Sammamish (King County) is located on a broad plateau about 14 air miles east of Seattle. Until the 1870s, the area was largely uninhabited by humans. In 1877 Martin Monohon became the first permanent non-Indian settler on the Sammamish Plateau, but for much of the next century the region was mostly woods, chicken farms, dairy farms, and lake resorts. Development began edging onto the plateau in the 1960s and accelerated in the final decades of the twentieth century, transforming the pleasant countryside into an affluent Seattle suburb. The city of Sammamish incorporated on August 31, 1999, and in recent years has twice been recognized by Money magazine as one of the best small towns in America to live in. The 2010 U.S. Census recorded Sammamish's population as 45,780 and its land area as 18.2 square miles.

Beginnings

Sammamish is a Snoqualmie name. According to members of the Snoqualmie Tribe, the name is a corruption of two words: "Sqawx," the Snoqualmie name for Lake Sammamish, and "abs," a suffix which refers to people of a certain area. The city is bordered by Lake Sammamish on its west, and it and the surrounding plateau are home to a number of small lakes. Though Sammamish is only 14 air miles from Seattle, the driving distance is considerably farther at 21 miles because you have to loop around Lake Sammamish to get to the city.

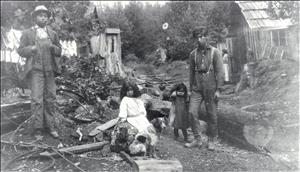

In pre-settlement history (and for many years after) the land that makes up Sammamish was forested with Douglas fir and cedar trees. Members of the Snoqualmie Tribe hunted on the plateau, but the main tribal grounds and villages were farther east. However, there was a small Snoqualmie village with perhaps several dozen residents at the foot of Inglewood Hill near Lake Sammamish in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Many of these Native Americans left in the early 1900s. A few remained and gradually assimilated into the community of Inglewood, which informally encompassed what is today (2013) the northern half of Sammamish.

Monohon

Martin Monohon (1820-1914) is considered to be the plateau's first permanent non-Indian settler. A strong, adventurous outdoorsman, Monohon settled on the plateau in 1877. He built a log house east of the present-day intersection of SE 24th Way and E Lake Sammamish Parkway on 160 acres that's now in the Brookemont subdivision and the northern part of the Rockmeadow Farm subdivision. During the 1880s he maintained a ferry landing on the lake aptly named Monohon’s Landing, located near today's SE 32nd Street. In October 1887 he drafted a petition to build one of the earliest roads up onto the plateau, which was officially named Martin Monohon Road (but became known as Monohon Hill Road). Part of this road is now SE 24th Way. Monohon Hill (now Waverly Hills) was named after Monohon and so was the town of Monohon.

The catalyst for the town's formation came in 1889, when the Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern Railroad Company completed a track along the eastern shore of Lake Sammamish. The Donnelly Mill moved from the town of Donnelly on the southwestern shore of the lake to Monohon, and a new company was established to run it. The new company was named the Allen and Nelson Mill Company, and the mill, which began operation in Monohon in November 1889, became the town's anchor for the next 36 years.

In 1906 the company was sold to C. P. Bratnober (1866-1928), John E. Bratnober (1879-1951), and C. S. LaForge. John Bratnober, a preeminent player in the plateau's timber industry for most of the first half of the twentieth century, expanded the mill's operations and the town of Monohon grew along with it. By 1911 the town had a population of 300, its own water system, a railroad depot, and a 20-room hotel.

It all came to a spectacular end on June 26, 1925, when nearly the entire town burned down in a fire that was caused by a carelessly flipped cigarette butt that landed in a pile of sawdust. The town never came back, though the mill was rebuilt and soldiered on in various incarnations until 1980. The only remaining traces of Monohon are a few early twentieth-century Allen and Nelson Mill homes that were not burned in the fire.

