Bill Holm was curator emeritus of Northwest Indian art at the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture in Seattle, a professor emeritus of art and anthropology at the University of Washington, and one of world's leading authorities on Northwest Coast Indian art. He was born in Montana in 1925 and became fascinated by Indian culture as a boy. He moved to Seattle with his family in 1937 and spent hours at the Burke Museum. As a teenager, he was invited to attend the potlatches and dances of several tribes. He taught art at Lincoln High School and began doing a systematic study of Northwest Coast art. In 1965, he published Northwest Coast Indian Art: An Analysis of Form, which became the definitive scholarly work on the subject and one of the best-selling books ever published by the University of Washington Press. He was hired in 1968 to be a curator at the Burke Museum and a lecturer at the university. He became an expert carver of masks and totem poles. He was also a painter, a discipline he returned to after his retirement from the museum and university in 1985. In 2003, the Bill Holm Center for the Study of Northwest Coast Art at the Burke Museum was launched in his honor.

Montana Boyhood

Bill Holm was born Oscar William Holm Jr. on March 24, 1925, in Roundup, Montana. His parents were Oscar Holm, an electrician, and Martha Holm, a teacher. He had a twin sister, Elizabeth, called Betty (b. 1925). Roundup was in rugged country about 50 miles north of Billings, and was ideal for firing a young boy's imagination. "It was a great place to be if you were interested in Indians, because we had these outcroppings of sandstone bluffs and hills," said Holm. "It was a very Western-looking place, a good place to play" (Interview).

Holm had become fascinated with Indians at age 9 after discovering a book on his uncle's shelves titled Two Little Savages, by Ernest Thompson Seton (1860-1946). It followed the adventures of two white Canadian boys who emulated the Indian life. The 9-year-old Holm was fascinated by the story, and he made a homemade tepee in the woods behind his uncle's North Dakota farm. The little boy's interest was so obvious that his uncle made him a present of the book, which Holm treasured all of his life. In Seton's book, the two fictional boys "never got over" their "keen interest in Indians" -- and neither did Holm (Averill, 7).

Roundup was a cowboy town, but not an Indian town. The nearest reservations were a long way from Roundup. Yet Holm read anything he could find about Plains Indian culture -- and he began rendering it. He loved drawing from an early age. "I was drawing all the time, Indians, mostly," he said. "But everything -- cowboys, Indians, whatever came into my head" (Interview).

Discovering the Burke Museum

When Holm was 12, his parents decided they had to move because of Holm's serious asthma and allergy problems. The family moved to Seattle and bought a house in the Green Lake-Woodland Park area. At first, Holm disliked the Seattle weather and forests, which "felt claustrophobic" compared to the wide-open spaces of Roundup (Interview). But he soon learned that Seattle had irresistible attractions to an intellectually curious young boy. His mother purposely chose a neighborhood within bicycle range of two libraries and the University of Washington.

Before long, Holm had discovered the Washington State Museum (now the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture) on the UW campus. He began "hanging out at the museum" at age 12 or 13, absorbing the extensive Native American collection (Interview). He was welcome to spend time there partly because he had gotten to know the director, Erna Gunther (1896-1982), who was the mother of one of his friends.

"In those days, I think there were only six people on the staff ... so it wasn't unusual to get to know the director," he said. "And she was interested in what I was doing. She could see I was pretty serious about this stuff. So I became good friends with her all the rest of her life" (Interview).

In the beginning, he was interested mainly in the museum's Plains and Plateau tribe collections. He said he "didn't care" about the Northwest Coast collection. "But you can't be around it very long before it looks interesting," said Holm (Interview). Under Gunther's guidance, he became fascinated with Northwest Coast art and objects.

Spirit Dances

Meanwhile, Gunther introduced him to her Makah Tribe friends on Neah Bay. She even took him, along with her university students, to spirit dances at the Swinomish longhouse near LaConner.

