Pete Rademacher was a rugged farm kid from the Yakima Valley who became an Olympic champion boxer and then arranged a match that rocked the boxing world. He fought for the heavyweight championship of the world in his first professional fight, an achievement without precedent. His opponent was Floyd Patterson. The fight took place August 22, 1957, in Seattle's Sicks' Stadium. Patterson knocked out Rademacher in the sixth round, but the challenger was impressive in defeat. He went on to become a successful salesman, inventor, and business executive in his adopted home state of Ohio, and a much decorated figure in Washington sports history.

Learning to Box

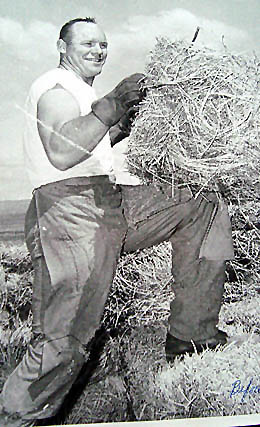

Thomas Peter Rademacher was born November 20, 1928, in Tieton, a small agricultural town near Yakima. He was the third of seven children of Herbert Smith Rademacher (1900-1993) and Thelma Catherine Rademacher (1901-1995). Herb was an apple grower with his own packing plant and warehouse. He was active in his community, serving as Grange master and school board chairman. He also coached adult baseball and youth boxing. He had been a professional boxer, fighting as a lightweight under the name Johnny Ray. Thelma, whose parents were Finnish immigrants, was an avid organic gardener and horse lover. Their first son, Thomas Peter, was called Tom throughout childhood.

Tom attended ninth grade at Tieton High School while his parents made arrangements to send him to Castle Heights Military Academy in Lebanon, Tennessee. His father was an admirer of the academy's owner, Bernarr McFadden (1868-1955), who has been called the father of American bodybuilding. McFadden promoted "physical culture," including natural remedies for health problems, and believed it and character development were as important as academics in the education of young people. In 1944, Tom and his younger brother John (b. 1930) left home for the academy. Accompanying them was their oldest sister Jean (1923-2006), who transferred to the University of Tennessee from Washington State College so she could be closer to her brothers.

"We called it a rich man's reformatory," Rademacher said with a chuckle about Castle Heights (Drosendahl interview). The cadets wore uniforms with a black stripe down the outside of light blue pant legs. He remembered town kids calling the cadets bellhops because of those uniforms and that the name-calling led to fights. The academy had a boxing trainer and that's where both Tom and his brother John learned to box and soon were winning tournaments. Tom started out as a light heavyweight (168 to 175 pounds). He also played trombone in the academy's band.

College and Golden Gloves

After graduating from Castle Heights in 1948, Rademacher went to Yakima Valley Junior College, where he studied mechanical engineering but by his own admission was more focused on athletics. He played four sports -- football, wrestling, boxing, and baseball. In baseball, he was a standout catcher and captain of the team. In football, he was an offensive and defensive lineman.

While at Yakima Valley JC, Rademacher also boxed at the Yakima YMCA and began to make a regional name for himself. By then he was going by the name Pete, explaining that it "sounds a lot meaner for the fight game" (Drosendahl interview). He won the Golden Gloves tournament in Seattle in 1949, the first of four times he would win the Northwest amateur championship.

Rademacher entered Washington State College in 1950. He initially studied journalism, but later switched to animal husbandry, with the intention of going into ranching in the Yakima Valley. He earned his Bachelor of Science degree in January 1953, taking an extra semester to finish college because of his busy sports schedule, both on and off campus.

Gaining Experience

At Washington State, he lettered in football as a 200-pound defensive guard. The college had a boxing team but Rademacher was ineligible for intercollegiate boxing because he had competed in Golden Gloves tournaments past his 18th birthday. He regularly worked out with the Cougar boxers in Pullman, however, and occasionally fought exhibition bouts during WSC home boxing matches, while continuing to compete in top amateur tournaments. He also had important training contacts in Seattle.

