Primarily known for his historical novels of early Oregon country -- Trask, Moontrap, and To Build a Ship -- Don Berry lived and worked from 1974 until his death in 2001 as a writer, painter, musician, sculptor, instrument maker, poet, and Zen practitioner on Vashon Island, in Seattle, and at Eagle Harbor on Bainbridge Island. He ventured into educational software in the pioneering days of computers, authored scripts for adventure films, wrote commissioned books, and built a website called Berryworks for his own unpublished fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and philosophy. Berry developed his writing skills with science fiction stories in the 1950s, but it is his trilogy of novels and his non-fiction history A Majority of Scoundrels (all written and published between 1960 and 1963) for which he is best remembered. With them, he helped create a new Northwest fiction style. Journalist Jeff Baker has called him "Reed's Forgotten Beat" for his work, his practice of Eastern metaphysics, and his longtime friendship with poets Gary Snyder (b. 1930) and Philip Whalen (1923-2002), an association that began at Reed College in Portland in the 1950s. Berry's novels, and Scoundrels, were republished between 2004 and 2006 by Oregon State University Press.

Rough Beginnings

Don George Berry was born exactly at midnight on January 23, 1932, in Redwood Falls, Minnesota, to musician parents. His father played banjo and his mother, who was one-quarter Indian of the Midwest Fox tribe, was a singer in swing bands. Both parents were alcoholics who separated when Berry was 2 years old. He continued to live with his mother and they moved frequently. When Don was 16 they were living in Vanport, Oregon, outside of Portland, in a housing project that had been shabbily built for Kaiser Shipyard workers during World War II. On Memorial Day in 1948 the Columbia River broke through a railroad embankment that served as a dike, starting a flood that left 18,000 people homeless and killed at least 15.

Berry helped sandbag the river and saw his own name listed among the dead. He took this as a gift from heaven and took off, never contacting his mother again. He moved in with friends in Portland until he finished his senior year at Roosevelt High. A bright and popular student with a love of science and math, Berry was elected student-body president, finished high school with honors, and received full scholarships in mathematics to both Harvard University and Reed College. He chose Reed.

At Reed

Don Berry attended Reed College from 1949 to 1951 and his time there was life-changing. Although he enrolled in math, he took calligraphy and graphic arts courses from teacher and calligrapher Lloyd Reynolds (1902-1978), and his interest shifted primarily to the arts. While at Reed, Berry met poets Gary Snyder and Philip Whalen, as well as his future wife Wyn. Wyn Berry later described Lloyd Reynolds as an extraordinary teacher:

"When you took Lloyd's class you got a complete education and a different way of thinking about life. It was a wonderful class. I don't know what those three men started out taking but like many, many other people who thought they were going to be scientists or political scientists, they would take Lloyd's class and end up going in a different direction. He was very instrumental in his students' lives" (Kajira Wyn Berry interview).

Berry practiced Sumi painting and sculpture, which he continued throughout his life. He had taught himself Mandarin Chinese at an early age and, while at Reed, he began translating Chinese love poems. He shared a house with Snyder and Whalen. He was a gifted musician who had a natural ability to play any instrument, including drums, but he loved most playing guitar and had both a six-string and a big-throated twelve-string on which he played everything from Bach to the blues. He especially liked the old-timey blues of Lightnin' Hopkins (1912-1982), Blind Lemon Jefferson (1893-1929) and Leadbelly (Huddie Ledbetter, 1888-1949). Berry and other musician friends often threw parties, which Wyn attended.

Learning to Write

In 1955 Berry began a disciplined effort to learn to write, arising at 4:00 a.m. to practice. In the afternoons, after work at the Reed College bookstore, he painted. He began by writing science fiction, a genre he had read and collected for years. He set a goal for himself of writing a quarter-million words, or writing for two years, in which time he hoped to master the craft.

After 144 rejection slips Berry sold his first story, which was followed by more science-fiction sales from 1956 to 1958. After Sputnik went up in 1957, Berry claimed science fiction was dead, since the future had already arrived. One of his science fiction stories, "Song of the Axe," was included in a 2012 anthology of 1950s sci-fi assembled by Robert Silverberg (b. 1935).