Then a teenage friend of his named Harry E. Smith (1923-1991), who later became famous as a folk-music archivist, artist, and experimental filmmaker, took Holm to some Lummi tribal celebrations near Bellingham. Smith, even at that young age, was doing surprisingly sophisticated research and recording -- "work that you would imagine a graduate student in anthropology doing" (Interview). The two teenagers would lug their recorder, a car battery, and a transformer into the smokehouse and record the ceremonies.

"It's very hard for contemporary Lummi people -- or any Northwest Coast people -- to imagine that happening, because now, the spirit dances are very closed," said Holm. "They are particular about who comes and they don't allow any note-taking or anything like that. In those days, it was a different story. So here are these two high school kids with their equipment, out in the smokehouse, doing this recording" (Interview).

Holm was aware, even at that age, that it was a privilege to witness these dances and ceremonies. The emotions, he said, were "overwhelming" (Interview). Another friend later took him to some dances on the Yakama Reservation at Toppenish. These experiences sparked a lifelong interest in Native dancing. At Lincoln High School, he organized a small group of like-minded students to perform Plains and Plateau dances, wearing regalia of various degrees of authenticity. A 1942 Seattle Times story referred to Holm and his two fellow dancers as "the school's 'white Indians,' who make their own costumes and do war dances" ("Activities"). A 1950 Seattle Times caption called him a "Swedish Indian" ("U. Dancers"). It was not unusual for non-Native enthusiasts to perform versions of Native dances. Holm would continue this hobby of Indian dancing all of his life.

"I'm not afraid to call it a hobby, because it was, and is," said Holm. "Chances are the dances and the context that the hobbyists use are pretty far from the real thing. But it varies. ... There are quite a few ex-hobbyists who are really well-respected anthropologists and ethnologists, who started as hobbyists. … They become, often, extremely knowledgeable about some facet. And that's how I started" (interview).

One other crucial association began during Holm's teenage years. In 1942, he became a summer camp counselor at Henderson Camps, later known as Camp Nor'wester, in the San Juan Islands. It was an association that would last more than 60 years and one that would shape his work and art.

To War and Back

Meanwhile, World War II intervened. Holms graduated from Lincoln High School in 1943 and was destined for the military. He was inducted into the army that summer. He was soon assigned to a field artillery observation battalion and was sent to the front lines in France as an artillery observer. His skill as an artist came in handy, because one of his tasks was to do panoramic sketching of landmarks as a guide for bombardment. However, his real job -- and a dangerous one -- was to move in ahead of the artillery, locate targets, and call in bombardments. Once, when he was strafed by cannons from German fighter planes, he "really believed that it was the end" (Averill, 15).

After the war, he was mustered out of the army with the rank of master sergeant. He went back to Seattle and immediately entered the University of Washington under the G.I. Bill for the term that began in January 1946. He faced a difficult choice -- whether to major in art or anthropology, his two passions. He chose art because he had been doing a lot of drawing and design, and because of "turmoil in faculty politics" in the anthropology department (Averill, 18). He graduated magna cum laude in 1949 with a degree in painting and then went on to earn his Master's of Fine Arts in painting from UW in 1951. His early work was in an abstract impressionist style.

"That's because that's what was being taught at the university," he said. "It wasn't my way of doing things. … I gradually slipped into doing more of the things I wanted" (Interview). When it came time for his master's thesis paintings, he created a series of Northwest Coast paintings in a style described as "realist-cum-abstraction" (Averill, 37).

Teaching and Studying Indian Culture

After getting his master's, he decided to become a public school teacher. He went back to UW to get his teaching certificate, which he earned in 1953. That year was a milestone in his personal life as well. He married Martha (Marty) Mueller, whom he had met in 1949 while both were on the staff of the Henderson Camps. With his new teaching certificate, he returned to a familiar place: Lincoln High School, from which he had graduated 10 years before. He became one of the two art teachers on staff, but in the first year, he spent most of his time presiding over study hall.

