On February 12, 1930, Seattle writer Margaret Bundy (1904-1961) is named Associate Editor of the weekly arts, culture, and literary magazine, Town Crier. In publication since 1910, the Town Crier has just renovated its content, tone, and graphic style in attempt to remain relevant -- and solvent -- as crumbling local and national economies impact advertising and readership.

About "About It And About"

Margaret Bundy was 26 when she was named Associate Editor of the Town Crier. Already a seasoned journalist, she had written for her high school paper, the Lincoln Weekly Totem; for the University of Washington Daily during her four years at the University of Washington; and for The Seattle Star after her college graduation. The Town Crier had hired her as a columnist in 1928.

Bundy's first byline in the Town Crier appeared on April 28, 1928. Her weekly column, "About It And About," gave her a forum for opinion mixed with light social commentary. (The name is a quotation from the medieval Persian poem "The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam": "About it and about: but evermore/ Came out by the same Door where I went in.")

Her first column addressed the ever-constant dreariness of Seattle's April weather:

"Spring, at least at time of writing, has left us Pacific Northwesterners holding the well-known sack. That capricious young person is willfully dallying in some far region where the seasons that are out of jobs hang their hats; no doubt she takes a malicious delight in watching us gingerly picking our way through muddy streets" (Town Crier, April 28, 1928, p. 10).

The column's tone remained breezy and thoughtfully tongue-in-cheek throughout Margaret's two years writing it. On January 5, 1929, she wondered, "What's the use of living when heel caps wear out so fast and office furniture with rough edges snags silk hose before you even get the bill for them?" (p. 6). On the recently founded Book-Of-The-Month Club, which Bundy -- a voracious reader -- considered "silly": "To the intelligence person of independent taste, wholesome curiosity and a natural desire to think his own thoughts and live his own life, the idea of having his reading doled out to him by any individual or group of individuals is obnoxious" (May 4, 1929).

"About It And About" last appeared on January 26, 1930. After that the change in the Town Crier's format swept it away.

The New Mid-Week Town Crier

Along with Margaret Bundy's promotion, the new format shifted the Crier's publication date from Saturday to Wednesday. George Pampel (1904-1991) was editor. The format tightened, copy was peppier and fairly irreverent. News of society doings was tempered with practical suggestions for getting by in the eroding economic climate: Restaurant reviews advised which spots poured nickel coffee, which gouged coffee drinkers for a dime.

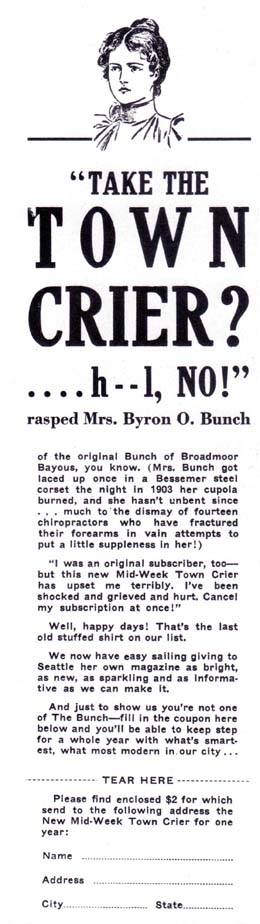

The shakeup ruffled some established readers, a situation spoofed by a series of subscription advertisements the publication ran. Typical was this, which ran on March 12, 1930, under an illustration of a frowning woman wearing a high-necked Edwardian-style blouse: "'Take the Town Crier? H--l, NO!' rasped Mrs. Byron O. Bunch … 'This new Mid-Week Town Crier has upset me terribly. I've been shocked and grieved and hurt. Cancel my subscription at once!' Well, happy days! That's the last old stuffed shirt on our list" (p. 12). The ad went on to promise new subscribers "a whole year of what's smartest, what most modern in our city."

With the changed format came streamlined graphics and more literary content. Much of the short fiction the Crier ran in the early 1930s was written by Margaret Bundy, who often kept that byline even after eloping with artist (and fellow Town Crier staffer) Kenneth Callahan (1905-1986) on November 7, 1930.

Issues of the new mid-week Town Crier evoke a sense of Seattle's artists, actors, writers, and musicians pressing their shoulders together to block the Depression's enveloping chill. Society weddings are still announced, but alongside articles on how Seattle Goodwill Industries helped homeless women, wry blurbs -- as suicide rates climbed -- about how the Smith Tower observation deck's enclosure bars thwarted jumpers, and character sketches of Pike Place Market vendors.

Human Interest

Much of the new human-interest coverage was Margaret Bundy's work. An interview with a theatrical promoter that ran June 25, 1930, began, "Seattle is a freak show town. Whether a show will go big or flop here is a moot question until the run is over. A thing that goes big in other cities will flop in Seattle, and the flops are just as likely to do big business" ("A Showman Talks").

An extended essay imagining a ramble through the city began:

"A city's streets to me are like the wrinkles on an old face. They depict the comedy and tragedy of the life that has passed there; in short, they reflect character. That is why cities that are too spick and span and new do not appeal to me; they are like the faces of college youths, over which life has not yet left its mark. And model cities — poor things! They are as bereft as eugenic babies" ("Some Seattle Streets").

Offering advice for what she called "downtown slaves," Bundy mused:

"People with reduced income (and aren't we all) can get a lot of cheer into their little hearts by visiting in person the big public market — I mean the one above the waterfront. Just to see food so cheap is warming to the soul. Here the lowly nickel can be made to assert itself in the grand manner, for will it not purchase enough fresh vegetables for a whole meal?" (September 24, 1932).

Town Crier's Demise

As the economy worsened, advertising revenue grew thin. The Crier cut its page numbers, then slashed staff salaries in half. Margaret Bundy Callahan's last appearance on the publication's masthead, and her last byline, appeared on July 19, 1934. The article, "And Points South," was a report from Panama and Cuba in which -- read the subhead -- "our cross-country correspondent gives an interesting resume of some of the circumstances whereby the citizens of Havana and Panama City resent the attitude of neighboring nations" (p. 8).

After her Crier years, Margaret Bundy Callahan reviewed art exhibits and wrote human interest stories on a freelance basis for The Seattle Times, filing her final story a few years before her death. Her son Brian Tobey Callahan (1938-2013) compiled and edited his mother's journals and unpublished work, issuing the compilation Margaret Bundy Callahan: Mother of Northwest Art in 2009.

The Town Crier soldiered on after Margaret Bundy's departure. In 1936, the publication was again revamped, including a complete staff turnover. The new design, replete with garishly tinted photographs and artless illustrations, completely lacked its predecessor's streamlined charm. The publication became bi-monthly, then monthly. It ceased publication in November 1938.