Marie Svoboda, Seattle’s pioneering grande dame of yoga, opened her Queen Anne studio in 1969. It was a bold move for one of the city's few leotard-clad women then offering yoga classes at community centers and YWCAs, careful not to frighten customers away with esoteric chants, or talk of chakras and third eyes. Svoboda’s narrow, loft-like space at 6 ½ Boston Street was the sole studio listed under "yoga" in that year's yellow pages. She taught hatha yoga, an ancient system of postures designed to strengthen, stretch, and ultimately relax the body, mind, and spirit. Charismatic but stern, diminutive but dominating, Svoboda taught in a style resembling that of the ballet mistresses with whom she once trained in Prague, where her married surname translates as freedom. "The only freedom," she often proclaimed in her throaty, heavily accented English, "is through discipline," a novel concept for younger students, steeped in the 60s counterculture. Forty years later, when Svoboda retired, yoga studios had sprung up in damp Seattle neighborhoods like mushrooms, with a fair number of them operated, staffed, and patronized by former students whom she had inspired. Svoboda lived to see yoga grow so popular that a single Seattle yellow page could barely contain all the studio listings. But if each teacher were required to be certified according to Svoboda's exacting standards, few would have survived her scrutiny. In all matters of physical movement, correction -- not approval -- was her raison d'etre.

A Born Dancer

Marie Martina Anna Jana Ruzena Vojtovawas born on December 21, 1920, in Nova Kdyne, a small, remote town in southern Czechoslovakia. Her father, Frantisek Votja, was a legally trained notary who specialized in the handling of trusts and estates; her mother, also named Marie, was a classically schooled soprano. Many years later, Svoboda would write that since Nova Kdyne was without a theater or cinema, she could not possibly have seen a ballerina dancing en pointe when she was 4 years old. Yet according to her mother, that was the age at which she walked on her toes -- not the tips, but the tops. Impressed, her mother soon bought her a tiny pair of ballet slippers.

The Vojta family, which included an older son, Vaclav, moved in 1925 to Melnik, a scenic town where the Moldau River flows into the Elbe. Prague's proximity allowed Marie to take her first ballet classes. Treasured teachers came to include a Madame E. Pechackova and Helena Stepankova, prima ballerina emerita with the National Theatre Ballet, who taught Russian technique. After coming under the tutelage of Joe Jencik, a National Theatre artistic director, Svoboda performed in his modern dance concert group. She also danced with the National Theatre's ballet company, the Olomouc City Opera, and Prague's Modern Opera Studio, with energy to spare for downhill skiing, another passion of hers.

It is not clear how Svoboda's dance career was affected by the brutal six-year Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia that began in 1939; she seldom spoke of her past even among her circle of intimates in Seattle, students whom she befriended or mentored. Her brief unpublished autobiographical essay does not mention the 1944 death of her father, whom she adored, nor the difficulties endured by artists of every sort as a result of German animosity toward the Czech cultural elite. Neither does she point to the 1939 closing of all Czech universities, which included the execution and incarceration of numerous student leaders, as the reason why her studies in physical education had to be abandoned. But such turmoil is suggested in her report of two mentors' fates: Madame E. Pechackova died due to occupation-era hard labor in uranium mines, and Jencik had a fatal heart attack during the Prague uprising of 1945 soon after his release from a concentration camp. On a prouder note, Svoboda emphasized that the road used by General George Patton to invade and help liberate Czechoslovakia lay near her birthplace.

Post-War Years

After V-E Day, Svoboda returned to Prague's Charles University, where the medical school classes taken by physical education majors included anatomy, physiology, and kinesiology. "All (of) that interested me greatly," she wrote, "and was a great help in my search for correct movement." Svoboda was also influenced by private studies with an instructor in the Mensendieck Method, a corrective and therapeutic exercise technique developed by Dr. Bess M. Mensendieck (1861-1957).

Mensendieck-trained teachers commonly required that students work if not in the nude, then nearly so, to allow for optimal bodily evaluation and adjustments. American-born but Zurich-trained, Mensendieck contended that poor habitual postures, along with inefficient movement, caused physical ailments. She supported her theories in a 1906 book that was targeted toward women and illustrated with instructive photographs of nude female models. Prudish American Comstock laws prevented Mensendieck from being published until 1931, and even then, her models' photographs were painted over with bras and panties.

The Mensendieck Method was widely practiced in Europe, and it provided Svoboda with a firm foundation for the analytical gaze she would later level on yoga students -- to their benefit, if not always their delight. "Marie commented much too frankly on people's bodies," remembers Valerie Easton, a Seattle Times gardening columnist and author whose swayback Svoboda noted in each and every class. "But her pushing caused me to change my body. She made me understand that a hyper-mobile lower back isn't an advantage, it's a recipe for problems. She's why I've been able to garden vigorously and exhaustively without injury for all these years" (Easton email).

