For most young men who reached their late teens in the late 1960s, mandatory military service was a looming reality. At the other end of the fun spectrum were the early rock festivals, which, for a time, were another rite of passage, at least for members of the "counterculture" and for the curious. In this People's History, Dale Eldon Lund recalls his experiences with both, along with some other adventures and misadventures of youth. This account first appeared on Dale's blog, the Rum Butter Cartoon (http://oldelephantwings.blogspot.com/) and is reprinted by permission.

You're In the Army Now

I had graduated from high school in Sultan -- the Class of '67 -- only about 30 students strong. My parents gave me a portable TV and a suitcase for graduation gifts. I took the hint, subconsciously, and journeyed off to Libby, Montana, to seek my independence as a maintenance man at the St. Regis lumber mill. The working conditions were terrible and I was back home in a month, the last words from the man who hired me being, "I'm sorry we wasted our time with you." So I enlisted in the United States Coast Guard, took its battery of tests and waited through its six-month waiting list. But on the day I was supposed to report in and take my oath of service, I instead took off on a six-month hitchhiking trip around the U.S. My parents told me that the Coast Guard was not happy. But still unsure about what to do when I returned home to Sultan, I joined the United States Army, and actually did show up on May 2, 1968, surprised to find out that the sergeant who was welcoming us to basic training with an impersonation of Sergeant Carter on "Gomer Pyle," wasn't impersonating.

I was in trouble right off in the army. We unfortunates were standing in a haphazard formation, still in our civilian clothes, while the roster guide, a sergeant, was yelling at each of us and sounding just like Sergeant Carter. I laughed at the joke. So he came up to me, yelling at me about my laughing, nose-to-nose just like Sergeant Carter, and then I really laughed. He was funny. Great impersonation. But he was dead serious, and it didn't help my case a bit when the second-lieutenant then yelled at me and asked me some question and I responded with, "Yes, sergeant!" Those silver bars on the uniform shoulders were not commonplace in Sultan, Washington.

And so I hated the army from the outset. When I found they were serious about their impersonations, I was amazed. My father was a Methodist minister, a kind man, and my mother doted on me. My siblings, all older, were upset that I was so spoiled. And now I had men yelling orders at me, watched a sergeant kick a basic trainee in the head because the poor guy wasn't crawling fast enough, watched another G.I. follow orders by walking down the formation with his penis hanging out of his fly while all the guys he passed followed orders by saying, "Hello, Richard" (Dick), and I watched a Kentuckian be loudly ridiculed in the mess hall for having no teeth and forced to walk around all of us with a big toothless smile, and later, when he actually got dentures and was so proud, was loudly ridiculed in the same place by the same men and forced to walk around all of us clacking his new teeth together. The army was inhuman. And then came the forced march.

This was when I began hating rain gear. Basic training was at Fort Lewis, Washington, and I was, as long as I can remember, a native of Washington, unlike the sergeants making us take the 13-mile march in full backpack and carrying M-14 rifles. It was a usual day of occasional rain showers, but a warm day and we were hot from the hike. Every time the rain would start, we'd be ordered to put on our rain gear, which involved a lot of awkwardness. Marching in this rubberized stuff was stifling, and when the shower would soon end and the clouds uncover the sun, the sergeants were in no hurry to make us take the rain gear back off, and my sweat made me wetter than the rain would have. Ever since the army, I've never used rain gear; and during my 22 years with the Postal Service, even here in the Midwest where the rains are often torrential, I don't even own rain gear.

A Brief Escape

But I didn't mean to talk about rain gear. I meant to talk about what I saw on the forced march. I saw a road. Along the 13-mile trail, the 200 of us crossed an empty, paved road -- a civilian road -- a road to freedom. I couldn't get the sight of it out of my head. And that night, back on the second floor of the barracks full of exhausted and heavily sleeping G.I.'s, I quietly got out of my bunk and opened my locker, put on my olive-drab fatigues, climbed down the fire escape ladder, and took off. Two guys on guard duty spotted me and yelled out for me to stop, and I ran, heading toward the beginning of the forced march trail. And by the time I got up the hill to the trail going into the woods, my barracks lights were on, the outdoor lights were on and I could hear the commotion. The prisoner had escaped!

