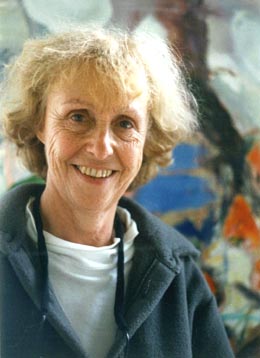

Jacqueline Barnett is a prolific painter and printmaker based in Seattle. Her work has been featured in group, thematic, and solo exhibitions since her move to the Pacific Northwest in 1985. Her abstract oil paintings tend to be brilliantly colored, expressionistic, and gestural. Her monotypes are calmer and perhaps more lyrical. In an exhibition review this writer stated, "In Jacqueline Barnett's brilliantly colored abstractions, everything – line, color, image – feeds, harbors, holds, tangles with, or explodes into everything else. No image stands alone. This large show [Foster White Gallery, 1997] ... evokes both connection and transformation" (Aorta).

Early Life

Jacqueline Barnett was born Jacqueline Marx in Manhattan on May 12, 1934. The third child born to Rene Freda Salzman (1909-1944) and the toy manufacturer Louis Marx (1896-1982), she has three siblings, Barbara Marx Hubbard (1929-2019), Louis Marx Jr. (b. 1931), and Patricia Ellsberg (b. 1936). When Jacqueline was 9, her mother died of breast cancer at age 35. The artist did not remember her mother well, and identified strongly with her father, a powerful figure both at home and in the world.

In the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s, Louis Marx innovated the mass production of inexpensive toys, selling them to stores like Woolworth's; Sears, Roebuck and Co.; and Montgomery Ward. He developed and manufactured everything from toy trucks and wind-up toys to rotund tin persons resembling one or another friend. His best-known contribution to American childhood was the yo-yo, based on a Filipino folk toy, which Marx developed in 1928 after observing a child play with the prototype.

As a result, Barnett was born into a well-to-do family replete with governesses and other caretakers that formed the center of a social whirl of friends and business associates ranging from Ed Sullivan (1901-1974) to Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890-1969) to Princess Juliana of the Netherlands (1909-2004). In 1955, the year the artist turned 21, her father, "a roly-poly, melon-bald man with berry-bright eyes," appeared on the cover of Time. Time reported that Manhattan's 21 Club held a table in perpetual reservation for "Millionaire Marx by the divine right of toy kings and the fact that he has never been known to let anyone else pay the check" (Time). Most importantly, Barnett remembered years later, at the 21 table and at other tables "there was always a place for us" (Long interview, May 9, 1996).

Louis Marx came from an opposite sort of background. He was born in Brooklyn to a German Jewish tailor and his wife, whose struggles to survive left them little time for their children. After graduating from high school at the age of 15, Marx took two jobs, one of them as an errand boy for a toy company. The artist's daughter Catherine Barnett writes in Art & Antiques that her grandfather "mastered the basics of tin toy manufacture, multiplied sales, and became the company's undisputed young star" (Art & Antiques). He was made a director, but "part of what made him so successful so young was a bull-headed self-assurance that ruffled a few too many feathers. He was asked to resign" (Art & Antiques). He went on to form with his brother a toy company that became the largest in the United States.

In the Marx family, learning was the entertainment. For decades Louis Marx took classes in philosophy, history, economics, and literature three or four nights a week at New York University and at the New School for Social Research. He memorized vocabulary words while jogging and in a cheerful way the children were stood on chairs to recite new words for the dinner guests. When, as a teenager, Jacqueline attended boarding school, her father wrote to her daily, exhorting her to "Work, work, work. Diet, diet, diet!" (Art & Antiques).

In later years Barnett reflected that she painted from "a father of intense life-force-ness" who took the stage and got the most out of life, "not getting social position really, but taking hold … . My father was a little Jewish immigrant guy who became a big toy manufacturer. What was he? He was an artistic genius who loved life … . He took hold of life and lived it, he bossed it around"(Long interview, May 9, 1996).

Barnett lived her first 10 years (1934-1944) in a Fifth Avenue penthouse in Manhattan. It was close to the Museum of Non-Objective Painting (now the Guggenheim), where the abstractions of Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) hung and exerted a profound influence on the first two generations of abstract expressionist artists. Given the proximity of the museum, various caretakers of the Marx children felt that going there was the thing to do. They went.