Gaining a Family

After meeting at a Reed party, Berry and Wyn became close, and they were married at Christmas in 1957. Wyn had three children from a previous marriage: David, 10; Bonny, 4; and Duncan, 4 months. Berry loved the children and his relationship with each was different. With David, he was a hunter. With Bonny, he was a sweet, protective, and loving father, and they rode horses together. To Duncan, the youngest, he was a teacher and mentor in many spiritual and philosophical ways, a relationship that lasted for many years.

Wyn became Don's researcher, first reader, proofreader, and inspiration. She and Don were partners in parenting and in their arts. In her words:

"We had a wonderful, collaborative relationship; we leap-frogged each other. I'd have an idea and then he'd get into it and leap-frog me. It was challenging and exhilarating. We were both intense. And we were both very intent on exploring different spiritual disciplines" (Kajira Wyn Berry interview).

After living for a while on the Willamette River near Canby, Oregon, the Berrys moved to the Oregon coast and lived off the land. Don and David hunted bear, elk and deer, wild game, and ducks, and fished, and the whole family gathered wild food. It was a rich and rewarding life. Don and Wyn continued to paint, write, and photograph, and set up their own home darkroom. Don worked in black and white, beginning with a large-format, 11-by-15-inch camera.

Three Novels and a History

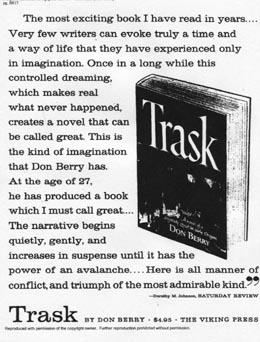

In 1958 Reed professor Dorothy Johansen suggested to Berry that he look into the story of early Oregon pioneer Eldridge Trask, who in 1848 journeyed from his home on the Clatsop Plains near Astoria and the mouth of the Columbia toward Murderer's Harbor (now Tillamook Bay). The topic indeed fascinated Berry, whose spirit of adventure was much like Trask's. His own Indian heritage drew him to the story as well. If Trask found the new country to his liking, he and his wife would settle there. It was, however, Tillamook Indian land, and Trask, as depicted by Berry, begins to consider the impact of white occupation of Indian territory. Berry saw this as a confrontation between hunter and agrarian mentalities, and he thoroughly researched the topic at the Tillamook County Museum. His efforts led to his first novel, Trask, published by Viking Press in 1960.

The book could have been just a formulaic western novel but, in Berry's hands, it broke new ground. He saw Trask as a man much like himself, impatient with settled life and intrigued by exploration. In the story, Trask needs to cross through the mountain headland of Neahkahnie, a nearly impassable approach to Tillamook country. In the words of critic Glen Love:

"Trask is aware of his historical mission … . He has seen and understood the cycle of exploration, settlement, exploitation, decimation of native inhabitants as it has occurred in the Clatsop Plains" (Love, 9).

The fact that Trask has a wife, Hannah, who sees this exploitation more clearly than her husband, adds to the novel's depth. As Berry expressed it:

"What moves a man — and ultimately the only thing that moves him deeply — is the finding of his own image, the solid configuration of himself, worked in materials of better staying quality than bone and blood. If he listens to the river and hears the coursing of blood through his temples; if he looks at a mountain and sees the strength of his own arm; if he is lost in the forest as in the darkest wells of his own mind — then that land is his and he has lost the faculty of choice concerning it" (Trask, 226).

Critics loved Trask and saw it as an enduring work of Northwest fiction. It is still regarded that way. It won a Library Guild Award and continues to be used in literature, anthropology, and history classes.

Intrigued by the early fur-trade era, Berry did additional research in the Missouri Historical Society's archives. To do so from a distance, he ordered microfilm of the materials and developed the film in his own darkroom. This led to his A Majority of Scoundrels: An Informal History of the Rocky Mountain Fur Trade, published in 1961 by Harper and Row. Wyn described the book as "pure Berry. You can hear him speaking." (Kajira Wyn Berry interview). Scoundrels reads like a novel, and despite the author's statement in its introduction that he is not a historian, the book continues to be a definitive work on its subject.

