After moving to Seattle in 1960 to teach at the University of Washington School of Art, Robert C. Jones established himself as one of the Northwest's most prominent abstract painters. A superb colorist, Jones based his compositions on the curves of the human form and simple geometries of the landscape, brushing and scraping layers of pigment to create complex, gestural, energized surfaces. Trained at the Rhode Island School of Design and in an intensive summer workshop with famed New York abstract expressionist Hans Hofmann (1880-1966), Jones remained true to Hofmann's principles. He didn't strive to reproduce the physical appearance of a person or landscape but its essence. After Jones retired from the UW in 1995 he did some of the most liberated, expansive work of his career. His exhibition history included solo shows at Seattle Art Museum, Tacoma Art Museum, The Whatcom Museum (Bellingham), and the Hallie Ford Museum of Art (Willamette University, Salem, Oregon). In 2003 he was honored with a $25,000 award from the Flintridge Foundation, bestowed on West Coast artists "of highest merit." In the Seattle arts community, Jones and his wife, the painter Fay Jones (b. 1936), earned admiration not only for the excellence of their artwork, but for their generosity and goodwill to other artists.

Cartoons and War Planes

World War II loomed over Bob Jones’s New England childhood and he stayed informed about it through LIFE magazine as well as cartoon strips featuring wartime heroes and their glamorous paramours, and the smooth, curvy forms of the latest airplanes and automobiles. Jones admired the cartoon artists of the day, from The New Yorker to Stars and Stripes, especially the work of Bill Mauldin (1921-2003), who had the audacity, in his series "Up Front," to present General Patton as Caesar. Jones later recalled:

"His drawings were terrific and I was interested in the war, the airplanes, the shapes. I can remember the shapes of the wheel covers — fantastic. There was another cartoon called Smiling Jack by Zack Moseley (1906-1993). He was always drawing planes that were almost straight off the drawing board — almost before they appeared in combat — just beautiful planes, very very sleek" (Farr interview).

Jones also admired Milton Caniff, (1907-1988) who drew the realist cartoon strip, Terry and the Pirates. But it wasn’t just the shapes of planes and glamorous cartoon characters that stuck in Jones’s mind. He’s always been attracted to the look and feel of automobiles. “My friend Steve McClelland can tell you every bird and bush. I can tell you if it’s a Ford ’37 Standard, deluxe or super deluxe. I like cars” (Farr interview).

Growing Up New England

Jones's childhood was divided between West Hartford, Connecticut, where his father, George Edward Jones (1889-1978), a lawyer, worked in the insurance business, and Granville, Massachusetts, where during World War II the family raised food on a six-acre farm. His mother, Elizabeth Quelle Jones (1895-1977), gave birth to four boys: George Edward (1918-2005), William Anderson (1920-1995), John Brooks (b. 1928), and Robert Cushman (b. October 15, 1930). A baby girl, Elizabeth Cushman, was born in 1921 and died the following year.

Growing up, Bob worked on the farm every summer from the age of 13. He liked drawing, but remembers his older brother John being the artist of the family. "I was the observer and sometimes test pilot. My brother was very mechanical. He made paintings and artificial diamonds. He made motorbikes and I tested them" (Farr interview). Two of Bob’s older brothers worked in aircraft factories at the start of the war. Later, Bill was a waist gunner on a B17, flying 35 missions, and George was a Lieutenant (JG) in the Navy on a sea-going tug.

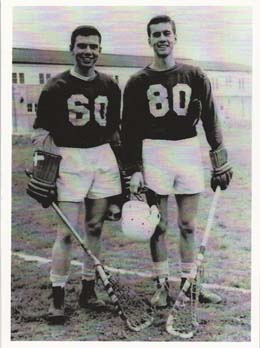

Jones attended Westfield Public High School and graduated from Mt. Hermon School, in Gill, Massachusetts, in 1948. A self-described “reasonable student,” Jones was accepted at Kenyon College largely on a recommendation from his lacrosse coach. Kenyon had a rigorous program and challenging academic standards. Two years into the core curriculum, Jones was failing an economics course -- thereby losing his eligibility to play lacrosse -- when his professor sent him over to meet Dave Straut, the painting instructor. "So I could raise my grade point," Jones said wryly. "He knew I’d get an A because Art was so easy" (Farr interview).

