On December 13, 1983, Pacific Northwest Ballet premieres a new production of Nutcracker. The ballet is choreographed by Pacific Northwest Ballet artistic director Kent Stowell (b. 1939) with sets and costumes designed by famed children's book author and illustrator Maurice Sendak (1928-2012). The production is an immediate success with local audiences and achieves national acclaim, quickly becoming a classic Seattle holiday tradition.

Lew Christensen's Nutcracker

Founded in 1972 (as Pacific Northwest Dance -- the company began referring to itself as Pacific Northwest Ballet in 1978 and was formally renamed in 1979), since 1977 Pacific Northwest Ballet had been led by artistic directors Kent Stowell and Francia Russell (b. 1938). The pair worked steadily to raise professional standards at the company and at Pacific Northwest Ballet's school.

From 1975 to 1982, the company presented a production of Nutcracker choreographed by San Francisco Ballet artistic director Lew Christensen (1909-1984). The first Christensen Nutcracker featured guest soloists Cynthia Gregory (b. 1946) and Ivan Nagy (b. 1943) along with advanced students from the company school, and sold out eight performances in the Opera House.

The production remained very popular, as is often the case with the holiday staple. For virtually all American ballet companies, Nutcracker (in any production) is not only a community holiday favorite, but a powerful engine of financial success. Emotionally satisfying, transporting, presenting a clear but fantastic story line, on offer at Christmas when audiences are in the market for emotional succor, Nutcracker is by far the most popular ballet presented in America. For many audience members, an annual Nutcracker viewing is sufficient, and defines "ballet." For some viewers, Nutcracker is an entry-point into ballet as an art form. For the companies that present it, Nutcracker both draws potential new audience members and pays the bills.

Nutcracker History

While plot points vary from production to production, most Nutcrackers portray a young girl's dream visit to a kingdom of sweets and other delights. The Nutcracker who gives the ballet its title is a gift to the girl -- called Marie in Hoffmann's story and Clara in most productions, including Pacific Northwest Ballet's. The Nutcracker is her prince and magical transporter to the enchanted kingdom. The music is by Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) and the story was inspired by "The Nutcracker and the Mouse King," written in 1817 by E. T. A. Hoffmann (1776-1882).

The ballet was adapted from the Hoffmann story by the member of the Dumas family known as Alexandre Dumas pere (1802-1870), and first staged in 1892 at the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg in a production choreographed by Lev Ivanov and the esteemed French choreographer Marius Petipa (1818-1910). The first production outside Russia was at the Sadler's Wells Ballet in London in 1934, choreographed by Nikolai Sergeyev (1894-1989). The first full-length American production of Nutcracker was staged by Willam Christensen (1902-2009) for the San Francisco Ballet in 1944. New York City Ballet, where both Kent Stowell and Francia Russell danced, first performed George Balanchine's (1904-1983) Nutcracker in 1954.

Stowell/Sendak Nutcracker

Most ballet companies' Nutcrackers are very loosely based on a greatly simplified version of the Hoffman story. One of the noteworthy aspects of Pacific Northwest Ballet's Nutcracker was that Stowell and Sendak went back to the original source, re-introducing the story of Princess Pirlipate into the ballet, and eliminating both the land of sweets and the Sugar Plum Fairy.

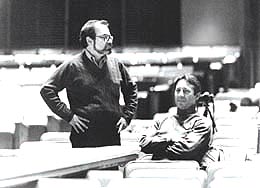

Kent Stowell began contemplating creating a new production of Nutcracker as early as 1980. Francia Russell suggested children's book author and illustrator Maurice Sendak, whose genre-breaking picture books were bestsellers. Sendak, who illustrated scores of books and eventually wrote more than a dozen, was awarded the 1964 Caldecott for Where The Wild Things Are. In The Night Kitchen was a 1971 Caldecott Honor Book. As parents of three children born between 1966 and 1974, Stowell and Russell were familiar with Sendak's books.

