouse

Patos Island was named by Spanish explorers passing through the area in 1791 and 1792. Patos, the Spanish word for ducks, got its name from either the island's ducks or possibly from a prominent rock formation resembling a duck found on the eastern side of the island. The small island encompasses 207 acres, and from Bellingham is a boat trip of about 25 miles. The northernmost of the San Juan Islands, it lies fewer than two miles east of the Canadian boundary in the Strait of Georgia. Because of this proximity, Patos Island's coves and caves have long been a favorite for smugglers bringing in contraband from Canada -- Chinese laborers in the nineteenth century, alcohol during the Prohibition years of the early twentieth century, and marijuana later in the twentieth century.

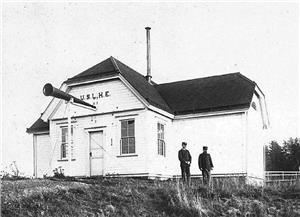

In 1893 the U.S. Lighthouse Board established a lighthouse at Patos Island, located at Alden Point on the island's northwestern tip. A large, attractive, two-story house was built nearby to house the lightkeepers and their families. Initially the little station was simply a red light atop a post, along with a third-class Daboll trumpet fog signal housed in a small one-story building. However, both the fog signal and the light proved deficient. The fog signal's trumpet was replaced in 1894, but the light stayed for 15 years despite complaints and requests for a flashing light. In 1908 a 38-foot tower (with a balcony) was added to the lighthouse in order to house a new light with a revolving lens that flashed a white light every five seconds. The new light was a fourth-order Fresnel lens originally illuminated by oil-burning wicks and turned by a combination of weights and chains, much like some of the larger clocks of the day.

Early Lightkeepers

Washington's lighthouses usually had two keepers in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and Patos Island was no exception. When its lighthouse became operational in 1893, the keeper's salary was $700 a year (about $17,600 in 2012 dollars). The assistant keeper received $500 annually (about $12,600 in 2012 dollars). The first keeper, Harry Mahler (1865-1935), reported for duty on August 2, 1893, and remained on the island almost exactly 10 years. Mahler had begun his career as a lightkeeper five years earlier at the New Dungeness Lighthouse in Clallam County, and after his stint at Patos Island served four years at Cape Meares in Oregon before returning to staff lighthouses in Washington. In 1917 he was interviewed by The Seattle Times while serving at the Alki Point Lighthouse, and described his philosophy on lighthouse life that was likely shared by many of his fellow keepers (a number of whom served for decades): "Whenever a lighthouse keeper is mentioned the adjective 'lonely' is always invoked. But they are all wrong. It's not a lonely life from my viewpoint" ("Keeper of Light ...").

Mahler's assistant keeper, Edward Durgan (1858-1919), reported for duty at Patos Island on July 28, 1893, and though he served only a little more than 10 months in his first stint there, he later become intimately associated with the island's early history. In 1895, the year after he left Patos Island, Durgan began serving at the Turn Point Lighthouse on Stuart Island in San Juan County. It was there, in February 1897, that he and his assistant Peter Christiansen rescued the crew of a tugboat that had run aground on the island, as well as the occupants of the barge under tow that was adrift nearby. Many of the boats' crew members were drunk, and one of them lost his wits and threatened the rescuers with a butcher knife. He had to be forcibly restrained and was chained and banished to the lighthouse's henhouse until he sobered up. For their efforts, Durgan and Christiansen received a letter of commendation from the U.S. Navy.

Durgan next served at the Coquille and Heceta Head lighthouses in Oregon before returning to Washington in 1900, where he served at the New Dungeness Lighthouse. In December 1905 he returned to Patos Island as lighthouse keeper, accompanied by his wife and many of his children, one of whom later died on the island. He served as keeper on Patos Island until February 1911, and his daughter Helene Durgan Glidden later wrote a book about the family's experiences there called The Light on the Island. A blend of fact and fiction, the book is a fascinating account of life on the remote island in the early twentieth century and has left a profound impression on many a reader.

In 1911 Durgan transferred to the Semiahmoo Lighthouse near Blaine in Whatcom County, where he served as keeper for eight years before dying in March 1919 of a heart attack while on duty. His wife, Estelle (ca. 1866-1943), who was with him when he died and serving as his assistant keeper (one of only three women keepers serving on the Pacific coast in 1919), replaced him for a time. In his day Durgan was one of the better-known lightkeepers of the Northwest, and a century later is still remembered.