Becoming an Artist

The professor’s instincts, in this case, turned out to be sound. The class suited Jones perfectly. He made four paintings that spring and one of them ended up being purchased by the college. Jones heard about the summer program at the Rhode Island School of Design, signed up for it -- and never looked back. He transferred to RISD in the fall of1950 and for the next 10 years, with time off to serve in the army, was involved at the school as an undergraduate, a grad student, and an instructor. It was both a great education and a handicap, Jones recalled.

"At Rhode Island you learn how to draw the figure, in the round, in space, and then you get to a painting class and you’ve got all this blank canvas outside this round thing you’ve just made in the middle, and it was a real dilemma for almost all those Rhode Island students" (Farr interview).

In 1952, the summer before he completed his Bachelor of Fine Arts degree, Jones had an experience that caused a fundamental shift in his approach to art. One of his instructors recommended him for a summer scholarship with German émigré abstract expressionist Hans Hofmann, the influential artist, theorist, and teacher whose roster of students includes Helen Frankenthaler (1928-2011), Louise Nevelson (1899-1988), Joan Mitchell (1925-1992), Larry Rivers (1923-2002), Lee Krasner (1908-1984), and Frank Stella (b. 1936).

Jones was accepted, and that summer began the break from representation to abstraction -- a big leap for a student who’d spent two years training on principles of Renaissance figure drawing, accurately depicting models and reproducing still life compositions or landscapes. His first encounter with the master was a clash of styles. "There I was drawing this absolutely gorgeous model getting her belly button in the right place and Hofmann walks up and stands behind my easel. He looked in utter disbelief at this figure drawing, everything in the right place. Everybody else was drawing triangles, squares, pushing and pulling -- nothing representational at all. And so it was a struggle to get over” (Farr interview).

At RISD the Harris-tweed-clad instructors never touched a student’s work. You learned more or less by osmosis, Jones said. "The faculty at RISD were really New England impressionists who thought Cezanne was the beginning and the end. To hear the same language from Hofmann about abstract painting was amazing. He was very theatrical, wearing his pink smock." Hofmann would show up in sandals and suntans for his Thursday morning rounds in the drawing studio and, moving from easel to easel, take a piece of charcoal and completely rework a drawing: erasing, correcting, sometimes praising. His ultimate criticism: "Even I can’t fix this" (Farr, "Keeping Up with the Joneses").

Learning from Hans Hofmann

From Hofmann, who had a cult-like following among some students, Jones learned to consider the model as muse and the flat canvas as the primary object. "Just the simple thing: you put a mark down and you destroy the surface. You put another mark down and that mark all of a sudden does something in relation to the first mark ... . The painting is what it is about. It took me a long time to get over trying to make a landscape. I love being in the landscape, but I don’t want to replicate this landscape. The same thing with the model: There is a certain charisma, a certain aura and form that people have and you draw that, not light and shade" (Farr interview).

At Hans Hofmann’s, drawing was done in class, which meant a posed model, a stick of charcoal, and a single sheet of paper that was drawn on, scrubbed, wiped, and reused over and over throughout the week. Painting was done away from class, in individual studios, and brought to Hofmann twice during the summer for a critique, with three artists at a time presenting their work in sessions open to the public. Influential New York art dealer Sam Kootz (1899-1982), a champion of modernism -- and of Hofmann’s work -- was present at one critique, "an occasion not wasted on aggressive young students in 1952" (Farr email). Jones says he was about eight weeks into the 12-week workshop when Hofmann finally showed an interest in him: "All of a sudden he saw something that had promise" (Farr interview).

Despite Jones's modesty, his skills clearly stood out to the instructors and administrators at Rhode Island. While still an undergraduate, Jones was invited to teach a drawing class to textile and apparel design students at the school.

The Army and After

When he completed his Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in 1953, Jones was drafted into the army and sent to Korea, just after the war had ended. It was "the usual," Jones said. "Korea after the shooting. The armistice was in effect ... . It was colder than the devil, but beautiful, 30 miles north of Seoul." Initially Jones was assigned as a TIE officer (troop information and education), with a jeep to get around the countryside. "We had small squad units scattered up by the DMZ, which is why I had my jeep and traveled away from the base, quite happily, several days a week. But after my job was inspected by a lieutenant, he took my job and my jeep" (Farr interview). After that, Jones ended up at a desk job, keeping the books for a battalion N.C.O. club.