Stowell approached Sendak about the project in early 1981, proposing that they examine the familiar tale and do something new. Sendak later remembered, "There was nothing in Nutcracker, other than the score, that interested me at first. Everything that made Nutcracker a traditional holiday delight (humungous Christmas tree and fatuous Candyland) depressed me. And what, for goodness sake, would Nutcracker be without them? A good deal, Kent and I discovered" ("Bringing a Vision...").

Sendak described Nutcracker as a concept several years after its premiere to the New York Times: "Nutcracker is the exception to every ballet rule; it is not a proper ballet (ask any dancer) but rather a delightful mishmash of fairy tale, mime and dance all threaded through with perhaps the best ballet score ever composed. Interpreters take liberties with it -- historically, they always did" (November 23, 1986).

Taking a Risk

The project marked the first time Kent Stowell had created a full-length ballet specifically for the company, and thus was a proving ground. Even as Stowell set choreography and Pacific Northwest Ballet's wardrobe and scene shops began building costumes and sets, some donors expressed doubt. One board member, dubious about replacing a best-selling production with a complete unknown, favored phasing in Stowell's version slowly -- perhaps presenting the first act of the new version with the second act of the old favorite. Another board member suggested that Russell could have dancers ready to present the old version in case Stowell and Sendak's did not gel. These ideas -- desperate and unworkable -- were ultimately tabled.

Publicity efforts were many. The company sponsored Nutcracker tea parties with excerpts by costumed dancers. For $250, opening night patrons could purchase tickets to a Nutcracker gala that included dinner at Trader Vic's, tickets to the premiere, and a backstage party after the performance. Seattle Times dance critic Carole Beers, after exhorting readers to make haste to the box office before tickets were gone, cautioned that the Stowell/Sendak Nutcracker would be "different from any we've seen. Very different -- particularly when compared with PNB's sugary, episodic and illogical version done here the past seven [sic -- actually eight] years" (December 9, 1983).

Beers's review a few days later enumerated the differences: "This version goes back to E. T. A. Hoffmann's original tale, "The Nutcracker and the Mouse King," about a Mouse King turning a girl into a hag, with the Nutcracker/Prince coming to the rescue. That, of course, concerns a young girl's hesitation on the brink of womanhood, about her simultaneous fear and attraction to it, and the fantasies that fear and attraction inspire" (December 14, 1983).

In its first year alone, the Stowell/Sendak Nutcracker played to 99 percent capacity, more than doubling revenue compared with the last year the Christensen version was presented. The company presented 26 performances, attended in total by 78,000. The Nutcracker premiere also marked the beginning of Pacific Northwest Ballet's long association with Stewart Kershaw (b. ca. 1941), who served the company as conductor and musical director until October 2009.

Completely Classic

In 1984, Maurice Sendak illustrated a picture book version of E. T. A. Hoffmann's Nutcracker. An immediate success, the book as of 2012 was still in print, and for sale in Pacific Northwest Ballet's gift shop.

In 1986, Criterion Films released a film version of PNB dancing the Stowell/Sendak Nutcracker. Preparing for and filming the movie occupied the company for nearly six months. In December 1986, local audiences enjoyed watching the movie cast perform live. Seattle Times critic Wayne Lee conceded, "As usual, though, the stage version is much better than its big-screen adaptation. The colors are more vivid, the sounds are more stirring, the action is more immediate and, of course, it is live" (December 10, 1986).

Pacific Northwest Ballet toured the Stowell/Sendak production of Nutcracker to Vancouver, B.C.; Portland, Oregon; and Minneapolis. As of 2012, Nutcracker accounted for approximately half of Pacific Northwest Ballet's earned-revenue budget. The ballet became a yearly staple, performed every season for more than three decades following its 1983 premiere.

Early in 2014, PNB announced that that year's holiday production of the Stowell/Sendak Nutcracker would be the last. The company would continue performing Nutcracker every year, but beginning in 2015 planned to do so using George Balanchine's 1954 choreography. The Sendak sets and costumes were to be stored (leaving open the possibility of a revival at some future time), and replaced with new ones designed by another children's-book author, Ian Falconer, known for his Olivia book series.