Rademacher won the Northwest Golden Gloves in Seattle again in 1951 and 1952. He was in a restaurant during one of those tournaments, the night before the championship bout, when he was recognized by George Chemeres (1914-2002), a wily and colorful Seattle trainer who worked with other boxers, including professionals. Chemeres invited Rademacher to his hotel room and began demonstrating how to be more effective in the ring. Chemeres showed the young fighter how to keep his fists low, inviting a punch to the chin, and then pivot and take advantage of what suddenly would be an opening in his opponent's defenses. "He taught me how to fight. What a difference it was. I started knocking everybody out," Rademacher said (Drosendahl interview).

While still in college, whenever he could get to Seattle Rademacher would meet Chemeres at the Evergreen Gymnasium on Cherry Street. Professional boxer Harry "Kid" Matthews (1922-2003) and his promoter and manager Jack Hurley (1897-1972) were among the other regulars at the gym. Rademacher would get tips from Chemeres and Hurley and spar with Matthews; their combined experience helped him improve as a boxer.

Rademacher won a fourth Northwest championship in 1953 after graduating from college. He went on to win the U.S. Amateur Championship that year in Boston, with Chemeres in his corner. One of the fighters he defeated was Zora Folley (1932-1972), who had beaten him for the Northwest crown in 1950 and would later become a top-ranked challenger for the world heavyweight championship.

Getting Married, Moving East

By that time, Rademacher was seriously in love with Margaret Sutton (1930-2007), whom he met while they were students at Yakima Valley JC. She later went to the University of Washington to study nursing. To be close to her after he graduated from Washington State, Rademacher took a job unpacking produce at a Safeway warehouse in Seattle.

Margaret and her mother wanted Rademacher to quit boxing. He said he would after winning the national amateur championship. And for a while he did. Herb Rademacher had bought some land near Sunnyside -- 320 acres of what Rademacher remembered decades later as mostly desert and rattlesnakes -- and sons Pete and John helped him install an irrigation system and plant crops.

On September 5, 1953, five days after Margaret graduated from nursing school, she and Pete got married at St. Michael's Episcopal Church in Yakima. They rented a home in Sunnyside where Margaret worked night shifts as a nurse at Sunnyside Community Hospital while Pete continued to help with the family farmland. They eventually had three children -- Susan Michele Rademacher (b. 1954), Helen Jennings Rademacher Chaney (b. 1958), and Margot Nelson Rademacher Skirpstas (b. 1960).

Rademacher had been in Reserve Officers Training Corps at Washington State, so he owed the army some active duty time. In the spring of 1954, with Margaret pregnant with Susan, they headed to Fort Benning, Georgia, where he served from June 1954 to March 1957, achieving the rank of first lieutenant.

Qualifying For the Olympics

Rademacher resumed boxing at Fort Benning, with considerable success. His biggest year was 1956 when, as a member of the U.S. Army team, he won the Chicago Golden Gloves and both the All-Army and All-Branches service championships. From there he went to the U.S. Olympic boxing trials in San Francisco, with Chemeres once again in his corner. Despite injuring his right arm, Rademacher won the tournament and a spot in the 1956 Olympic Games in Melbourne, Australia.

Because the Summer Games were in the Southern Hemisphere, they were held later than usual -- from November 22 to December 8, early summer in Australia. Rademacher turned 28 just two days before the opening ceremonies. He was listed in Olympic records as 6-foot-1 and 209 pounds, with Grandview, Washington, as his hometown. Grandview was where his parents lived, having sold their Tieton home and orchards in 1954 to be closer to the family farm in Sunnyside.

The 1956 Olympics occurred at a particularly tense time in the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union. Just weeks earlier Soviet troops and tanks had invaded Budapest, Hungary, and crushed a revolt. Tensions between those countries led to a bloody brawl between their water polo teams in Melbourne. The conflict also focused extra attention on the competition between the two most powerful Olympic teams, those from the U.S. and U.S.S.R.

