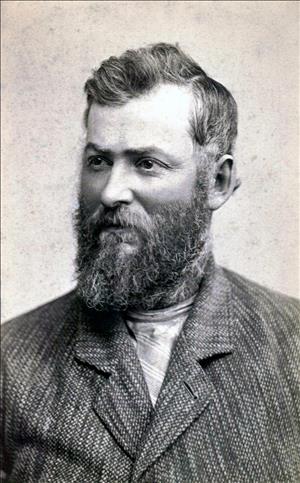

Walter Alvadore Bull was in the first wave of non-Native settlers in the Kittitas Valley just east of the Cascade Range in Central Washington. A 30-year-old bachelor and Union veteran of the Civil War, Bull arrived there in 1869 and took a 160-acre homestead east of what now Ellensburg. He was married in 1872 to Mary Jane "Jennie" Olmstead (1844-1885), and they had five children before her premature death at the age of 40. Bull later married Rebecca Nelson Frisbee (1856-1936), a widow, and with her fathered two additional children. Over the years, Bull greatly enlarged his land holdings and become a prominent citizen of the region. He served as Kittitas County's first probate judge, and in 1883 was one of the original incorporators of The Seattle and Walla Walla Trail and Wagon Road Company. Bull was financially devastated by the financial collapse called the Panic of 1893, and his health suffered as well. In the last months of his life he moved to the Okanogan, where he had a few mining claims that he hoped would pan out. There he died on March 4, 1898, and there his body remained for some time before the family could bring it home to Ellensburg for proper burial. Despite this rather sad end, Walter Bull had a major impact on the development of the Kittitas Valley, and many of his descendants live there still.

Early Life through the Civil War

Walter Alvadore Bull was born on June 20, 1838, in Albany, New York, the oldest child of John Bull (ca. 1813-?) and Sarah Fish Bull (1816-1900). When Walter was 10 the family moved to Racine, Wisconsin, where John Bull was engaged in the Great Lakes shipping business. The 1850 census records of that city indicate that Walter had two younger brothers, Lewis (1842-?) and Chas S. (1850-1930), and that the household also included John Bull's brother, Charles.

Walter attended school in Racine and lived with the family until 1858, when he moved to New York City. His activities there appear to be undocumented, but upon the outbreak of the Civil War in April 1861, he either enlisted or was conscripted. He served throughout the war in the Union Army's Quartermaster's Department, emerging unscathed from the bloodiest conflict in America's history.

After the Civil War ended in April 1865, Walter Bull went to work for the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands (known commonly as the Freedmen's Bureau), a War Department agency established in March 1865 that was a key component of Reconstruction. The bureau supervised all relief for freed slaves and impoverished war refugees, providing them with the basic necessities of life and trying to ease their path to normality. It also took custody and disposed of land confiscated during the war and its immediate aftermath. In January 1866, Bull was appointed superintendent of a "home colony" in Alabama, a position of considerable responsibility. The system of home colonies was central to Reconstruction efforts, as evidenced by this description:

"To assist freed slaves, the bureau established what were called "home colonies" in the former Confederate states. The Bureau in Alabama set aside land for home colonies, which served as employment and training centers for freedmen living there. Unlike other southern home colonies, those in Alabama were not self-sufficient. The Bureau established hospitals and also used the home colonies as distribution centers for clothes, rations, seeds, and tools. At the home colonies, the Bureau processed claims and organized services for the infirm, orphans, and the elderly. From 1865 to 1867, when massive crop failures and epidemics devastated Alabama, the Bureau made an effort to stave off malnutrition and starvation by making distribution of rations a priority" ("Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands ... ").

Working on the Railroad

It is not entirely clear when Walter Bull left the Freedmen's Bureau, but it is known that his next employment was as a contractor with the Union Pacific Railroad. He ran a crew that worked to lay the track west to join up with the Central Pacific Railroad at Promontory, Utah, which completed the first transcontinental rail line. Bull was there when the last spike was driven, and on May 30, 1869, he wrote to his mother, Sarah:

"You asked in your last letter what I was doing on the Rail Road. Well I was boss over about 50 men grading on the railroad. It wasn't much of a job but it was better and easier than working" (Letter, May 30, 1869).