To Jackie Marx, the child, art meant abstraction via Kandinsky. It also meant vivid color and emotional intensity. In 1936 the American public was swept off its feet by the then little-known painter Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), whose vivid pictures were introduced in a wildly popular exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Irving Stone's novel Lust for Life (1934) registered the pathos and intensity of van Gogh's life. As a pre-teen and teenager in the late 1930s and 1940s, Jackie Marx saw van Gogh's pictures and read Lust for Life and, she later recalled, they captivated her, "both the craziness and the passion and that he saw things his own way. So it was a very lucky experience, I just started painting you know, right there … from the tube and slapping it around" (Long interview, May 9, 1996).

She attended the Dalton School in Manhattan until she was 10. Then the family moved to Scarsdale, New York, and she attended Rye Country Day School. Home was a mansion on 22 acres including a pool and tennis court. Life was happy there but, Barnett wrote, "We made our own existence and group. My Dad's life was always in New York City, so Scarsdale was like a summer resort. We always felt that we came from Manhattan" ("Notes for 2nd Interview").

An important early influence was toy designer, painter, and world-class Judo champion Cliff Freeland (1915-1987), known as "Crunch." Crunch, an employee of Louis Marx's, was a commercial artist who lived at the center of the Marx family. "Crunch loved seascapes," Barnett recalled. "He studied with the Japanese. He loved Sumi. He loved to cartoon. He didn't analyze art. He treasured art and was a successful commercial artist … . He was a gentle father figure to us all … someone quite special to our family who thought painting, drawing, was wonderful" ("Reflections," October 30, 1996). Crunch took Jackie to her first art lessons when she was 13 or 14 year old. "I remember painting trees a la Van Gogh ... twisted and strong in color ... and Mr. Bourne [the teacher, Mortimer Bourne] saying they were good and praising me for my expressiveness and freedom. It doesn't take much to let you go on the path" ("Reflections," October 30, 1996).

Young Womanhood

After graduating from the Ethel Walker School in Simsbury, Connecticut, Jacqueline went to Vassar College, majoring not in art but in English and philosophy. She graduated in 1955. The Vassar years were a time of great sociability: "It was a pretty easy thing for me to be an attractive social person … good student … Vassar girl" she recalled ("Reflections," October 30, 1996, p. 4). Like most young women of her generation, she felt the primacy of marriage and motherhood. She did not plan to be an artist.

But she continued to enjoy painting as a private pleasure, when and as she chose. "I wasn't ready to expose to the grading, observing, teaching environment of schools … because I was never part of a school, I was let to go on my own. Perhaps that was the best way for me. I didn't have to perform for anyone" ("Reflections," October 30, 1996, p. 4).

Marriage and Motherhood

After graduating from Vassar, Jacqueline Marx went to work in Washington D.C. as a receptionist for Senator Clifford Case (1904-1982) of New Jersey. There, in 1956, she met Wayne Barnett (b. 1928), a Harvard Law School graduate who was clerking for Justice John Marshall Harlan (1899-1971). They fell in love and married that year. In 1957, at the age of 23, Barnett gave birth to their son, Philip. During the following five years they had four daughters, Diane (b. 1959), Catherine (b. 1960), Claire (b. 1961), and Emily (b. 1963). The family resided in a large home, Greystone, located in Rock Creek Park, which Barnett furnished and decorated. She had ample household help, but kept her focus on her children. "I was deeply involved with them," she said, "and with early childhood education" ("Reflections" November 20, 1996, p. 5).

But she also continued to look at art -- an Arshile Gorky (1904-1948) retrospective was a revelation to her -- and she continued to paint, but sporadically, as a hobby or avocation. She took a class in a Georgetown storefront from the painters Thomas Downing (1928-1985) and Kenneth Noland (1924-2010). She was simply a paying student, yet it was important to her that they praised the energy and authenticity of her work. She kept abreast of art events, and joined the board of the Corcoran Art Museum. She kept her hand in.

She also held on to a certain identity as one who painted. She hung her paintings in her home for anyone who entered to see. An early painting, Red Geraniums (1960), is a vibrant, bold, energetic painting, prescient of later work. Through paintings like this she preserved a sense of an authentic self apart from her roles as wife and mother. People liked Red Geraniums hanging above the mantelpiece. "It was an important way that people knew what I believed … always having a painting … hanging up helped that way" (Long interview, June 26, 1996).

