The city of Union Gap lies in south-central Washington in Yakima County, abutting the southern boundary of the city of Yakima. In 1865 a wagon train on its way to Puget Sound stopped by the Yakima River near where Ahtanum Ridge and Rattlesnake Ridge are separated by a small valley called Union Gap. There the settlers, led by Dr. L. H. Goodwin, decided to stay. In 1869 or 1870 what was then only a small village was given the name "Yakima City." The community developed into a small town and was formally incorporated under territorial law in 1883. In 1884, the Northern Pacific Railway Company unexpectedly decided to place its first and primary Yakima Valley terminal about four miles from Yakima City. As went the railroad, so went most of the town; at least 100 buildings were put on rollers and dragged by horses to the new site, called at first North Yakima and later simply Yakima. What was left of Yakima City was renamed Union Gap in 1917. Union Gap slowly repopulated as Yakima grew to become a regional center of commerce and transportation. By 2013 Union Gap was a city of more than 6,000 people, nearly half Hispanic, serving as a primary retail center for the Yakima Valley.

Indians, Explorers, and Priests

The Lewis and Clark party was greeted with friendliness by Native peoples when it arrived at the confluence of the Yakima River with the mighty Columbia in the fall of 1805. The ancestors of those the expedition encountered had lived in the Yakima Valley for millennia, ranging from the headwaters of the Yakima River in the Cascade Range to its union with the Columbia River in the south, from the mountains into the great, flat stretches of the valley. They were hunters, gatherers, fishers, and traders, and they were known collectively as the Peoples of the Plateau.

The Yakamas were one of many tribes that formed a great but decentralized Indian nation east of the Cascade Mountains. The tribe was a consolidation of several bands and groups that spoke Shahaptan, including the Pish-wana-pum, the Skwa-nana, and, in the vicinity of what would become the town of Yakima City (later Union Gap), the Pah-quy-ti-koot-lema.

It is very likely that the people living along the path of the Yakima River were exposed to non-Indians even before Lewis and Clark's arrival, but most early intruders stayed close to the primary water routes of the Snake and Columbia rivers to the east and south. After the Voyage of Discovery had continued on, other travelers, notably trappers, prospectors, and traders, made their way into the land of the Yakama. The famed Hudson's Bay Company had its men working the area as early as 1812; they would continue as a sporadic presence, but for decades to come sightings of non-Natives in the Yakima Valley would be few and fleeting.

As was true many places in the Northwest, the first semi-permanent non-Indian presence in the Yakima Valley was the Roman Catholic Church. Although the available histories are not in agreement, it appears that Oblate Catholic missionaries Eugene Casimir Chirouse (1821-1892) and Charles Marie Pandosy (1824-1891) first arrived in the area in 1848. Some sources credit them with establishing a mission there, while others claim that in 1851 it was Father Louis-Joseph d’Herbomez (1822-1890), dispatched from Olympia to preach and proselytize in the valley, who founded the mission of St. Joseph d’Ahtanum, just a few miles east of present-day Union Gap.

The U.S. military made an early incursion in 1853 when General George B. McClellan (1826-1885) traveled up much of the length of the Yakima River on a mapping expedition. In 1856, the military established Fort Simcoe about 25 miles southwest of what would become Yakima. The fort was a component of the federal government's efforts to pacify the local Indians and change their way of life forever.

From all accounts, the Indians inhabiting the area were not aggressive in their early dealings with non-Natives arriving from a world they barely knew existed. That would change when authorities decided to remove the tribes from much of their ancestral land so it could be doled out to the ever-growing stream of settlers pouring west. Even tribes that had maintained good relations with settlers now faced terrible choices, and one choice was to fight.

Kamiakin, Isaac Stevens, and the Indian Wars

With the coming of settlers and the imposition of treaties, what had been separate bands bound by blood and language were forcibly consolidated into somewhat arbitrary groups, and those who now live on the huge Yakama Reservation (which takes up more than 62 percent of all the land in Yakima County) are the descendants of many once-independent bands and tribes. Isaac Ingalls Stevens (1818-1862), Washington Territory's first governor and Superintendent of Indian Affairs, was to be the primary instrument of the government's drive to sequester the tribes in the Northwest. His personal feelings about the indigenous population seemed ambivalent and not devoid of kindness and respect at times, but his mandate left little room for sentimentality or the accommodation of Native preferences. Stevens thus set about, with guile and a degree of ruthlessness, to usurp the Indians' traditional lands and move them to reservations that were, almost without exception, either inadequate in size or inappropriate in nature.

