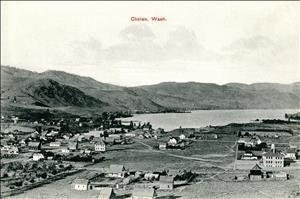

The City of Chelan, in the North Central Washington county of the same name, straddles the entrance to the Chelan River at the southern extremity of Lake Chelan, the largest natural lake in Washington. Chelan (the town) was started in the late 1880s, sustained during its first decades by logging, mining, agriculture, and early tourism. Although its remote location slowed population growth, a magnificent setting and abundant resources eventually drew many to the area. The town prospered and the Chelan River was soon dammed for irrigation and hydropower. In more recent years, with the timber and mining industries largely inactive, Chelan has been best known as a scenic resort community supported primarily by tourism, with contributions from orchards, vineyards, and wineries.

Long, Narrow, and Deep

Lake Chelan was formed more than 10,000 years ago, carved out by a valley glacier that extended from the crests of the Cascade Mountains to the Columbia River. The narrow lake (two miles at its widest) snakes through the hills for more than 50 miles in a northwest to southeast direction, ending in the south at the inlet to the Chelan River. It is the largest, longest, and at nearly 1,500 feet, deepest lake in Washington and the third deepest in America. Ironically, it empties into the state's shortest river -- the Chelan, which (although dammed dry for much of the twentieth century) flows barely four miles before joining the Columbia for the run to the sea.

The lake is fed by multiple streams and one sizable river, the Stehekin. Along much of its length the shoreline is dominated by steep terrain and is nearly inaccessible by land. But in the southeast it opens into an area of fertile, rolling hills, and it was mostly here that both Indian and non-Indian settlers chose to put down roots.

The Chelan Indians

It is believed that regular human habitation at Lake Chelan began about 10,000 years ago when a group that became known as the Chelan settled at various places along the margin of the lake. Thought to be an offshoot of the much larger Wenatchi Tribe, they spoke the Wenatchi dialect of the Interior Salishan language.

That the tribe came to be called the "Chelan" may have been the doing of Alexander Ross (1783-1856), an explorer for the Pacific Fur Company. Traveling along the Columbia River from 1811 to 1813, Ross came to the place where it is joined by the Chelan River. Local Indians told him that the name of the river was Tsill-ane, ("deep water") and that it arose from "a lake not far distant" (Early Western Travels, 149). In his diaries, and without further comment, Ross included the "Tsill-ane Indians" as members of the "Oakinacken nation" (Early Western Travels, 275). Whether before Ross the people who now are called the Chelan used the name "Tsill-ane" to refer to themselves appears unknowable.

At the time whites started making significant encroachment into the upper-Columbia region, Innomoseecha was the recognized chief of all the Chelans, and he would represent the tribe at important councils. But the Chelans lived in largely independent bands, although they would come together to meet common challenges. Mobility, intermarriage, and slavery had blurred tribal distinctions in the region before the arrival of outsiders, and the Chelans and Entiats were often considered one people by early settlers and by federal and local governments. This oversimplification was heightened when they and several other tribes and bands were consolidated on the Columbia Reservation in the late 1870s.

The Chelans maintained an all-season village called Yenmusi' Tsa ("rainbow robe," believed to be an allusion to the play of light on the lake's surface) where the town of Chelan now lies and summer habitations north and slightly inland from the lakeshore. They regularly crossed the Cascades Mountains on foot and traveled west down the Skagit River to trade with tribes in north Puget Sound; traveled northeast to Kettle Falls and southwest to Celilo Falls to trade and to fish; and trekked east to the plains of Montana to hunt buffalo. They were not notably warlike, but would fight when necessary and were fully capable of defending themselves against attack.