The Move to Stanford

In 1966 Wayne Barnett took a position on the faculty of Stanford Law School in Palo Alto, and the family -- now with five children age 9 and under -- moved to California. As a faculty wife, Barnett could take classes at Stanford, and she began taking painting classes. Her teachers welcomed her authenticity and the forcefulness of her work. Here began years of serious work. Three artists in the art department (where she became a non-matriculating student) became mentors and teachers: Keith Boyle (b. 1930), Frank Lobdell (b. 1921), and Nathan Oliveira (1928-2010).

For the next decade the Stanford Art Department became an ideal holding environment for the artist's development as a painter. She was respected and supported and stimulated. Every idea and debate swirling through the art world made a path through the department. A key debate was that between whether a painting should stand strictly for its own qualities -- color, composition, texture, and so on -- or represent something outside itself.

Barnett fell somewhere in the middle of this debate. Her abstractions typically represented an inner state, or else localities or relationships transformed by her inner experience of them. At the same time, she could become entranced by the paint itself, often flipping a painting as she worked on it. In the world of painting this could mean either looking at the subject from a different angle, or looking at a new subject (or at no subject). But in the 1970s, under the influence of burgeoning feminism, she realized that the paint "did mean something to me [beyond formalistic concerns]. It had some sense of myself ... who I was began to be explored throughout the paint" (Long interview, May 9, 1996).

The feminist politics of the 1970s brought home numerous questions and challenges to traditional lifestyles. Barnett became more conscious of the importance of her own life and of women's issues. With two close women friends, literary scholar and biographer Diane Middlebrook (1939-2007) and art critic Paula Harper (1930-2012), she attended feminist forums and went to see Woman House, an entire house recreated as an installation by Miriam Schapiro (b. 1923), Judy Chicago (b. 1939), and their colleagues. Perhaps most importantly, the sculptor Louise Bourgeois (1911-2010), whose work evokes a wide range of female experiences, exerted a strong influence.

Rather than distancing herself from familial roles, Barnett increasingly asserted her sense of her own self and life in her paintings. In the claustrophobic, energetic painting The Family (1982), heads (triangles and circles with eyes, or just eyes) crowd into a rose-colored space, the three or four faces looking in different directions, one of them askance. Among the jumble of heads and eyes the viewer can discern a distinct vulva and a small patterned throw rug. The abstraction Safe Harbor (1983) displays a curving, dark, ferocious-looking form (made by fast knife-scrapes) that harbors a soft white and rosy inner circle. This might be called mother and child and it was the maternal embrace mixed with maternal anxiety that Barnett was thinking of as she painted it. In these works and in the art department debate, Barnett took the side of wanting paint to represent her own experiences and states of being.

Frank Lobdell held up the idea of paint as valid for its own sake. He pushed Barnett and others to refrain from deciding too soon on a painting's content, to avoid closing off the painting process prematurely, to let it and the paint itself lead the painter to the end result. Story, content, something to say, Lobdell thought, could interfere because it was imposed on the process from the outside. Barnett later recalled him saying "a painting has to die one or two times until it really finds its life ..." He argued that if the story takes over too soon "you're going to kill the painting" (Long interviews, May 9, 1996, and June 26, 1996).

Barnett stood her ground but remained open. "He was a wonderful mentor, a male mentor and a very male person," she said, "but we were dealing with the same visual language, with the same high standards for ourselves" (Long interview, May 9, 1996). Partly through Lobdell's influence, her own process evolved to somewhere in the middle of the two sides.

The printmaker Nathan Oliveira provided another felicitous connection. In the early 1980s he suggested that monotypes might open up something for her. Monotypes, made by painting on a Plexiglas or zinc plate and then pressing the result onto paper, are of necessity flat. They are thinly coated with paint and the image on paper is a mirror image of that on the plate. Image predominates over texture. For Barnett, accustomed to painting in thick aggressive strokes, monotypes opened up a gentler, more imagistic side. Because monotypes could be made rather fast -- up to five a day -- they opened a door to experimentation, playfulness, a sense of great freedom. They allowed her to vastly increase her range, to expand the visual languages in which she could be fluent.

