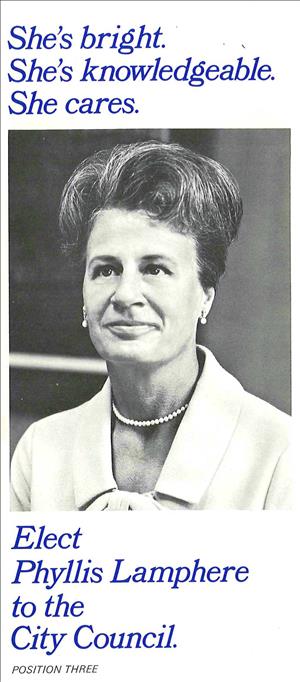

Phyllis Lamphere (1922-2018), a native Seattleite, was deeply involved in the city's civic life for more than 50 years. She served on the city council from 1967 to 1978, where she was instrumental in pushing through multiple reforms and worked on many of the most contentious issues of a contentious era. After an unsuccessful run for mayor in 1977, Lamphere went on to work for the federal government, and she later formed her own public-affairs consulting firm. Among many other achievements, she was a driving force behind the creation of the Washington State Convention & Trade Center and served on its board for more than 20 years. In July and August 2013, Lamphere was interviewed at her apartment in Seattle's Horizon House by HistoryLink.org intern Callan Carow. In these People's Histories, organized by topic, Lamphere recounts some of the important events of her career in politics and public service and provides an inside look at the workings of government and the life of an extraordinary woman. This first segment of the oral history covers her early years, her first involvement in civic affairs, her 1967 election to the Seattle City Council and the fundamental reforms that came during her tenure, and her efforts to address complex problems through cooperation among local governments.

From Old Seattle Stock

I am Phyllis Lamphere. I am a native of Seattle. I come from a long line of generations. My grandfather came out to Seattle to go up to the Gold Rush and subsequently returned with his family. My paternal grandparents were likewise Norwegian and settled first in Minnesota and then came out here. Again, that grandfather also went to the Yukon. So that was a long time back.

Both families were raised in the Seattle area. My father was born in Tacoma, my mother was born in Chicago and came out here at age 5. Both families, mostly my father's family, were very involved in city affairs right from the outset. My grandfather worked in the carpenter's shop for the city when he arrived here, and I have aunts and uncles, on both my mother's and father's sides, who worked for the city. Hence, my deep interest in what happens in Seattle. It's been around me and about me and to me my entire life, so I am deeply committed.

I went to Seattle public schools, graduated from Lincoln High School, and won a scholarship to Barnard College in New York, the women's undergraduate college of Columbia University, and majored in math. When I finished, World War II was on. And so I hastened back to Seattle and went to work for Boeing Aircraft in the war effort. That was in 1943. I married in 1944, in July. My husband was killed in a kamikaze attack on a ship in the Luzon Straits. So I had to face another challenge in life at that point. To shorten this introduction, I went -- after I lost my husband -- to work for IBM, was trained as an assistant service analyst, and eventually came back to Seattle in that capacity. And was married again and raised my family here. But at that point I combined two interests -- one, my deep interest in Seattle and everything that happened, and secondly, my interest in systems, which was what I did for IBM.

Getting Involved in Government

In 1960, jumping forward, or '62, the city commissioned an administrative survey with Booz, Allen & Hamilton, and that survey resulted in a recommendation to change from the weak-mayor system in Seattle to the strong-mayor system. I was active in the League of Women Voters at that point and I convinced the league to take on city government as a study.

We studied it for several years, two years at least, maybe three, doing a basic study of how the city worked, who was involved and so on, and the last year in going over the recommendations of the professional survey and reaching a position in favor of the strong-mayor system. I had done preliminary work on that, I worked on several charter amendments to try to bring some of the independent commissions under the administrative umbrella of the city, and changing the civil-service rules so as to update the way the city could be managed. But the major effort, and the major accomplishment, took two years in doing. I was the organizer and chair of a committee we called the Committee for a Strengthened Seattle Government. It was the League of Women Voters, the Municipal League, and the CPA Society. And I did the major lobbying in Olympia to change the city's budget law.