In their home territory, the Chelans hunted game ranging from deer to marmots; gathered fruits, roots, and vegetables; and fished in both the lake and in local rivers. They burned off forested areas to encourage the growth of plants that would attract grazing animals; cooperatively drove deer, mountain goat, and other game into brush fences for slaughter; and used tunnel-shaped fish traps and other devices to maximize catches. The Chelan River was impassable to salmon due to its high flow rate and steep falls, but the tribe took non-migratory fish, including cutthroat trout, bull trout, and burbot from the lake. They had a legend to explain why salmon could not make it up to Lake Chelan:

"Coyote noticed the very beautiful daughter of a Chelan chief fishing for salmon in Lake Chelan, so he decided to ask for her hand in marriage. When Coyote asked the girl's father if he could marry his daughter the chief refused in no uncertain terms. This so enraged Coyote that he immediately threw huge boulders into the Chelan River. The boulders created rapids and falls that have ever since prevented the salmon from navigating upriver to the lake" (Wapato Heritage)

It cannot be determined how large the Chelan Tribe was before its numbers were reduced by smallpox, measles, flu, and other diseases, but in 1850 there were about 250 living along the Columbia River and 1,185 in villages on the lake. Within just 20 years, by 1870, their numbers were believed to have been reduced to fewer than 300.

Treaties and More Treaties

The first non-Indians to live in the Chelan and Wenatchee valleys were prospectors and miners, many of them Chinese, who arrived as early as 1863 to search for gold. They were subject to frequent attacks by Indians, and in 1875 it was reported that up to 300 Chinese miners died in a single massacre. Others carried on until rampant anti-Chinese sentiment among white settlers in the 1880s led to the murder of some and the expulsion of all.

Lake Chelan proper was not settled by non-Natives until near the very end of Washington's Territorial days, in part because of its isolated and difficult location. A second reason was complications flowing from the government's efforts to put Indians on reservations and take their land for settlement, which often left the title to that land in dispute. Treaties were made and abrogated, reservations established and rescinded. Land fell into and out of tribal ownership. Many Indians simply refused to live on the reservations, staying put where they and their forebears were born.

Isaac Ingalls Stevens (1818-1862), Washington's first Territorial governor and superintendent of Indian affairs, was tasked with negotiating treaties that would move Natives to reservations and free up land for American settlement and exploitation. He was energetic and committed, and he went about his work with enthusiasm and guile. Whether they agreed or not, several tribes, including the Chelans, were considered by Stevens to be participants in the 1855 Yakama Treaty negotiations that established the Yakama Reservation. (An Indian Claims Commission opinion more than 100 years later backed Stevens, ruling that the Chelan, Entiat, Wenatchee, and Columbia Indians were all included under the name "Pisquouse" in the treaty document.) But many simply refused to be bound to reservations or to leave their traditional areas, and many of those ended up banding together under the Columbia Sinkiuse chief, Moses (1829-1899), who rejected the treaty.

Moses and his followers fought occasional skirmishes with authorities, but they largely remained aloof, neither overly friendly nor openly aggressive, an enigma rather than an imminent threat. In 1877, although torn by loyalty to his ally and friend, Chief Joseph (1840-1904), Moses abstained in the war between the U.S. and Joseph's Nez Perce. But he was under steady pressure to move onto either the Yakama or the later-established Colville reservations, and he wanted neither.

In 1879 the federal government gave up, and President Rutherford B. Hayes (1822-1893) created the Moses Reservation (also called the Columbia Reservation) on a huge swath of land that started north of Lake Chelan and stretched to the Canadian border. Later that year a small contingent of U.S. soldiers under the command of Colonel Henry C. Merriam (1837-1912) built a sawmill and a small fort called Camp Chelan where the lake empties into the Chelan River. They were the first non-Indians to inhabit that site, but did so for less than a year before leaving to establish Fort Spokane.

After the army abandoned Camp Chelan in 1880, the Moses Reservation was extended by executive order to include all of Lake Chelan, including where Merriam's camp had been and where the town of Chelan later would be sited. This, at least in theory, protected the area around the Chelan River from white settlement. In 1883, a 15-mile-deep strip along the Canadian border, rich in minerals, was withdrawn from the reservation by executive order after negotiation with Chief Moses. In 1883 or 1884, the federal government again negotiated with the chief, this time for the surrender of the remainder of the Moses Reservation. It was a controversial bargain, one that brought Moses personal gain in the form of an annuity, and he would be harshly criticized by many for trading away Native land.The rescission of the Moses Reservation was officially ratified by Congress in 1886.