Barnett's monotypes and overpainted monotypes were more graphic than the oil paintings. They often included biomorphic figures, and hinted at narrative. Certain monotypes, along with certain oil paintings, reflected specifically female experiences and concerns. Eating the Mother (1983) shows a female figure in the shape of a dining room table with the figures of the family gathered around. The mother's legs (the table legs) reach the floor but hang loosely as if the diners were holding her up as well as eating her. The loose brushstrokes and spare composition give the picture an air of humorous calm. This portrayal of the ambivalence of motherhood is humorously reminiscent of Louise Bourgeois's house-women, in which house and woman fuse in a single figure.

At Stanford, Barnett immersed herself in cultural and intellectual currents, always in the secondary position of learner, listener, faculty wife, student. For years she audited courses in literature and in science. Literature, especially poetry, affected her work in the studio. "These classes ... allowed me to enter the rich dream spaces of images," she wrote. "I loved that space so much I wanted to do the same thing in my art" ("Reflections," November 20, 1996, p. 2).

Barnett paintings such as Red Pollock (1979) reflected her fascination with science as well as her intention to honor the painter Jackson Pollock (1912-1956) -- "an homage to the power and joy I get from looking at the Pollocks in the Museum of Modern Art" ("Thoughts on Art and Life"). During these years her stepmother, Idella Ruth Blackadder (d. 1986), who lived nearby, had a sort of living-room salon to which she would invite scientists to lecture on quantum mechanics and so on. Barnett was particularly drawn to the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle. (The Uncertainty Principle holds that the more precisely the position of a subatomic particle such as an electron is known, the less precisely its momentum can be known, and the more precisely its momentum can be known, the less precisely its location can be known.) Philosophically this made for a loophole in the absoluteness of the laws of nature. Energy, the motion of electrons, proceeds with a certain amount of randomness. Red Pollock, in Barnett's words, "is definitely talking about the randomness of energy … . The idea of there being no pure absolute truth gave me confidence and joy" ("Thoughts on Art and Life").

After a decade in the Stanford Art Department, it was time for Barnett to get her own studio. She shared space with a friend, the artist Kalani Engles. It was not long before her work began appearing in group shows, the first being a three-person show in 1982 at the Richard Sumner Gallery in Palo Alto. Between then and her first one-artist exhibition in 1987, her work appeared in 11 more group shows.

The Move to Seattle

The Barnetts lived in Palo Alto for nearly 20 years, until 1985. Wayne had been engaged in an illustrious career at Stanford Law School and had by then attained emeritus status. The children were grown. The move to Seattle was precipitated in 1985 when Jacqueline came into her inheritance (Louis Marx had died in 1982). Staying in California would have immense tax consequences, of which Wayne Barnett -- the quintessential tax lawyer -- was acutely aware. One weekend, visiting a daughter who lived in Seattle, they stumbled upon their dream house, up for sale. Within a single dizzy week they decided to buy the house (on Queen Anne Hill) and leave Stanford.

It was a sudden, felicitous move, a good time for the artist to emerge on her own terms, on her own new ground. She rented a studio in an industrial building on Western Avenue and by 1988 was represented by the Cliff Michel Gallery. Her work appeared in shows at the Seattle Art Museum, the Bellevue Art Museum, and elsewhere, and regularly at the Cliff Michel Gallery. In the 1990s she moved to the Grover/Thurston Gallery and then to the Foster/White Gallery, where she remained for eight years, until owner Don Foster (1925-2012) sold the gallery. She is now (2013) represented by the Francine Seders Gallery.

The move to the gray Pacific Northwest spurred Barnett to brighten her palette, perhaps in memory of California or "even the days in New York." "I love grays," she said, "and I love mist and I love the whole Northwest school, but ... it didn't envelope me ... also ... you want to resist the power of Morris Graves" (Long interview, May 9, 1996).