Svoboda left Czechoslovakia in 1947 for Washington, D.C. There she married her fiancée, Ladislav Maurice Svoboda (1902-1993), a Czech banker who had just begun a two-year stint as a delegate from the National Bank of Czechoslovakia to the newly formed World Bank.

After the communist coup d'etat in Czechoslovakia, which occurred in 1948 -- the same year that Svoboda gave birth to daughter Jana -- Ladislav applied for permanent residency under the Displaced Persons Act. That request was denied the Svobodas because Ladislav, who remained with the World Bank as a financial analyst, already held a work visa with the rights and immunities of an international organization. The situation remained fraught, however. If for any reason he lost his job, he and his family would have been deported to Czechoslovakia, where he would be in certain danger of prosecution because of his anti-communist feelings and defiance of government orders that he return. Finally, a 1951 immigration visa application was approved, providing a path to U.S. citizenship. "It must have been a terrifying time for them," their daughter Jana Bertkau says. "I remember the tension whenever they talked about Czechoslovakia. Their families (in Czechoslovakia ) were under pressure because of their emigration, and family letters were censored" (Bertkau interview, immigration application).

Among Bertkau's earliest memories of her mother is a vision of her "racing off to teach an exercise class at the Y. 'Slim Down With Marie,' I believe it was called" (Bertkau interview). Later, in exchange for tuition, Svoboda taught P.E. at the private school where Jana attended first grade. Given that Svoboda's husband often traveled to work three-month stints abroad, and that by then she had a second young daughter, Patricia, her independent pursuits and insistence upon living in the city rather than the suburbs were survival skills.

Becoming A Yogini

It was in the mid-fifties that Svoboda had her first formal exposure to yoga, in D.C. classes taught by Indra Devi (1899-2002), then known for giving lessons to movie stars at her L.A. studio and called "the mother of Western yoga." Devi -- nee Eugenie Peterson -- was not only a daughter of Russian nobility, but in the world of modern yoga, she was also of royal lineage: the first female protegé of legendary guru Sri Tirumalai Krishnamacharya (1888-1989). Apart from Devi, Krishnamacharya's most influential students included two of the most significant "fathers" of Western yoga; B. K. S. Iyengar (b. 1918), who emphasized posture precision, and Pattabhi Jois (1915-2009), creator of vigorous ashtanga yoga sequences. Devi's outstanding quality, by contrast, was gentleness.

"Don't sit there like a plum" is a "Marie-ism" that Svoboda would employ to prod her own students, but plum-like was the pedagogical position assumed by Devi, swathed in her sari, when Svoboda encountered her. Devi left the heavy lifting of yogic asanas, or postures, to Bala Krishna, a masterful demonstrator with whom Svoboda would pursue further studies. Nevertheless, Devi appreciated Svoboda's flexibility and athleticism, recommending that she become a yoga teacher herself. Which she soon did, instructing her earliest students in the basement studio of her Cleveland Park home. "At Charles University," Svoboda wrote, "I was exposed to many systems in physical education, but none of them can compare to the oldest system in the world -- yoga ... . It is awakening. It gives one mastery of life" (Svoboda essay).

Svoboda also continued to study dance while in D.C., taking classes from Ethel Butler (1914-1996), a former Martha Graham dancer and a charismatic teacher in her own right. From master to disciple to student -- a standard progression in dance as well as yoga. Learning the Graham technique, invented by an American icon, was a visceral, physical way for Svoboda to absorb her new culture. But in Graham's movement vocabulary, with its emphasis on muscular contraction and release, Svoboda also saw a resemblance to yoga. From then on, she mined every new theory and method of movement or body work that she explored -- and there would be many, from Feldenkrais to Rolf, from Iyengar to Jane Fonda videos and the Bikram hot yoga class she once took -- for ways in which they might complement her teaching.

Yoga classes weren't the only ones conducted in Svoboda's basement studio. She taught her children and others both ballet and Czech national dancing there, and loaned the space for ballroom instruction, too. "There were always streams of people coming to the basement," according to Bertkau. Though Svoboda had no pronounced passion for domestic arts -- the home (upstairs, at least) was a poor container for her abundant energy -- she further bonded with her daughters by driving them off to ski slopes and lecturing, as Bertkau recalls, "that girls are just as good, if not better, than boys, and don't you ever think otherwise" (Bertkau interview). Despite strong pro-American sentiments, born of U.S. aid to Czechoslovakia both during World War II and before Communist rule, Svoboda was horrified by the idea that a daughter of hers might become a cheerleader.