Moses and most of his followers, including the Chelans, moved to the Colville Reservation, and President Grover Cleveland (1837-1908) opened the former reservation land at the south end of the lake to "homesteads." The seemingly innocuous use of this word would before long greatly complicate efforts to found a town where six years earlier Camp Chelan had briefly stood.

The Hard Way In

Also in 1886, William Sanders (b. 1861) and Henry Domke (often spelled "Dumpke" and "Dumke" in older sources) arrived at Lake Chelan after an arduous trek from the north. They had traveled down the Columbia and then up the Methow River to the top of a mountain divide, from where they could see the lake. As they tried to work their way down to it, their only horse fell over a cliff, taking along their supplies. The men subsisted on fish caught from streams until they finally managed to reach the lake shore.

Sanders and Domke built a crude boat and made it safely to the south end of the lake where it empties into the Chelan River. There they were greeted by Chelan and Entiat Indians from Moses's band who had not moved to the Colville reservation and had either taken 640-acre allotments granted as part of the agreement that terminated the Moses Reservation or had simply refused to leave their ancestral land. Sanders and Domke got on well with the Indians and decided to settle there.

Sanders was at Chelan to stay, but Domke, said to be a dreamer, was not. He managed to talk a Portland firm into selling him a portable sawmill on credit, which was dragged up to the lake and erected at a place he named Domke Falls. It was not a success -- the most widely reported story is that when Domke diverted water into the mill, the machinery actually ran backwards. No lumber was ever cut there, and the mill was repossessed and removed. Domke, discouraged, moved away and disappeared from the Chelan story. William Sanders stuck it out, and was present to greet additional settlers who started to trickle in. He eventually started a successful dairy farm on the lake.

Ignatius A. Navarre (1846-1919) and Lewis H. Spader (1857-1931) also arrived at Chelan in 1886. Navarre had practiced law in Seattle and later was a probate judge for Yakima County. From 1882 to 1885 he worked as a government surveyor in parts of what are now Douglas, Chelan, and Okanogan counties, and he may have visited south Lake Chelan as early as 1884. What is known for sure is that in 1886 Navarre filed a homestead claim just a few miles away from the Chelan River on the lake's south shore. His wife, Elizabeth Cooper Navarre, became the first white woman to settle permanently on Lake Chelan (Colonel Merrian's wife and children had accompanied him during the short life of Camp Chelan). The Navarres' only son, Joseph (b. 1889), was indisputably the first white child born on the shores of the lake.

Born in Turmoil

The convoluted history of the Moses Reservation and the 1886 allotments of land to some tribe members was soon to stymie the first attempt to create a town of Chelan. President Cleveland's 1886 order dissolving the Moses Reservation had opened the land at the south end of the lake for homestead purposes only. In July 1889, Okanogan County Probate Judge C. H. Ballard filed a plat for a town at the site of the short-lived Camp Chelan with the land office in Yakima (at least one source says Waterville).

The plat was accepted, but should not have been -- the land could not legally be platted as a townsite because its use was restricted to "homesteads" by President Cleveland's order. And now it could not legally be used for homesteads, because homesteads were not permitted on property platted as a town, and the plat had been accepted and recorded. This put everything into legal limbo. By the time the magnitude of the mess was discovered, Ballard had sold more than 1,000 lots for $5.75 apiece.

Straightening out this absurdity took an act of Congress, which came in 1892 when it granted a federal "patent" for land that included the property Ballard had chosen for the townsite. This had the desired effect of reversing President Cleveland's homestead limitation, but created a whole new problem. To grant such a patent, Congress had to make a formal finding that there were no "adverse claims" to the land, and it did so. But, of course, there were adverse claims -- those of Indians who had taken allotments rather than move to the Colville Reservation, and that of at least one Native, Long Jim (the hereditary Chelan chief), who had refused to take an allotment, relying instead on a claim that his father, Chief Innomoseecha, had never ceded his ancestral land and that Chief Moses had no authority to do so. The most problematic issues involved his land, which was very near the townsite boundary, and that of Chelan Bob and Cultus Jim, both of whom lived downriver on allotments near Chelan Falls.