While the legs and feet of everyone in the platoon ached from that day, I repeated the forced march that night, following the trail by moonlight. Eventually I was too sleepy to keep going, and I lay down on the damp forest floor, and slept. It was dawn when I awoke and continued on, finally reaching that beautiful road to freedom. But this time I didn't cross it. I followed it. On and on I wandered, passing through a Girl Scout camp, where I got a lot of stares, and finally reached the I-5 freeway, where I hitchhiked north into Tacoma, heading towards Canada.

It was against regulation to be off post in fatigues, and I kicked myself for not having put on my khaki dress uniform instead. I knew that, in this olive-drab get-up I would be caught, and so I walked down alleys in Tacoma, hoping to find some civilian clothes hanging on a line to change into. At one point, a man, probably a military man who knew the score, even told me I should go back. He was probably the one who reported me. For soon after, when walking out of a gas station after buying a bottle of pop, an M.P. car pulled up in front of me and I was expeditiously arrested.

The police were surprisingly nice to me, except for one point, when, while waiting on a folding chair I fell asleep. Apparently some cop tried to order me awake and I didn't wake up, so he forcefully pulled me out of the chair by my arm and threw me across the room, and I awoke just in time to keep my face from hitting the hard floor. When I got back to my company, I was forced the first night to sleep on the floor in the "orderly room" -- the company headquarters. And while lying there, my drill sergeant came and stood over me, snidely welcoming me back.

This attempted desertion from the U.S. Army was perhaps the best thing I did throughout my three year's in the service. Because I was caught the next morning, I was charged with A.W.O.L. instead of desertion, and given, as punishment, an Article 15, which consists of restriction, a fine, and extra duty. Well, in basic training, we're already restricted to the area, and so that was irrelevant. The fine they never took. And instead of extra duty, I got less! As a matter of fact, from then on, they left me alone almost as if I were invisible, for fear of my taking off again, which causes a lot of tedious paperwork they wanted to avoid. So after my escapade, I watched guys being virtually tortured while I was passed over.

Sky River

I had surgery at the end of basic training, which threw everything out of schedule and I wound up being a "hold-over" at Fort Lewis. My company (D-3-1) was now practically a ghost town, with only a skeleton crew of sergeants and a few disoriented G.I.'s. There were only three or four of us staying in a building next to my old barracks. We had nothing to do but await orders to some unforeseen assignment, and I became fairly good at pool and an expert in shooting rubber-bands. I could (and still can) shoot a cigarette out of a guy's mouth across the room. (They hated that.) Finally I was given orders to go to Sandia Air Force Base at Albuquerque, New Mexico; but, before that, I was given my first leave, and I went home to Sultan. I had no idea what else was coming to Sultan.

Sultan then had a population of 960, situated where the Sultan River runs into the Skykomish River and becomes the Snohomish River, winding its way through Snohomish County all the way to Everett and into Puget Sound. Sultan was a comfy little town, and Dale's Market and Smith's Bakery were still in business. I have yet to find any Danishes better than those at Smith's Bakery. My Dad's church was on the corner of 3rd and Birch streets, and our house was across the parking lot, on the corner of 2nd and Birch streets. Many loggers lived in the town, and up on 1st Street there was a school of forestry.

I had a white 80cc Yamaha motorcycle (a lemon of a bike), and one of my favorite things to do was to ride through the high stalks in Latimer's corn field south of town, going fast and not seeing where I was going. I had had a newspaper route in Sultan. I covered half the town and Calvin Vos covered the other half, and we rolled the newspapers beforehand at the bench in front of Dale's Market on the quiet main street, which ran parallel to Highway 2. But other than riding my little motorcycle, visiting with Calvin at their dairy farm (located in town!), and sneaking into the nudist camp up the Sultan Basin Road, there wasn't much to do. But then, during my first leave home from the army, 20,000 hippies came to town.

It was over 40 years ago, Labor Day weekend, 1968, and we got word that there was to be a rock festival at Betty Nelson's raspberry farm south of town, not far from Latimer's place. I knew of no street drugs in Sultan, hippies were a phenomenon featured in Life magazine and confined to such places as San Francisco and New York City, and no one really knew what a rock festival was. Woodstock wasn't until a year later. I knew Betty Nelson, but not well, and went to school with her daughter, a freshman while I was a senior, but at least we were in study hall together. Her daughter always struck me as a quiet conservative girl. But Betty told the reporters that she had always wanted to take her kids to a Beatles concert, and that this would probably be as close as she could get. That weekend, middle-aged, brunette Betty Nelson became the "Universal Mother," also known as "Ma Kahoona" at least to locals.