Winning the Gold

There was some question about whether Rademacher would be fully recovered from his arm injury, but a lucky draw put him directly into the quarterfinals of the heavyweight boxing competition, giving him extra time to heal before having to fight. When he did, he was unstoppable. He scored three consecutive technical knockouts to win the gold medal -- defeating, in order, Czechoslovakia's Josef Nemec (1933-2008) in two rounds, South Africa's Daan Bekker (1932-2009) in three, and the Soviet Union's Lev Moukhine (sometimes spelled Mukhin, 1936-1977), shockingly, in one.

Rademacher's victory in the December 1, 1956, championship bout was a surprise, because Moukhine was undefeated in 100 fights, including three knockouts in Melbourne. Rademacher floored him three times before the referee stopped the fight. The Russian had barely landed a punch. It was a dominating performance and, from a propaganda standpoint, had the extra impact of an underdog U.S. Army lieutenant beating a fearsome Russian for the gold. Celebrating Hungarians and Americans hoisted Rademacher onto their shoulders. Tears streamed down his face and onto his medal. The U.S. Olympic Committee picked him to carry the American flag in the closing ceremonies.

His triumph made Rademacher a celebrity sports star in Washington. He was named 1956 Seattle Post-Intelligencer Man of the Year shortly after the Olympics, beating, among other nominees, two future hall of fame members, golfer Jo Anne Gunderson (later Carner, b. 1939) and hydroplane racer Bill Muncey (1928-1981).

An Audacious Plan

The Olympic championship fight marked the end of Rademacher's career as an amateur -- he had compiled a 72-7 record -- but he wasn't through with boxing. He had an audacious plan. It came to him before he went to Melbourne.

He decided that he would win the Olympic gold medal and then fight for the world heavyweight championship, something never done in a professional's first bout. The championship was vacant, Rocky Marciano (1923-1969) having retired. Archie Moore (1916-1998) and Floyd Patterson (1935-2006) were scheduled to fight for the title on November 30, 1956, and Rademacher believed he could beat either one.

Patterson won the championship barely nine hours before Rademacher won the Olympic gold medal. And Rademacher, soon to be out of the army and acting as his own matchmaker and manager, put his plan into motion. He persuaded Melchior "Mike" Jennings (1917-1985), a wealthy sporting goods store owner in Columbus, Georgia, to back him financially. Together, by offering the new champ $250,000, they got Patterson's manager, Cus D'Amato (1908-1985), to agree to a championship fight in Seattle.

Rademacher hired Chemeres as his trainer and Hurley as the fight's promoter. Hurley announced the match, which would be held on August 22, 1957, at Sicks' Stadium. Boxing officials howled, some saying the fight shouldn't be sanctioned. Sports writers scoffed, generally agreeing Rademacher had no chance to win. Rademacher welcomed the controversy, figuring it could only add to interest in the event.

Fighting for the World Championship

The fight drew 16,961 paying customers, with hundreds seeing what they could from the hill beyond the stadium's outfield wall. Hurley had insisted there would be no live television or radio coverage, but at least two radio stations filed round-by-round reports from outside the stadium. Tickets cost $20, $15, and $10.

To the delight of the hometown crowd, Rademacher controlled the early action. He even floored Patterson briefly in the second round, an unexpected development that triggered such a roar that one fan died of a heart attack during the excitement. But soon after that, the fight turned. The 22-year-old champion knocked Rademacher down in the third round. The challenger gamely fought on but Patterson knocked him down five more times and then, in the closing seconds of round six, Patterson knocked him down for a seventh time and he was counted out.

Rademacher was gracious in defeat, complimenting Patterson's strength, quickness, and fairness. He admitted no great disappointment. Instead he said how pleased he was to have successfully arranged the championship bout. The press, which had doubted him, praised his courage and character.