Eight white settlers soon forcibly took possession of the Indians' land. In one particularly egregious incident, a newcomer from Canada, Alfred William LaChapelle (1846-1943), "drove Chelan Bob and Cultus Jim away, appropriated their crops to his own use, and made complaint that the Indians were dangerous characters" (Illustrated History of North Washington, 676). The two Indians were briefly jailed, and the state land office ruled in favor of the settlers. But U.S. Secretary of the Interior John Willock Noble (1831-1912) overturned that ruling in 1893 and ordered the land returned to the Indians. His successor, Hoke Smith (1855-1931) ordered federal troops to oust LaChapelle and the seven other white settlers, but this action was enjoined by Washington's first federal circuit court judge, Cornelius Holgate Hanford (1849-1926).

Hanford, however, allowed the federal government and the Indians to sue to eject the settlers, and when this suit was heard, he vindicated the rights of Long Jim, Chelan Bob, and Cultus Jim. As explained in a newspaper of the day:

"According to a decision handed down by Judge Hanford, of the United States Circuit court, in May, 1897, three square miles of cultivated lands in the vicinity of Lake Chelan, then occupied by white families, reverted back to Indians. The action was brought in the name of the United States against A. W. LaChapelle, but with this were consolidated seven other suits. The decision of Judge Hanford applied to all of them ... .

"The matter has been in constant litigation since 1890 ... . Two of the Indians, Long Jim and Chelan Bob, were born on the land formerly occupied by them, and the wife of Cultus Jim was born there. They testified that their fathers' fathers had land there for generations. The testimony was that the whites came in 1890. Prior to that time the rights of the Indians had been respected by the whites in that locality … , the Indians refusing tempting offers to buy them off" (The Spokesman Review, quoted in Illustrated History of Stevens, Ferry, Okanogan and Chelan Counties, 676).

Native Americans did not always fare so well in disputes with white settlers and state authorities, but this ruling put to rest the last of the competing claims and confusions at Chelan. The town, legitimized by the 1892 act of Congress, could now reach whatever its potential was to be, with white settlers and the few remaining Indians living side by side on land they owned.

Starting a Town

Although today Chelan is famed as a recreational mecca, it was the quest for riches that first brought waves of newcomers to the lake's shore. Gold, silver, copper, and other minerals were to be found in abundance; Ponderosa pine and Douglas fir blanketed the surrounding mountainsides; a limitless supply of pure alpine water was on tap for consumption, irrigation, and later, power generation. Chelan's early settlers did not wait for arcane legal complications to be resolved before putting in place those things that make a town.

The pioneering families were soon joined by other settlers, at first very few. In April 1888, the families of Captain Charles Johnson (1842-1912), Benjamin F. Smith (b. 1858), and Tunis Hardenburgh (1832-1898) settled on the south end of the lake about a mile west of the Chelan River. This site was first called Lake Park, then Lakeside, and until 1956 existed as a separate town. Lake Park would become the settlers' first industrial center because the depth of the water there, unlike at the entry to the Chelan River, was sufficient for boats and log booms.

Later in 1888, L. H. Woodin and A. F. Nichols opened a sawmill at Lake Park that, unlike poor Mr. Domke's, proved to be a useful and profitable enterprise. Mill equipment was brought up the Columbia by steamship, then carried by horse from Chelan Falls overland by local Indians, including those known to the whites as Long Jim, Cultus Jim, Crooked Mouth Bob, Wapato John, and John's son, Sylvester. The mill was the first of several on the lake that would supply virtually all the lumber with which the early communities would be built.

Just east of Lake Park, at the Chelan townsite, a post office was established in 1890. At that time there were more than 300 rough buildings there, mostly thrown up merely to preserve claims to lots. By the next year three general stores, a hardware store, a drug store, two saloons, and a blacksmith's shop were up and running.

The first true residence (as opposed to the earlier shacks) on the Chelan townsite was built by Thomas R. Gibson during this time, and by late 1891 a local paper could boast (albeit in ignorance of the full extent of the legal problems that lay ahead):

"Over two years ago the present site of the town was platted and it has had a steady growth ever since. A new town only a mile up the south shore has been laid out within a year and named Lake Park, where the steamers land, and it is a beautiful situation. The two places together have five stores, three hotels, one sawmill, one market, one or two real estate offices, a good livery stable, two church organizations, and a live Sunday School" (Chelan Falls Leader, November 19, 1891).