He then told of his immediate plans:

"I am going overland with some teams, there is nothing new in this part of the country ... . Most all the men who were working on the U.P. have gone East and the men who worked on the C.P. have gone west. I want to see what kind of a country Oregon is, if it suits me I shall try and get me a little farm or will try and get into some kind of a job there ... . I expect it will take me 2 months to go through by land. There is a young man named Thomas Haley that is going through with me ... there is 8 or 10 of us altogether that is going — expect to start in a day or two" (Letter, May 30, 1869).

In the formal manner of the day, he signed this letter to his mother "Very Respectfully, Walter A. Bull."

The Move West

Walter Bull and friend and fellow railroad worker Thomas Haley (1847-?) did indeed head west in 1869, although the other members of the party to whom Bull referred in his letter to his mother remain unidentified, their destinations unknown. Apparently only Bull and Haley made it to the Kittitas Valley in Washington Territory, but at least two versions are told of how they ended up there. Several sources say, without further comment, that the men came upon the Kittitas Valley while on the way west to help build a road from Portland to Tacoma, and liking what they saw, felt no need to go farther. However, a more detailed account, published in the Ellensburg Daily Record in 1955, says that Bull and Haley

"went to the Dalles, Oregon, in 1869. The Dalles was a rip-roaring town on the Columbia. In front of the hastily constructed log and frame stores and saloons rolled long trains of freight wagons, their drivers covered with dust. They heard tales of the prosperous cattlemen — men talked of little else — and the long drive through the Yakima and Kittitas valleys and over the Cariboo to B.C. ... .

"They left the Dalles and rode over the trails across the Klickitat and the Satus to Kittitas. When Tom Haley first saw this valley, he always said he saw 'nothing, there was nothing to see except miles of grass and lines of trees lining the banks and creeks of the rivers and streams'" ("Passing of the Pioneers").

Walter Bull was equally taken with the scene, although his emotions were not recorded. But both he and Haley decided to call the Kittitas Valley home, joining about a dozen families and bachelors who had preceded them there, if not by much. A well-known 1904 Illustrated History of the valley dates the arrival of Bull and Haley to July 5, 1869; this seems suspiciously precise and appears to be unsupported by any documentation. But it is certain that they arrived sometime before 1869 rolled into 1870.

Bull was ready to settle down in 1869, and he took a 160-acre homestead near Naneum (often spelled "Nanum" in older accounts) Creek, east of today's Ellensburg. This would be the seed for what in time became the largest farm and ranch in Kittitas County.

Haley, taken with the talk of money to be made moving livestock, went into business as a cattle broker, driving herds from Oregon back to the Kittitas Valley for fattening on the rich grasslands, then across the mountains to markets on Puget Sound. Not until 1878 and marriage did he settle down on his homestead claim east of Ellensburg, near that of his old friend Walter Bull.

The Valley

The Kittitas Valley was part of the vast area ceded by the Yakama Tribe to the federal government in 1855 after the signing of the Walla Walla Council treaty of that year. The origin and meaning of the word "Kittitas" are unclear; in different Native dialects it and closely related words mean different things, ranging from "white chalk to shale rock to shoal people to land of plenty" ("About the County"). A settled Native American presence seems to have been late in arriving; firm evidence of permanent Indian habitation in the valley places the Psch-wan-wap-pams, also known as the Kittitas band of the Yakama, or Upper Yakama, there only from the early 1700s. Before that, bands of Indians frequented the area seasonally to dig for camas and kous (a root used to make a bread).

One of the first Europeans to enter the valley was Scottish fur trader Alexander Ross (1783-1856), who in 1814 came upon a huge gathering of Indians:

“This mammoth camp could not have contained less than 3000 men, exclusive of women and children, and treble that number of horses. It was a grand and imposing sight in the wilderness, covering more than six miles in every direction. Councils, root gathering, hunting, horse-racing, foot-racing, gambling, singing, dancing, drumming, yelling, and a thousand other things which I cannot mention, were going on around us” ("Kittitas County — Thumbnail History").