Inglewood

Inglewood, located just north of Monohon, was an informal community that stretched north along the lake from today's SE 8th Street past Weber Point on the northeastern shore of the lake, and east to at least 244th Avenue NE. A relatively small but thriving and diverse community sprang up there between 1890 and 1910. A glimpse from the 1910 census shows how diverse: More than 30 percent of Inglewood's 185 "non-Indian" inhabitants reported they had been born in countries other than the United States; two-thirds of those came from the Scandinavian countries of Sweden, Norway, and Finland. (Forty-five Indians were also recorded in the 1910 census, representing 20 percent of the community's population.) Most of the men (and some of their sons) worked at either the Lake Sammamish Shingle Mill at Weber Point or at a logging camp in the area.

There were lots of children in early Inglewood, and there was a school there for them. The Inglewood Grammar School was built in the first half of the 1890s and operated until 1920. It was located on the southeastern corner of NE 8th Street and 228th Avenue NE, near where the Sammamish 76 service station is now (2013). Originally a simple log building, by 1900 the school had been replaced by a more substantial structure. The school was a traditional one-room school, complete with cloakroom and porch in the newer building. One teacher taught students from first through eighth grades, and the students were seated in rows according to their grade. The building survived for more than half a century after the school closed before finally collapsing from neglect in the mid-1970s.

The First Sammamish

There was a Sammamish before the Sammamish we know now. The first Sammamish slowly developed around 1900 on Weber Point. There wasn't really a town by this name -- it was actually a part of the Inglewood community. But most of its 50 or so residents who lived there during the 1910s considered themselves residents of "Sammamish," and it had a stop on the rail line, two operating shingle mills, and a building that was a bunkhouse, cookhouse, company store, and office all in one to serve the mills.

The first shingle mill, owned by the Lake Sammamish Lumber and Shingle Company, commenced operations in 1892 or 1893 and got off to a fast start. In 1893, it produced more than seven million shingles. It operated for several years before burning down. In 1901, Joseph Weber (1865?-1937) rebuilt the mill and named it the Lake Sammamish Shingle Company. The first mill was located at the tip of Weber Point, but by 1907 Weber had built a second mill slightly farther inland. The mills produced up to 100,000 shingles (primarily cedar) daily, and thrived through most of the 1910s.

The first mill closed shortly after 1915, but the second mill and the small community of Sammamish carried on through the 1920s. However, their days were numbered. By 1930, most of the trees near the eastern shore of Lake Sammamish had been logged. Logging operations were shifting farther east, to Beaver Lake and beyond. Work at the mill slowed, exacerbated by the effects of the Great Depression then underway. Weber closed his company in December 1930, and later in the decade he sold his land and moved to Seattle. Many of the area's residents also moved during the 1930s, and by the end of the decade the first Sammamish was gone.

The Resorts

Sammamish was home to no fewer than four resorts during the early and middle decades of the twentieth century. "Resorts" in those years meant something entirely different from what they mean in the twenty-first century. Typically the resorts consisted of quiet cabins and a lake that provided plenty of aquatic activities, and all of them had a dance floor that was sure to please. In their heyday they were a welcome retreat both for locals and visitors.

Alexander's Beach Resort was located on the southeastern shore of Lake Sammamish, just north of the southern boundary of today's Sammamish city limits. Caroline Alexander opened a small picnic area there in 1917 and operated it until her 1932 death. Her daughter Hazel Alexander Ek (1897-1982) and son-in-law George Ek (1890-1967) took over and expanded it into a mecca that became a favorite for company picnics, private picnics, and picnics hosted by political parties. The resort had a dance hall with a stage and a large open-air pavilion with a huge 20-foot-by-6-foot oven and four 40-foot-long tables capable of seating hundreds. The Eks sold the property in 1966 but the resort remained in operation until 1985, when it was sold yet again. The new buyer razed the structures and turned the property into the Alexander's on the Lake development.