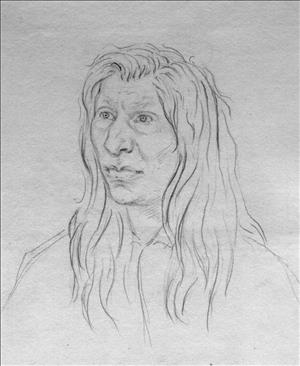

A powerful, wealthy, and charismatic chief of the Yakamas, Kamiakin (ca. 1800-1877), would represent his tribe in the "negotiation" of the Walla Walla Treaty in 1855. In 1841, army explorer Lieutenant Robert E. Johnson had written that Kamiakin was "one of the most handsome and perfectly formed Indians they had met with," but "gruff and surly," and unwilling to sell Johnson's party any horses (Kershner, "Chief Kamiakin").

As chief, Kamiakin (sometimes written "Ka-mi-akin" or "Kamiakun") proved himself in many ways. A half-mile long trench that he dug from a spring to his garden plots east of present-day Union Gap is credited as the first artificial irrigation system in the Yakima Valley. Early pioneers called it "Kamiakin's Ditch," and it may have been this that made them realize that what appeared to be arid, bunchgrass-dominated land needed only water to become fertile and highly productive. Today, what is called "Kamiakin's Garden," located on private land just east of Union Gap, is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Kamiakin, and other chiefs, agreed to meet Stevens at Walla Walla in May 1855. He had been forewarned, notably and sympathetically by Father Pandosy, of the futility of trying to preserve ancestral lands from white encroachment. Before the Stevens meeting, Kamiakin met with other Native leaders at the Grande Ronde River and formulated a plan to draw out their respective ancestral lands on a map, then refuse to cede any of it, to Stevens or to anyone. The settlers could go anywhere else they wanted, but the Peoples of the Plateau resolved to set the boundaries of their own reservations.

Of course, it was not to be. When the Walla Walla Treaty Council met in May near Mill Creek, Kamiakin's coalition fell rapidly apart. Other powerful bands and tribes, notably the Nez Perce, decided to go their own way. Stevens did not have to divide to conquer; long-standing rivalries, jealousies, and distrust prevented Native cohesion, and Stevens bargained, if such it can be called, with a disunited and dispirited group.

The treaty talks dragged on into June. Kamiakin remained adamant and was regarded as a key holdout. Stevens tried both flattery and bribery, to no avail. He then may have turned to threats; according to one source, Kamiakin relented only when Stevens, brandishing his version of a treaty, warned that if Kamiakin and the other chiefs didn't sign, "you will walk in blood knee deep" (Kershner, "Chief Kamiakin"). As one observer later recalled:

"All the chiefs signed, Kamiakin was the last and as he turned to take his seat, the priest (Chirouse) ... whispered, look at Kamiakin, we will all get killed. He was in such a rage that he bit his lips until they bled profusely" (Kershner, "Chief Kamiakin").

Shortly after the signing of the Walla Walla treaty and similar one-sided pacts, the Indian Wars broke out in the Northwest. Kamiakin fought in the first two battles of the Yakama Indian War, at Toppenish Creek (October 5, 1855) and Union Gap (November 9, 1855). Unlike many tribal leaders and war chiefs, he was never captured or broken. At least one historian, A. J. Splawn (1845?-1917), who knew Kamiakin well, believed that the Yakama chief was determined to personally slay Isaac Stevens in the belief that the end of Stevens would mean the end of war and the return of Indian lands. But Stevens was lucky, then, and Kamiakin was unable to carry out his plans. Stevens's luck would run out, though; he died in 1862 while leading Union troops during the Civil War's Battle of Chantilly.

