This history of Madrona Elementary School is taken from the second edition of Building for Learning: Seattle Public School Histories, which includes histories of every school building used by the district since its formation around 1862. The original essay was written for the 2002 first edition by Nile Thompson and Carolyn J. Marr, and updated for the 2024 edition by HistoryLink editor Nick Rousso.

Lake Washington Homestead

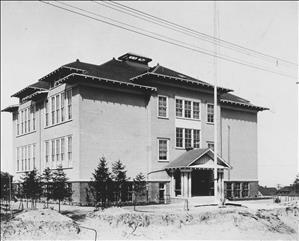

Like many of Seattle’s early schools, Madrona traces its origins to a small, humble structure. In 1890, the Seattle School Board purchased a portion of George and Emma Randell’s homestead property above the shores of Lake Washington. The old barn was converted into a two-room school named the Randell School. By 1902, the school had grown to 176 students with three teachers, and the number of classrooms doubled. An outside stairway led to the two new rooms. After a bond issue passed in 1903, the district purchased part of the adjacent five-acre Colman tract to enlarge the school site. The following year, an eight-room wood frame building was constructed in accordance with the “model school” plan of district architect James Stephen. The new school was named Madrona, apparently after the many madrona trees that grew in the neighborhood.

The old school was torn down and two portables were placed at the north end of the block. One of these portables was a two-story structure with a peaked roof, and the other was single-story. Lacking a playground, the children played in the streets or in nearby wooded lots. In 1909, the portables were demolished, and the lumber was sold to a family who built a house out of it a few blocks from the school.

Rapid Growth

Madrona School grew rapidly as the surrounding area attracted more residents. In 1916-1917, enrollment reached 505 and portables were again in use. A brick addition constructed that year contained eight classrooms, a domestic science room, a shop, auditorium, and lunchroom. Principal Henrietta Mills, who headed the school from 1904 until 1922, also coached the football team. During the 1920s, Joseph W. Graham served as principal and introduced the school’s motto of “service and good will.” Madrona pupils were encouraged to render service to the community and participate in social welfare activities.

In 1931, kindergarten began, and enrollment reached 683. In September 1942, the 7th and 8th graders left to attend Edmond Meany Junior High School, and enrollment fell to 576. At this time, the shop was remodeled into a play area and the domestic science room became a classroom. During the 1950s, Madrona continued to grow. A 1958 bond election provided the funds for a major addition. The old wood structure dating to 1904 was demolished. A brick addition, constructed on the northeast side of the property, was attached to the 1917 structure, which was remodeled to include three more classrooms. When the addition was dedicated on November 2, 1961, the school had 25 classrooms, a new auditorium/lunchroom, kitchen, covered play court, and gymnasium.

A sculpture commissioned by the district was unveiled at the 1961 dedication. Created by artist Henry Rollins, a graduate of Garfield and then a student at the University of Washington, the artwork consisted of three carved figures of cedar. It had been hoped that the sculpture could be made from an old madrona tree that been taken down to make way for the new addition, but when madrona wood proved too hard to carve, cedar was substituted.

B Center

In September 1970, Madrona became B Center (Madrona) and served 5th and 6th graders in Meany-Madrona Middle School. The kindergarten rooms became art and family life rooms. A former play court became the Learning Resources Center. A change in faculty and administrators took place at this time. Desegregation efforts began in 1971, when middle school students from the Wilson, Eckstein, and Hamilton neighborhoods were bused to Meany-Madrona, while students from the Madrona attendance area were transported to one of the north-end schools. A total of 842 students were selected to participate in the first year of the middle school desegregation program. The district aimed to reduce the percentage of African Americans at Meany-Madrona to 25 percent while increasing the percentage at north-end schools to 16 percent.

Parents and staff became concerned that middle schoolers required more growing space. In the March 1978 desegregation plan, the district decided to return the Madrona building to its original function as an elementary school. Beginning in September 1978, Madrona middle schoolers began attending Washington Middle School. As part of the desegregation plan’s magnet program, in 1978 Madrona became home for the elementary program for highly capable students, known as the Individualized Progress Program, or IPP, later known as the Accelerated Progress Program (APP). Most IPP students came by bus from all over the city and shared the building with students in the neighborhood elementary school program. In the first few years of this arrangement, IPP students attended separate classes for reading, social studies, and math while sharing classes in music, art, and physical education. Later the two groups were completely separated. Beginning in 1983 and for the next few years, IPP students in grade 5 went to Washington Middle school, which housed the middle school IPP program.

Expansion to K-8

In September 1997, Madrona’s APP students moved to Lowell, reducing Madrona’s enrollment to 295. Beginning in 1998, 6th grade was added at Madrona, and in 1999 7th grade was added. Expansion to K-8 was completed in the 2000-2001 school year. Meanwhile, the school’s mix of students was changing rapidly. In April 2001, the University of Washington and private donors pledged $1 million to Madrona over a five-year period with a goal of “boosting academic performance in a school that has struggled with low test scores and has been abandoned by many neighborhood parents.”

With Madrona’s buildings aging and in need of upgrades, $13.7 million from a 1995 school levy was used to renovate and expand the historic building. Students attended the former Lincoln High School in the Wallingford neighborhood as their interim site during the 2001-2002 school year while their school was under construction. When the project was completed in the summer of 2002, improvements included the construction of a gym, and the grounds were adorned with a 2-ton metal sculpture of a madrona tree. The 1917 building had been demolished and a new addition for the middle school students that included their own entry was constructed at the south end of the 1961 addition. In 2017, Madrona reverted to an elementary school for grades Kindergarten through 5th grade.

By 2021, Madrona had instituted a Room Parent Program with a goal of increasing the number of family members representing African American males and children of color in school engagement (events, volunteering, homework support) from 20 percent to 60 percent engagement over a three-year period. Each classroom was assigned a room parent who was asked to help foster communication from teachers to families and “to attract families of color for engagement opportunities.”

History

Randell School

Location: 33rd Avenue and E Union Street

Building: 2 rooms in wood barn

1890-91: Opened

1902: Addition

1903: Site expanded to 1.84 acres

1904: Closed

1906: Building sold and removed

Madrona School

Location: 33rd Avenue and

E Union Street

Building: 8-room frame

Architect: James Stephen

Site: 1.84 acres

1904: Opened

1917: Addition (Edgar Blair); site expanded to 2.1 acres

1960: 1904 building demolished; Addition onto 1917 structure (Stoddard & Huggard)

1970: Formed part of Meany-Madrona Middle School

1978: Returned to elementary school use

2000: Renamed Madrona K-8

2001: School closed for construction; Students relocated to Lincoln as interim site

2002: School reopened; Renovation and addition (DLR Group)

2017: Renamed Madrona Elementary School

Madrona Elementary in 2023

Enrollment: 259

Address: 1121 33rd Avenue

Nickname: Panthers

Configuration: K-5

Colors: Black and gold