Robert E. Strahorn (1852-1944) and his wife Carrie Adell Green "Dell" Strahorn (1854-1925) had a significant impact on the Northwest in the 1880s and 1890s, through their writings that publicized the many attractions of the area, and his work with the Union Pacific Railroad, the Oregon Short Line Railroad, and the Idaho and Oregon Land Improvement Company. In 1898, the Strahorns moved to Spokane, and Robert Strahorn spent the next 15 years helping build a network of rail lines and facilities including Spokane's Union Station, as well as water-power and irrigation projects, throughout Eastern Washington. In spite of his impact, not much is known about Robert Strahorn, and not much has been written about him. This account of his life and work by John W. Lundin and Stephen J. Lundin comes from a book the Lundins are writing about their great grandparents, Matthew and Isabelle McFall, who were early pioneers in Idaho's Wood River Valley, and is based on Robert Strahorn's unpublished autobiography Ninety Years of Boyhood, Dell Strahorn's 1911 memoir Fifteen Thousand Miles by Stage, and other primary and secondary sources.

Working for the Union Pacific

After the first transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869, the Union Pacific Railroad began planning a direct connection to the Pacific Northwest. Surveys were made, and a route was located along the Snake River in Idaho and the Columbia River in Oregon. Strahorn was hired as a publicist for the Union Pacific Railroad in 1877 by Jay Gould (1836-1892), who controlled the railroad. Robert and Dell Strahorn traveled throughout the West, mainly by stagecoach, and wrote books and newspaper articles extolling the attractions and virtues of life "out west," designed to attract easterners to move to the remote Idaho Territory. Strahorn also made recommendations to the Union Pacific about specific routes its tracks should take, and where stations and towns should be located. Strahorn took credit for helping convince the Union Pacific to build its Northwest link, the Oregon Short Line, and to build the Wood River Branch from Shoshone to Hailey, in 1883. U.P.'s plans were finally brought to fruition when the Oregon Short Line was built from Granger, Wyoming, to Portland, Oregon, between 1882 and 1884.

In 1882, the same year that the Union Pacific began building the Oregon Short Line tracks from Wyoming into Idaho, Strahorn and others formed the Idaho and Oregon Land Development Company, which was affiliated with the Union Pacific, to buy townsites in advance of the arrival of the tracks. Since Strahorn knew the route of the railroad before the tracks were built, the company could buy the empty desert land cheaply and make large profits from developing new towns around railroad stations to be built in the future. Strahorn spent much of the 1880s developing those towns. His company developed many towns along the Oregon Short Line tracks running through Central Idaho, including Hailey, Shoshone, Mountain Home, Caldwell, and Weiser, as well as Huntington, Oregon. Strahorn and his partners later built the Alturas Hotel in Hailey, and the Hailey Hot Springs Resort in Croy Canyon. Unfortunately, both facilities burned down.

Strahorn's publication about Idaho, The Resources and Attractions of Idaho Territory, for the Homeseeker, Capitalist and Tourist, published in 1881, was paid for by the Idaho Territorial Legislature, but secretly backed by the Union Pacific Railroad. In 1911, Carrie Adell Strahorn published her memoir, Fifteen Thousand Miles by Stage, in which she described the couple's travels in Idaho and throughout the West in the 1870s and 1880s, much of it based on newspaper articles she wrote contemporaneously with their travel. The book contains wonderful descriptions of travel conditions and life in those early days of Idaho's history.

Developing Fairhaven

Strahorn left Idaho in 1888, but continued his work as a promoter, speculator, and developer. He got involved in a project to develop Fairhaven, a small town on a "glorious harbor" just south of Bellingham in Whatcom County, which hoped to be the western terminus for the Great Northern Railway being built by James J. Hill (1838-1919) from Minnesota to Washington. Strahorn played his usual role of promoter and publicity hound for the project to attract investors for the Fairhaven Land Company, which had acquired large landholdings for a townsite and a vast terminal to donate to Hill to induce him to use Fairhaven as Great Northern's western terminus.