She painted with brushes, rags, palette knives, her hands. "I want the paint to go on rapidly and to be fluid," she wrote (Typed response, May 1996). She used mostly paint thinner as a medium because it made the paint move fast. She squeezed the paint directly out of the tube: "I mix it, move it, scrape it on the canvas. ... I have used a roller to spread the paint quickly. I have used an electric sander to smush the paint around. I have used noxious paint remover to take off the paint" (Typed response, May 1996)

How does an abstract painting begin? One way could be by looking out the studio window. In a reflection the artist wrote:

"I love the journey the mind makes. I was sitting looking out the window at a ferry gliding smoothly through the water, yet, parting the water ... Just the idea of painting this made me excited. The ferry would start out as a strong dominant shape. The water could be the calm area. The point of contact would open up the water and what would be discovered there? You might then paint the ferry, this same strong shape having traveled in time to another place in the painting. If you did that would be a line, and if it was a line would it divide the tow areas. Then the visual part of the painting might look too rigid and I would turn it over or perhaps unite the top and bottom with lines ... . Or if I turned the painting over the horizontal line would be a vertical and ... the world would be different. A vertical division would seem like friendlier equals and a more loving relation. More spiritual quest going up or down etc. This would be a painting" (Typed response, May 1996).

Putting Art into the World

As Barnett's work began appearing in exhibitions and as more people outside her own circles saw it, she became more conscious of the effect a painting had on its viewer. At her shows she enjoyed interacting with people and talking about the work, no matter how great or small their experience with abstraction. Under the influence of being witnessed and responded to, her work evolved. The thick, dense, energetic, gestural pieces gave way to paintings that were still intense and gestural but that had more layering, more illusion of space, more room for the viewer to participate, to enter into.

"The gestural," Barnett wrote, "reflects the passion and power of emotion. The strength of lack of inhibition, of release, of chance and spontaneity. The layering is more reflective, inter-related. The layering is what makes life interesting. It is the multi-faceted search for reality ... for going behind the apparent and finding the source ... . It was my thought that the layering is more engaging for the viewer because it allows them to enter the painting ... as space does ... while the gesture shows the power of emotion ... ." (Barnett to Long, August 8, 1996).

Artist/Wife/Mother/Friend

A recurring theme in Barnett's life and work was the dynamic between her life as wife and mother within a large family including adult children and grandchildren and the life of an autonomous artist in the studio. The dynamic involved both tension and interconnections between the two roles.

The artist's husband always supported her creative endeavors. Wayne Barnett's career as tax lawyer and law professor occupied a realm distant from an artist's studio and he had no need to compete, as sometimes happens in two-artist couples.

He admired Barnett's work and in his retirement years built her racks for the paintings and storage drawers for the monotypes. Jacqueline Barnett artworks always graced the walls of their home and Wayne worked on the lighting fixtures to "allow them to shine," in the artist's words (Long interview, June 26, 1996). He helped lift and transport the often large paintings to shows and loyally attended openings. Wayne's logical mind and orderly way of being in the world, his attention to matters electrical, fiscal, and automotive, provided a steady foil to the artist's more flamboyant, risk-taking, creative personality.

The mother-child entanglement remained a persistent theme. Tic-Tac-Toe (1994) for example portrays a large rough chartreuse and vermillion grid with the circles of the game representing nested eggs, with the X's perhaps crossing them out. "The nest has to do with maternity: protection, treasures, intimate possessions," Barnet said of this painting (Long interview, June 26, 1996).

Barnett felt conflict between the pull to spend time with her grown children and grandchildren and time in the studio, but she also felt a great congruence between raising children and painting:

"[T]he experience of raising children helped me in the painting because there is a similarity. It is the natural way to try to create the best environment for your children and to be responsive, non-controlling yet controlling to them. In the same way this is the attitude I take to painting. It has its own life. I direct and control and respond at the same time" (Barnett to Long, October 30, 1996).

Life and art also intersect in the erotic sphere in that painting can be erotic, even sexual. The gesture, the mark made in flesh-soft paint by the hand, by the motion of the body, can be aggressive or it can be sensual, gentle. Many Barnett paintings are torso-sized (about 54 by 56 inches), the size that when set on an easel required the motion of the entire body to paint. "Not only is the paint sensual," Barnett wrote, "but some of the painterly resolutions are reflections of ways I would like to be touched, softness, hidden spots, tenderness, aliveness, throbbing" ("Reflections," May 1996, p. 1). There can be a physical pleasure in just working with paints. "I love squeezing out paint onto the canvas ... swishing it around ... dragging your brush, rag, hand, palette knife through the paint." She spoke of "the sheer pleasure of being able to create something, of only listening to your own voice, of bringing something beautiful and powerful out of a void. This would be sexual in the very most organic way" ("Thoughts on Art and Life").

