On September 23, 1903, notorious outlaw Bill Miner (1846-1913) and two confederates hold up the eastbound Oregon Railroad & Navigation Company passenger train near Portland, Oregon. It is his first attempt at train robbery and it fails. His associates are captured, but Miner manages to escape into British Columbia, Canada. Miner’s second holdup, near Mission, B.C., in 1904, will be eminently successful. The gang will escape with $1,000 in cash, $6,000 in gold dust, and $300,000 in negotiable bonds and securities. It is reported to be the first successful train robbery in Canadian history. In 1905, Miner will be suspected of robbing a Great Northern Railway passenger train north of Seattle, but he will never be charged with the crime. His last train holdup in the Pacific Northwest will occur in British Columbia in 1906, and will be a fiasco. Miner and his cohorts will be captured, convicted of robbery, and sent to the B.C. Penitentiary at New Westminster. In 1907, Miner will escape and will never again be seen in Canada. In 1911, He will be convicted of train robbery in Georgia and sentenced to 20 years at hard labor. He will die of gastritis at the Georgia State Prison in Milledgeville on September 2, 1913.

Rustling Horses, Holding Up Stagecoaches

Ezra Allen Miner was born in Vevay Township, Ingham County, Michigan, on December 27, 1846, to Joseph Miner (1810-1856) and his wife, Harriet Jane Cole (1816-1901). He had four siblings: Harriet R (b. 1836), Henry C. (1840-1864), Mary Jane (1843-1920) and Joseph Benjamin (1853-1872). In 1860, following the death of Joseph Miner Sr., the family moved to Placer County, California, except for Henry who had enlisted in the Union Army. Miner dropped the name "Ezra" and began using "William" in the early 1860s. Throughout his criminal career he used a multitude of aliases but was always known formally as William Allen Miner.

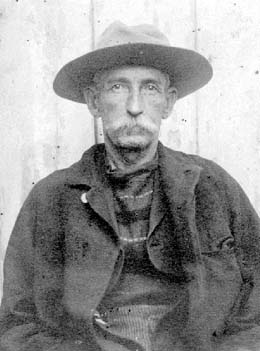

On June 17, 1901, William A. "Bill" Miner, age 54, was released from the San Quentin State Penitentiary in Marin County, California, after serving almost 20 years of a 25-year sentence for stagecoach robbery. A career criminal, he had spent more than 33 years of his life behind bars. Miner didn’t particularly excel at banditry, but he did at being caught and served five terms at San Quentin. He began in 1863 rustling horses and then escalated to stagecoach holdups. Although generally armed, he reportedly never killed anyone and directed most of his criminal activities toward corporations rather than the public. Upon his release from San Quentin after 20 years, Miner discovered that stagecoaches had become obsolete; railroads now carried all the high-value cargo.

Resuming His Criminal Career

After leaving San Quentin, Miner made his way to Washington state ostensibly to visit his two sisters, Harriet and Mary Jane, the last surviving members of his family, and to regain his life. Louis W. Wellman (1840-1915) and his wife, Mary Jane (Miner), had a 160-acre homestead on Hannigan Road, south of Lynden in Whatcom County. Their daughter, Dora (1868-1933), was married to John J. Cryderman (1861-1953), a civil engineer, and he, in partnership with Wellman, owned an oyster bed on Samish Bay near Blanchard in Skagit County. Wellman gave Miner an opportunity to redeem himself and gave him gainful employment picking oysters.

In reality, Miner had gone to Whatcom County to join forces with John E. "Jake" Terry (1853-1907), his former San Quentin cell mate. Terry had been released from the penitentiary on June 2, 1902, and he and Miner rendezvoused in Bellingham. Terry, alias "Cowboy Jake" was a career criminal and had lived in northwest Washington for many years. Most of his activities involved smuggling illegal aliens and opium, but he had also tried counterfeiting, albeit unsuccessfully. Terry took up residence in Sumas on the U.S.-Canadian Border. Locally, he was known as "Terrible Terry" because of his often erratic and violent behavior.

Miner managed to stay out of trouble until the summer of 1903, when he was contacted by Gay Harshman, age 43, another acquaintance from San Quentin State Penitentiary. Harshman, also an habitual criminal, decided to rob a train and enlisted Miner’s assistance. Neither Harshman nor Miner knew the first thing about train holdups, but forged ahead with their plans. While picking oysters, Miner had befriended Charles Hoehn, a 17-year-old who lived in Equality Colony, a socialist community near Edison on Samish Bay, and inveigled the youth into joining the scheme.