When his service was over in 1956, Jones returned to Providence, where he worked two jobs, as a janitor and a draftsman for a top-secret military project, and enrolled in the architecture program at RISD. "That was a pipe dream. I figured I’d have to make a living and I mulled this over: I wasn’t cut out to go to New York. None of the people I studied with made a living off art and it didn’t seem realistic ... . I thought: I’ll be an architect. Then I ran into things like statistics and business practices and whoa!” (Farr interview). Jones dropped out of the architecture program and, with a job teaching drawing in the freshman foundation program, began working toward his Master of Science in Education degree.

Meeting Fay

He and another RISD art student, Fay Bailey (now Jones), had been in each other’s orbits for a while when they met in 1956. Jones had dated Fay’s roommates and Fay had dated a couple of Bob’s friends while he was in Korea. Fay’s boyfriend at the time, Jim, didn’t have a car, so Bob would drive him up from Providence to Worchester to visit her. One night, through some mix up, Bob and Fay ended up having dinner together at an Italian restaurant. He remembers very well that her plate of eggplant, peppers, and meatballs, plus a beer, cost him $1.25. But after that night Bob stopped giving Jim a ride. "It just happened, that’s all," Jones said (Farr interview). Six months later, they got married.

Jones completed his degree in 1959 and in 1960 was offered a job at the University of Washington School of Art. He and Fay had been driving an old jeep, so Fay’s father traded them his DKW station wagon (a small car about the size of a Morris Minor), which they packed and set off across the country with their first two children, Tim (b. 1958) and Deirdre (b. 1960). Two more sons were born in Seattle: Tom (b. 1964) and Sebastian (b. 1966).

Teaching and Painting

At UW, Jones taught beginning classes and a popular graduate seminar with photography and electronic media instructor Paul Berger, but was always happiest teaching drawing, the nuts and bolts of it. Jones, with characteristic modesty, gives credit to his colleagues Michael Spafford (b. 1935) and Michael Dailey (1938-2009) as the intellectuals of the art faculty: "They were Phi Beta Kappa, really smart guys. They really taught," Jones said. "If I had anything to offer it was as a coach" (Farr interview).

Soon after Jones arrived in Seattle his work began drawing attention. He was accepted into the 175th Annual Exhibition of American Painting and Sculpture at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, in 1962. The following year his work appeared in Younger Washington Artists at the Henry Art Gallery at UW and in the 82nd Annual Exhibition, San Francisco Museum of Art. Over the next few years Jones’s paintings and drawings were accepted for Seattle Art Museum’s Northwest Annual -- he received an honorable mention in 1964, along with Paul Horiuchi (1906-1999) and William Ivey (1919-1992) -- and for exhibitions in Minnesota, Montana, Arizona, and California. San Francisco artist William T. Wiley (b. 1937), judging art for the Pacific Northwest Arts and Crafts Fair in 1966, gave Jones first place in drawing. In 1970 Jones had his first solo show at Francine Seders Gallery. In 1977, Bob and Fay had their first joint exhibition at the Adlai Stevenson Library, the University of California Santa Cruz.

Paint a Bawdy Life of its Own

Seattle Times critic Tom Robbins (1932-2025), an early admirer of Bob Jones's work, wrote in a 1964 review that Jones's paint "has a bawdy life of its own ... (A nice ladylike hue like pink he yanks out of the boudoir and shoves into the slaughterhouse, the alley or the marketplace.) His wild components have an orderly synthesis which is not spoiled by the violent mood that animates his gestures" (Robbins).

Another Seattle critic weighed in with a nearly opposite assessment a few years later. Reviewing a 1972 exhibition at Francine Seders Gallery, Seattle Times critic John Voorhees noted that the charcoal drawings and small paintings on display were "more cerebral than visually arresting" and concluded that "Jones’s work is so distant, so restrained that it fails to involve the viewer -- at least this one -- to any particular degree" (Voorhees).

When his work attracts the labels "cerebral" or "intellectual," Jones is mystified. Not interested in light and shade or color theory, he works from instinct. “Color wheels, matching swatches: It bores me to death,” he said. "I don’t think I am an intellectual. Flat out, that’s not what I am. I want my paintings to be very sensuous and beautiful. It’s like, you look at a beautiful sunset: I don’t want to paint a beautiful sunset, but I want my painting to do what the sunset does to you"(Farr interview).

