On Saturday morning, January 20, 1917, a fire is reported in the Grand Theatre at 3rd Avenue and Cherry Street in downtown Seattle. The five-story brick building was built in 1900, before the era of steel-frame construction in Seattle, and is essentially a firetrap. The blaze starts beneath the floor of the balcony and before the fire department arrives, the entire upper portion of the building is fully involved. Firefighters enter the third- and fourth-story fire exits with hose lines and proceed to knock down the flames. But the fire quickly destroys the wooden trusses holding aloft the mansard roof and the roof collapses into the theater, taking with it the gallery, balcony and the hose crews. Nine firefighters are rescued and survive the mishap, but Battalion Chief Frederick G. Gilham (1864-1917), age 52, is lost amid the burning rubble. He is eventually rescued but dies from his injuries en route to the hospital. The Grand Theatre, its interior totally gutted, will remain vacant and unused until March 1923 when it will be sold and converted into a multilevel, 350-car, parking garage.

Seattle's Foremost Playhouse

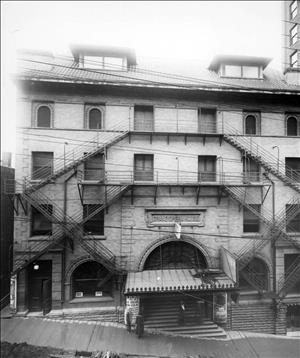

The Grand Theatre (formerly the Grand Opera House), located at 217 Cherry Street, was constructed in 1900 for theater impresario John E. Cort (1861-1929). It was designed by Seattle architect Edwin Walker Houghton (1856-1927), a well known designer of commercial buildings, playhouses, and theaters. When the Grand Opera House opened in 1900, it was considered Seattle’s foremost playhouse with seating on three levels for 2,200 people. The opera house was damaged by fire on November 24, 1906, but quickly repaired and reopened for business on December 9, 1906. Bigger and more lavish playhouses were being built uptown and Cort abandoned the Grand in 1907 to make the new Moore Theatre, located at 2nd Avenue and Virginia Street, his flagship.

In 1911, Cort leased the Grand Opera House to motion picture and vaudeville magnate Eugene Levy (1878-1970). Levy already managed six popular theaters in Seattle and six others in Tacoma and Spokane, and converted it into another movie/vaudeville house. Renamed the Grand Theater, seats were only 10 cents for evening shows and a nickel for Saturday matinees.

Fire!

Early Saturday morning, George Nishimura, the theater’s janitor, was working on the main floor when he saw light flickering on the stage’s reflective curtain. He went onto the stage, looked up and saw fire in the center of the balcony. Nishimura rushed to a fire box inside the playhouse and turned in the alarm at 6:13 a.m. Although the theater was empty, it abutted and was connected to the Hotel Rector (now the St. Charles Hotel), 619 3rd Avenue, through a doorway at the balcony level.

A full first-alarm response brought three engine companies, two ladder companies, a squad wagon and Battalion Chiefs William H. Clark and Frederick G. Gilham to the Grand Theater. Upon arrival, firefighters discovered the entire upper portion of the building was fully involved and fire had spread upwards into enclosed spaces. Ten minutes later, Seattle Fire Chief Frank L. Stetson (1855-1943) arrived at the scene from Headquarters/Station No. 10 and took command of the general operation. Chief Gilham was put in charge of fire fighting on the upper floors of the theater and Chief Clark supervised efforts to protect the surrounding buildings.

Seattle Police motorcycle officers Clarence H. Shivley and John J. Kush, dispatched to the Grand Theatre at the first alarm, assisted desk clerks Arthur Price and Carl Holbrook to rouse and evacuate the guests from the Hotel Rector’s 105 rooms. Scores of other police officers cordoned off the area and redirected traffic.

Disaster

Hose crews gained access to the third and fourth floors through the fire exits on the Cherry Street side of the building. Above the fourth-floor gallery was a garret with two dormers designed to provide ventilation for the cavernous theater. At about 7:00 a.m., the wooden trusses supporting the mansard roof gave way, bringing down tons of debris onto the gallery, balcony and theater floor, along with the hose crews. Chief Stetson immediately sent in a second alarm and help arrived from nearby fire stations within minutes. Rescuers located nine firefighters amidst the burning wreckage and carried them outside to safety, but Battalion Chief Gilham was missing. The injured men were transported by ambulance to nearby hospitals for medical attention.