In 1960, the year when Svoboda and her husband became naturalized U.S. citizens, they also left the country, taking their family to Karachi, Pakistan, for Ladislav's two-year World Bank mission. Though Svoboda did not record training with one special Indian guru while based in Pakistan, she did find teachers who deepened her knowledge of asana as well as yoga's philosophical underpinnings -- perhaps even discovering that in Sanskrit, the language of yogic chanting, "svoboda" means "knowledge of one's self." She also took classes with her daughters in Indian dance, which she learned has its roots in yoga, and performed with the Ghanisham dance troupe. Two more foreign postings would take the Svobodas to Kuwait, where Svoboda is thought to have taught yoga at the American embassy, and then to Malaysia, where she studied tai chi chuan.

"All the countries were interesting in their own way," she wrote, "but somehow the diverse Malaysian society was my favorite. There were Malays, Chinese, and (East) Indians" (Svoboda essay). Since the Indian community, as she noted, often invited lecturers from their homeland, it's possible that Svoboda attended those that fed her interest in yoga.

While the family was living in Kuwait, Czechoslovakia's borders opened so that Svoboda and her husband could return for the first time since 1947, taking their daughters to visit relatives the girls had never before met.

Re-introducing Yoga to Seattle

In 1965, while Svoboda was still in Malaysia, her eldest daughter enrolled as a freshman at the University of Washington -- chosen by Svoboda because her brother, who had crossed the German border of Czechoslovakia in the early 1950s, now lived in the area and she wanted Jana to have family nearby. After leaving Malaysia, Svoboda also moved to Seattle, with her younger daughter, Patricia. "I think Mom decided I needed more supervision," Bertkau says. "I guess I must have been writing some pretty racy letters home" (Bertkau interview). Svoboda's separation from her husband was temporary at first but became legal in 1969, with the couple sustaining friendly communications.

Soon after Svoboda's 1966 arrival in Seattle, she arranged to teach yoga at the YWCA and other venues -- the University Unitarian Church, The Lake City Community Center, Queen Anne High School, the Aqua Barn Ranch in Renton. In 1967, a three page photo-spread featuring her Y class for women appeared in The Seattle Times magazine, with Svoboda quoted in the text: "Yoga is a way of life. There is no age limit for students. It is a discipline involving gentle exercises. If you want to look younger, reduce your waistline, improve your mental and physical outlook, be good to yourself, try yoga" (The Seattle Times, April 2, 1967).

An effective, if pasteurized, pitch. Eight weeks later, Svoboda appeared on a local afternoon TV show, demonstrating poses. From the start, her approach was more prudent than that of the last yoga teacher to make a splash in Seattle. In fact, Pierre Bernard (1876-1955), a groundbreaking American yoga master whose four "tantric lodges" for the study of hatha and raja (spiritual) yoga were established between 1906 and 1909, was so controversial that he helped give yoga a questionable enough reputation to linger in the city for generations, fueling what Bernard's biographer termed "an American war against yoga, a decades-long conflict waged by the media, clergy, and even the government" (Love, 5).

The prominent followers whom Bernard recruited while in Seattle included Judge John Stanley Webster (1877-1962), who would later become a Republican congressman. But Bernard had his eye on New York, and was living there when he became the center of a juicy 1910 scandal -- charged, but never convicted, with having "inveigled and enticed" a female Seattle student into accompanying him across country and having a sexual relationship with him. The Seattle Times carried the news about Bernard in a sensational May 6 front page story that recounted his local "escapades." One former student who was anonymously quoted said that "this human viper" offered seven different expensive degrees guaranteed to provide nothing less than "mastery of the universe."

Svoboda may never have heard of Bernard, who eventually re-established an influential New York yoga organization with the support of students who were celebrities and socialites; his biography wasn't published until 2010. But unlike Bernard, she instinctively soft-pedaled anything smacking of the occult, developing her appeal to the widest possible audience and keeping her focus on the health benefits of hatha yoga. Even so, she might well have been irked by the first newspaper article in which she was featured after her studio opened.