Although Rademacher's intention had been to retire from boxing after the fight, regardless of the outcome, offers of other matches changed his mind. He continued to be his own manager, arranging bouts with several of the day's top heavyweight contenders but never earning another title match. He retired from boxing in 1962 at age 33. His professional record was 17 wins, six losses, and one draw.

Selling and Developing Products

Before he stopped boxing, Rademacher worked as a booker and promoter for Bobby Lamar "Lucky" McDaniel (1925-1986), an expert marksman he had met through Jennings, his Georgia backer. McDaniel was the inventor of "Instinct Shooting," a method he taught to hunters, police, and others indoors, using a BB gun. He trained Rademacher in the technique and the two of them worked with clients that included the Cincinnati Reds baseball team. Rademacher even demonstrated the technique on the Johnny Carson Show, shortly after he retired from boxing.

It was obvious by then that Rademacher had organizational skills and a natural flair for promotion and sales. He also had celebrity status from his Olympic and championship fights. A developer hired him to sell houses around a country club in Medina, Ohio. He bought a house and settled his family there in June 1963. In 1965, he went to work for Hamline Products, a subsidiary of McNeil Corporation, based in Akron. After developing an indoor "Instinct Shooting" trap range for BB guns, Rademacher was hired as a salesman and product developer by Kiefer-McNeil, a division of McNeil based in Medina that sold an array of products used in competitive swimming.

In 1971 he was named executive vice president of Kiefer-McNeil, and in 1974 he was promoted to president. Among four patented products he helped develop were swimming pool lane dividers that reduced turbulence and became widely used in major competitions. Rademacher supervised installation of those lane dividers at three different Olympics, starting with Montreal in 1976. He also regularly refereed boxing matches in Cleveland and Akron.

Enjoying Retirement

When McNeil sold the Kiefer division in October 1987, Rademacher took early retirement, but soon accepted a part-time job as golf director for the American Cancer Society's Ohio Division. He developed a statewide network of volunteers and organized at least 65 fund-raising tournaments over a period of about 12 years. He then worked with North Gateway Tire Company in Medina, developing an employee rewards program, until retiring again in 2006.

More than three decades after his Olympic triumph and heavyweight title match, Rademacher began getting formal recognition for his athletic achievements. All three of his schools -- Castle Heights Military Academy, Yakima Valley Community College, and Washington State University -- added him to their halls of fame. So did two counties in Ohio, the Central Washington Sports Hall of Fame, and the Northwest Boxing Hall of Fame. In 2007, he was inducted into the Greater Cleveland Sports Hall of Fame, his eighth such honor. He also received outstanding alumnus awards at Yakima Valley CC in 1993 and WSU's Department of Animal Sciences in 2003.

Throughout his time in Ohio, Rademacher kept busy as a motivational speaker, giving hundreds of talks at schools and to various groups. His message included the rewards of thinking big and using discipline and determination to achieve goals. He also made regular appearances at community events and in parades, riding one of his inventions, which he called a Radecycle. It was an eye-catching, one-wheeled contraption with handlebars and a small motorcycle engine. Rademacher, wearing a helmet and visor, would drive it from a seat mounted inside the tall, skinny wheel which he bedecked with signs tailored for the event. He sometimes rode the thing just for the sheer joy of it. "I'd take kids three times around the Dairy Queen in Medina," he said (Drosendahl interview).

A photo in the June 1, 2010, Cleveland Plain Dealer showed him riding in that year's University Heights, Ohio, Memorial Day parade. In the image, his head is thrown back, his mouth open in a big smile. He's 81, and still the only man ever to fight for the heavyweight championship of the world in his first professional bout.

Rademacher died on June 4, 2020, at a veterans home in Sandusky, Ohio. He was 91. Daughter Margot Skirpstas told The New York Times that her father had dementia, and that his brain would be donated to the Brain Injury Research Institute in Wheeling, West Virginia, to see if blows to the head from boxing had contributed to his illness.