The valley is bounded on the north by the Stuart Range, on the west by the Cascades, and on the east by the Saddle Mountains and the Manastash and Umtanum ridges. Once most of the Natives had been removed to reservations, it lay in wait for the arrival of Euro-American settlers. A. J. Splawn (1845-1917), who would later settle there, first visited the valley in 1861 and gave his impressions:

"This valley, as it looked to me that day, was the loveliest spot I had ever seen — to the west, the great Cascade range, to the northwest the needle peaks of Pish-pish-ash-tan stood as silent sentinels over the beautiful dell below, where the Yakima wound its way the length of the valley and disappeared down the grand canyon. From the mountains to the north flowed many smaller streams, while the plain was dotted here and there with groves and thickly carpeted with grass. It was truly the land of plenty" (Ka-mi-akin, 160).

In 1871, John Alden Shoudy (1841-1901) and Mary Ellen Stewart Shoudy (1846-1921) came to the valley and bought the local store and 160 acres from the aforementioned A. J. Splawn. They filed a plat for the town of Ellensburg (originally spelled Ellensburgh, and named after Mary Ellen Shoudy) in 1875. The town was formally incorporated in 1884, and became the Kittitas County seat, a regional center for banking and commerce, and the focus of social life for the farming and ranching families in the valley. Long before then, Walter Bull had become one of its earliest and biggest success stories.

Hard Work Brings Great Success

Within three years of his arrival in the Kittitas Valley, Bull had met, wooed, and wed Mary Jane Olmstead, known to all as Jenny, who had come west with her father from Ottawa, LaSalle County, Illinois, in 1871. On November 23, 1872, Bull and she were married by a minister, P. B. Chamberlain, at the Oriental Hotel in Walla Walla. The wedding occurred some distance from Bull's homestead because county auditors issued marriage licenses, and Kittitas County would not be created until 1883. The Bulls' marriage license was issued by the Walla Walla County auditor, hence the site of the wedding.

Indians had grazed their horses on the rich grasslands of the valley, and ranchers from the Yakima Valley had been driving their cattle to the Kittitas Valley for grazing since early in the 1860s. There were vast acres of bunchgrass laced with multiple streams of fresh water, and most of the first non-Indian settlers in the valley also turned their efforts to raising livestock. Bull was no exception, and although his primary business was raising cattle, he also dealt in dairy cows and sheep. Over the next several years, he incrementally expanded his land holdings until he was reputed to be the largest private landowner in the valley. Different sources provide different totals for his acreage, ranging from 1,500 to more than 2,000, but they are in agreement that his ranch was for many years one of the region's most significant. Bull was also one of the first to bring irrigation to his fields, diverting water from Coleman Creek and the Yakima River. Much of the land that was not used for his livestock operations was used for growing hay, a product always in demand in cattle country and across the mountains to the west. Bull was credited with being the first to bring into the Kittitas Valley both Holstein cows and Timothy hay to feed them.

While Walter was busy building his businesses, he and Jenny were also busy building a family. From 1873 to 1880 the couple was blessed with four sons and one daughter. In order of birth, they were: John Bull (1873-1959); Lewis Bull (1874-1907); Cora Bull (later Cora Bull Wright) (1876-1972); Charles Bull (1878-1979); and Grant Bull (1880-1957). All four sons of this marriage would remain in the valley. Cora Bull married a school principal and moved to Long Island, New York.

The Seattle and Walla Walla Trail and Wagon Road Company

Getting goods, people, and livestock from east of the Cascades to the larger markets on the western side was not easy in Washington Territory's earliest days, or for many years thereafter. Oregon, where east and west were better connected, was growing rapidly, but Washington, lacking such direct communication between its two halves, was thought to be lagging behind. As early as the 1860-1861 Congressional session, a proposal was floated to appropriate $75,000 for the construction of a military road from Walla Walla to Seattle, passing through the mountains at Snoqualmie Pass and following the general path of an existing trail that could accommodate only traffic on foot or horseback. The onset of the Civil War ensured that this idea went nowhere.