Strahorn called Fairhaven "the New York of the Pacific" because of "Mr. Hills great docks, his proposed fleet of connecting palatial ocean liners, railway shops, and other activities, plus our unrivaled natural harbor location opposite the ocean entrance to the Sound, shortest route to the world's new treasure house, Alaska, the Orient, and balance of the universe." The project fell apart when James J. Hill selected Seattle as the terminus.

We had just about fairly commenced the wide-spread custom of enticing the other rapid-fire money makers to risk their shoestring capital on city lot contracts when advised that Mr. Hill had changed his mind and would utterly ignore supplying Fairhaven with any one of those promised luscious plums for sustaining the boom.

Strahorn later wrote candidly about the Fairhaven project, in his unpublished autobiography, Ninety Years of Boyhood:

Thus, with immense natural resources in the tonic air of Puget Sound, was the stage all set for the most dazzling real estate promotion orgies of the century, attracting armies of past masters in real estate manipulation inside and outside the RR organizations ... . My extensive experience in the publicity line marked me as the leading hot-air instrument. The extremes to which we innocently went in our lurid word pictures of the future metropolis and the general urge of everybody to get in on such an alluring opportunity led to fabulous gains in real estate values hourly. It was my business to seek out and broadcast every known resource and even some not too tangible, to promote settlement and quick building of the Puget Sound Empire ... . Our blueprints desecrated the charmingly seductive solitude by showing docks, elevators, lumber mills, railway approaches to busy wharves, and smokestacks bravely peering from the old silent forests.

Boston to Spokane

Strahorn was left financially devastated by this lost opportunity, a condition made worse by the Silver Depression that began in 1888, the great Baring Bank failure in London in 1890, and the total collapse of the silver market in 1893, which led to a serious worldwide depression.

As a result of the depression, the general failure to pay taxes, and the lack of currency in circulation, governments of all levels in the West sold interest-bearing warrants to cover their expenses and outlays. The warrants bore interest rates of six to 10 percent and were debts of tax-paying entities. As a result, the Northwest was flooded with hundreds of millions of dollars of warrants that were used as currency to pay public debts and obligations. Banks had so many of these warrants that they were sold at discounts of 10 to 50 percent of their face value. Strahorn decided that trying to establish a market for these warrants would be his next challenge. He invested in warrants and moved to Boston where he believed there would still be money available, to establish a business of brokering "this flood of unsalable public obligations before their depreciation became absolutely ruinous ..."

Strahorn spent much of the 1890s in Boston working as an investment banker, promoting a market for these public warrants, with some considerable success. In 1898, he decided to "close out his successful bond business" and move back West to get back into railroad financing and construction. After spending a winter in Hawaii, and another in Mexico and Cuba, the Strahorns settled in Spokane, where he continued his promotional activities in a variety of ventures.

Railroad Connections

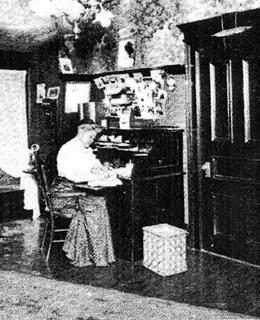

The Strahorns were wealthy when they settled in Spokane, and they "moved into the very core of prominent society." They bought a mansion that they remodeled at a cost of $100,000. It had steam heat (the first house in Spokane to do so), and featured a bowling alley, nine bedrooms, and 10 fireplaces. Dell Strahorn entertained lavishly, giving elaborately planned receptions for up to 400 people. She wrote her book Fifteen Thousand Miles by Stage, published in 1911, in that house in Spokane. Strahorn said in his autobiographical manuscript that Dell was an important part of his business activities in Spokane, contributing greatly to his success:

As a leading example, in creating our Spokane home we far exceeded our own modest taste and mutual needs for comfort, wishing to encourage in large degree these public activities. So, if I had some big gathering of men on hand, their wives luxuriated in the elaborate provision for entertaining up there among the evergreen pines and other rare foliage and flowers of far spread lawns, some gathered from distant lands and carefully nurtured by the ever thoughtful hostess. From billiard room, bowling alley and buffet in the basement every modern luxury through the commodious four floors was wide open for such throngs of eager guests.