He would teach art at Lincoln for the next 15 years. Indian art and culture remained his passion. In 1953 he was invited to attend the first potlatch of the Kwakwaka'wakw people (also referred to as the Kwakiutl) after the removal of Canada's anti-potlatch laws. The potlatch was put on by Chief Mungo Martin (1876-1962), a master carver associated with the British Columbia Provincial Museum, in a new longhouse built at the museum for the ceremony. It was Holm's "first direct exposure" to the Kwakwaka'wakw culture, which would figure prominently in Holm's subsequent career (Chronology).

In 1955 he and Marty spent part of a summer kayaking through Kwakwaka'wakw villages on the British Columbia shore. They were gathering information for a major construction project: a big-house at the summer camp, now called Camp Nor'wester on Lopez Island. The completed big-house, complete with totem poles and painted walls, for years became the scene of "play potlatches" organized by the Holms for the campers (Averill, 25).

In 1957 the Holms invited Mungo Martin to come to a "play potlatch" at the big-house. One of their colleagues said this was a little like "inviting Michelangelo to come and look at our charcoal drawings!" (Averill, 25). Martin was overwhelmed at what he saw and during a speech during the ceremony he said, "I will be ashamed to go back home and tell what you are doing here on Lopez Island, while my own young seem not to be interested in learning the traditional ways" (Averill, 26). Martin was so pleased at what he saw that he made Holm a series of recordings of traditional songs to use at the camp. He also gave Bill and Marty Holm names in the Kwakwaka'wakw language. Bill's was Namsgamuti (He Speaks Only Once). This was the first of several tribal names bestowed on Holm and his family over the years. He and his family considered these names among their "most treasured possessions" (Averill, 28).

B.C. Provincial Judge Alfred Scow (b. 1927), a tribal elder, was once asked why "such privileges were given to Bill Holm" (Averill, 28). Scow replied, "He has been a respectful student of our tradition, who took pains to learn Kwakwala. He is a very thorough art historian" (Averill, 28).

Holm the Carver

Carving -- of totem poles, masks, and even entire canoes -- became one of Holm's key interests. In 1962, he spent two months visiting museums in the U.S. and Canada to study and photograph old masks used in Kwakwaka'wakw ceremonies. Then, that summer, he and Marty traveled up and down the coast to villages visiting dancers, carvers, and chiefs and asking them what they knew about the masks. In the course of this work, Holm became an expert on the form and functions of the masks -- and he eventually became an expert carver of masks himself.

"I believe that carving masks and painting boxes has helped me to understand what I'm looking at when I look at the old things," said Holm. "Because when I go to do it, I have to look at them very carefully. … I had photographed hundreds of pieces and handled them all. But until I made that one, there were things I missed" (Interview).

He was already becoming known as an authority on the old ways, some of which had faded in contemporary times. In 1961, he was invited to teach some classes at a school at Port Chilkoot, near Haines, Alaska, which had been established to teach indigenous arts to Tlingits. He taught there periodically until 1966 (Chronology). In 1962, he painted several large panels in Northwest Coast style, used as backdrops for an exhibit of Native art at the Seattle World's Fair.

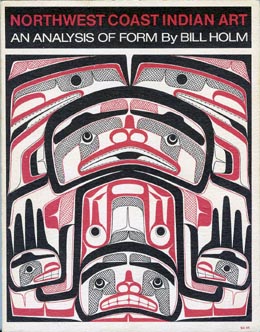

Meanwhile, Holm had written a research paper in 1958 for his longtime museum mentor, Erna Gunther, "laying out his informal observations of the structure of northern Coastal art" (Chronology). She sent it on to the University of Washington Press. After more systematic research and more documentation, it was accepted by the UW Press and published in 1965 with the title, Northwest Coast Indian Art: An Analysis of Form.

It became nothing less than "the theoretical foundation for the new discipline of Northwest Coast Indian art history," according to one of his fellow scholars (Averill, 40). It also became a top-seller at the UW Press. As of 2013, it remained one of the top 15 books ever published by the UW Press and was in its 19th printing. Art historian Aldona Jonaitis said, "He has defined the field. Very few art historians have done that" (Averill, 40). In 1966, the book won the Washington State Governor's Writers Award (today known as the Washington State Book Awards).

