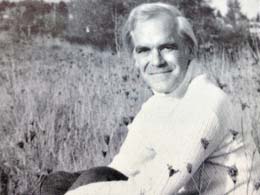

In September 1954, David Wagoner (b. 1926), who will become known as the dean of Northwest poetry, drives his 1950 Chevy coupe from Indiana to Seattle to assume a position teaching at the University of Washington. He has been summoned by his mentor, the legendary Theodore Roethke (1908-1963). Accustomed as Wagoner is to modest Appalachian ridges, the grandeur of the Rockies and the Cascades strike him as excessive. But descending into the lush green atmosphere of his new home, he experiences a sense of awe and promise of healing that will distinguish the most beloved and anthologized poems in what will become his large, frequently honored body of work.

Changing Working Habits

Wagoner, who had studied poetry with Roethke while a student at Penn State, was 28 when he arrived in Seattle. He'd been teaching for four years when Roethke told him of his University of Washington job offer, and had already embarked on a promising literary career, with a novel and book of poems about to be published. But Wagoner's creative process altered after he settled in amongst Roethke's poetic tribe, which included other former students making names for themselves -- Richard Hugo (1923-1982), Carolyn Kizer (1924-2014), and James Wright (1927-1980).

"I changed my working habits," he recalled. "I began working more freely. I spent more time in revision, and more time than ever before in the evolving of the raw material for a poem. I discovered ways to get at my unconscious mind in ways I had never been able to before. In writing a poem I had tried simultaneously to be the dreamer, the explorer, the poet and the critic -- all at once. As soon as I divided those into three stages, everything changed. I allowed myself to be crazy and very free in working, and then tried to make a poem out of the raw materials, and then criticized the poem after that. Roethke set me an example there. I don't know if I would have done it so soon if he hadn't done what he did" (O'Connell, 54, 55).

Changing Place

There were more revelations after Wagoner ventured out into the Olympic Peninsula wilderness. "I thought I'd found where God lived," he wrote. "But the god waiting for me in that tangle of moss, wildflowers, nurse logs, swordfern, and huckleberry turned out to be Pan. I became disoriented in something under ten minutes and spent the next hour relocating my car. By the time I did, I was no longer a Midwesterner. I didn't know what I was, but I was certain I'd been more or less lost all my life without knowing it. It was the beginning of my determination not to be lost in any of the woods, literal or figurative, I might explore after that" (Contemporary Authors Autobiography Series, 406).

It was also the beginning of what one critic called "the first book of poetry to reflect his relocation physically, aesthetically and emotionally; the Midwest is abandoned for the lush abundance of the Pacific Northwest, and Wagoner's style is less concerned with lamentation or complaint and more with cataloguing all the bounty around him" (Poetry Foundation). This book, The Nesting Ground, was published in 1963, the same year Roethke died of a coronary occlusion at the age of 55.

Furthering the Legacy

Wagoner took over Roethke's classes and in other ways furthered his mentor's legacy. He wrote a play based on Roethke's inspirational teaching methods and saw it produced at Seattle's ACT Theatre. Along with many novels and books of poems, Wagoner published a book, Straw for the Fire, based on a selection and compilation of a massive collection of Roethke's notebooks.

For 30 years Wagoner served as editor of Poetry Northwest, the prominent journal founded by Carolyn Kizer. After his segue into professor emeritus status at age 75, he continued to publish new work as well as teach poetry workshops and master classes throughout the Northwest and beyond.