At that time, there was a law on the books that said any city with a population over 300,000 vested its budget responsibility in the city council. Seattle was the only entity over 300,000, so it was clearly a piece of special legislation to serve the existing power structure in Seattle. It took us two sessions to change that law. It was opposed by the city, the powers that be in the city, but after two years of going down there every day of the session, we finally got enough votes to pass it. That was the act that changed Seattle city government, and I am proud to have been a major part of that.

A Reform Election

I ran for city council in 1967. At that point, two additional reforms had taken place to which I was attached. One, we changed the elections from spring to fall for cities. City elections had been in February and March, and they were changed to September and November. That was one change.

The second change was that we did away with what we called the bid-sheet ballot and said the council members would run by numbered positions. So there would be five running at one time, at one election, four running two years later, and the positions would be numbered to take up all nine. That was significant because you could actually run against a person instead of running against the whole lot. And the latter, the bid-sheet ballot, favored the incumbents because of name familiarity. All you do is write down four that you want, and enough people did that so you could never change anything over. So those two measures were in effect.

There were three of us newcomers who were elected. I was one, Tim Hill was another, and Sam Smith, the first black American [on the council], were elected in that '67 ballot. Two sitting council members were re-elected, Charles Carroll and Myrtle Edwards. But at least three new ones got on. And we began to change things immediately.

Reforming and Restructuring City Government

I have to tell a famous story about this. The government had been so tightly controlled that no one could get anything done, other than what the powers that be wanted. And the powers that be [on the city council] were primarily businessmen, just one woman, from the little neighborhood chambers. That's the way they spread out the influence.

They each had a department or a section of the government that they ran, because they had chaired these significant committees. For instance, the utilities committee was chaired by one councilman, and he actually, for all intents and purposes, controlled the water and the light departments. Similarly, the public safety committee controlled police and fire. The streets and sewers, of all names, controlled transportation and sewage and so on. So they each had their own little territory and they dictated what happened there, which is what we were trying to get away from, because that represented the weak-mayor system -- the mayor did not have the administrative control, he did not have the budget control, and if you don't have the budget control, you can't control the operations. So that was the way it went.

So the law said that the city had to pass its budget by December 1st. We didn't go into office until about the end of November, so we had a very short time to act on this budget, and this was a budget that had been drawn up by the council because the reform had not yet gone into effect. And so we were called to a budget committee meeting, we were in the back conference room out of the view of anybody, and our finance person came in and said, "The budget is all ready and we have 'x' amount left over." I was sitting to the right of the chairman, and he turned to me and said, "Phyllis, what would you like?" I had just been named land-use chair, planning chair, so I just spurted out, "Four planners." And he pounded his gavel.

Then he went on to the next one, which was Tim Hill, and he said, "What would you like, Tim?" Tim was as flabbergasted as I was, and he said, "Detox center." Bang. And he got to Sam: "What would you like, Sam?" And he said, "Youth patrol." We distributed that excess within 10 minutes, and the budget was complete. It was never argued in public, never presented in public. It was finally presented as a fait accompli.

Well that just verified our feeling about closed, controlled government. So the first thing I did, when we were installed, was to introduce an ordinance to set up a legislative-review committee, because with the administrative functions going over to the mayor's office, now we had to figure out how the council should really operate and define its responsibilities, which were representation, legislation, and oversight. So we restructured the whole council. We called their activities for what they were. So a lot of effort was put into restructuring that so the council would be an effective body.

We also changed the rules of operation. We made all the meetings open meetings, had all the hearings in the council chamber -- anyone could testify. We published our agendas in advance. None of this had happened before, so essentially, we installed a really open government. So that's, I think, the major change that has happened to this day in the government in this city, and as I said, I'm very proud to sort of have sort of steered that effort.

In the planning field, we also made a lot of changes, because the decisions in land use had also been handled very -- I wouldn't say clandestinely -- but very partially, and there weren't hearings, the council would meet or talk in their offices and decide whether certain variances should be given or conditional-use permits. But it was not an open and fair and all-inclusive process, so all the way through, that was the way we wanted to move.