"Yoga Buffs Find Relaxation After Tension, Drug Highs" read the peculiar headline. An accompanying photograph sounds another discordant note, with Svoboda sitting by while an advanced student poses with legs wrapped around her head; not the best illustration of Svoboda's contention that "yoga is not a contortion, but it is an ideal physical system." Another photograph shows a blissed-out Hare Krishna slumped over his harmonium, included, no doubt, because the Hare Krishna Temple was then the sole companion of Svoboda's studio under the yellow pages "Yoga" listing. A Hare Krishna's yoga practice simply requires chanting all the names of God, and if this fellow had appeared in a class of Svoboda's, she would have found much to correct. Take off that robe, I can't see what your body is doing. Focus your gaze. Sit up straight. Still, Svoboda spoke to the article's premise by stating that drugs were not necessary to elevate the mind -- "oxygen can do it with concentrated exercise" -- and backed up that appeal to youth by offering half-price classes in the University District (The Seattle Times, August 23, 1969).

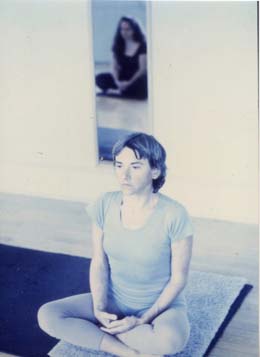

"Yoga is in," a 1970 Seattle Post-Intelligencer article proclaimed, "it's hip" (Seattle Post-Intelligencer, February 8, 1970). While it was true that yoga authorities were just then beginning to show up in the popular culture with instructional TV series and bestselling books, a live teacher is essential to real progress. For the serious would-be student in Seattle, Svoboda was the only game in town. In a photograph accompanying the P-I piece, she proved to be her own best advertisement -- a lithe 50-year-old woman (though her age was not given) in King Dancer's Pose, an elegant but difficult standing posture in which the body is arched with shoulders fully rotated to draw one foot toward the back of the head.

Meanwhile, Svoboda immersed herself in the city's cultural life, attending dance and musical events, as well as its natural surroundings. "I love beautiful Seattle very much," she wrote. "I cannot see enough of the gorgeous mountains -- in winter while skiing and in summer while hiking" (Svoboda essay).

Building a Legacy

One of Svoboda's earliest Seattle protégés was Bob Smith, who began studying with her in 1971 when he was 22 years old, a self-described hippie drop-out. During his second class, "she gave me the eye and said, 'You've done this before. It's nice to see you.' I'm not sure exactly what she meant, but it was a magical moment, and I was hooked for good. Underneath her powerful persona, Marie had the warmest heart imaginable. I won her over because I practiced what she taught, possibly like no other student of hers ever had" (Smith interview). Smith, who would go on to open his own studio and dedicate the yoga book he authored to Svoboda, came to feel like an adopted son. During his four years with her, Svoboda routinely hosted other teachers in workshops she organized and after each one, she would take Smith aside to dissect what was wrong about that teacher's approach and what was right; then they would spend hours working in the studio, experimenting with new concepts.

Svoboda, still an avid skier, took a bad fall while racing on Snoqualmie Mountain and fractured her pelvis. That night, as Smith recalls, Svoboda's daughter, Patricia, then a University of Washington student and an accomplished pupil of her mother's, taught class. Everyone expected that Svoboda would be out of commission for weeks, if not months, to come. But the next night, she conducted class from a chair, moving only her head and eyes. "She persevered through the pain," Smith says, "and within a week, she was able to do a few postures. Within two more weeks, she was doing the majority of postures. I asked how she could possibly heal in such a short time, and she said that she spent every waking hour meditating upon it. From that moment on I believed she had the power that any great yogi, sufi, or rishi has. I still believe this today."Like others close to Svoboda, Smith appreciated her dark sense of humor. "Most of Marie's students were too intimidated by her to laugh, but I thought she was hilarious" (Smith interview).

"This is how they kill chickens," Svoboda might say in her Marlene Dietrich-ish deadpan as she adjusted a student's neck (Blanchard interview). "What do you do for a living?" she once asked a new male student, and then, after being told: "Well, you'd be a better vice-president if you fixed those arches" ("Marie-isms"). One sweat-covered beginner was informed at the end of class that "you got your ten dollars' worth" ("Marie-isms"). A common diagnosis of hers was, "you're strong in all the wrong places" ("Marie-isms"). Novelist Stephanie Kallos remembers being too amazed to laugh when Svoboda, whose youthful vigor and ramrod spine made her age hard to guess, did a demonstration in which she gradually slumped, crabbed and contracted her body "until right before our eyes, she turned herself into a little old woman" (Kallos interview). In an instructional video that Svoboda made while in her seventies, she introduces her effortless-looking headstand with a world-weary voice: "Everyone wants to do always the headstand" (Svoboda video).

