The Bartell Candy Kitchen, located at 1906 Boren Avenue in Seattle, served many a sweet tooth for about 25 years during the early twentieth century. By the late 1920s, it churned out an average of a ton of candy per day and employed between 20 and 40 people, depending on the season. Candies came in a wide variety of flavors and consistencies, but Bartell's Golden Peanut Brittle is remembered as being one of the favorites.

Good Candy, Good Business

The origins of the Bartell Candy Kitchen are a little hazy, other than we know that George Bartell opened it as the company was beginning to rapidly grow in the early 1910s. The factory probably opened in 1913, perhaps a year earlier. Certainly it was up and running by the Christmas season in 1913, when an ad in the Seattle Times assured readers that "you always feel sure of the real goodness of Bartell candies … [made] fresh every day from the Bartell Candy Factory" ("Buy Lowneys…"). The exact reasons are also hazy why Bartell, a pharmacist, opened a candy factory. In a 1929 interview he explained that he had found that the company could make a much better grade of candy than it could buy, but conceded that operating the factory itself brought little in the way of direct profits.

Most likely Bartell, an astute entrepreneur, recognized that selling fresh candy in his stores was a good way to bring in business. He'd used candy to entice customers before. When he opened his Red Cross Annex store on 2nd Avenue on October 1, 1904, he provided 4,000 boxes of candy, one to be given to every customer who made a purchase, no matter how small, in the new store that day. Bartell saw that even if he didn't make money from the sale of the candy itself, the company would profit when customers purchased other items they might not otherwise have bought had they not come in for a bite of something sweet. The fact that the candy was fresh and locally made (and by a drugstore!) was just an added bonus.

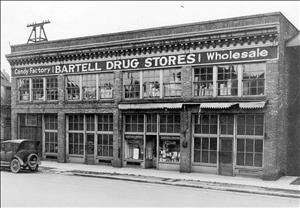

In 1914, Bartell moved the company's headquarters to the Boren Avenue location. The building now not only housed Bartell's headquarters and candy factory but also its warehouse. Bartell soon found it necessary to expand the structure, and in 1916 enlarged the building and added a second floor. The Seattle Times article that references this work adds that Bartell's ice cream plant was located in this building. However, the ice cream plant was part of Bartell Drugs' food operations, which were separate from the candy factory. (Bartell's food operations were big. They provided hot food to nearly all of its 23 drugstores and three tea rooms by the early 1950s, and also provided food for a cafeteria in one of Bartell's drugstores.)

The Bartell Candy Kitchen

The candy factory was a hit. Before long, the company was calling it the Bartell Candy Kitchen. It made a wide variety of candies; here's just a handful of the selections offered in a 1922 Bartell mail-order catalog (all prices are by the pound, unless otherwise noted):

After Dinner Chocolate Mints, 6 oz. -- 25 cents

Assorted Chocolates -- $1.00

Dark Chocolate Molasses Mint Chews -- 40 cents

Dark Chocolate Raisin Clusters -- 60 cents

Dipped Cherries -- $1.25

Fruit and Nuts -- $1.25

Fudge -- 30 cents

Golden Peanut Brittle -- 25 cents

Horehound lumps -- 30 cents

Lemon drops -- 30 cents

Lime Fruit Tablets -- 30 cents

Milk Chocolate Fig Chews -- 60 cents

Milk Chocolate Honey Nougat -- 60 cents

Milk Chocolate Marshmallows -- 60 cents

Walnut Patties -- 50 cents

The Bartell family recalls that the Golden Peanut Brittle was one of the best sellers. Also popular were End O' The Week Chocolates, described in a 1923 Bartell ad in The Seattle Times as "our best dark and milk-coated chocolates, made fresh each week for Friday and Saturday selling" ("Bartell Drug Stores…"). End O' The Week Chocolates came in a one-pound black and orange box and had something for every taste. Cream candies were offered in cherry, coconut, maple, orange, pineapple, and strawberry; chewy candies came in caramel, coconut, nougat, and peanut.

Other offerings over the years included the Garden Court Frappe, described in a 1924 Seattle Times ad as "Not a nougat, not a fudge, but a most delightful, fluffy, creamy foam composed of sugar, whites of eggs, and marshmallow. Maple flavor and loaded with pecans." The same ad also featured Honey Comb Chocolate Chips: "Fresh and crisp with that New Orleans molasses flavor, dipped in dark, sweet chocolate" ("Candy Specials").

Bartell Drugs did not only offer candy made by its factory. Its stores also stocked a wide variety of candies made by other manufacturers, such as the Imperial Candy Company in Seattle. Bartell drugstores also stocked Hershey bars, Nestles, chewing gum, lifesavers, and other treats.

A Ton a Day

In May 1928, the company opened a new building next door to its 1906 Boren Avenue location and moved its offices and warehouse to this new building at 1916 Boren. The candy factory remained in the older building. By this time it was churning out a ton of candy on a typical day, and more than that during the holiday season.

