On January 11, 1909, the United States and Canada sign the Boundary Waters Treaty, governing waterways shared across their border. The treaty establishes the International Joint Commission to rule on issues involving irrigation, pollution, and dams. The treaty does not specifically deal with Northwest waterways, but it will later have important implications for the Columbia River and several of its tributaries. The International Joint Commission will later hold hearings and investigations involving Columbia River pollution and the impact of the Grand Coulee Dam on the upper river in Central Washington.

Shared Waters

The origins of the Boundary Waters Treaty go back to the 1890s, when the U.S. and Canada had difficulties in apportioning irrigation waters from the St. Mary and Milk Rivers in Montana and Canada, and several rivers, including the Niagara River, around the Great Lakes.

In 1896, the Canadian government informed the U.S. that it was willing to make an agreement or treaty governing shared streams and lakes. It took the U.S. until 1902 to respond, but when it did, it proposed talks to form an international commission to "investigate and report upon the conditions and uses of the waters adjacent to the boundary lines between the United States and Canada" ("Origins"). The two countries then formed a commission, the International Waterways Commission, which began operating in 1905 but soon proved to lack the ability to implement its recommendations.

It became clear that a more comprehensive solution to border waters questions was needed. In 1907, negotiations between Canadian and U.S. officials opened in Washington, D. C. The chief Canadian negotiator was George C. Gibbons, the Canadian chairman of the International Waterways Commission. The chief U.S. negotiator was Chandler P. Anderson (1866-1936), a special legal adviser to Secretary of State Elihu Root (1845-1937).

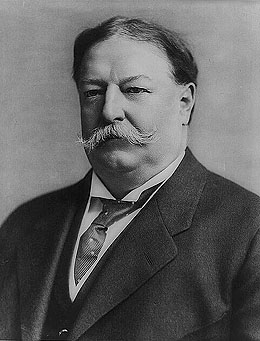

After "protracted and sometimes difficult discussions and several drafts" ("Origins"), the parties agreed on the Boundary Waters Treaty in early 1909 and it was signed by Root and James Bryce (1838-1922), the British ambassador to the United States. The U.S. Senate approved the treaty, after adding a small rider involving Sault Ste. Marie, soon after and President William Howard Taft (1857-1930) ratified it on April 1, 1909. Great Britain, which still held dominion over Canada, ratified it on March 31, 1910. It went into effect on May 5, 1910.

International Joint Commission

The treaty did not specifically mention the Columbia River or any other Northwest waters. In fact, the Columbia was not technically a "boundary water," as defined by the treaty, because it did not form a boundary between the two countries (Harrison, "Boundary Waters Treaty"). The treaty dealt with the Niagara, the Milk, and the St. Mary's rivers. Yet several of its provisions would go on to have significant impact for Northwest waters.

First, the treaty established an International Joint Commission, which was authorized to deal with questions of pollution traveling over the border. The International Joint Commission went on to investigate a giant ore smelter along the Columbia River in Trail, B.C., and grant the U.S. compensation for pollution that crossed into the U.S.

Second, and most crucially, the commission was authorized to deal with another issue that would later have profound implications for the Columbia and its tributaries: "cases involving the use or obstruction of waters" shared along the border (Treaty). There were no dams on the Columbia River in 1909, but within a century there were 14.

The commission held hearings and investigations into the Grand Coulee Dam when it was finished in 1941, and then again beginning in 1944. These International Joint Commission reports would lead, eventually, to the Columbia River Treaty, signed in 1961 and ratified in 1964, which established a joint system of water and power allocation on the shared river.