Trask's acclaim led Viking Press to advance Berry money for a second novel. With his usual energy and discipline he completed it quickly, but then destroyed it, feeling the process had not led to his personal growth in any way. With his advance money, Berry went to southern France and started writing a book he planned to call Only Mad Men. Viking changed the title to Moontrap, and it was published in 1962.

Moontrap

explores the lives of mountain men in and around Oregon City in 1850, a transitional time in the new Oregon Territory as the number of American settlers increased, bringing with them an obsession to tame what they saw as an uncivilized region. The novel's main character is Johnson Monday, a mountain man who has been living at the bend of the Willamette River near Oregon City with a Shoshone Indian wife. One day Monday is visited by an old trapper friend, Webster T. Webster, down from the mountains, and the two begin reckless adventures.

While Monday attempts to fit in with the new society, Webster cannot give up the mountain life for civilization. As Webster views the moon from a mountaintop on the day of his death, he expresses his belief that "the human race was a monstrous mistake of a god who had something better in mind" (Love, 28). Moontrap was nominated for a National Book Award and won the Golden Spur Award, given by the Western Writers of America for best historical novel that year.

To Build a Ship

(1963) completed what became a loosely-connected trilogy of novels that have been referred to as "The Trask Novels." In this third work, Berry returned to the Tillamook Valley and wrote about American settlement there from 1852 to 1854. The novel's main character is Ben Thaler, a young white man who comes West to find his fortune. Once he reaches the Oregon Coast he meets other pioneers, mostly men. The small settlement at Tillamook seems a lush paradise to the men, but when an Astorian trading ship they depend on stops coming, and with no other to take its place, the settlers decide to build their own.

While Trask needed to learn how to live in and with the wilderness, Thaler represents the new settler who has to learn how to adapt and invent in order to survive. He is "the pioneer as shaper of the future, as manipulator of the natural setting, as a man to whom the Indian is bothersome, ridiculous or irrelevant" (Love, 32).

Interesting stories aside, what most readers liked was the excellent writing in all four books, each one bringing Berry acclaim by critics and establishing him as an important author. But Berry was ready to explore new pursuits.

New Directions

The Berry family moved to a large residence they called Vista House, near Washington Park Gardens in Portland, during a time when Don and Wyn were exploring different spiritual disciplines. In 1963, Rinzai Zen teacher Joshu Sasaki Roshi (b. 1907) came from Japan and held a five-day retreat in Portland. Later the Berrys would study with Nitya Chaitanya Yati (1923-1999), a Vedantan teacher from South India. Since Berry had read the writings of the sage Patanjali in both Sanskrit and Pali, he and Yati were able to hold public dialogues.

Berry also became avidly interested in computer technology in its early years, and gained an understanding of both the technology and its great potential. In the late 1960s he went to San Francisco and composed music with a Moog synthesizer. He also began working in a newly created film department at KGW, a Portland affiliate of Seattle's KING 5 TV. Through this work he met newsman and commentator Jim Compton and began working with video producer Laszlo Pal.

The partnership with Pal resulted in the videos Crab Fisherman (for which Berry was screenwriter and music composer) and Survivor at One O'Clock, both King Screen Productions. Compton and Pal then moved to Seattle, going to work directly for King 5. Berry was expected to follow, but Wyn's photo-journalism career was soaring and two of the children were still at home. For the time being, they stayed in Portland.

The Caribbean

In 1970 the Berrys decided to live aboard a ship named Saru Be and cruise in the Caribbean. Wyn later described it as "a sea-kindly, 54' staysail ketch, jet black, with a tall 75' mast and a green crew. Living with the wind on the blue part of the planet, no boundaries, was a profound, terrifying, and memorable experience" (Kajira Wyn Berry website).