Connectedness -- points of conflict and contact with a loved partner, the bonds and complications of motherhood, a life enmeshed in an expansive net of family and friends -- serves and is mirrored in the artist's body of work. In Barnett's paintings and monotypes, within dozens or hundreds of works, everything -- swirls, slashes, circles, squares, the ubiquitous diagonal, the X (a double diagonal), the loops and thick gestural curves -- touches everything else.

The Crash

On January 31, 2000, Alaska Airlines Flight 231, headed for Seattle, plunged into the Pacific Ocean 40 miles northwest of Los Angeles, killing all 88 passengers aboard. Among those who perished were Coriander Barnett-Clemetson, age 8, and Blake Barnett-Clemetson, age 6, traveling home from a vacation in Mexico with their father and stepmother. Cori and Blake were Wayne and Jacqueline's granddaughters, the children of their daughter, physician Claire Barnett.

Such a tragedy becomes a fundamental turning point in the life of a family and the Barnetts were no exception as family members came together in grief and despair, and with overwhelming love and support for Claire, who had lost her children. For the artist, painting stopped.

When Barnett returned to the studio in mid-April, it was in grief and as a changed person. In October 2000 the Bradford Campbell Gallery in San Francisco presented a memorial exhibition of the resulting paintings and monotypes. Steaven Campbell's note in the catalog of the Jacqueline Barnett exhibition titled "Impact" frames these intense and powerful works:

"Over the past six months, Jacqueline Barnett has turned in despair away from, and in need and hope back to her studio ...

"In the body of work presented in this catalog, Barnett explores many of the questions and emotions that result from tragic, sudden loss. In each composition, one sees the uninhibited flow of creative energy from the soul of the artist. Her confident, bold, expressive brushstroke contains the dialogue between abstraction and figuration, the broken and the whole, light and dark. Confronted with the face of grief — her daughter Claire's, her own — Barnett paints into, through, around and back into this eclipse.

"In Barnett's own words, these paintings and monotypes are 'a thread of creative life from the darkness.' By so honestly putting herself into her art, Barnett enriches each one of us by opening that window through which we can see how another human experiences life" (Steaven Campbell).

Concerning one of the paintings, Impact (2000), Barnett reflected:

"Going through this kind of grief, I didn't know where I wanted my mind to be or where I could allow my mind to go. Thinking about the impact of the plane didn't seem a healthy place to be. But when I got to the studio [after the absence from it], it was a compelling place to go. I didn't see the impact as everything shattered in the plane. I saw the impact like a stab into my heart ... . There's a strong V in the canvas which hits into a certain spot. That was what I was focusing on, that spot, that hit ... . When I think about the crash I don't think about everything exploding. I think about just that change from one existence to the next. It's just a piercing, piercing my heart" (Halper interview, September 13, 2000, transcript pp. 6-7).

A year later she told Regina Hackett of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer that the colors and forms of feeling she painted had previously been "exuberant, even joyous. After the crash, I couldn't paint myself back into my golden life. It was over. I couldn't perceive any feeling that wasn't shaped by the loss of my grandchildren and the sorrow of my daughter, so I went with it and let the crash be my subject" ("Her Art Shaped by Loss in Plane Crash").

A Life in Art

The studio remained a resting place, a refuge, a place to spend long hours, a place to make more work. Barnett wrote:

"I ... love going to the studio. I will get up in the morning, do some reading, and then go to the studio ... I probably get there by 11 almost every day. Weekends are no break and I am in the studio until six or later ... My world and life energy are in the studio. The time spent ... is usually spent painting or printing. The place has become a resource for me, a place I like to be, to make calls, to sort out things, just to be in. It does not feel like a duty to be there. I spend a lot of time cleaning up brushes ... sweeping, mopping, tending the place. One must get paints" ("Reflections," August 1993, pp. 5-6).

Over the years Barnett experimented with three-paneled screens -- triptychs -- and with mosaic tiles. She painted with acrylics on steel to make works that could live outdoors in garden or yard. She even ventured into thin-painted, flat, calm, sand- and gray-toned paintings. Thus her work continues to unfold, most of it vibrant, energetic, and full of feeling.