Northwest Modernist

In 1971 the Joneses bought an abandoned farm laborers’ house in the Skagit Valley, an hour north of Seattle, and for the next 25 years would pack up and summer there. After the children were grown, Bob and Fay added a separate building with adjoining studios on the property.

By the 1980s, Jones was well established as one of the region’s major painters. In 1982 Tacoma Art Museum gave him a solo exhibition and critic Matthew Kangas (b. 1949), placing Jones in context with Northwest School artists, compared his work to Mark Tobey’s: "Not that this makes Jones a Northwest 'mystic' by any stretch of the imagination. Rather, it makes Tobey -- and Jones -- into Northwest modernists. Their modernism is based on an employment of the repeated, finite stroke which gives off a pulse of line, calm and introspection" (Kangas, "Nature Becomes Electrifying").

Kangas continued to look for Northwest referents in Jones's work in a 1984 Art in America review of Jones's exhibition at Seattle Pacific University, writing, "the best of Jones's art is a blend of Northwest landscape and geometric form or gestural markings" (Kangas, Art in America).

Jones continued his regular exhibitions at Francine Seders Gallery, which has represented a number of UW faculty artists over the years, including Spafford, Dailey, Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000), and Norman Lundin (b. 1938). Although Seders’s gallery stands apart from the more trendy, popular scene of Pioneer Square, many of the younger artists who’ve debuted in Pioneer Square galleries over the decades studied at UW with the Seders gallery set. Jones and several of his colleagues were mid-career in the 1980s, but were generally seen as elder statesmen, befitting their influential positions. Seattle Post-Intelligencer critic Regina Hackett, writing about Jones's 1985 exhibition, explained the work: "Robert C. Jones’s paintings are formidably interior -- meaning, in part that they don’t lend themselves to discussion of their 'meaning.' Although they contain allusions to figures, places, landscapes and weather states and thus refer to the world, these references are thoroughly subsumed and translated into paint” (Hackett).

Painterly Virtues

Two years later Seattle Art Museum spotlighted Jones in a solo exhibition, part of its "Documents Northwest' series honoring top regional artists. In an essay for the catalog brochure, art historian Patricia Failing affirmed the pleasure involved in Jones’s paintings, while also disclosing their depth: "The sensuality of his expressionist canvases is direct and unequivocal, but their painterly virtues are by no means easy. Intelligence, logic, and evident feeling permeate his compositions, which he pushes to the brink of overripeness and rescues in the nick of time" (Failing). She also noted comparisons between Jones and Matisse.

In 1999, Francine Seders Gallery and the University of Washington Press published the monograph Robert C. Jones, with essays by John Boylan. The book illustrates Jones's 1990s-era paintings and surveys a progression of the drawings from the loosely abstracted charcoal and graphite figures of the 1960s, through geometric studies, to a group of mixed media gestural drawings of the 1970s and 1980s -- some freely expressive, some more formal and controlled -- into a series of brushed oil or acrylic works on paper from the 1980s and 1990s that seem to serve as stepping stones, if not studies, to Jones's paintings on canvas. Boylan compares the drawings to haiku, "a balancing of words and images, layer upon layer of meaning and discovery, all within a small space, and all appearing as if effortless. It’s what has made haiku, even in translation, so timeless, and what makes good drawing so valuable and so difficult to value" (Boylan).

Mexico, Tieton, and West Seattle

In the 1990s the Joneses sold their Skagit house and studios and bought a house in Mexico, in the stately colonial city of Guanajuato, where their son Tom was a member of the symphony orchestra. Until 2009, Fay and Bob wintered in Guanajuato, where, in separate studios, they produced work tinged by the place, the climate, and cultural history they discovered. They showed their work together there in 2006 at Casa Museo Gene Byron. As of 2013 the Joneses were living in West Seattle, where each had a painting studio. After selling their Guanajuato house they added a live/work studio in Tieton, near Yakima, Washington, where they both were active with the print studio Goathead Press. Bob Jones died on December 23, 2018, at the age of 88.

As Jones explained in a catalog for his 2003 exhibition at the Hallie Ford Museum, his credo was simple. “Society pressures artists to camouflage the good time they are having. I come to my studio to paint for the sheer fun of it, for the sheer pleasure of trying to come up with something I’ve never seen before. And if I screw up, I don’t screw up the universe or anyone else’s life. There’s a possibility for freedom in art that doesn’t exist anywhere else in the world, and I love it” (Olbrantz).