Crimes Bungled and Aborted

On Saturday night, September 19, 1903, the bandits intended to rob the Oregon Railroad & Navigation Company (OR&N) passenger train to Chicago. They chose Clarnie, a small town 10 miles east of Portland, for the heist, theorizing that after the robbery they could hide in the big city of Portland. But nothing transpired as planned and the train sped on by the intended site of the robbery.

Undaunted, the trio made a second holdup attempt on Wednesday night, September 23, 1903, this time near Troutdale, 15 miles east of Portland. The gang used several sticks of dynamite to blow the doors off the express car. The messengers inside resisted with deadly force. A short gun battle ensued during which Harshman was hit in the head with a load of buckshot and presumed dead. Realizing the futility of the robbery attempt, Miner and Hoehn fled, leaving Harshman behind. News of the holdup was immediately wired to Portland and a large posse, led by Multnomah County Sheriff William Storey and Captain James Nevins, head of the Pinkerton Detective Agency in Oregon, was dispatched to the scene on a special train. Harshman was found lying in a ditch, unconscious and bleeding profusely from a head wound. He was taken into custody and transported to Good Samaritan Hospital in Portland for medical treatment. Physicians thought Harshman would probably die without regaining consciousness, but he did not.

Meanwhile, Miner and Hoehn crossed the Columbia River to Washington in a rowboat. The pair split up, agreeing to meet in Tacoma before returning to Skagit County. There were no leads to their identities and the bandits avoided capture for a time. Harshman eventually recovered and related the details of the holdup, naming his confederates and where they could likely be found. Captain Nevins ferreted out Hoehn’s location through an informant and on Wednesday, October 7, 1903, had him arrested in Skagit County by Sheriff Charles A. Risbell (1869-1904). Hoehn soon confessed to the attempted robbery and fingered Miner as being involved. Miner learned of these developments from the Bellingham Herald and, fearing his own arrest, fled to Canada with the help of smuggler Jake Terry. He left behind at the Wellman residence Harshman’s overcoat stained with blood. Sheriff Storey, armed with an arrest warrant, went to Bellingham, but he was a day late. Miner had already decamped, but Storey seized the bloody overcoat as evidence of his involvement in the crime

Harshman and Hoehn were removed to Portland, Oregon, for trial. On Friday, November 13, 1903, Harshman, still suffering from his head wound, pleaded guilty to assault with a deadly weapon and the attempted holdup of a passenger train. Hoehn’s case went to trial and he was found guilty of these charges. Multnomah County Superior Court Judge John B. Cleland sentenced Harshman to 12 years and Hoehn to 10 years imprisonment at the Oregon State Penitentiary in Salem. Oregon Governor George E. Chamberlain commuted Hoehn's sentence because of his young age, and he was released from prison on November 14, 1907. Harshman was released on March 28, 1912, after serving more than eight years of his sentence.

Further Crimes Contemplated

Meanwhile, Miner made his way to Princeton, British Columbia, and took up residence at the Schisler farm, using the alias George W. Edwards. He claimed to be a mining engineer who had a gold mine in Argentina. Miner befriended a fellow American named Jack Budd who had a ranch nearby the Schislers. He moved to the Budd ranch in the summer of 1904 and made it his base of operations. In Princeton, Miner met another American named J. William Grell (1869-1927), alias William J. “Shorty” Dunn, and cultivated his friendship.

While living in British Columbia, Miner joined forces with Jake Terry in smuggling undocumented Chinese immigrants and opium across the border into the United States. At one time, Terry had worked as a railroad engineer and he had an understanding of rail operations as well as knowledge of the obscure border crossings in Whatcom County. Together, they hatched a plot to hold up a train in Canada. Miner recruited Dunn, who was pliant by nature, to participate in robbery. After due consideration, Terry and Miner decided to target the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) Transcontinental Express No. 1 at Mission, 40 miles east of Vancouver, where the steam locomotive stopped to take on water.

Robbing the Canadian Pacific Railway

At 9:30 p.m. on Saturday, September 10, 1904, the CPR express train pulled under the water tower at Mission Station. The area was covered by dense ground fog, enabling the three bandits to climb aboard unnoticed. They hid on the platform behind the coal tender until the train left the station and then accosted engineer Nathaniel J. Scott and fireman Harry Freeman at gunpoint. Scott was forced to stop the train at Silverdale crossing, approximately five miles west of Mission, and there uncouple the engine and express car from the passenger cars. The brakeman, William Abbott, escaped from the train and ran back to Mission to report the crime, but the station agent didn't believe his story.