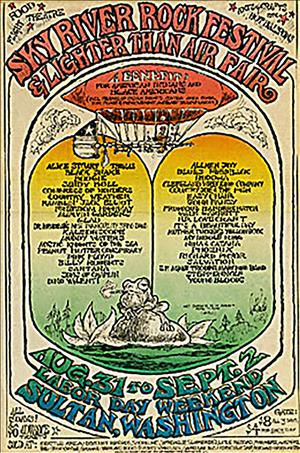

It was the Sky River Rock Festival and Lighter Than Air Fair. The population of Sultan suddenly increased 20 times its size, with people we had never seen the likes of before in person. Harley choppers lined the curbs for a block in front of Dale's Market, and children ran naked down the sidewalk. Flowered VW buses and old cars full of hairy heads were rampant, leaving in their wake an unfamiliar odor like burning grass. Nude couples could occasionally be seen bobbing in the high grass of a roadside field. There were so many people attending the event that the road going past Betty Nelson's farm was turned into one-way, and people were parking as far away as Everett (25 miles) and taking shuttle buses to the festival. The State Patrol was directing traffic. It was bizarre!

Dad stayed pretty much in his study at church, and Mom stayed at home, not wanting to venture out during this craziness. But Mom was very curious and enjoyed my venturing out and coming back to tell her about it all. I was caught up in the excitement, and wanted to pass myself off as a hippie and attend the Festival, but this was difficult with a military haircut. So I decided to give in to it rather than hide it. I put on my brown corduroy jacket that I had hitchhiked around the U.S. in, pinned my Dad's old army major leafs on my shoulders, donned a medallion and some strings of beads, put on my [...] cap and dark glasses, got on my 80cc Yamaha, and rode to the Sky River Rock Festival.

I looked as goofy as it sounds, but no one laughed at me. I was completely accepted wherever I went by these strange visitors. Non-conformity was cool. As I rode south of town toward Nelson's farm, I'd pass a car packed full of people and give them the peace sign, and a dozen hands would stretch out of the windows enthusiastically returning the gesture. It cost $8 at the gate to get into Sky River, but somewhere along the line I learned that there was an unguarded trail going right into the farm, and so I could enter the event any time I wanted for free.

I was a square. It was a big thing for me to buy a Monkees album not long before, and I wasn't familiar with many rock groups and musicians. My favorite albums included one by the 50 Guitars of Tommy Garrett, and the soundtrack of "Doctor Zhivago." Inside the Sky River Rock Festival, I heard loud music from the stage at the foot of an open grassy hill, but didn't know whether it was Big Mama Thornton, James Cotton, Dino Valenti, Byron Pope, Peanut Butter Conspiracy, Alice Stuart Thomas, New Lost City Ramblers, Juggernaut, or Easy Chair; nor did I know if it was Country Joe and the Fish, It's a Beautiful Day, Santana, the Youngbloods, or the Grateful Dead. They were all there. Even Richard Pryor was there, and I don't think I knew of him at the time.

The ground, once covered with organic raspberries, was now covered with organic people, and in the midst of them was a couch that had been hauled out for Betty Nelson to sit on, flanked by those who helped put on the event, and Betty was obviously stoned and very happy. My brother, Paul, came with me at one point, and I remember the two of us sitting on the ground in the middle of everybody, facing the stage, but watching the people. Not far in front of us sat some topless women, which I was certainly thankful for. I remember telling Paul, "I don't know about hippie men, but I sure like hippie women." At another time, I enjoyed watching people running and sliding in the mud, and near them, a mime troupe performed.

Sultan was never quite the same after the Sky River Rock Festival and Lighter Than Air Fair, and neither was I. The business owners of Sultan sold out their goods, they did so well; and at least one state patrolman raved at how well-behaved and friendly the people were. I had experienced something profoundly new, an openness, expression, acceptance, freedom. Then, days later, I flew in military dress-greens uniform to Sandia Base, New Mexico, to begin training in Nuclear Weapons Maintenance before being sent to South Korea and having to miss Woodstock. But throughout the remainder of my army time I continued the Sky River Rock Festival, and was even nicknamed "Hippie." Eventually I managed to get out of nuclear weapons and into the mail room, where I subscribed to Seattle's underground newspaper, The Helix, one of the major sponsors of the event that turned on my hometown. And eventually I got out, honorable discharge, and that time no M.P. car pulled up in front of me.