During the war, there was much discussion in Seattle about creating a road across the mountains, and funds were raised from the public for the purpose. In the summer of 1865, using $2,500 raised in King County, a section of road was built starting at Ranger's Prairie (the future site of North Bend). It wasn't much, but before the year was out someone managed to force six wagons over the pass, driving home the potential of such a route.

In January 1867 the territorial legislature allocated $2,000 for further work on the road, and this sum was matched by King County. By October of that year a rough road was completed from the Black River Bridge in King County over the pass to the Yakima Valley. More money was allocated by the territorial legislature the following year and the work continued. By the fall of 1869, the road over the pass was capable of handling large droves of cattle heading west to Puget Sound markets and wagons loaded with people and goods traveling both east and west.

It was a road, but not a particularly good road, subject to long seasonal closures, slides, and damage by the elements, most notably to its many crude bridges. Maintenance was a huge problem and expense and often not possible, and from 1869 until 1883 various plans were considered to finance further improvements. These included a lottery started by Seattle pioneer Henry Yesler (1810-1892), but declared illegal before a winner was selected (Yesler reputedly kept most of the proceeds anyway). Repeated pleas to the federal government for aid were rejected repeatedly, and little improvement was made to the road for well more than a decade.

In 1883, three Ellensburg men took it upon themselves to make things right, and, they hoped, to make a profit as well. On March 13 of that year, Walter Bull, Nathan Winfield Preston (1854-1933), and H. M. Bryant (1841?-1919) signed the papers incorporating "The Seattle and Walla Walla Trail and Wagon Road Company." The corporate "objects" were stated broadly in the Certificate of Incorporation:

"The objects for which this corporation is formed are — To construct, maintain, operate purchase, lease, sell or dispose of Trails and Wagon roads together with all bridges, ferries or other boats necessary thereto throughout the Territory of Washington and to collect tolls thereon" (Article 3, Certificate of Incorporation).

In fact, the corporation's immediate plans were considerably narrower: "connecting Eastern and Western Washington Territory by means of Trails and Wagon Roads through the Cascade Mountains via the 'Snoqualmie Pass'" (Certificate of Incorporation). That road was already built, and that was the road the three men were interested in. And what they were particularly interested in was the right to impose tolls on those using the road, in return for which they would maintain and improve it. The corporation issued 10,000 shares of stock at $10 per share, for a total capitalization of $100,000. The three original investors were named as "trustees" of the corporation, and Walter Bull was designated president.

As successful as these men had been in the past, the wagon road company may have been a miscalculation. In 1886, the Northern Pacific Railroad line was completed between Ellensburg and Cle Elum, in the Cascade foothills to the west. The following year, the railroad's Cascade Division was completed, and locomotives hauling both cattle cars and passenger cars could travel between Eastern and Western Washington on tortuous switchbacks over Stampede Pass. (The Stampede Tunnel would be completed the following year.) Although the Northern Pacific had originally bypassed Seattle in favor of a western terminus at Tacoma, this would change with the opening of the route over the mountains. With the railroad in full operation, a wagon trail over Snoqualmie Pass became, if not obsolete, certainly of greatly diminished importance. The company managed to stay in business for another year or so, but it was doomed. Walter Bull, however, not yet 50 years old and still in good health, was far from ready for retirement.

A New County, a New Wife, a New Job

Eight months after the formation of the wagon-road corporation, in November 1883, the Washington Territorial Legislature created Kittitas County from a portion of Yakima County and designated Ellensburg as the county seat. Bull had been appointed in 1873 as the first postmaster of the little settlement of Naneum, which disappeared into the Ellensburg plat in 1875. Now, with no apparent legal training, he became the first probate judge for the new county. He also had mining interests in the Okanogan and continued to operate his large and successful ranch and farm in the valley. Bull also spread out into other businesses; he was for a short time proprietor of the Valley Hotel in Ellensburg, and in 1888 he purchased a general merchandise store there, Smith Bros. & Company. An economical man, Bull continued to use the company's old letterhead and receipt books, simply crossing out the "Smith Bros." name and adding his below with a rubber stamp.