Miner had Scott move the engine and express car a few miles up the tracks and then forced the express messenger, Herbert Mitchell, to open the safe which contained $6,000 in gold dust and $1,000 in cash. Before leaving, Miner collected the pouch of registered mail which contained $50,000 in U.S. government bonds and an estimated $250,000 in negotiable Australian securities. The holdup had taken only 30 minutes. To further delay the train, the bandits threw the fireman’s shovel into the coal hamper feeding the engine.

This was the first successful train robbery in Canadian history.

Upon reaching Vancouver, the train crew told the British Columbia Provincial Police and Canadian Pacific Railway detectives that the robbers had American accents and appeared to be professionals. The police enlisted the assistance of the Pinkerton Detective Agency, which had experience chasing train robbers. Captain James E. Dye, head of the Pinkerton office in Seattle, was eager to help and immediately dispatched several agents to the border. The British Columbia government and Canadian Pacific Railway offered rewards totaling $11,500 for the capture of the bandits. Railroad officials were concerned because the Canadian Pacific was financially responsible for the stolen bonds and securities. The Canadian government was concerned that outlaws, thinking trains were easy prey, might start a crime wave.

The leads all went nowhere and after about a week the official hunt for the train robbers was discontinued. Captain Dye was convinced that Bill Miner was responsible for the heist as he was the only person who fit the gang-leader’s description. Pinkerton detectives were still searching for Miner in connection with the Oregon Railroad & Navigation Co. train robbery committed one year earlier.

Miner convinced his partners that the bonds and securities were too big to fence, easy to trace, and therefore worthless. Aware that they might be useful in the future, however, he carefully hid these assets where no one else could find them. After dividing the gold and cash, the gang split up: Miner returned to the Budd ranch, Dunn to Princeton, and Terry to Sumas to resume smuggling.

It wasn’t long before Miner was considered the prime suspect in the Canadian Pacific Railway robbery at Mission. Terry and Dunn, however, were unknown and remained in the clear. Miner hatched a plot to return the bonds and securities to the CPR without risking capture, using Terry as an intermediary. Mainly he wanted immunity from arrest and prosecution in Canada, but Terry could demand a handsome finders-fee from the railroad which the two crooks would then split. Terry attempted to pursue the scheme to extort the railroad, but the CPR feigned little interest, denying that any bonds or securities had been stolen.

More Train Robberies

On Monday, October 2, 1905, the eastbound Great Northern Railway Flyer was held up at the Raymond brickyard, five miles north of Ballard (now part of Seattle) in King County, Washington. Although the bandits were never apprehended, a British Columbia newspaper named Bill Miner and Jake Terry as the likely culprits.

Terry had been a railroad engineer and was familiar with the Great Northern route through the Puget Sound region. And the modus operandi was very similar to Miner’s. A masked bandit snuck onto the platform in back of the coal tender as the train moved slowly out of Seattle. He then accosted the engineer, John Calder, and the fireman, Edward Goulett, and forced them to stop the train at a place along the tracks marked by a campfire. He was there joined by another masked bandit with an armload of dynamite, which they used to blow open the safe. It was rumored that the holdup men stole as much as $36,000 in gold bullion, but the actual amount is unknown. The Great Northern Railway claimed the loss was approximately $700, not counting the damage to the express car.

Terry was irate when the newspapers named him as a possible suspect in the Great Northern Railway robbery. He claimed he was sick in bed at the Mount Baker Hotel in Bellingham on that day and had no knowledge of Bill Miner’s whereabouts. Great Northern offered a reward of $5,000 for the arrest and conviction of each of the holdup men. Washington State Governor Alfred E. Mead (1861-1913) offered an additional $1,000 reward for the capture of the bandits. But the crime went unsolved.

Miner’s last caper in the Pacific Northwest occurred on Wednesday night, May 9, 1906, near Ducks Station (now Monte Creek), 17 miles east of Kamloops, B.C. He had decided rob the westbound CPR Imperial Limited No. 97, en route to Vancouver. Terry was involved in his own criminal pursuits and unavailable to participate. Miner recruited Shorty Dunn and a transient named Louis Colquhoun for the job. Miner boarded the train unnoticed and took command of the locomotive after it left Ducks. He forced the engineer to uncouple the engine and first car and then pull ahead a few miles and stop. Dunn and Colquhoun, carrying sticks of dynamite, joined Miner and together approached the rail car. The mail clerks weren’t carrying firearms and offered no resistance. Miner soon learned he was robbing the baggage car. The express car, carrying the registered mail and high-value items, had been uncoupled and left behind with the passenger cars at Ducks. Undaunted, Miner quickly searched through the mail and stole $15.50 and a package of liver pills. However, he missed several small parcels said to contain $40,000 in bank notes. Miner had the engineer pull ahead another few miles and then the bandits left the train.