Chief Gilham was last seen standing on the fourth-floor fire-escape landing when the roof collapsed. He called for another hose line and then disappeared into the building to find his crews. Chief Gilham apparently became lost in the heavy smoke and fell from the gallery level into the burning rubble covering the balcony. Trapped by the debris and unable to call for help, he was not found by rescuers for almost half an hour. Chief Gilham was severely burned and suffering from other injuries, but still alive. Tragically, he expired in the ambulance from shock and burn trauma en route to City Emergency Hospital at 4th Avenue and Yesler Way. At Chief Stetson’s direction, the body was removed to the Seattle Undertaking Company, on 5th Avenue near Pine Street, to prepare for burial.

With the roof gone, the heat and smoke vented and the fire was promptly brought under control and “tapped out” shortly before 8:00 a.m. The subsequent investigation by Seattle Fire Marshal Harry W. Bringhurst (1861-1923) and Fire Inspector John Reid (1885-1951) determined the blaze had been caused by faulty wiring beneath the floor of the balcony. Damage to the building was estimated at $45,000.

Frederick Gilham, Firefighter

Battalion Chief Frederick G. Gilham, age 52, had been with the Seattle Fire Department (SFD) for 24 years. He came on the job June 28, 1889, immediately after the Great Seattle Fire of June 6, 1889. He resigned in 1896 to prospect for gold in Alaska and returned to the fire department in 1899. He was promoted to the rank of lieutenant in 1901, captain in 1904 and battalion chief in 1913, commanding SFD Station No. 2, located on the NE corner of 3rd Avenue and Pine Street (today Macy’s Department Store).

Between 9:00 a.m. and 11:30 a.m., Tuesday, January 23, 1917, Chief Gilham’s body lay in state at SFD Headquarters/Station No. 10, at 3rd Avenue S and S Main Street, where thousands of people viewed the casket. A funeral cortege, headed by the fire department band, followed the hearse carrying Chief Gilham’s casket to Station No. 2, from which he made his last run, and then to the First Presbyterian Church, located at 7th Avenue and Spring Street. His public funeral, officiated by Reverend Dr. Mark A. Matthews (1867-1940), was attended by Seattle Mayor Hiram C. Gill (1866-1919), numerous city officials, uniformed firefighters and police officers, and hundreds of personal friends. After the funeral service, the cortege, one of the largest seen in the city, proceeded to Lake View Cemetery on Capitol Hill where Chief Gilham was interred. He was survived by his wife, Madeline, two adult children, Ruth and Brian, and brother, Captain Charles W. Gilham, a firefighter assigned to Engine Company No. 6.

The Curtain Falls

Eugene Levy, intending to restore the Grand Theatre to its former glory, temporarily moved his vaudeville bookings to another playhouse he had just leased. Over the years, the Grand had been inspected numerous times by the Seattle Fire Department and Department of Buildings and many improvements had been made to bring it up to code, including additional fire exits, fire escapes and an asbestos stage curtain. But the wood-frame building was obsolete. Now that it had been gutted, the restored structure would be required to meet all current building and fire codes at significant expense.

Meanwhile, John Cort was busy managing the Moore Theatre (built 1907), and Eugene Levy took over management of the Orpheum Theatre (built 1911) at 3rd Avenue and Madison Street in June 1917. The Grand Opera House was ignored and the burned-out building remained vacant and unused until March 1923, when it was purchased by the Griggs Garage Company and renovated at a cost of $60,000.

Renamed the Cherry Street Garage, the new multilevel parking facility, with a capacity of 350 automobiles, was deemed to be the “largest, finest and best-arranged garage in the Northwest” (“Huge Garage Opens”). Company president Bruce Griggs boasted the facility was a full-service station, with gasoline pumps, automobile repair shop, parts department, and wash rack. Today (2012) the Cherry Street Parking Garage, listed in the Department of Neighborhood's catalog of historical sites, is owned and operated by Diamond Parking Inc.

Injured Firefighters

- George A. Boyd, Engine Company No. 10

- Lawrence Brunson, Squad Wagon No. 1

- Albert B. Colburn, Squad Wagon No. 1

- Charles A. Hull, Engine Company No. 10

- John Loughran, Engine Company No. 10

- Gordon W. Martin, Engine Company No. 14

- John McGinley, Engine Company No.10

- Otto A. Rooney, Ladder Company No. 2

- Arthur A. Shaughnessy, Engine Company No. 1