At University of Washington

Yet he still was an art teacher at Lincoln High School. That was about to change. In 1968, he was hired by the University of Washington for two interrelated jobs: lecturer at the university, and curator of education at his old stomping grounds, the Burke Museum. His teaching duties consisted of three courses per year: Two-Dimensional Northwest Coast Native Art, Three-Dimension Art (sculpture), and Ceremonial Arts: Dance and Drama of the Northwest Coast. These courses remained the same for many years, although one thing changed significantly: "Those classes started out with about 50 people, and ended up with 250, in a big lecture hall," said Holm (Interview).

In 1974, he was named full professor of art history and adjunct professor of anthropology. The title of Curator of Education was short-lived; soon he was named Curator of Northwest Indian Art, a post he held at the Burke Museum until his retirement in 1985. Some of his most visible early contributions to the Burke can still be seen, towering outside the building. When the new museum was built, Holm asked the architect why there was a big open space in the middle of the building. The architect said it was for the tall totem poles. "I said, 'What tall totem poles? There are no tall totem poles at the Burke,'" said Holm. "He just had a notion that there were some big totem poles somehow" (Interview).

So Holm took it on himself to make some. He spent several summers in the San Juan Islands carving four huge totem poles and then transporting them to the Burke (Interview). Today, they stand in front of the museum, along with a large horizontal whale figure, also carved by Holm.

Holm's writing and scholarship career was busier than ever. In 1976, he embarked on a year-long fellowship from the National Endowment for the Humanities and traveled Europe, photographing hundreds of Northwest Coast objects that had been dispersed to public and private collections.

In 1977, he received his second Washington State Governor's Writers Award for Form and Freedom: A Dialogue on Northwest Coast Indian Art, co-written with Bill Reid (the book was subsequently re-titled Indian Art of the Northwest Coast: A Dialogue on Craftsmanship and Aesthetics). Then in 1981 he won his third Governor's Writer's Award for a fascinating project that had consumed Holm since 1962, Edward S. Curtis in the Land of the War Canoes: A Pioneer Cinematographer, co-written with George Irving Quimby (1913-2003).

Remaking a Classic Film

Holm had discovered that the Field Museum of Chicago had a copy of pioneer photographer Edward Curtis's 1914 film, In the Land of the Head-Hunters, a dramatic depiction of life among the Kwakwaka'wakw. He and Quimby, the Burke's director, agreed to collaborate on a restoration of the rare film. Holm realized that some of the elders might remember the making of the film, so he and his family -- which now included daughters Carla and Karen -- sailed up the coast with the film and a projector. They showed it to the elders, and some did remember it after 53 years. "Many people recalled amusing incidents during the filming: How a dancer in a canoe fell when the canoe struck rock, how Curtis paid the men to shave off their mustaches, and how the unfamiliar old-style abalone-shell nose rings tickled!" said Holm (Averill, 53).

The audiences also spontaneously began singing during some of the movie's scenes, which gave Holm an idea: They could record a soundtrack to the silent film. In 1972, Holm organized a recording session on Vancouver Island, which included songs and improvised dialogue, sometimes featuring the voices of the original actors. The restored film, with the title revised to the more accurate In the Land of the War Canoes, was re-released and remains commercially available. Holm and Quimby told the entire story in their 1980 book.

Holm curated a number of exhibits at the Burke and elsewhere. One of the most notable was Smoky Top: The Art and Times of Willie Seaweed at the Pacific Science Center in 1983, which celebrated the work of a master Kwakwaka'wakw artist. In 1988, he received his fourth Governor's Writer's Award, for Spirit and Ancestor: A Century of Northwest Coast Art in the Burke Museum. He also won a Washington State Governor's Art Award, in 1976.