In 1858, when in his late 50s, Kamiakin also fought in the last two major engagements of the Indian Wars, the Battle of Four Lakes (September 1, 1858) and its sequel, the decisive Battle of Spokane Plains (September 5, 1858), an Indian defeat that finally brought the war to a complete end after three years of sporadic fighting. Kamiakin became an exile, moving from camp to camp with an ever-smaller band of followers, his health in slow decline, his power and influence largely spent, and his once-great wealth dissipated. His life ended far from home, at Rock Lake in the Palouse scablands, where he died in April 1887, one day after being baptized into the Catholic faith and given the Christian name "Matthew." He was to suffer one last indignity: The following year a relic hunter dug up Kamiakin's body and stole his head. The rest of his remains were moved and reinterred; the head was never found.

Yakima City

With most Indians moved to reservations, thousands of acres of land were opened to new settlement in Central Washington. The first permanent non-Native settler in the Yakima Valley was Fielding Mortimer Thorp (1822-1893), who in October 1860 came to the Moxee Valley a few miles east of what would become Union Gap. Thorp was primarily a cattleman, and he brought with him a substantial herd that he had raised at his previous homestead in the Kittitas Valley. A severe winter in 1861-1862 nearly destroyed his cattle, but Thorp saved many, stayed put, and prospered. He, his wife Margaret, and their four sons and five daughters would be practically the only non-Native presence in the Yakima Valley for several years, and both the town of Thorp and Thorp Mountain bear the family's name. Families that homesteaded in the valley in the early 1860s after the Thorps included the Saxons, Splawns, and Hensons, none of whom settled right at Union Gap.

The Washington Territorial Legislature established Yakima County on January 21, 1865, after disestablishing the short-lived Ferguson County, which had comprised much of the same area for two years. The new county was bounded by the Simcoe Mountains on the south, the Cascade Mountains on the west, the Wenatchee River on the north, and the Columbia River from below Wallula to Wenatchee on the east. Whether due to the creation of the county or not, immigration into the Yakima Valley started to increase.

Later in 1865 a wagon train traveling to Puget Sound diverted off the main west-bound trail and traveled north up the Yakima River from its confluence with the Columbia. Reaching a space between two hills, called Union Gap, the settlers, led by Dr. L. H. Goodwin, decided to go no farther. Others in the party were Goodwin's wife and children, his nephew Thomas, the Walter Lindsey family, the John Rozelle family, and William Harrington, Rozelle's son-in-law. Goodwin's wife Priscilla (1822?-1865) soon died, on December 18, 1865, and was buried on a nearby cliff overlooking the Yakima River. Her husband (who years later moved to Walla Walla) later donated this land to Yakima City and it became the site of the Pioneer Cemetery, which exists to this day.

Dr. Goodwin established what he called the Spring Creek Homestead, and other immigrants slowly trickled in. In 1869, early arrival Sumner Barker (1814-1879) opened the first store in what would become Yakima City, and in 1870 George Goodwin, one of the doctor's three sons, opened another.

Although now just a small cluster of makeshift houses, it was the first civilian settlement in Yakima County, and under the evanescent name "Mount Ottawa," it was selected by voters as the county seat in 1870. The 89 votes cast in its favor indicated the sparseness of the area's population. The runner-up, with 20 votes, was identified only as "Flint's Store."

In 1872 George Goodwin formally platted and recorded a part of his homestead allotment, using the name "Yakima City." Other families were scattered around the valley, but not in groups of sufficient size to form cognizable communities. Martha Goodwin Beck (1830-1908), sister to Dr. Goodwin and wife of the county's first elected justice of the peace, John Wilson Beck (1828-1903), began teaching valley children as early as 1870. In that same year, brothers Charles and Joseph Schanno moved to the valley from The Dalles, Oregon, and opened a third, larger store at Yakima City. The Schannos claimed homestead on acres of arid, sagebrush-strewn land, and it was there that the small community of Yakima City began to grow. Soon the Yakima County Territorial Court would hold its first sessions there, with Judge J. R. Lewis presiding.

Watering the Land

Most of the Yakima Valley was still deemed too arid for agriculture, except near the banks of rivers and streams. Members of the Goodwin party dug a small irrigation canal as early as 1866, but it was not until 1872 (some sources say 1870) that the Schanno brothers dug a larger ditch from Ahtanum Creek to Yakima City. In that same year, John Beck dug a canal from the Yakima River to his land and started growing fruit trees, with unexpected success.