Trails, Rails, Roads, and Boats

From times long past through the early days of non-Indian settlement, the primary means of reaching Lake Chelan was on trails, some blazed by Indians, others trampled down by the habitual passage of wildlife. The Columbia River was less than four miles from the lake, but passage between the two at their nearest point was exceedingly difficult. One prominent foot trail ran from Navarre Coulee on the Columbia northeast about seven miles to the south end of the lake, and this was used most frequently by the earliest settlers. Other trails pierced the forest at the north end of the lake, from which the settlements to the south could be reached by boat.

The City of Ellensburg, the only steam vessel operating on the upper Columbia River from 1888 to 1897, and James J. Hill's (1838-1916) Great Northern Railroad, completed in 1891, both brought travelers near, but not to, Lake Chelan. Not until 1914 did the railway extend up to the mouth of the Chelan River, where Chelan Station was built on the north shore, still several miles from the lake.

As part of the short-lived Camp Chelan project, the army in 1879 had cut a circuitous wagon road that linked the camp to White Bluffs far to the south in what is today Benton County. The last three miles of this road was a steep stretch up the north side of the Chelan River gorge. In 1891 a Chelan Falls pioneer, Laughlin MacLean (1856-1910?), carved a second wagon road to the lake, this one along the south side of the gorge. For the next 40 years, these two roads would provide the primary access to the lake from the south. A young boy traveling from Chelan Station to the lake in 1915 described the frightening last leg of the trip:

"My mother, sister and I were all eyes when we got off the train at Chelan Station and looked at that hill opposite the river. Where we came from, anything over a 1/2 percent grade was called a hill ... . The ChelanTransfer picked us up ... . It was pulled with a four-horse team. I can still hear the teamster’s commanding voice as the traces came tight with a jerk and we started up. When I say up, I mean up ... . The horses’ bellies were not far off the ground ... on the second switchback I looked back and down and I’ll swear it was a 100' of nothing. I was the most frightened five-year-old boy in the state of Washington" (Barkley).

A wagon road connected the towns of Chelan and Lakeside, and in 1889 a wooden bridge was built that spanned the Chelan River where it left the lake, joining the settlements on either side. In later years, additional rough roads would be cut, but well into the twentieth century, Chelan was not an easy place to get to. Plans by the Chelan Railroad & Navigation Company in 1903 to build an electric railway from the Columbia River to the town never materialized, and no passenger rail line would ever reach the lake.

Growth, Governance, and God

One of the earliest organizations established in Chelan was a Board of Trade, and it touted the area's attractions in an 1891 brochure intended to draw others to settle there:

"Future Metropolis of Central Washington With Immense Water Power ... Unlimited Resources ... A Manufacturing Center ... Healthful Climate ... Magnificent Scenery and the Finest Pleasure Resort in America" ("Cultural Resources Overview and Research Design," p. 5-40).

That year on January 3 The Chelan Leader published a list of businesses located in Chelan that included three general merchandise stores, a hardware store, a blacksmith, an undertaker, a printer and newspaper, a bank, a hotel, a saloon, a doctor, and a dentist, among others.

A failed attempt to incorporate the town in early 1893 did nothing to slow its growth, but the national financial panic that started that year did. Despite the crisis, Chelan did better than many, blessed as it was with natural beauty and abundant resources. But access to the lake and the new town at its southern end remained difficult.

Starting even before the full resolution of the problems caused by the original plat, the Chelan townsite was steadily enlarged, with plat extensions filed in 1891, 1892, 1898, 1901, and 1902. In May 1902, the male citizens (women did not yet have the vote) voted by a margin of 56 to 7 to formally incorporate the town. Amos Edmunds (1849-1923) was elected Chelan's first mayor and John Albert Van Slyke (1857-1932) became town treasurer. They were joined by a five-member city council.

In 1894, town residents were presumptuous enough to file a petition to move the official seat of what was then Okanogan County from Conconully to Chelan. The proposal was not put to a vote at that time, but resurfaced again in 1898. This time a vote was taken, and the measure lost, 530 to 253, the margin attributed to widespread speculation that the boundaries of Okanogan County would soon be altered and the issue thus moot. This occurred the following year, when the legislature created Chelan County from portions of Kittitas and Okanogan counties, effective November, 1900. The legislation designated Wenatchee as the new county's seat, forever thwarting Chelan's governmental ambitions.