Captured and Tried

Although the heist had been a dismal failure, the Canadian Pacific Railway, in conjunction with the Canadian government and the British Columbia provincial government, immediately posted a reward of $11,500 for the capture of the men, dead or alive. A posse led by B.C. Provincial Police Constable William L. Fernie tracked the bandits south toward Douglas Lake. On Friday, May 11, 1906, a detachment of Royal Canadian Northwest Mounted Police, led by Sergeant J. J. Wilson, was dispatched from Calgary, Alberta, to take part in the manhunt. In the pouring rain, Constable Fernie and his posse continued to follow the trail south and on Monday, May 14, they spotted the three fugitives at a makeshift camp site. He made contact the Mountie detachment and together they surrounded Miner and his cohorts. Miner and Colquhoun surrendered without a fight, but Dunn drew a firearm and attempted to flee. He exchanged several gunshots with the officers and was wounded in the leg. Sergeant Wilson had the prisoners transported to Quilchena, where Dunn’s bullet wound was treated, and then on to the jail at Kamloops. A large crowd stood in the rain to watch as the outlaws were driven into town on a borrowed buckboard.

Miner insisted his name was George W. Edwards, a gold prospector from Princeton. However, his identity had been positively established by a mug shot and detailed description furnished by the Pinkertons. A mail clerk on the train had seen Miner’s face and identified him as the gang leader. After a preliminary hearing on May 17, the prisoners were bound over for trial in British Columbia provincial court.

The first trial of the defendants, held in Kamloops on Monday, May 28, 1906, ended with a hung jury. The second trial was held on Saturday, June 1, and that evening, the jury brought in a unanimous verdict of guilty. The presiding justice, P. A. E. Irving, sentenced Miner to life imprisonment because his lengthy criminal record. Dunn was given a life sentence, primarily for assaulting police officers with a firearm. Colquhoun, who had served two years at the Washington State Penitentiary for petty larceny, was sentenced to 25 years. The following day, a large crowd gathered to watch as the prisoners, manacled and under heavy guard, were put aboard a westbound Canadian Pacific Railway passenger train. The tracks ran conveniently by the British Columbia Penitentiary at New Westminster, their new home.

A Negotiated Escape?

Miner boasted that no prison walls could hold him so he was kept in maximum security for a year. Eventually, the penitentiary staff relaxed their guard, convinced that Miner was too old and feeble (he was 60 years old) to escape, and allowed him visitors. Catherine Bourke, daughter of Deputy Warden C. C. Bourke, attempted to reform the wily convict with religious materials in which he feigned interest. Deputy Warden Bourke, believing Miner had changed his evil ways, granted him permission to work outside in the prison brickyard. On Thursday afternoon, August 8, 1907, Miner and three other inmates managed to tunnel under a board fence, obtain a ladder from the work shed, and scale the 12-foot outer wall of the penitentiary undetected. A tower guard eventually spotted the abandoned tools and wheelbarrows and sounded the alarm. It took a half-hour for the guards round up and complete a head count of the inmates before the pursuit began. They captured three of the escapees in relatively short order, but Miner had quit his associates and could not be found. He was never seen again in Canada.

Within days, the newspapers reported that Miner’s escape from the penitentiary had been too easy and the event became a controversial political issue in Canada. It was common knowledge that Jake Terry had been attempting to negotiate with the Canadian Pacific Railway to return the bonds and securities, stolen in 1904, for certain considerations. However, Canadian Pacific Railway officials believed Terry had been involved in the heist and deemed him untrustworthy. Since Miner was in custody, he was no longer interested in immunity from prosecution and could now possibly arrange a settlement with the railroad himself. Terry attempted to keep his hand in the negotiations, but neither he nor Dunn had any idea where Miner had hidden the booty.

The speculations and accusations went as follows. The Canadian Pacific Railway wielded significant political influence, but couldn’t promise Miner a full pardon and Miner refused to relinquish the bonds and securities without a written guarantee. The solution may have been to secretly contrive a breakout from the prison. But the Inspectors of Penitentiaries Office in Ottawa investigated Miner’s escape and concluded there had been no collusion with prison officials. If there had been negotiations between the railway and the train robber, Miner would have returned the bonds and securities to railway officials once he crossed the border into the United States. The Canadian government, after much discussion in parliament, refused to institute a full inquiry into the incident.