Berry left the Saru Be and returned to Portland to explore computer software. He began designing a program for children. Too far ahead of its time, Strawberry Software ended in bankruptcy. While the Berrys were in Oregon, the Saru Be was pirated from a hurricane hole (safe anchorage) in Antigua and they lost their boat. But Wyn recalled:

"That intense year in the Caribbean influenced all of us. We were so close to the bone, to the elemental in personal and experiential ways" (Kajira Wyn Berry interview).

Washington

Back in the Northwest, Berry and Wyn lived in several temporary locations, then moved onto a boat anchored at Vashon Island in 1974. Wyn rented a building on the island as a studio and soon she and Berry were living there, eventually renting a house on the island's inner harbor. Their children were now adults.

The two became core members of a group of Vashon Island artists who helped revitalize an earlier island arts group. Through a CETA (Comprehensive Employment and Training Act) grant, they helped establish the Blue Heron Arts Center. The group became Vashon Allied Arts. Berry headed its literary division and in this position he collected, edited, and published stories of island writers in a book called Islanders, published in 1978.

He continued to paint, made bronze sculptures, and took marimba lessons from Dumi Maraire (1944-1999) at the University of Washington. Berry formed Vashimba, a five-piece marimba band of Vashon Islanders that played throughout Washington and Oregon. His son Duncan played hosho with the group.

Screenwriting

Trask, Moontrap, To Build a Ship, and Scoundrels were all optioned for films, although as of 2013 none has made it to the screen. Trask has been tried several times, but has proven difficult to adapt. Probably the easiest to film would be To Build a Ship, the most visual of Berry's novels.

Berry's work with filmmaker Laszlo Pal continued through the 1980s and 1990s. He wrote scripts for Pal Productions' adventure films, including Blue Water Hunters (about the sport of spearfishing), Winds of Change, The Race Across Alaska (Susan Butcher and the 1985 Iditarod race), Three Flags Over Everest (the 1990 International Peace Climb, led by Jim Whittaker), and Sailing the World Alone (the 1994-1995 BOCA Challenge yacht race). Most of these videos received awards, and for the latter Berry received a national daytime Emmy for documentary writing.

Last Years

Berry's reputation as a respected novelist continued to grow. In the 1980s he taught creative writing at the University of Washington and Portland State University and spoke at regional writers' conferences in Washington and Oregon. The Berrys divorced and Don rented an apartment on Seattle's Capitol Hill, where he continued to write and create computer art and music. He also learned to tango and, as with most everything he tried, he was good at it.

Berry then bought a houseboat, Adriana, and lived alone on the water, in Bainbridge Island's Eagle Harbor. Meeting other boat people who lived unanchored and floating free led to some Berry's his finest and last writings, a collection he titled Magic Harbor Stories and published on his website, Berryworks. Here he built a collection -- or, as he called it, an "eclection" -- of new and unpublished writings, metaphysical pieces, computer art, and poems.

When asked by scholar Glen Love in an interview, "Do you consider yourself a Northwest writer?" Berry's response was "Yes" (Love, 44). But primarily he thought of himself as an artist:

"Berry … recited a parable of an explorer for whom it would not be thought to be strange if he were to explore mountains and rivers and deserts and forests. The creative impulse which underlies all art and all life is everywhere alike, and it may be tapped at any number of points" (Love, 44).

For Berry, each art, each endeavor, took him on a journey of discovery. He did not value his writing over his other accomplishments, but in the last years of his life he expressed the opinion that of all the things he had accomplished, he likely would be remembered for the books.

Don Berry left a list of his professional accomplishments on his website, Berryworks (www.donberry.com), and a collection of his papers and manuscripts resides in the University of Oregon archives. Following his death in February 2001, Oregon State University republished his three novels, Trask, Moontrap, and To Build a Ship, in 2004, followed by Scoundrels in 2006; all four are still in print in 2013. In connection with their republication, friend and poet Gary Snyder wrote:

"[Don Berry's novels] are all remarkable books. Historically well researched, accurate, precise to the details, marvelously evoked, and not gaudy or exaggerated in their invocation of fur trade and pioneer times … . Don Berry's literary and cultural contributions … [make] him a pre-eminent figure in Northwest letters" (Snyder).