In Chelan, as in most small towns across America, religion was given its full due. The first, non-denominational Sunday school opened August 11, 1889, held on an outdoor platform. A Congregational Church was started in 1890, followed by Methodist Episcopal (1891), Catholic (1904), Seventh Day Adventist (1905), and Church of the Nazarene (1914). One early church building, St. Andrews Episcopal, was designed by noted Spokane architect Kirtland Cutter (1860-1939) and built in 1898 using logs towed from the northern reaches of the lake and milled at Lakeside. It is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Public entertainment was a scarce commodity, and in 1893 a group of local women contacted the Chautauqua Circle of New York, an organization that brought teachers, preachers, entertainers, and speakers to rural areas throughout the country. A Chelan chapter was established on June 30 of that year, and for nearly four decades it would bring a wide variety of entertainment and educational features to the town, not finally disbanding until 1932, during the depths of the Great Depression.

Water, Tourists, and Roads

During the twentieth century, Chelan developed in much the same manner as other rural communities in the West, enjoying periods of boom punctuated by episodes of bust. The area's timber and mineral resources were eventually all but exhausted, but its third great resource, water, has played a vital and continuing role. In significant ways, the past and present story of the city of Chelan is found in its relationship to the waters of the lake from which it takes its name.

Attempts to dam the Chelan River near Chelan date back as far as 1889, when L. H. Woodin, hoping to provide a steady supply of water to the new town, impeded the river's flow with a rickety wood structure about a half mile downstream. This was washed away by the next spring flood.

Later dams would serve to irrigate agriculture, alter the level of the lake, and, eventually, provide hydroelectric power. The first dam built specifically to raise the level of the lake was completed at the foot of Chelan's Emerson Street in April, 1892. Called Buckner Dam, it raised the lake by several feet, inundating some low-lying areas but providing water to other properties, increasing their value considerably. Just a month later, work was started on a 6,000-foot flume for the new Chelan Falls Water Power Company. But the project's chief financier, David W. Little (1851-1892), soon died, a late-spring flood damaged both the flume and Buckner Dam, and the financial Panic of 1893 hit -- a triple blow that brought all work to a permanent halt.

In January 1893, the larger and stronger Ben Smith Dam was built by the Chelan Water Power Company, designed to raise the level of the lake enough to allow steamships to moor at Chelan. Although this new structure was built to withstand the normal seasonal variations in lake levels, Mother Nature had a nasty surprise in store. In June 1894, massive spring floods fed by the melt of record snowfalls swept away this newest structure and caused damage up and down the lake and beyond. As described by an early resident:

"The massive flood raised the lake level 11 feet over the 1892 low water mark ... [and] changed the course of Fish Creek endangering Moore's Hotel ...; inundated the whole main street of Lake Park until the steamers could land at the front porch of the Lake View House; washed out and caved in the Chelan River below town until it sounded like thunder and felt like earthquakes; rechanneled a fourth of a mile of the mouth of the Chelan River; and washed away and moved around many buildings in Chelan Falls" (Lake Chelan in the 1890s).

Power Generation

After that cataclysm there seems to have been little more done with the lake or the river until 1901. Morrison McMillan Kingman (1859-1938) purchased the Chelan Water Power Company in early 1899, and he joined with the town to build a dam on the river that, by May 1903, was providing the area's first regular and substantial supply of electricity. Another dam was built that year to raise the level of the lake and once again allow ships to moor at Chelan. These facilities, under various ownerships, would reliably serve the area for more than two decades.

The Chelan Electric Company, a subsidiary of the Great Northern Railroad, purchased the Chelan Water Power Company in 1906. Over the next two decades it carried out studies for a new Chelan River dam, but built nothing. In 1925, its interests were sold to the Washington Water Power Company, a private firm with headquarters in Spokane. In early 1926 Washington Water Power was granted a 50-year federal license to construct a new dam and powerhouse on the Chelan River. Work began in April, and at its peak the project employed 1,250 men, housed in four camps. Most crews worked on the dam, intakes, tunnel, and powerhouse, but others were sent to clear the shores of the lake of brush and trees in anticipation of a considerable rise in water level upon completion of the project.

