Chinese immigrants, largely men, began arriving in Seattle in the 1860s, and played a key role in the development of Washington Territory, providing labor for the region's mines and salmon canneries and laying much of the railroad track that connected Washington to the rest of the country. Although initially welcomed, Chinese laborers soon became the target of resentment, especially by white workers, and were targeted in 1882 by the first major restrictions on immigration to the United States. On February 7, 1886, a mob rounded up nearly every Chinese person in Seattle and herded them to the waterfront and a waiting steamer. Civic leaders attempted to prevent the disorderly exodus. Eventually the Chinese were expelled, but not before violence that resulted in at least one death.

Seattle's First Chinese

Historians believe that Seattle's first Chinese resident was Chun Ching Hock (1844-1927), who arrived around 1860. Chun, whose name was sometimes written "Chin Chun Hock," was the vanguard of hundreds of Chinese immigrants lured by the Northwest's "Golden Mountain" and the jobs to be had: digging mines, laying railroad tracks, and canning salmon.

The Northern Pacific Railroad completed tracks from Lake Superior to Tacoma in 1883. Two thirds of the men who laid track for the Western Division of the railroad were Chinese, some 15,000 men across several states. Chinese men also helped to build the Seattle to Newcastle railroad. Initially, Seattle's whites welcomed the aid of Chinese labor, but this attitude soured during the hard times of the 1870s and led to passage of the national Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. The Chinese Exclusion Act was the first significant law restricting immigration in the United States. Chinese immigration to the United States was suspended for 10 years, and Chinese persons were ineligible for naturalization.

Racism at Fever Pitch

White workers, including recent German and Scandinavian immigrants, came to view the low-paid Chinese as unfair competitors for scant jobs during the depression of the mid-1880s. Local organizers of the Knights of Labor and other early unions excoriated them as potential strikebreakers. The anti-Chinese agitation on the West Coast reached fever pitch in 1885-1886, and the Territorial Legislature passed a law barring Chinese ownership of property. Populist agitators demanded the expulsion of the 350 or so Seattle Chinese residents living mostly in the first Chinatown east of the "Lava Beds," Pioneer Square's red-light district. The town's "better elements," led by Judge Thomas Burke (1849-1925) and Mayor Henry Yesler (1810-1892), tried to cool passions, but they also agreed that the Chinese had to go, albeit by orderly and legal means.

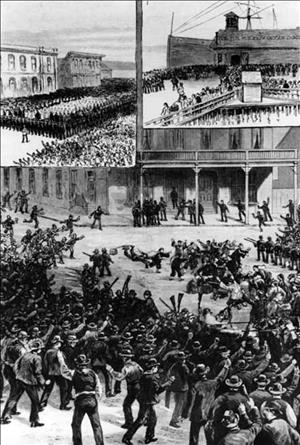

This approach proved too slow for activists such as socialist firebrand Mary Kenworthy and utopianist George Venable Smith, who later founded the Puget Sound Co-Operative Colony at Port Angeles on the Olympic Peninsula. On February 7, 1886, a throng of workers rounded up virtually every Chinese in Seattle and herded them to the Ocean Dock at the foot of Main Street for passage out of town on a waiting steamer. Police and a contingent of the volunteer Home Guard met the mob and its frightened charges at the pier. A stalemate ensued when territorial governor Watson Squire prevented the ship from leaving.

The following morning, nearly 200 Chinese embarked for San Francisco, stranding another 150 on shore to await the next boat, due in six days. When police and deputies tried to escort this group back to their homes, the mob rioted. The deputies fired into the crowd, and five agitators fell. One died of his wounds. In retribution, the mob demanded Judge Burke's neck. Governor Squire and President Grover Cleveland (1837-1908) declared martial law. Passions gradually cooled in Seattle and elsewhere as all but a few Chinese departed. Congress ultimately paid $276,619.15 to the Chinese government in compensation for the West Coast rioting – but the actual victims never saw a dime.