This People's History is based on the early records of Wellspring Family Services, a private, non-profit organization helping families and children in Seattle and King County overcome life’s challenges. Founded in 1892 as the Bureau of Associated Charities, Wellspring Family Services has operated under a succession of names. At the time of the events described in this essay, it was called the Charity Organization of Seattle. This essay examines the agency's policies in the early twentieth century, as compared with those in the early twenty-first century. The organization's services have changed over the years, but have always centered on a commitment to a stronger, healthier community. Wellspring’s archives illuminate the development of social work as a profession, the growth of the non-profit sector, and the relationship between private non-profits and governmental agencies. This is one of a series entitled "Out of the Archives," and appeared in May 2011 in Wellspring's monthly internal newsletter, The Fiddlehead. It was written by Wellspring Family Services executive assistant Deborah Townsend.

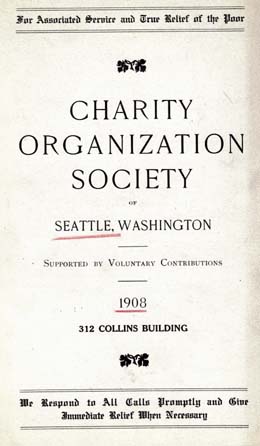

1908 Annual Report

In 1908 our agency was called the Charity Organization Society of Seattle (COS). Our annual report for that year is a simple little pamphlet of 18 pages, headed with a kind of mission statement (“for associated services and true relief of the poor”) and stressing on the title page that “we respond to all calls promptly and give immediate aid when necessary.” Our offices then were in the Collins Building at 520 2nd Avenue in Pioneer Square.

This document includes several elements which we still see in annual reports today, such as a financial summary, names of the Board of Directors, and the donor list for the year.

Agency finances: Income $7,182.98, expenditures $6,937.33, balance on hand as of September 30, 1908: $245.65.

Board structure: As we’d expect from any annual report, this one lists the members of the Board of Directors (21 of them). It also lists all the Board committees. Executive Committee and Finance Committee are predictable and we still have those committees today.

In 1908, our agency also had an Advisory Committee and an Employment Committee (duties unclear, probably relating to job placement for clients); a Legislative Committee doing what we’d now call advocacy work; a Nurse Committee to supervise a visiting nurse who provided home health care for clients; and groups of district visitors and “friendly visitors.” It might be a surprise to see a Tuberculosis Committee as the largest group of Board and community members. Tuberculosis was a major killer at the time, especially among poor urban populations, and public-health education was the only hope to stop its spread -- antibiotics and vaccines were still in the future. The COS was a leader in anti-tuberculosis efforts in our region, and in the following year, 1909, three the COS Tuberculosis Committee members joined with other physicians and community leaders to found the King County Anti-Tuberculosis League as an independent organization.

Donor list: The annual report gives a full list of subscribers (donors) with the amounts given. The largest single contribution recorded is $250.00 from Henry H. Dearborn (1844-1909); the smallest are a few entries at $1.00 each. We see many significant names from Seattle history on this list: Blethen, Burke, Collins, Colman, Denny, Frye. Two departed but well-remembered department stores are here (the Bon Marché and Frederick & Nelson), as are various banks and businesses. Numerous religious and civic organizations supported the work of the COS. The Spanish War Veterans group collected and donated $35. It all added up.

Secretary’s Report: The bulk of the 1908 Annual Report -- nine of the 18 pages -- is the “Secretary’s Report” by Virginia McMechen (executive secretary March 1908-November 1917), which gives some intriguing glimpses into social service organizations of that time. As many annual reports do, McMechen’s essay tells some client success stories. Curiously, she also chooses to give details about what she describes as “one of those discouraging instances in which constructive work appears to be almost an impossibility.” She also gives almost a page to the story of a family that, on investigation, doesn’t really need assistance and would actually be “lifted across the boundary line that separates the self-supporting citizen from the dependent on public charity” if the COS had given the relief that was requested. (“We must be careful not to pauperize,” she cautions. “The society must be careful not to help this man along his downward course.”) The report’s title page promised that the agency will give “true relief” and immediate assistance to clients who need it. On the other hand, all McMechen’s examples seem chosen to illustrate the difference between palliative and constructive charity -- she’s very firm about that distinction -- and to help the community understand what help is appropriate and what isn’t.

In a curious sidetrack that seems to criticize other charitable efforts, McMechen spends two whole pages on her opinions about “charity transportation” -- with particular focus on groups that authorize free or reduced train tickets without first checking whether the traveler actually has family or employment waiting at the other end of the trip. (“Last winter a woman and four children were sent to this city by a relief agency. We will not dignify it with the title of a charity organization.”) She is even a bit sarcastic about the individuals who arrive in Seattle asking for help from the COS. (“We find that most of our applicants are well-traveled people…”). This section of the report has a critical tone that we’d never use in our agency publications today.

Throughout the Secretary’s Report we see a shift toward rigorous investigative casework based on what McMechen calls “the principles of the new philanthropy, as opposed to older and less intelligent methods” (another little dig at other charity groups in the area?). Her final paragraph makes a bold pitch for these principles and the new directions the Charity Organization Society is taking in the first decade of the 20th century: “The word sympathy, like ... charity, is a much abused term. We cannot help our brother by sitting down and weeping with him. Clear vision does not accompany tears, though it may follow when the tears have spent their force. Modern charity is not heartless, as we are so often told. Instead it is most truly altruistic, teaching as it does ... that the best conditions can be attained only when the individual is considered, not as an individual alone, but in his relation to the whole social organism.”

What McMechen calls the “new philanthropy” is clearly based in what would become the new profession called “social work.”