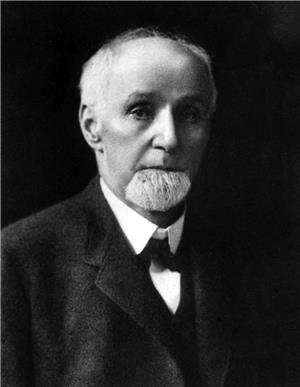

Illinois-raised Dexter Horton arrived in Seattle in 1853 as a member of what was called the "Bethel Party" (or Bethel Company), Seattle's second covered-wagon expedition. Horton worked in Henry Yesler's mill, then started a general store at 1st Avenue and Washington Street where he looked after local workers' money, thereby becoming Seattle's first "banker." Eventually he founded the Dexter Horton Bank, forerunner of SeaFirst Bank.

The Bethel Party

In the spring of 1852, Dexter Horton of Princeton, Illinois, with his wife Hannah Eliza (Shoudy) Horton (1828-1871) and daughter Rebecca, joined what became known as the Bethel Company on their journey across the plains to Oregon. Other members of this party who would, like Horton, help establish the city of Seattle, were: Thomas Mercer, his wife Nancy Brigham Mercer (d. 1852) and their four daughters; Rev. Daniel Bagley (1818-1905), his wife Susannah Whipple Bagley and their young son Clarence (1843-1932); Aaron Mercer and his wife Ellen Leonard Mercer; William F. West and his wife Jane Whipple West; Edna Whipple; and about 20 bachelors.

After unpacking and resting at The Dalles (the rapids and the town named after them where the Cascade Mountains cross the Columbia River) and after struggling through the Lower Cascades, the party arrived in Salem, capital of Oregon, on September 21, 1852. Several members of the party remained in Salem. In the spring of 1853, Dexter Horton -- after recovering from the infamous illness "ague" -- continued with Thomas Mercer to Seattle. At first Horton, who in later life became a millionaire banker and businessman, worked as a hand at Henry Yesler's mill.

He also worked at Port Gamble and in Port Townsend as a carpenter. After earning their stakes, Horton and Mercer returned to Salem to collect their families.

Upon his return, Horton again took orders at Yesler's sawmill, and his wife managed the cookhouse, preparing meals for 14 men. Horton also worked for Thomas Mercer in the town's first transfer -- i.e., moving -- business. He once said: "After I ate my dinner I went around to the shed where (Mercer) kept "old Tib" and "Charley" and hitched them up and did whatever teaming there was to do. This usually took a couple of hours; then I went to bed." The Hortons saved every penny they could and stowed their money in an old trunk.

On July 23, 1855, Dexter Horton joined Judge Edward Lander, Carson Boren, Charles Plummer (?-1866) and others on an expedition to find the best Cascade Mountain pass. The party traveled to Squak (Issaquah), then to Snoqualmie Falls, where they divided into two groups. One team used the old Hudson's Bay pack trail, the other, a traditional Indian trail. The teams met at Lake Keechelus, parted again, and returned to Seattle to discuss their efforts. These pioneers not only sought a general passage through the barrier mountains, they wanted to take advantage of gold discoveries in Eastern Washington. They also had an eye on the dream of Arthur A. Denny (1822-1899) of a direct railroad route from the East.

Dexter Horton and Arthur Denny entered the business of selling surplus stock from ships. Soon, goods were ordered directly from San Francisco. When, during the mid-1850s, Denny was representing King County at the Washington Territory Legislature in Olympia, Horton ran the business on his own. Members of the Indian nations were among his steady customers.

Horton was in San Francisco buying supplies for his store when the January 26, 1856, Battle of Seattle took place. On his return journey, at Port Townsend, he heard cannon fire. Learning that a group of Indians was attacking his home town he hired an Indian couple to paddle him to Seattle. Every few minutes his guide would pause, look around, and listen for enemies. When opposite Seattle, seeing no canoes, they quickly paddled toward the town. Coming alongside the Decatur, Horton was hailed and informed that his wife was safe on board.

One Sunday, after the battle, Horton went to the outskirts of the village to look for a stray cow. Seeing a fire burning under a big stump, he stopped and backed up to warm himself. An unexploded shell from the Decatur within the stump blew up, sending Horton sprawling. Unlike his friends, it took a long time before he found humor in the incident.

Horton's reputation for honesty and dependability led him, almost by accident, to hold money for loggers. He placed their funds in sacks and hid them in various places around his store, including deep within the coffee barrel. As his "banking" business grew, he acquired a small safe. He tagged each sack with the owner's name. After selling his Seattle business in 1866 to Henry A. Atkins -- later Seattle's first Mayor -- and William H. Shoudy, Horton moved to San Francisco to enter the brokerage business. In 1870, he returned to Seattle with a heavy steel safe and appropriate papers to establish a bank — the first in Seattle.

The Dexter Horton Bank, with capital of $50,000, first occupied a one-story stone house at 1st Avenue S near Washington Street. It was no idle boast that this squat, solid building was "fireproof," because after Horton sold his businesses, that old edifice and a stone building next door survived Seattle's 1889 Great Fire. But in 1873, Horton built another one-story building on 2nd Avenue. He was the little town's banker for 18 years, the culmination of a 34-year business career. After he sold everything to a Portland, Oregon, firm, he turned to building downtown commercial buildings such as the once famous and modern "New York Block."

After his wife Hannah died in 1871, Dexter Horton married Caroline E. Parsons (d. 1878) on September 29, 1873. After his second wife's death, he married Arabella C. Agard (1827-1914) on September 14, 1882, during a year-long sojourn in the East.

Dexter Horton, the epitome of a rags-to-riches pioneer, died in his Seattle home on July 28, 1904.