This People's History is based on the early records of Wellspring Family Services, a private, non-profit organization helping families and children in Seattle and King County overcome life’s challenges. Founded in 1892 as the Bureau of Associated Charities, Wellspring Family Services has operated under a succession of names. At the time of the events described in this essay, it was called the Seattle Social Welfare League. This essay discusses the agency's difficulties keeping afloat during the perilous economic climate -- and changing social climate -- of the 1930s. The organization's services have changed over the years, but have always centered on a commitment to a stronger, healthier community. These archival records offer glimpses into aspects of Seattle history not well documented elsewhere, examining societal attitudes toward poverty, need, illness, and addiction -- all of which have altered considerably since Wellspring's early days. This is one of a series entitled "Out of the Archives," and appeared in March 2012 in Wellspring's monthly internal newsletter, The Fiddlehead. It was written by Wellspring Family Services executive assistant Deborah Townsend.

Relief vs. Social Service

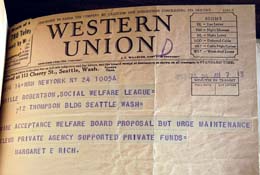

Bound into the book of Board records from 1918-1934 we find a telegram from the Family Welfare Association of America (by 2012 The Alliance for Children & Families). It’s dated July 24, 1933. It’s terse, as pay-by-the-word communications tended to be:

ADVISE ACCEPTANCE WELFARE BOARD PROPOSAL BUT URGE MAINTENANCE NUCLEUS PRIVATE AGENCY SUPPORTED PRIVATE FUNDS

What’s the story here?

Like most social-service agencies nationwide, our organization was overwhelmed by the numbers and needs of desperate unemployed people during the Great Depression. By 1933 the Social Welfare League (SWL), as we were then called, was in financial crisis and our continuing existence was in doubt, despite consolidation of office space, reduced hours of service, cuts in staffing, and transfer of some clients from our caseloads to King County. (Transfers which those clients vehemently protested, by the way: The Unemployed Citizens Council, a local self-help and advocacy group, organized numerous demonstrations outside our offices because they disliked the County systems and preferred to receive assistance from us. A compliment of sorts, but no doubt a huge disruption for already-overworked staff.)

Early in 1933, Washington State passed unemployment relief laws and King County set up a Welfare Board (KCWB) to administer public assistance systematically. At the same time Roosevelt’s New Deal agencies were gearing up at the federal level. Public assistance money finally began to flow -- but the new public safety net came with strings attached.

In June of 1933, a ruling came out of Washington, D.C. that as of August 1, all federal relief funds were to be distributed through public agencies, not through private organizations. The ruling further suggested that employees of any private organization that received federal relief funds could simply become employees of a public relief-granting entity. In Seattle, that meant the new King County Welfare Board, which promptly proposed to set up shop in all the SWL offices and absorb 13 of the SWL staff positions.

Board and staff members of the Social Welfare League were understandably alarmed. We had already worked with King County about division of case loads, but we definitely did not want to be absorbed into their bureaucracy this way.

The Board quickly set up a committee to review options (there weren’t many) and try to chart a course. This group concluded that “if the proposal [from the KCWB] were accepted it would mean not merely the first step in the direction of government support and control of family social work in Seattle but that it would mean the ultimate wiping out of the program of constructive service to families which had been built up here through long years of effort.” One Board leader stated it more bluntly: “if [we] were to enter into the arrangement proposed by the KCWB it almost certainly would result in the death of the League.” On the other hand, rejecting the proposed arrangement meant rejecting the federal funding and reducing our budget from about $450,000 down to the Community Fund’s base allocation of $90,000. The Executive Secretary of the Social Welfare League, Orville Robertson, wired off to the national organization of family service agencies to explain the situation -- it can’t have been unique to Seattle -- and ask for advice.

Hence the telegram recommending that the SWL accept the proposal to work with the King County Welfare Board but to make the effort to retain the “nucleus” of our work and remain an independent private agency, supported by private funding. On August 4, 1933, the Board debated the question and, on a split vote, accepted necessity and entered into a detailed agreement with the King County Welfare Board. The arrangement sent cases of straightforward unemployment relief to the County (yes, County staff worked out of our office space and we had to use their intake forms) but also recognized the Social Welfare League’s autonomy and expertise in family issues needing in-depth case management.

In the following year, 1934, our agency changed its name from The Social Welfare League to The Family Society of Seattle. This name change had two goals: to drop the word “welfare,” which already by then had a strongly governmental sound, and to emphasize what we did best: constructive social service for families. We handled relief vouchers on behalf of the brand-new Washington State Department of Public Welfare for one more year, but that task ended by mutual agreement in September 1935. At that point we were definitely out of the business of temporary financial assistance for the unemployed, definitely in the business of family social work -- our “nucleus” and core strength.