Strahorn went to Spokane to build the North Coast Railroad to bring Spokane and Walla Walla closer to Portland and Seattle, and to develop water systems for both power generation and irrigation. Prior to the turn of the century, the majority of immigration to the Pacific Northwest had gone to Oregon, but by 1900, most of the desirable Oregon locations had been taken and promoters were developing more railroads north of the Columbia.

Spokane excited Strahorn because of its railroad connections. Spokane was linked to national markets by the Northern Pacific and Great Northern, which had routed cross-country lines through Spokane to Seattle, and by the Union Pacific, which accessed the city through its Oregon Washington Railway & Navigation line from Pendleton, Oregon. In addition, many local businessmen were building short rail lines to access Spokane's rich surrounding areas. Strahorn said that Spokane in the early 1900s resembled Denver in earlier days with its "creative and railroad-building galaxy of irrespressibles" who were building new rail lines reaching out in every direction from this capital of the Inland Empire. Daniel Chase Corbin (1832-1918) annexed the Coeur d'Alene country to Spokane by a combined rail and water line, then built the Spokane Falls & Northern Railway north into the Colville country, extended the line to mines in Rossland, British Columbia mines, and finally connected it to the Canadian Pacific transcontinental railroad.

Frederick A. Blackwell (1852-1922) built an electric railway line to Hayden and Coeur d'Alene lakes in Idaho, and another southeast to the Palouse wheat-producing country around Colfax in Whitman County and Moscow, Idaho. He also built the Washington, Idaho & Montana Railway to the Potlach lumbering region and the Idaho & Washington Northern to Metaline Falls in Pend Oreille County and Spirit Lake, Idaho.Others built the Spokane & Seattle Railroad to the Big Bend wheat country. Strahorn was excited by this frenzy of activity, asking "[w]here in all our country is there another community that can match this marvelous display of public spirit and accomplishment by a group of men meagerly equipped with capital and altogether having had no previous railroad experience?"

Audacious Soaring Plan

Strahorn saw that three national railroads were building new lines to the Northwest, and he came up with one of his typical grandiose plans, as later described in his unpublished Ninety Years of Boyhood, to:

[supply] their main lines, feeders, terminals, and other needs in that country. After carefully surveying the situation, I spend several years in engineering and assembling rights of way, franchises, and terminals for the North Coast Railway Company, which I organized to utilize such facilities. My general plan was a new shortest line from Spokane to Portland of 368 miles, and there commencing with the transcontinental line connecting therewith on Columbia River near Wallula to be built west through Yakima Valley, the largest and most productive in the state, to Puget Sound, about 250 miles. Both lines were to have certain necessary feeders, one of these southward to that golden Walla Walla granary. Then, at the important potential railway center of Yakima, to construct and connect up an electric railway system tapping four highly productive valleys, and, as far as necessary, serve the city and suburbs. Also a line from Spokane southeast through that magnificent Palouse wheat country to Lewiston, Idaho, several hundred miles more, making altogether a perfectly independent system of approximately 1000 miles to compel recognition of the existing and proposed main liner.

Strahorn realized his "audacious soaring" plan would cost from $30 to $40 million, although he began with a "shoestring" of several hundred thousand dollars. Key to his plan was to interest a railroad owner to fund his work. Strahorn convinced Edward H. Harriman (1848-1909) to invest Union Pacific funds in the venture, since Strahorn was challenging the plans being made by James J. Hill for his Great Northern Railway in the Northwest. Hill was Harriman's long-time nemesis and the two railroads were bitter competitors. Harriman's participation had to be kept a secret to prevent Hill from learning his role. Strahorn said: "Necessary funds would be deposited to my personal account in such banks as I would designate, in a manner impossible to trace and to be utilized only by personal checks." Harriman's only advice to Strahorn was "whatever happens, Strahorn, don't get licked." Strahorn kept Harriman's participation secret, earning him the names "Sphinx" and "Man of Mystery."