Lonely Perils

If there was any kind of emergency on the island in the early years of the lighthouse, the keeper could only signal for help by flying the station's American flag upside down. Even then, passing boats and ships didn't always notice. (Telephone service arrived on Patos in 1919 and took care of that problem.) And if the keeper needed supplies -- or even just needed to get his mail -- a boat trip was the only way to go. One of the closest places (at least on American soil) was Eastsound on Orcas Island, about five miles away. The lighthouse's nearest neighbor was actually in Canada, at the East Point Lighthouse on Saturna Island, a little more than three miles to the west.

These boat trips could be risky, especially in bad weather. One story underscores this risk. In 1909 Noah Clark began working with Durgan at Patos Island as assistant keeper. Clark and Durgan already knew each other well; in 1904 Clark had married Durgan's daughter Mary. On December 23, 1911, Clark motored over to Blaine to pick up Mary and their young son, who had been there visiting the Durgans. On the return trip their boat's motor failed as it approached Patos Island and the boat began to fill with water. It was dark and stormy, but nonetheless Clark jumped overboard to swim to shore for a rowboat to save his family. He was never seen again. His family (including another one of Durgan's daughters, Estelle, who had joined the Clarks for the return trip), drifted in the water that night and part of the next day, later having to crawl on top of the boat's cabin when it filled further with water. They eventually grounded on a shoal and were rescued.

A Snapshot From 1958

With the exception of some informal tourism during the summer months, the lighthouse remained an isolated outpost well into the twentieth century. This was especially true in the winter, when the island often went for months without a visitor. Ships periodically ran aground on the island, and a radio beacon was installed at the station in 1937 to further aid navigation. Lighthouse keepers came and went, but most seem to have appreciated the island's solitude. A 1958 article in The Seattle Times Sunday Pictorial (precursor to Pacific Northwest magazine) said the lightkeepers -- by this time called "coastguardsmen" since the lighthouse had been under the domain of the U.S. Coast Guard since 1939 -- and their families didn't seem to mind the solitude much, pointing out that they often skipped the 72-hour liberty granted every third week so they could stay on the island for months at a time.

By 1958 other changes had come to the island. The lighthouse's light was now electrical, powered by a generator. The station's fog signal and radio beacon were synchronized to aid in distance finding. Until the previous year the Patos Island Lighthouse had made hourly radio checks with the Smith Island Lighthouse in Island County to the south, and stopped only because the lighthouse on Smith Island was abandoned in 1957 due to encroaching shoreline erosion. (It eventually tumbled into the Strait of Juan de Fuca.) If Patos Island's radio was silent for four hours, Smith Island would notify the Coast Guard base in Seattle, which could have a helicopter dispatched from Port Angeles and on the ground at Patos within an hour and 20 minutes. And by 1958 it was no longer necessary for the coastguardsmen to go to Eastsound or Bellingham for supplies or mail; Coast Guard patrol boats operating out of Bellingham brought those to them twice a week. That same year the original keeper's house was torn down and replaced with a duplex to house four coastguardsmen and their families.

In 1974, the federal Bureau of Land Management leased Patos Island to the Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission, and the island has been a marine state park since then. In June of that year the light was automated -- a white light now flashed every six seconds, with a red panel indicating dangerous shoals -- and it was no longer necessary to staff the lighthouse. A few people visited the facility initially, but that quickly faded. The lighthouse was abandoned and soon fell prey to vandals and the elements.

Restoration

By the 1980s both the lighthouse and the housing duplex were in disrepair. The lighthouse's fourth-order Fresnel lens was found to have been damaged and was removed, ending up in private ownership in Oregon. In 2005 the Bureau of Land Management contracted with the Orcas Island Fire Department to tear down the old Coast Guard duplex, leaving only the original lighthouse building and tower still standing.

In 2007 a nonprofit, Keepers of the Patos Light, was organized by two childhood friends, Linda Hudson of Lopez Island and Carla Chalker of Wisconsin, with the goal of restoring the lighthouse and preserving the island's natural scenery. The following year the lighthouse was indeed renovated by the Bureau of Land Management. Its foundation and tower were repaired, and a fresh coat of paint, a new roof, new doors, and windows were added. Further improvements were made to the site in 2009, enabling the lighthouse to be opened to the public for tours that summer for the first time in more than 25 years.

Life on Patos Island deeply resonated with many who lived there and served in its lighthouse. Perhaps as a reflection of this, departing coastguardsman Clifford D. Thresher left a poignant goodbye (a variation of a Sanskrit proverb) in the lighthouse's visitors register on June 24, 1974, when the station was automated: "Mr. and Mrs. Clifford D. Thresher departed this unit after 9 months duty. One last thought before I go. Yesterday is already a dream, and tomorrow is only a vision. But each today well lived, makes every yesterday a dream of beauty, and every tomorrow a vision of hope. Automation is now in progress" ("History").