Two years later the Schanno brothers dug a much larger canal, 18 feet wide and 18 inches deep, which ran nine miles from the Naches River in the north to their homestead at Yakima City. At first the water was used mostly for vegetable gardens and growing a little wheat, but eventually it was realized that much larger tracts of land could be irrigated to grow what would be for a time the county's leading cash crop, alfalfa. The Schannos also began to grow wine grapes, the first in the valley to do so. Other enterprising folks dug additional canals and ditches that soon spider-webbed the western portion of the valley floor, and the full promise of its rich agricultural potential started to be realized.

Despite this progress, growth was slow. By 1875, the year that mail service first came to Yakima County and 15 years after Fielding Mortimer Thorp settled in the Moxee Valley, the population of the entire county was counted as barely 2,000 souls.

Waiting for the Train to Elsewhere

Although its rate of growth was glacial, the little community of Yakima City, being the first in the entire valley, soon declared itself "the Giant of the West," in the apparent hope that it would become a self-fulfilling prophecy. It would not, but the town did progress. As described by a noted Washington historian, by the end of the 1870s:

"[Yakima City] had a Catholic, a Christian and a Congregationalist church, a Methodist society which held services more or less regularly, several shops and mercantile establishments, and presented a thriving appearance to the immigrants as they passed through it on their way to the Sound" (Snowden).

This apparently was not enough; most new settlers had their hopes set on points west and kept going. But the Northern Pacific Railway was coming soon, and the residents of the struggling little town just knew that with it would come access, success, and good fortune. The railroad branch would start at Pasco Junction in the south, run up the valley of the Yakima River, and, it was thought, stop at Yakima City, still the county seat and the largest town in the vicinity. In anticipation of becoming a key stop on the rail line, the town formally incorporated on December 1, 1883. Its few citizens then waited patiently for the crews laying track to come into view on the horizon.

The first train reached Yakima City on December 24, 1884, and at first the Northern Pacific carried freight and passengers to and from the town and kept a station agent there to manage things. It was not to last; on February 4, 1885, the railroad filed a plat for a spot in the middle of nothing a few miles past Yakima City. It was first called "New Yakima," then "North Yakima." To here the Northern Pacific would extend its tracks, and here it would build a depot and a town. As for Yakima City, the train simply stopped stopping there.

There are two or three different stories about why the Northern Pacific Railway decided to give Yakima City what nearly became a death sentence. Officially, the line claimed that the land around the community would become too swampy for railroad use once full irrigation was in place. Other accounts say that Yakima City was insufficiently generous in granting concessions to the railroad in return for putting a depot at the town. A third view was that the railroad simply wanted to build a new town, one that it could control from the start. Whatever the reason, Yakima City did not take this snub passively. Its residents prevailed on the territorial government to file suit against the railroad, a suit eventually heard by the highest court in the land. Meanwhile, the railroad aggressively developed North Yakima, offering free lots to anyone relocating from Yakima City, building a municipal water system, and drawing up a town plan that was, reportedly, "laid out on the general plan of Baden Baden," a spa town in Germany (Lyman, 401).

The case of Northern Pacific R. Co. v. Washington Territory ex rel. Dustin took seven years to get to the U.S. Supreme Court, and by that time the facts on the ground had changed beyond all recognition. The Court's opinion gives a succinct accounting of what the loss of the railroad had done to Yakima City:

"The defendant [Northern Pacific Railway] at one time stopped its trains at Yakima City, but never built a station there, and, after completing its road four miles further, to North Yakima, established a freight and passenger station at North Yakima, which was a town laid out by the defendant on its own unimproved land, and thereupon ceased to stop its trains at Yakima City. In consequence ... Yakima City, which ... was the most important town, in population and business, in the county, rapidly dwindled, and most of its inhabitants removed to North Yakima, which at the time of the verdict had become the largest and most important town in the county" (42 U.S. 492, 507).

Adding insult to injury, the Court also pointed out:

"The record showed that the district court ... proceeding in the case was held at Yakima City, but at the time of rendering judgment was held at North Yakima, to which the county-seat and the court-house had been removed ... " (42 U.S. 492, 507).