He also continued to have an impact on his many students over the years. Marvin Oliver, who later became an influential Indian artist and teacher, recounted his feelings about having Holm as a teacher. "(I) told myself no white guy was going to teach me about Native art -- until I met him," said Oliver in 2006. "It was his undying sensitivity to Northwest Coast art and his respectful approach. I wanted to teach Northwest Native Art like him because there were way too few people doing it" (Seven).

Bill Holm, Painter

In 1985, at age 60, Holm took early retirement from the Burke Museum, formally ending an association that dated back nearly 40 years, to when Holm began "hanging out" at the museum as a young boy (Interview). However, he never really ended his association; he was named curator emeritus at the Burke and professor emeritus at the university and he continued to work with both institutions. Yet he now had more time to devote to one of his passions: painting.

In his home studio in Shoreline, perched high above Puget Sound, he painted historic scenes in a realistic style, using his extensive knowledge of Native American culture. "I don't really think of them as fine art," said Holm. "They are pictures of times, or incidents that I can imagine, based on a lot of study of the culture" (Interview).

For instance, he painted several canvases depicting the earliest contact between the Indians and Europeans in the Northwest waters. He meticulously renders the style of canoe, the type of Spanish ship, the design of the blanket -- down to the tiny braids on the inside of the blanket. His paintings were not confined to Northwest Coast culture. He also depicted Plateau and Plains Indian scenes. For instance, Spring Hunt, a 1987 painting, depicts a Plateau hunter riding through the sage "just north of the big bend of the Columbia, with the Horse Heaven Hills in the distant background" (Sun Dogs, 98).

He may not have considered it fine art, but others do. In 2000, a lavish book of his paintings titled Sun Dogs & Eagle Down: The Indian Paintings of Bill Holm was published by the University of Washington Press. Author Steven C. Brown wrote that Holm's paintings are "born not of a romanticized retrospection, but rather of a profound respect for the individuals, the cultures, the historical situations, and the realities of those times" (Sun Dogs, 8). Holm sold his paintings directly through commission or through the Stonington Gallery in Seattle's Pioneer Square. As for his masks and other carvings, he chose not to sell those commercially.

In 2003, a new research center was established at the Burke Museum, called the Bill Holm Center for the Study of Northwest Coast Art. The center was the brainchild of Robin K. Wright, Holm's successor as the curator of Native American art at the Burke, and George F. MacDonald (b. 1938) the Burke's director at the time. Wright said she "wanted to assure Holm's legacy will continue into the future" ("NEH Grant").

The Center raised money through an art auction in 2004 and received a $300,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Holm described it as a "research center where scholars or Indian carvers or anyone involved in Northwest Coast art would be given grants to come to the Burke and study our collections." As of 2013, the Bill Holm Center remained a thriving research center at the museum.

At Work in Shoreline

Holm continued to be on the advisory board of the center and was as busy as ever as an artist. In 2013, he was working in his home studio on a project he had wanted to do for 50 years: a painted robe in Plains Indian style. It's a large tanned hide decorated with pictographs. It depicts the exploits of a warrior, just as traditional robes once did. However, in this case, it depicts Holm's adventures as an artillery observer during World War II. He was, in a sense, the modern equivalent of a scout. "I'm making a series of little pictographic vignettes, trying to show experiences that I had, but painting them as if they are old Plains Indian things," he said. "So I am freely interpreting" (Interview).

Holm continued to work at his Shoreline home and studio into his late 80s, surrounded by his totem poles, masks, carved boxes, and paintings. He died on December 16, 2020, at age 95. The Seattle Times wrote of Bill and Marty Holm's devotion to authenticity: "Their daughter Karen Holm of Bend, Oregon, remembered her teenage mortification as her dad staked out a buffalo hide on their suburban lawn, boiled brains on the woodstove for tanning leather and stuffed dead porcupines in the freezer, for quills in art-making. She also remembered a father who taught his daughters to immerse themselves in the world around them with zeal and curiosity. 'He was interested and had compassion, and he had a good ear and eye,' Holm said. 'People appreciated that and were drawn to that, and he taught that to us' ("Bill Holm, A Giant ...").