The North Coast Railroad was incorporated in 1910, with $60,000,000 in capital. In addition to building rail lines, Strahorn's venture acquired property for freight and passenger terminals in Spokane, Tacoma, and Seattle, as well as the approaches into those cities that he would lease to the three railroads building lines into the Northwest, since his property "was superior to even the existing ones of the old established routes." Strahorn built Union Station in Spokane, at a cost of more than $500,000, for use by all three national railroads. He convinced the Chicago, Milwaukee & Puget Sound Railroad (generally known as the Milwaukee Road) to route its new line through Spokane to use the facilities he built, instead of going 45 miles south of the city as it originally planned.

Strahorn purchased the Yakima Valley Transportation System that ran electric lines in Yakima, and extended its lines through the nearby valleys, producing what he called "that splendid moneymaker." However, Strahorn's entire plan was not completed, and his line stopped at Yakima rather than going all the way to Seattle because of an agreement worked out by the rivals Harriman and Hill. Harriman gave up the Yakima-to-Seattle link in exchange for joint use of the Columbia River bridge near Portland and double-tracking of the rail line between Portland and Seattle to provide an entrance to Puget Sound via Portland for the Union and Southern Pacific railroads. The golden spike for Strahorn's railroad system was driven on September 14, 1914, an event he recalled in his autobiography as "the stupendously brilliant climax of 1914 at Spokane."

The grand finale to these railroad operations had to be the driving of the golden spike, followed by a great banquet at the superb Davenport Hotel on September 14, 1914, all under the auspices of its wide-awake Chamber of Commerce. At these functions there was a supreme get-together and bury-the-hatchet effort in the general felicitation over the task so splendidly finished. We drove the golden spike in a most unique and impressive setting. This was at the joining of the rails on top of the monumental railway bridge midway between its east and west ends. The engines of the Union Pacific train approaching from the west and of the Milwaukee train from the east, these exalted highly decorated ones a few apart overlooking Spokane's chief glory -- the falls and rapids of the beautiful river underneath ... . There I of course had to join others in driving the spike with the silver hammer, and make the address, and at the Davenport Hotel banquet following, the golden spike was presented to me with the unstinted acclaim of many.

Water and Power

Strahorn also invested in power generation and irrigation facilities. He said that in developing railroad towns in Idaho, he gained considerable experience building highways, bridges, and telegraph lines, and supplying irrigation works, electric power plants, and water works for domestic for the new communities. "I particularly enjoyed the handling of water of mountain streams, in creation of hydroelectric works, irrigation and gravity water system works." His first experience was establishing the electric lighting system for Hailey, Idaho, after 1882. Strahorn invested in several power and irrigation works during his career, from which he said he made a considerable return. He formed Yakima Light & Power and built power plants and a gas utility plant in Eastern Washington while he was developing the railroad system in Washington. These business ventures were later consolidated into the Puget Power & Light Company. Strahorn developed the first significant reclamation project in Pasco, diverting water from the Snake River. He also owned two power plants in Idaho which were the "apples of my eye" that he operated for 25 years, which he sold in 1927 for "hundreds of thousands in excess of the value of the property."

Strahorn's work resulted in a boom for Spokane and its tributary country. In all, $110,000,000 was spent in five years by railroad interests in the area. Strahorn was lauded for his work, which included convincing the Milwaukee Road to come through the city.

After Strahorn's railroad was completed, and Harriman's role in financing the venture became known, the North Coast Railroad was consolidated with other Harriman lines in the Northwest, as part of the Oregon-Washington Railroad & Navigation Company, and Strahorn became vice-president of the larger corporation. After Strahorn's railroad projects were finished in Washington, he turned his attention to "our further giant tasks already inaugurated along the Pacific." He went into railroad building in Oregon.