It was a bleak picture. In a matter of months, Yakima City lost more than two-thirds of its population, dropping from more than 500 to fewer than 150. The railroad's power play seemed designed to cause the full extinction of the first settled town in the Yakima Valley and Yakima County's first county seat, which was soon to lose even that last distinction.

The railroad lost in the territorial District Court, a decision upheld by the territorial Supreme Court. The railroad was ordered to either relocate its station to Yakima City or move that town -- lock, stock, and barrel -- to what was now called North Yakima. The railroad appealed, but in the meantime largely complied with the lower court judgment, trundling more than 100 buildings on horse-drawn rollers from Yakima City to the spanking new North Yakima, leaving the old town stripped nearly bare. As Yakima City, founded by pioneers 20 years earlier, grew smaller and weaker, North Yakima, dreamt up by faceless railroad functionaries the day before yesterday, grew bigger and stronger. And while it may have seemed generous of the railroad to move the old town for free, it actually served its purposes by relieving it of the need to do much building at the new site.

By the time the railroad's appeal was heard in the U.S. Supreme Court, the issue was factually moot. North Yakima was booming, Yakima City was dying, and there was really nothing to be done about it. When the Supreme Court overturned the lower courts' decision and ruled for the railroad, it was meaningful only to the extent that the decision might be precedent for deciding future lawsuits.

Not all of the U.S Supreme Court justices agreed. There were three dissenters, one of whom was famed jurist John Marshall Harlan (1833-1911). The dissent framed the issues as they really were:

"A railroad company builds its road into a county, finds the county-seat already established and inhabited, the largest and most prosperous town in the county, and along the line of its road for many miles. It builds its road to and through that county-seat. There is no reason of a public nature why that should not be made a stopping-place. For some reason undisclosed — perhaps because that county-seat will not pay to the managers a bonus, or because they seek a real-estate speculation in establishing a new town — it locates its depot on the site of a 'paper' town, the title to which it holds, contiguous to this established county-seat; stops only at the one, and refuses to stop at the other; and thus, for private interests, builds up a new place at the expense of the old; and for this subservience of its public duty to its private interests we are told that there is in the courts no redress" (142 U.S. 492, 509-510).

Brushing aside the majority's reasoning that the courts could not compel the railroad to stop at Yakima City because Congress had not specifically named the town as a necessary stopping place, the dissent's author ended with, "I do not so belittle the power or duty of the courts" (142 U.S. 492, 510).

Much too little, far too late. North Yakima, the invention of railroad executives, would go on to grow and prosper; the Yakima City of the pioneers would wither and nearly die. Before too many years had passed, it would even lose its name.

Yakima and Union Gap

Blessed with the railroad and the county seat, North Yakima grew rapidly. In the 1890 Federal census, the population of all of Yakima County was a mere 4,420. Ten years later it had more than tripled, to 13,462. In the same span, the town of North Yakima grew by 105 percent, to 3,154. By contrast, the 1890 census showed only 196 people in Yakima City, a town that had had more than 500 residents just five years earlier. But Yakima City would not die, and in fact would undergo a slow-motion rebound of sorts in the coming decades. In the 1900 census, its population had grown to 287, but it took until 1930 for it to reach its pre-railroad level of more than 500.

There would be one final indignity. By 1910 the population of North Yakima had exploded to more than 14,000, Yakima City's had dropped back to 263, and the proximity of two towns using the word "Yakima" was beginning to rankle and confuse. In 1917, by an act of the Washington State Legislature, the name of Yakima City was formally changed to "Union Gap," and has remained so ever since. The following January 1, North Yakima became simply Yakima, now the only town on the map to use that name. More than a half century after Dr. Goodwin's wagon train stopped at the gap in the hills that separates the Lower Yakima Valley from the Upper Valley, the town he helped found would take the name of that geographical feature. In the words of a contemporary newspaper report:

"The old territorial town of Yakima City, given a legislative charter in 1883, disappeared from the map entirely, while Union Gap came in its stead" ("Three New Towns on Map of State").