Jenny Bull had died young in 1885, and in February 1889 Walter Bull married Rebecca Nilsen Frisbee, a widow 18 years his junior. Her late husband, Benjamin W. Frisbee (1836-1888), one of the first schoolteachers in the Kittitas Valley, had died the previous year. (Some sources give her birth name as "Nelson," but "Nilsen" appears correct, as her father's name was Nils.) Together they would extend the Bull clan by two: John Alva Bull (1891-1961) who would operate his own valley farm in later years, and Leland Levitt Bull (1893-1983), who became a Seattle doctor. John Alva was Bull's second son named John, so he was generally referred to as Alva.

Disaster Strikes, Death Comes

It seems that the Bulls had several quietly prosperous years together, but then the financial meltdown called the Panic of 1893 swept the land. The success of the railroads had put the Seattle Walla Walla Trail and Wagon Road Company out of business; their failure now led to the ruin of Walter Bull. It started with the collapse of the overbuilt and overleveraged Philadelphia & Reading Railroad in February 1893, followed by several other railroads and supporting industries. The crisis lasted nearly five years. It caused the failure of several banks, sent unemployment skyrocketing, and led to the loss by Bull (among many others) of nearly everything he owned. Most of his large property holdings in the Kittitas Valley were sold off to pay debts, and he, Rebecca, and their two very young sons were left with very little.

Bull's health also began to fail, no doubt caused in significant part by the shock of losing almost all that he had built up over the course of a quarter-century of hard work. Among the few assets he still had were his mining claims in the Okanogan. For reasons of both health and finances, he decided to travel there to work them, hoping to recoup his losses. He stayed on a ranch at Wild Horse Springs near Loomis with an old friend, Henry Livingston, who would live to the remarkable age of 108, having been born in 1820 and dying in 1928. Bull would not be so fortunate, if such extreme longevity can be considered fortunate; he died at Livingston's home on March 4, 1898.

Rebecca Bull traveled to Loomis upon learning of her husband's death. She sent a telegram from Coulee City to her son John: "Father died March fourth -- cannot bring body home -- wire relations east." It is unclear whether the inability to return with Bull's body was due to the weather or the family's financial situation. Whichever, for the time being Bull was laid to rest on Livingston's ranch.

Home at Last

Walter Bull did eventually make it home, although it was not until at least the next year, and perhaps longer. A newspaper clipping, undated and missing the paper's logo but quite possibly from the Loomiston Journal ("Loomiston" being a common variation of Loomis in the 1890s), reads in part:

"Henry Livingston, of Ellensburg, accompanied by E. M. Thayer, vice president of the Puget Sound Marble and Granite company, of Seattle, came to Riverside last Sunday. The object of their visit was to exhume the corpse of Walter A. Bull, buried on the ranch of Mr. Livingston in Wild Horse Spring coulee, northwest of here, in 1898 ... . The corpse was exhumed last Monday, and on Tuesday Mr. Livingston and Mr. Thayer started for Ellensburg" ("Pioneer's Body Here for Burial").

Once his remains arrived in Ellensburg, they were reburied in the Odd Fellows cemetery there, beneath a monument suitable to his status as an early and successful pioneer, paid for by his sons and Henry Livingston. His first wife, Jenny, is buried by his side.

Walter Bull's contributions to the Kittitas Valley and Ellensburg were many, and he was widely mourned. Two decades after his death, a well-known history of the region had this to say:

"He served as local probate judge at an early day and he exerted much influence over public thought and action, being a most loyal and devoted citizen and one well qualified by nature for a position of leadership. In politics he was ever a stalwart republican and fraternally he was an Odd Fellow, becoming a charter member of the lodge at Ellensburg. His worth was attested by his brethren of the fraternity, by those with whom he had business relations and by those whom he met socially. All spoke of him in terms of the highest regard and his name is written high on the roll of honored pioneer settlers who contributed much to the upbuilding and development of the county" (History of the Yakima Valley, Washington ... , 287).

The Kittitas Valley had lost a leading citizen, but it did not lose the Bulls. Five of his six sons stayed in the valley (Grant Bull moved to Seattle in 1927), mostly engaged in farming and ranching. There is today a Bull Road in Ellensburg, and numerous descendants of Walter Bull and his two wives still live in the area.