Vietnam, Civil Rights, and the Great Society

We also went in at a time when the riots were waging about civil rights and Vietnam, and many other things. It was a time of great disquiet. The neighborhoods had been segregated, and so one of our early acts was to put forward an open-housing ordinance because neighborhoods had been redlined, everybody knew that, but we had to work up to a majority of the council to pass it. We had in Tim, Sam, and me, Charlie Carroll, and Myrtle Edwards, we had a majority. So we passed, but it was bitterly fought, to pass this open-housing ordinance. And I can remember when we finally did because one of the old timers finally swung over and voted with us, and when that happened, another one stormed out of the council chamber and said, "This is the darkest day in Seattle's history." So tensions were high, things were difficult, and so we had that to wade our way through.

It also was a time when the federal government became a partner in city affairs. First through the Model Cities program, and then through federal revenue sharing. And Johnson's Great Society program -- first time that the federal government, except for some transportation grants and special allocations, the first time we got funds that went to social programs. The city had never been involved in social issues. We never had any money for that sort of thing. Now, with the expanded responsibilities given to cities and the expanded funding given to cities, we got in the business of trying to figure out "Well how do we extend social services to the community?"

So we established -- and we had a wonderful director, Walt Hundley -- who was a Model Cities administrator. And they set up community clinics, and all kinds of housing, and community centers, and health centers, Meals on Wheels programs, all that sort of thing, bringing those critical programs to the community to supplement what the city could do through its regular responsibilities. So that was a big transformation, a big responsibility to try to figure out how that partnership would work. What was the state's role, what was the city's role, and so on. So those were the sorts of things that commanded our early attention.

Culture and Corruption

Later on, we got into some of the cultural issues, some of the things like historic preservation, support for the arts, pea patches, Bumbershoot, that kind of thing, that were enrichments that had never, ever been offered because through the city's expanded station and responsibilities and resources, we could begin to introduce some of those enriching experiences and opportunities.

We also lived through the Boeing layoffs in the '70s. We also lived through a police scandal, gambling scandal, where the police chief had to resign. And that was part of that old system. The police chief, the police, had been operating in their own private way, licenses had been distributed in their own preferential way. The license chairman could decide who got a license, who got a cab medallion. In a lot of ways, those things were totally decided by a single person on the city council. So that was really a huge transition toward openness, toward fairness, toward inclusiveness that we benefit from still today.

Regional Cooperation

My second effort on the city council was to convince the council to set up an intergovernmental-relations committee, and I became chair of that. The reason for that was because we were more and more becoming involved with other governmental entities on decisions in programs we shared. All the [city] council was on the Metro council right from the beginning, and I was finance chair for Metro. But we also became more and more involved in our neighboring counties, Kitsap, Pierce, and Snohomish, in what was originally called the Puget Sound Council of Governments.

That entity did not have much, it was more or less a volunteer operation, until the federal government designated that agency as a federal clearinghouse for funds, for planning, and for transportation for the four-county region. That was a big responsibility. So then we got serious about how we should make those priorities, how we should distribute those monies, and it became much more relevant and the decisions obviously pretty contentious for a while -- when you set priorities between two jurisdictions about how money is going to be distributed, it gets very contentious.

So we set that up, but at some point King County decided they weren't getting a fair shake, and they were threatening to pull out of the conference. So I proposed that we set up sub-regional councils, one for each of the counties. They can have their own priorities then and their own sort of weighted vote, and their own say, 'cause King County obviously had a central city and 28 small cities at that point, and the county, so they felt they should all have a way of being represented. So that was finally set up. I chaired the King County Regional Council and things smoothed off, and we kept the regional council together. Which was a good thing, because it's still in place now, has been renamed several times, but it's important for that relationship with the federal government.

I also was involved in setting up the health-services entity, which was all of the counties west of the Cascades. I was also vice-chair of the state law and justice committee. The attorney general was the chair, I was the vice-chair. We apportioned grants from the federal government for law and justice, and apportioned those throughout the state. So I got pretty deep into criminal justice at that point, and was still on that when I left the council. I also helped to negotiate the transfer of the Pacific Science Center from the federal government to the nonprofit that now runs it, the Pacific Science Center Foundation. So that was another one.

To go to Part 2, click "Next Feature."