This essay about the life and times of Seattle pioneer David "Doc" Maynard was written by Alice Evered, a student at Northshore Junior High School in Bothell, and was awarded a prize in the Junior Division, Historical Paper Category, of the 2009 Washington State History Day competition. Alice vividly traces Maynard's journey from Ohio to the Pacific Northwest, where he took a new wife and started a new life in a muddy and primitive enclave with the name of Duwamps. Doc Maynard was to contribute greatly to the eventual success of the city that, at his insistence, came to be called Seattle. Although other pioneers are often credited as the city's founding fathers, this essay makes clear that without the unstinting efforts of Doc Maynard, Seattle would not be what it is today, and may not have been at all.

An Uncommon Man

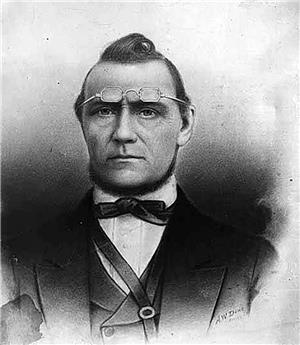

Some men strive for money, some for prestige. Others are content to hide in the shadow of more powerful people. There is still another, rarer sort of human being. This man is selfless, compassionate, and whole-hearted. One of these exceptional individuals in history was David Swinson Maynard, known to everyone as Doc.

Doc Maynard was born 1808 near Castleton, Vermont, into a generation of Oregon Trail travelers, treasure-hungry 49’ers, and adventurous Northwest settlers. After raising a family in Ohio, he began a second fateful chapter of his life, one that started in a little settlement casually referred to as Duwamps and ended in a thriving city now sporting the respectable name of Seattle, Washington.

A Fortunate Detour

The doctor did not plan to settle on Puget Sound. He set out in 1850 for the California Gold Rush, mostly to get away from a disloyal wife, whom he would eventually divorce. On the trail, he doctored a sick young widow named Catherine Simmons Broshears (soon to become his second wife). He promised the widow’s dying mother to deliver Catherine safely to her brother in Olympia.

Once Doc Maynard laid eyes on the beautiful land and bays of the Puget Sound, “California’s gold was gone for him forever” (Nelson, 7). His arrival in Seattle on March 31, 1852, set the stage for his many acts that would change the course of the town's history. Although other pioneers, such as Arthur and David Denny, William Bell, Charles Terry, and Henry Yesler, have been called the “founding fathers” of Seattle, Doc Maynard was to be the most influential Seattle settler. Maynard's unselfish work at crucial jobs and his genuine devotion to the young city left a legacy in the form of the city of Seattle.

A Man of Many Talents

Doctor Maynard was a busy man. Between his arrival in the Seattle area in 1852 and his death in 1873, he spent only about 20 years in Seattle. The amount of change he created in such a short time is truly unbelievable. Much of this resulted from the many essential jobs and positions he held in Seattle.

Maynard's business running a store first brought him to Elliott Bay. He had been living in Smithter (now called Olympia) since arriving in the Oregon Territory, and had set up a store there. He bought damaged goods from wrecked ships and was able to sell them at half the price of goods purchased from other merchants. Although the settlers liked this, other merchants, such as Mike Simmons (Maynard’s future brother-in-law) thought he was “a bad influence on the customers” (Morgan, 20). Thomas Prosch’s biography of Maynard, says:

“In the end, [the dealers] got rid of him, with the help of the great chief of the middle Sound Indians — Seattle” (Prosch, David S. Maynard and Catherine T. Maynard, 27).

That chief -- sometimes (later and incorrectly) called Sealth -- convinced Maynard without much trouble to move up the sound to a deeper bay. When Maynard arrived, Arthur Denny, David Denny, and William Bell were already settled on the place that was to become Seattle, but they wanted the doctor to settle near them “for the benefit a good man brings” (Morgan, 26). When Arthur Denny and Bell moved the southern boundaries of their claims north to make room for him, Maynard ended up with much of the land that downtown Seattle is on today (Arthur Denny, 41). Doc Maynard set up his store on this land and continued to sell his goods.

After a time, the settlers in the young community on Elliot Bay began to feel the need to fill some vital positions, such as judge. David Maynard was appointed justice of the peace by the Legislature in Oregon in July 1852. He performed the very first wedding in Seattle at Arthur Denny’s cabin, with Henry Yesler as the witness. The couple was David T. Denny and Louisa Boren. Maynard wed many additional couples and performed occasional other legal business, such as trials. He was also appointed King County's notary public by the Legislature. Without any legal training, Maynard took on these jobs for the good of the town, even sacrificing a honeymoon with his new wife to return to Seattle and marry other eager couples.

The Doctor and the Indians

Yet another position that the doctor filled was as Indian agent. Mike Simmons, Maynard's new brother-in-law, was Indian agent for the Washington area, and in 1885 he appointed Maynard to be in charge of the central Puget Sound Indians. In Skid Road, Murray Morgan writes:

“The doctor’s reputation as a healer rose steadily among the tribesmen, and the good will he acquired as a physician helped him as a diplomat” (Morgan, 43).

Maynard was soon told to move the Duwamish tribe to Bainbridge Island because of the hostile activity of some Natives. He managed to persuade 354 of the roughly 700 Indians to move, and stayed with them for more than six months. In a letter to his son, he writes:

“Although I have occupied the most dangerous post of any in the field, I have succeeded in quelling the spirit of war and established a friendly feeling with the determination to remain so” (Brewster, 110).