Svoboda trained the full force of her analytic powers and strict teaching style on newcomers, who didn't always return for more. She was not a teacher who would, at the end of class, massage your temples with scented oil while you lay in shavasana (the traditional rest at the end of a session of yoga). Still, many of those who studied with her speak of the care with which she would focus on the least able student present, then create sequences to address that person's issue or injury. By session's end, she'd conducted an anatomy lesson that was instructive for everyone.

San Francisco yoga teacher John Marino came to Svoboda's class as a rank beginner in 1974, nearly immobilized by rheumatoid arthritis. "My shoulders were collapsed into my body," he says. "My hands and feet were crooked from the ravages of the disease. A lot of yoga experts would have taken one look and said, 'You're not appropriate for this class.' But Marie just gazed at me with such compassion and proceeded to teach an entire class focused on restoring rotation in my joints so my torso could remain erect." Though Marino soon moved to California, "I continually practiced the things Marie taught me until I reversed enough damage to begin studying yoga in earnest. I put Marie up there with Iyengar, Jois, and all the other masters" (Marino interview).

Svoboda was too much a synthesizer to be confined by Iyengar's technique, but she was in agreement with his philosophy that enlightenment flows from awakening all the body's cells. In 1980, she joined a group of Seattle yoga teachers and enthusiasts to attend a three-week course with Iyengar at his compound in Poona, India, practicing yoga for five hours each day. Among the group was Nancy Easterberg, who had turned to yoga to counteract the effects of childhood polio that left her with an atrophied leg and one foot two sizes smaller than the other. The medical opinion, which Easterberg refused to accept, was that she would be in a wheelchair by the time she was 60. Impressed by Svoboda, Easterberg began rigorous study with her in 1984, taking an average of six classes a week for 14 years, until Svoboda closed her Boston Street studio. "I'm 70 now," Easterberg says, "and Marie is the reason that I'm on my feet today, that I'm still walking" (Easterberg interview).

Kathleen Hunt came to Svoboda as a hyper-flexible dancer who needed to work on strength to prevent further injuries. She studied with Svoboda for 10 years, eventually opening her own Seattle studio. She still uses Svoboda's methods for strengthening the feet -- "they're your foundation," she says, quoting Svoboda -- as well as the alignment corrections and wall work that were unique to her (Hunt interview).

Like Bob Smith, Hunt operates a yoga teacher-training program out of her studio. Svoboda preferred to train only a few students into teaching proficiency, but those whom she did would take over the classes she taught -- roughly 15 per week -- during her frequent travels. Svoboda's last protégé, Kelly Blanchard, went into training with her after five years of study. "I try to emulate her amazing creativity as a teacher," he says. "The way that she constructed sequences of small, accurate movements to get you to places where you didn't think you could go was an art form" (Blanchard interview).

Preparation for the Last Breath

Svoboda closed her studio on February 28, 1998, after a new landlord raised the rent. Another studio, Yogalife, eventually took up residence in her old space, and one of the staff instructors, Fran Gallo, was shaped by Svoboda's classes there. "Marie did not give compliments," Gallo says, "yet you loved her as a great teacher. Bob Smith once told me that when he took her class, suddenly everything made sense. I think that was true for all of us who went to her searching for a deeper meaning to everyday life" (Gallo interview).

Svoboda continued to conduct classes in private settings for a select circle of students through 2009. She also became a student again herself, taking Pilates at a Ballard gym. During this period, while in her 80s, she had cataract surgery and asked the ophthalmologist when she could resume her headstand practice. "Never," the doctor told her, "it's too dangerous." With that, Svoboda drew herself up to enumerate all the health benefits of performing headstands and then, after failing to convince the doctor, advised him to take up dancing because his body was far too tense and rigid. He would not have been wrong to suspect that she meant his mind as well, since for Svoboda, the two were inextricably linked (Bertkau interview).

In April 2011, after being diagnosed with dementia, Svoboda moved from her Queen Anne condo into a memory-care community in north Seattle. Blanchard offered yoga classes to Svoboda and her fellow residents, carrying forward Svoboda's philosophy of teaching to the conditions in which you find your students. "I taught thirty people," he says, "half of them in chairs and some of them asleep, but I found things that they could do. One day I saw Marie in the hall and said, 'Time for yoga.' She told me with that accent of hers, 'Forget about it.' Marie used to always remind us that yoga is preparation for the last breath, and in the end, she had a kind of sublime peaceful vibe about her" (Blanchard interview).

As a number of former students reverently reported in yogic language on their blogs and Facebook pages, "Guruji Marie transcended her body on December 16, 2012," less than a week before what would have been her 92nd birthday. A March memorial service was planned in Seattle, where Svoboda instructed many hundreds of pupils, but she had requested that her ashes be buried in the country where her life began, in a family crypt.