The steel-reinforced concrete dam was built about one-half mile downstream from where Lake Chelan enters the river, within the town limits. Its primary purpose was to divert the river's flow into two intakes that funneled into a 10,694-foot long, 14-foot wide tunnel (bored mostly through solid granite) that ends in two generating turbines at the powerhouse on the southwest bank of the river near Chelan Falls. The first generating unit was put on line in September 1927, followed by the second 11 months later. When the project was completed in 1928, it was the largest electrical-generating facility in the Northwest and brought many benefits to the Chelan Valley and other areas, including Coulee to the east and the Okanogan Valley to the north.

Now operated by the Chelan County PUD, the Chelan Dam and its powerhouse remain an important source of power in the county and have barely changed in the 84 years since they were completed. But the dam also raised the lake's level by 21 feet, inundating vast areas of shoreline, with ill effects. Some of these consequences were catalogued in a later study:

"The project provided no mitigation for the loss of fish runs, the inundation of wildlife habitats, or the disruption of traditional native use of the lakeshore or river gorge. The Chelan River channel became dry during much of the year, as the water was rerouted through the power tunnel to the powerhouse below. Private property ownership was affected all around the lake, as the water level rose 21 feet in the summer and fall of 1927" ("Cultural Resources Overview and Research Design," p. 5-53).

Irrigation

Major efforts to enhance irrigation in the southern reaches of Lake Chelan were generally part of larger projects affecting a wider geographical area. Although there is some agricultural activity within Chelan's city limits, including vineyards and orchards, most of the farms at the lake's southern end are located about eight miles north, near the town of Manson.

Much of the land in south Lake Chelan best suited to agriculture was still owned by local Indians in the early 1900s, and federal law prohibited its sale. This changed in 1906 when Congress passed legislation permitting the disposal of all but 80 acres of each Native allotment. Almost immediately, a consortium of private investors incorporated the Wapato Irrigation Company and began buying up properties about seven miles north of the entrance to the Chelan River. Tapping nine creeks and two lakes north of the town of Manson, the company built six miles of canal and wooden flumes to carry the water to a reservoir at Antilon Lake, whose outlet was dammed to create a reservoir. Water from the system was first delivered to area users in 1911.

The provision of water was tied closely to land speculation. The irrigation company's real estate was conveyed to the Lake Chelan Land Company, which bought additional land and marketed five-acre orchard plots to settlers with claims "that five acres would make a man an independent income, and twenty acres would make a man a fortune" ("Cultural Resources Overview and Research Design," p. 5-48).

By late in the second decade of the twentieth century, both the land company and the Lake Chelan Water Company (which now owned the water rights) were in deep financial trouble. When the former declared bankruptcy, local orchardists formed the Lake Chelan Reclamation District, which could sell bonds and levy taxes on land to finance its operations. Over the ensuing years, the district expanded and improved its irrigation network and is still (2012) an active entity.

Recreation

Word of the natural beauty of Lake Chelan spread early, and by the late 1800s tourism already was a major source of revenue for the town and the region. Facilities to house visitors sprang up at Chelan, Lakeside, and Stehekin to the north, and tourists flowed in, primarily from west of the Cascades. There were guest accommodations in place as early as 1892, and in 1901 at Chelan, Clinton C. Campbell (1855-1938) built the Campbell Hotel, renamed the Chelan Hotel in 1904, and still in business today (2012) as Campbell's Resort. Campbell's original hostelry charged 50 cents per night for a room and the same for dinner. It was just one of several tourist hostelries to open on the lake's south end during the first decade of the new century. Marking the new year in 1904, The Chelan Leader boasted:

"The tourist travel to the lake has far exceeded that of any previous year, taxing to their upmost capacity all the hotels and resorts. The public park has been plowed and fenced and will be planted to trees next spring. A fine, costly, well-equipped sanitarium is one of the acquisitions of the year. Taken altogether the Lake Chelan community has made a decided advance over any previous year in its history" (The Chelan Leader, January 1, 1904).

The summer climate at Chelan offered respite from the cooler and wetter weather found west of the Cascades, and the lake and surrounding areas offered recreational opportunities including fishing, boating, hiking, and simple sunbathing. Although somewhat depleted in later years, the fishing at the lake was once considered some of the best in the world.