Of course, Arthur and David Denny also made an effort to protect their settlement from Indians by serving in the Indian War, David as a member of Company C and Arthur as the Company A lieutenant (Bagley, 71). However, Maynard went on to say in his letter to his son, the hostility of very many more Indians than the number he had appeased could have wiped out the white settlers completely. This demonstrates his importance as a peacemaker for early Seattle.

Maynard’s relationship with the Indians also resulted in the city’s name, “Seattle." When a local clerk referred to the township as Duwamps, after the Duwamish River, the need for a more distinguished and official name became clear. Maynard suggested the name of the Indian chief of six local tribes, with whom he had a special bond (Meeker, 180). Chief Seattle (sometimes incorrectly pronounced "Sealth") once said, “My heart is very good toward Dr. Maynard.” He also highly esteemed Maynard as a doctor for both him and his tribespeople (Rochester, 1). As a result of their relationship, another long-lasting legacy of Doc Maynard’s is the enduring name of his city, Seattle.

One Trade Too Many

Further confirmation that he sincerely wanted the town to succeed is the fact that Doc Maynard even became Seattle’s first blacksmith, despite having no training and apparently little skill. According to Murray Morgan, author of Skid Road:

“He wanted a blacksmith very much … and when none answered an advertisement he put in the Olympia Columbian he set up a blacksmith shop of his own” (Morgan, 30).

Maynard had never had any blacksmith experience or education, and blacksmithing is difficult work. However, he was not fazed by this and, “with his usual enterprise, he bought and installed a forge and tools” (Watt, 139). Luckily, one day in September 1853, a man by the name of Lewis Wyckoff commented from the doorway of the blacksmith shop on Maynard’s obvious inexperience (Watt, 139). When Maynard snapped, “Well, perhaps you think you can do better yourself!” Lewis replied, “Yes, I can for that’s my trade” (Watt, 139). By that night, Maynard had sold the land and tools to the low-on-cash Lewis Wyckoff for only $10!

Maynard frequently tried to recruit skilled and hard-working men in this way in order to strengthen the town. As Murray Morgan writes in Skid Road, Maynard planned the town “with the conviction that it would grow to be a great city” (Morgan, 26). He believed that a great city stems from great citizens of all different trades, and he tirelessly worked to fill the gaps.

A Doctor, First and Last

Through it all, Doc Maynard never abandoned his black medical bag. He was a trained medical doctor, having worked under the esteemed Dr. Woodward in Cleveland, and he constantly made use of his education. On the Oregon Trail, he had doctored the sick, mostly the many cases of cholera. In Washington, he continually treated the Indians, a major reason why they respected him so greatly. A passage in Skid Road states:

“Maynard moved among the Salish tribesmen, listening to complaints, passing out medicine, delivering babies. Indians came from miles around to be doctored by him” (Morgan, 42).

In Seattle, his medical skills were sorely needed. In 1863, Doc Maynard opened Seattle’s first hospital. He worked as the superintendent, surgeon, and physician, and Catherine, his wife, was his nurse. They treated injured loggers and millworkers from as far away as Kitsap County. Maynard, in the old-fashioned way, didn’t rely heavily on surgery and “depended largely on the most simple means ... ” such as fresh air, sanitation, a pleasant and cheerful atmosphere, and alleviation of pain (Speidel, 7). Maybe it stemmed from his compassionate way with people, but all through his life, despite whatever else he turned his hand to, Doc Maynard was first and foremost a doctor.

Credit Where Credit is Due

Other settlers such as Arthur Denny, David Denny, Henry Yesler, and even Charles Terry and William Bell are often named as the founders of Seattle because they were the first to own large businesses and settled claims of land in the area. But did any of them contribute as much time and effort to the community as David Maynard? Most of these young pioneers, at an average of 26 years of age, worked at one or two jobs, such as Charles Terry, who was a storekeeper and landowner. But it was the middle-aged Maynard, at about 42, who volunteered to do the undesirable jobs, such as moving and appeasing the Indians in the midst of the Indian Wars, or opening the first blacksmith shop.

Arthur Denny is frequently named as the sole founder of Seattle because of the land he owned and the valuable governmental work he did. But Denny’s term as a delegate in the territorial congress kept him in Olympia for a good seven of Seattle’s early years. According to Clarence Bagley, author of Pioneer Seattle and its Founders:

“When he went away Seattle was a little village of little more than a score of families, but on his return he found it a thriving, bustling town, and that his lands had already made him immensely wealthy” (Bagley, 72).

This shows that, despite the accomplishments he was making in Olympia, Denny missed a crucial time in Seattle’s establishment during which Maynard was instrumental.

Why Maynard Mattered Most

The broad list of jobs that he undertook out of pure devotion to the city make David Maynard, more than any other early settler, the true founding father of Seattle. He opened the first store. He founded the first hospital. He was the first man of the law and the first blacksmith. These accomplishments show just how eager Doc Maynard was to set the town of Seattle moving on the path to success. In the words of Gerald B. Nelson, the author of Seattle: The Life and Times of an American City, “Most importantly, he was Seattle’s first, most personable, and least selfish public booster” (Nelson, 7).

Indian agent, justice of the peace, physician, druggist, blacksmith, notary public, and merchant. Dr. David Maynard’s ultimate contribution to Seattle was his willingness to help the young city succeed, whatever it took. His actions at a multitude of jobs left a lasting impact on what Seattle is today. At his funeral, a townsperson accurately summed up David Maynard’s legacy:

“Without him, Seattle will not be the same. Without him, Seattle would not have been the same. Indeed, without him, Seattle might not be” (Rochester, 1).