Five years after Yakima City became Union Gap, a small article in a Seattle newspaper gave some indication of how the loss of the railroad had made the town nearly disappear entirely:

"So many motorists have passed through the town of Union Gap without knowing there was a town in sight until they were hailed by a traffic officer and then haled to court, that complaints have been made time and again to the Commercial Club here by outraged tourists ... " ("Motorists Given Warning").

In a final insult, the same article referred to Union Gap, the oldest settlement in all of Yakima County and the first county seat, as "the infant town" ("Motorists Given Warning").

As Yakima grew to become by far the largest city in Yakima County, the second largest in Eastern Washington, and the eighth largest in the state (2013), its boundaries expanded in all directions, and eventually the dividing line between that city and Union Gap became more political than geographical, with the northern reaches of the smaller town blending in with the southern boundary of the larger. And, just as their boundaries merged, so largely did their histories. They may be two independent cities in name, but they developed largely as one large municipality, although maintaining separate governments, school districts, and some services.

Nonetheless, the residents of Union Gap worked to maintain their independence from the usurper to the north. In 1935, the town's voters passed, by a 194-18 margin, a $23,000 bond issue to build a modern municipal water system, replacing reliance on individual wells. And a Union Gap Volunteer Fire Department came into being on November 3, 1937, when 14 town residents joined to provide fire protection to the community. It is still in operation and now provides other emergency services as well.

Union Gap Endures

Union Gap covers 5.03 square miles at an average elevation of 975 feet above sea level. Over the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, it has enjoyed slow but steady population growth. By 1940, the population reached nearly 1,000 residents; in 1960, 2,100; in 1980, 3,184; and the 2010 census counted 6,047. Today (2013) Union Gap's population is almost evenly divided between males and females, and 47.2 percent identify as Hispanic. Although it is an independent code city under state law, it is included with Yakima as a single "urban growth area" for purposes of regional planning under the state's Growth Management Act. In 2012, the voters of Union Gap elected to change their government from mayor/council form to city-manager form.

Union Gap has had the normal small-town complement of crime and scandal over the years, but nothing of sufficient infamy to merit much wider note than the local papers. Since 2001, only two murders have been reported within city boundaries.

Union Gap School District No. 2 operates the Union Gap Elementary School. As noted, the city has its own water and fire departments and, until recently, its own library. However, on December 14, 2012, it was announced that the library would be permanently closed. An attack of black mold had made its facility uninhabitable, and it was scheduled for demolition with no plans for a replacement. Library users, as members of the larger Yakima Valley Library system, will still have the use of neighboring facilities.

The town's economy moves largely in synchronicity with that of the valley, the state, and the country, and it suffered together with others during the major economic turmoils of the age, from the Financial Panic of 1893, to the Great Depression of the 1930s and the Great Recession of the 2000s. As of August, 2012, the unemployment rate in Union Gap was 10 percent, just slightly higher than the statewide average.

There are three locations in or adjacent to the town that are listed on the National Register of Historic Places: Kamiakin's Garden just outside the town's eastern boundary; the Elizabeth Louden Carmichael House, located at 108 W Pine Street; and the Alexander McAllister House, at 402 W White Street. The town is also home to the Central Washington Agricultural Museum in Fulbright Park, which features collections of heritage farm equipment and exhibits on the history of farming in the valley.

Perhaps the most renown the city has garnered outside of its immediate neighborhood has come from the world of rock music. Gary Puckett (b. 1942) grew up in Yakima and in the 1960s formed a band called Gary Puckett and the Union Gap. It went on to have several big hits, with the biggest, "Young Girl," topping the charts in 1968. The band is still active in 2013.

Union Gap had every reason to simply die when the Northern Pacific Railway abandoned it in its infancy. It would have been easy to just become a part of the rapidly growing city of Yakima and give up all pretense of independent existence. But its people refused to let go of what they had worked so hard to build, and as a result the town lives on today. It has learned to survive by providing services to its neighboring communities, and the Valley Mall in Union Gap alongside US Route 82 is the Yakima Valley's largest mix of shops and services and includes national, regional, and local retailers. The city marks the history of agriculture in the Yakima Valley and its own long story the third weekend of each August with the Central Washington Antique Farm Exposition and an Old Town Days celebration. Against heavy odds, Union Gap has endured, and it still holds a title that no one can take away -- it was and remains the first and the oldest town in all of Yakima County.