Through the Years

The growth of the city of Chelan has been constrained over the years, first by inaccessibility and later by terrain, water, and neighboring communities. It grew, not by leaps and bounds, but incrementally. The single biggest increase in population occurred between 1920 and 1930, when the first roads opened, work on the Chelan Dam drew workers from far away, and the number of inhabitants grew from 896 to 1,403. From that point on, population growth was more gradual, hitting 2,445 in 1950, 2,802 in 1980, 3,526 in 2000, and 3,890 in the most recent census (2010). Oddly, although Lakeside merged with Chelan in 1956, that decade saw the city lose population, albeit only by 43 souls.

The economy of the city is, and has been for decades, dominated by tourism, and this is likely to hold true for decades to come. In the earlier years of the twentieth century, a few sawmills, and box factories that primarily made shipping boxes for local growers, provided additional employment and income for the town. One local business, the Chelan Transfer Company, proved an enduring success, providing stage service in the town's early days and still doing business in the twenty-first century.

There simply do not exist the space, transportation links, or infrastructure to support large industries in Chelan, although the local economy is bolstered by commercial orchards, vineyards, and several wineries. Immigrants from Italy were known to have cultivated wine grapes on south Lake Chelan as early as 1891, apparently for their own consumption. Commercial growing came later, and started with juice grapes in the late 1940s, with over 150 acres under cultivation in Chelan and nearby Manson growing grapes for the Welch company. The first commercial wine-production vineyard opened in 1998, and by 2006, 140 acres of the Chelan Valley were devoted to growing grapes for wine.

A devastating tragedy struck the town on November 26, 1945, when a bus carrying 20 school children heading to Chelan went off the road and plunged into the lake. Fifteen students and the driver drowned. When the bus was raised, only six bodies were inside. Due to its depth, Lake Chelan has earned a reputation of never surrendering its dead, and the remains of the other nine fatalities were never recovered. It remains the single worst school-bus accident in state history.

Despite its well-deserved reputation as a recreational wonderland, Chelan has since the completion of the Chelan Dam had one major environmental eyesore -- an almost always dry riverbed stretching from the downstream wall of the Chelan Dam all the way to the powerhouse at Chelan Falls. What once had been a rapidly flowing wild river was tamed by progress into nonexistence, leaving a dramatic and precipitous gorge with nothing but rocks at the bottom. Under the term of the original hydropower license, no lake water was required to be released into the river, which would act only as an overflow canal for the dam. Such overflows rarely occurred, and almost never in sufficient volumes to restore the river even briefly.

As part of its relicensing in 2004, the PUD submitted a plan to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission and the state that once again made the river flow, largely by pumping water that had already been used to generate electricity back up to the head of the river's lower reach. A primary goal was to provide habitat for cutthroat trout, but members of the United Tribes of the Umatilla Reservation thought the flow insufficient, and appealed the decision. The appeals board agreed that the plan did not ensure that water quality standards would be met, but upheld it as a rational balancing of the competing interests. Today (2012) the long-dry river once again runs year-round, although its long-term effect on the fish populations remains to be seen.

Chelan Today

Known throughout Washington and beyond as a prime vacation destination and summer-home site, Chelan today (2012) sees thousands of vacationers in both summer and winter, drawn by recreational activities on land and water. The summer influx of vacationers can swell the city's population to more than 25,000.

Whites and Hispanics today make up more than 96 percent of Chelan's permanent population. Median household income nearly doubled in the city between 2000 and 2010, from $28,000 to nearly $53,000, still slightly below the state average. For full-time residents, the town has three public high schools, three elementary schools, and a full range of businesses and support services.

Chelan has proved sensitive to the vagaries of the national and regional economies, but its magnificent setting and wide range of accommodations and recreational offerings have carried it through the tough times. The city works constantly to improve its facilities and infrastructure while preserving and protecting its long heritage. In 2012, the Historic Downtown Chelan Association and the City of Chelan were recognized as an "Outstanding Partnership" by the Washington Main Street Program, cited for their efforts in "maintaining and enhancing the charm, safety, livability, and history of Chelan’s downtown core" ("Awards and Accolades").