Less than a year later, the factory attracted the attention of The Seattle Times. In February 1929, the paper wrote about the factory in a feature in its National Weekly, a Sunday section rather similar to today's (2012) Pacific Northwest magazine in the Sunday Seattle Times. The article gives a vivid snapshot of the Bartell Candy Kitchen as its operations peaked in the last year of the Roaring Twenties:

"Surprisingly light and airy and clean is this factory. The outside walls are virtually all glass. The floors are concrete, scoured until they shine. Tables are metal topped ... . Men in immaculate white ducks [shoes] preside over shining hammered brass kettles. Girls [young women] in trim uniforms dip chocolates and box and pack them" ("A Seattle Druggist…"). In 1929 the factory employed more than 20 people during normal operations, but doubled its workforce during the weeks before Valentine's Day and between Thanksgiving and New Year's.

The factory's supplies were ordered in bulk -- really big bulk. Ten gallons of whipping cream were used daily, with Brazil nuts ordered by the ton, walnuts in even larger quantities, peanuts by a half railcar load, and sugar by an entire railcar. Milk, butter, and eggs were also used in large quantities. Being able to order such colossal amounts of ingredients also enabled Bartell Drugs to make more of its own candy than it had in 1922. The Seattle Times reported in its 1929 article that 95 percent of the candy Bartell Drugs sold in its 14 stores was made in its candy factory.

The Art of Candy Making

The article devoted considerable space to the manufacturing process, explaining that some candies were better when delivered fresh, while others improved if they sat for a few days. The paper added that fresh candy was often delivered to Bartell's stores while it was still warm, something the company prided itself in doing. The ingredients to make the candies were weighed "correct down to the fraction of an ounce" ("A Seattle Druggist…"), and then put in a large copper kettle. The paper made special mention that the ingredients were heated with electrical heat -- most of Seattle had access to electricity in 1929, but this wasn't true in rural areas in the state or even in Seattle's Eastside -- and stirred with a special electrically driven paddle.

Soft candies were cooked at about 240 degrees; hard candies at 350 degrees. To monitor the kettle's contents, thermometers were placed directly in the boiling liquid and closely watched. Yet despite all the precise preparation, it was still a subjective call based on the candy maker's eyes and nose when he felt the batch was ready. Once it was, the syrupy mixture was put into a beating machine to cool and then was whipped into the proper consistency. This usually took half an hour or so.

If a fruit candy was being made, it was flavored with natural fruit flavors and crushed fruit -- "no artificial flavor is used," emphasized the article. The next step was to send the candy to the chocolate dipping room, where it was rolled by hand and machine-cut to the desired size. The chocolate dipping room itself was a sight to behold. Explained the paper:

A Revelation to the Uninitiated

"Expert chocolate dipping is a revelation to the uninitiated. Girls do the work at almost incredible speed. The molten [chocolate] coating is before them on a marble slab; the fillings on trays at the left. A left hand darts out and palms a filling while the right is coating another. Coated to the proper thickness, the chocolate receives the parting tap that gives it its characteristic uneven top, and another filling flies from the left to the right hand ... . Girls coat as much as 200 pounds of chocolate in a single day. No machine that can compete with them has been devised" ("A Seattle Druggist…").

George Bartell Jr., in an undated memoir written around the year 2000, added an additional explanation that the article missed. Since the kitchen made its chocolate-covered candies in various flavors, the candy maker had to be able to correctly tell the flavor of the finished product after it was coated with chocolate. Bartell said that the candy makers put an individual swirl on top of the candy as a finishing touch to identify the flavor at its center.

A 1932 article in the Seattle P-I also took a look at the candy factory, but didn't go into the depths that The Seattle Times article had more than three years earlier. It did talk about the duties of Frank Shull, manager of the candy department. The article claimed that he inspected the candy departments in each of Bartell's stores (the company had 17 by this time) at least once a day and at some stores twice a day. Explained the P-I, "Shull has made a study of pleasing the palate by dainty confections ... [and] follows closely public tastes in candies" ("Candy Sold…").

Bartell Drugs continued to use its candies as a marketing tool when it had a holiday sale, special sale, or opened new stores. When Bartell's opened its 16th store at Pine and Westlake in 1930 (not to be confused with its better-known "triangle store," which opened five years later across the street), it had 15 tons of candy ready to give away in boxes that usually cost 75 cents. This giveaway didn't happen just at its new store, but at all Bartell locations throughout Seattle during a three-day sale. There were restrictions. Customers had to purchase $1 or more, and cigarettes, soaps, and cleaners didn't count toward the purchase price. Even if you didn't want to buy anything, you were still invited to the grand opening: "Not necessarily to make a purchase, but to see the achievement that your friendship and patronage has made possible" ("Bartell's Greatest…").

The Candy Kitchen Closes

By the time of the 1932 P-I article, employment had ebbed in the candy kitchen to about 15 men and women, perhaps as a result of the Great Depression (though the Bartell Drug Company as a whole did well during the Depression). The kitchen's close followed late in the 1930s, and is as hazy as its beginning. An ad can be found in the November 18, 1937, Seattle Times for Bartell peanut brittle, but that's the last mention in that paper of the famous Bartell brittle or, for that matter, any candy actually made by Bartell's.

George Bartell Jr. later wrote in notes prepared for the company's 1990 centennial that the candy factory closed "about 1936 or so" (it probably closed about two years later), but provided no explanation of the reasons behind the close. One may speculate that changing times and the factory's thin profit margins were contributing factors. But the Bartell Candy Kitchen left behind a quarter-century of satisfied customers and a unique aside in the history of the company and of Seattle.