Building Railroads in Oregon

During the 1910s, Strahorn became involved in promoting railroads in Oregon, initially working with Harriman's interests and later on his own. He became President of the Portland, Eugene & Eastern Railroad owned by the Southern Pacific, and built an electric railway line through the Willamette Valley.

Strahorn then worked on providing rail service to central and eastern Oregon and northern California, areas not served by rail traffic. He felt personally responsible for this situation, because in the 1880s he had recommended that the Union Pacific not build its line to the Northwest through central Oregon to Portland, but rather go along the Columbia River. As late as 1914, the only rail service in the region consisted of a Great Northern branch from the Columbia River to Bend and a Southern Pacific branch to Klamath Falls. The major railroads girdironed central and eastern Oregon along its outer edges, but its interior was not served by rail.

Strahorn came up with an ambitious plan to fill this gap and gain access to rich agricultural areas and untapped timber supplies: a series of new rail lines using the Oregon, California & Eastern Railroad. He planned a 400-mile rail system based at Silver Lake, with branches running to Klamath Falls, the Nevada-California-Oregon Railroad at Lakeview, the Union Trunk/Union Pacific line at Bend. Strahorn also considered additional lines and connections extending as far as northern California and Nevada. However, World War I interfered with his plans and only one line was built. Running from Klamath Falls to Spragues River, it was completed in 1923 and opened up vast stands of timber to harvesting.

Strahorn spent several years trying to stop the expansion of the Great Northern Railway from Bend to Klamath Falls, then on to San Francisco, an expansion that would divert traffic from his own Oregon, California & Eastern line as well as Harriman's Southern Pacific. He expanded his tracks and those of the Southern Pacific around Klamath Falls to prevent the Great Northern from getting easy access to the city. He led opposition to the expansion in two separate Interstate Commerce Commission hearings, but lost, and the Great Northern gained approval to extend its Empire Builder service from Saint Paul all the way to San Francisco. Strahorn felt somewhat vindicated since the Great Northern never finished its plans, and the Empire Builder never made it to San Francisco.

During the middle of this fight, Dell Strahorn died in San Francisco on March 15, 1925. After her death, The New York Times described her role as "Mothering of the West. That's quite a title. But then, Carrie Adell Strahorn was quite a woman." Robert Strahorn included only three sentences in his autobiography about the death of the woman who shared so much of his life:

Here intervened the first real crushing, heartrending sorrow of my life, the sudden death of my deeply loved, superb wife, who had been my inseparable companion, my greatest inspiration and staunchest support for nearly fifty years. The earth, which at times seemed only dangerously slipping before, was now indeed gone from under. How attempt to picture the glory surrounding, permeating, and emitting from such angelic womankind?

Strahorn remarried in 1926, and he devoted 25 pages to describing his subsequent two-year round-the-world trip with his new wife. This disparity in treatment of the two Mrs. Strahorns is surprising, but must reflect his perception of life at age 90 when he wrote his autobiography.

Final Ventures

Strahorn had made another fortune from his business activities in the Northwest, but shortly before the panic of 1929 he decided to invest heavily in San Francisco real estate, borrowing heavily to do so. He pledged all of his stocks and bonds as collateral for the loans, and when the Great Depression of the 1930s destroyed the financial markets, Strahorn lost everything and signed over his property to his creditors to avoid foreclosure. He ventured back into the mining business in the late 1930s, working with associates to buy and develop mines in Oregon and Idaho (near the Salmon River) that were shut down or operating inefficiently because of the lack of capital. Strahorn worked on obtaining financing for their efforts. His second wife died in 1936, during the middle of his mining ventures.

Ninety Years of Boyhood, Strahorn's unpublished autobiography completed 1942, ends on a positive note reflecting his optimism that his new mining ventures would succeed. Robert E. Strahorn lived to be 92 years old, dying in San Francisco in 1944, a poor man. A Spokane newspaper said: "Robert E. Strahorn, 92, who died Friday night in San Francisco, was a colorful figure of the Old West, remembered here as a railroad and town builder and early-day newspaperman."