Back in the U.S.A.

After Miner’s departure from Canada, he migrated to the Midwest and supposedly lived an uneventful life. There was speculation he had traveled through the Puget Sound region and retrieved the gold bullion stolen from the Great Northern Railway robbery in 1905 to fund his lavish lifestyle in Denver. After squandering his money, Miner and an acquaintance named Charles Hunter traveled east, working in sawmills and coal mines. While working at a sawmill in Virginia, Miner and Hunter met James Hanford, an itinerant laborer from Nebraska, and together they plotted to rob a train.

At 4:00 a.m. on Saturday, February 18, 1911, the trio held up Southern Railway fast mail train No. 36, en route from New Orleans to New York City, at White Sulfur Springs, Georgia and stole $2,200. They were captured four days later and convicted of train robbery in Gainsville on March 3, 1911. Miner was sentenced to 20 years and Hunter and Hanford, who had pleaded guilty, received 15 years at hard labor. On March 15, Miner, now age 64, and his two confederates were sent to the Newton County Convict Camp at Covington, Georgia, to work on the chain gang.

On July 8, 1911, Miner, pleading poor health, was transferred to the Georgia State Prison Farm at Milledgeville. Three months later, on October 18, Miner and two other inmates escaped from the prison farm. He was captured on November 3 and returned to the Milledgeville prison. Miner, accompanied by two prisoners, made another escape attempt on June 27, 1912, but was captured on July 3 in a swamp near Toomsboro, just 20 miles from the prison farm.

A Bandit's Last Days

During the flight, Miner nearly drowned when a small boat the fugitives had stolen capsized. Miner ingested a large quantity of fetid swamp water and came down with a severe case of gastritis. He battled the affliction for more than a year before succumbing on Tuesday, September 2, 1913. He was buried in an unmarked grave at Memory Hill Cemetery in Milledgeville on September 8, 1913.

In February 1964, local historian James C. Bonner had a headstone placed on Bill Miner’s grave. The engraving reads "Bill Miner -- The Last of the Famous Western Bandits, Born 1843, Died in the Milledgeville State Prison Sept. 2, 1914." The dates of birth and death were wrong, but it was a nice sentiment and underscored Miner’s propensity to lie about his history.

The Partners in Crime

Jake Terry’s association with Bill Miner ended abruptly on Friday, July 5, 1907, when he was killed in Sumas by Gust Lindey, a telegraph lineman, for sleeping with his wife, Anna. The postmortem determined that Terry had been shot twice in the head at close range with a .38 caliber revolver. Hundreds of curious spectators viewed the notorious outlaw’s body as it lay instate at the Albert R. Maulsby Undertaking Parlors in Bellingham. There was no funeral and no one appeared to mourn the death of "Terrible Terry." On Monday, July 8, he was buried in an unmarked grave in potter's field at Bayview Cemetery in Bellingham at public expense. (Whatcom County contract with Maulsby to bury the indigent paid only $7.50. The cemetery received $5 paid for the plot and the sexton $2.50 for his services -- Maulsby received nothing for the cedar-plank casket and his work.) Although initially charged with first-degree murder, the case against Gust Lindey was dismissed on Saturday, October 12, 1907, by Whatcom County Judge Jeremiah Neterer upon motion of Prosecutor Virgil Peringer (1865-1945), when Sheriff Andrew Williams determined that he had acted in self defense.

Louis Colquhoun was in the infirmary at the British Columbia Penitentiary, suffering from tuberculosis, when Miner's controversial escape occurred. He informed authorities he hadn’t seen or spoken with Miner and had no knowledge of his intentions. Colquhoun died of TB in the penitentiary infirmary on Saturday, September 22, 1911.

For being a model prisoner, Shorty Dunn's life sentence was reduced to 15 years and he was paroled on May 25, 1915. He remained law abiding and was eventually granted Canadian citizenship under his true name, J. William Grell. Dunn spent his time prospecting for gold and drowned when his canoe overturned on the Tetsa River in far northern British Columbia in 1927.

Bill Miner’s notorious career as an outlaw became the subject of numerous articles and books. In 1982, Canadian film producer Phillip Borso, doing business as Mercury Pictures Inc., made a major motion picture titled The Grey Fox, starring Richard W. Farnsworth (1920-2000), about Miner’s criminal exploits in the Pacific Northwest. It is considered by critics and the Toronto International Film Festival to be one of the 10 best films ever produced in Canada.