The Tanska Auto Camp was on the southwestern shore of Pine Lake in southern Sammamish. About 1912, John Tanska (1869-1940) bought 40 acres there and spent several years clearing the land. By 1918, a small auto camp was open on the southern half of his acreage. The camp itself was just a field where people pitched their tents and enjoyed the great outdoors, but Tanska also took over 10 cabins on the site that had been left over from an earlier logging operation and rented those out to visitors. The cabins were located near the current (2013) intersection of 216th Avenue SE and SE 24th Street, and some still survive as remodeled houses. The auto camp had a small dance floor and it also sported a popular Finnish sauna. It closed in 1940, shortly after John Tanska's death.

Pine Lake Resort was situated on the eastern shore of Pine Lake, an easy boat ride from the Tanska Auto Camp. The 18-acre resort opened about 1917 with five small cabins but languished until the late 1930s, when owner Reiff French dramatically expanded it. He renamed the resort French's LaPine Resort, but the name didn't catch on. It was "Pine Lake Resort" to some, "Frenchy's" to others. French eventually built 15 cabins (16 if you count his), a small grocery store, and a dance hall that was a favorite with square dancers. Like Alexander's, Pine Lake Resort also was a favorite for picnickers. It operated until 1966, when King County bought the property and converted it into what's now (2013) Pine Lake Park.

The Four Seasons Resort opened on Beaver Lake (roughly a mile and a half east of Pine Lake) about 1936. Owners Gus and Lulu Bartel had 15 cabins built on the property as well as a small lodge and a dance hall. Musician Quincy Jones (b. 1933), who lived in Seattle at the time, played for at least one dance there, about 1949. In 1950, Dick "Andy" Anderson (1912-1968) and his wife, Ruth (b. 1909), bought the 85-acre resort and renamed it Andy's Beaver Lake Resort. They ran it through the 1960 summer season, and then sold the property to the Catholic Youth Organization (CYO). The CYO operated a youth camp (Camp Cabrini) there until 1985, when King County bought the land. Today (2013), it's known as Beaver Lake Park.

The resort at Beaver Lake has another claim to fame. In 1939, the Red Cross Aquatic School held the first of its training schools there. Ten-day classes were held there most years between 1939 and 1956, but it's the 1953 class that stands out: Clint Eastwood (b. 1930) taught lifeguard training classes there that summer. The school offered classes in first aid and water safety, and Eastwood evidently taught both. Two pictures of him hard at work appear in the June 27, 1953, issue of The Seattle Times. He wasn't famous yet -- his acting career didn't start until a few years later -- but he was catching the photographer's eye even then.

Chickens, Mink, and the High Lonesome Ranch

There was more on the Sammamish Plateau during those years. There were dairy farms, chicken farms, and even a small mink farm for a few years. One chicken farm in particular was well known. In 1914, C. J. Sween (1878-1972) bought a 20-acre farm just southwest of today's intersection of SE 4th Street and 228th Avenue SE. Sween (pronounced "Swinn") was going to take up dairy farming until he realized that most of his land wasn't suitable for cattle. Almost on a lark, he took up chicken farming.

His timing was perfect. The poultry industry in Washington was nearly non-existent in 1914, but that changed dramatically over the next 15 years. Sween had come in on the ground floor, and by the late 1920s he was making $35,000 a year (approximately $480,000 in 2013 terms). He grew his farm accordingly and by 1940 he had 300 acres stocked with several dozen chicken coops and thousands of chickens. That year his son, William "Bill" Sween (1913-2000) and Bill's wife, Faye (1916-2011), took over operations at the farm. They began raising fryer chickens (C. J. Sween had centered his operations on egg-laying chickens) and dramatically increased their operations, so much so that at one point in the 1950s Sween's Poultry Farm was the largest fryer grower in the state, processing half a million chickens every year. The Sweens retired in 1965.

By the time the Sweens closed their farm, the High Lonesome Ranch was in full swing a couple of miles away. In 1960 Chris Klineburger (b. 1927) bought 50 acres along and just east of 244th Avenue NE, about a quarter mile south of NE 8th Street, which included a small parcel on Allen Lake. In the next year or so he built a "frontier town" to provide people with a taste of the West. Frontier Town and the ranch consisted of the Lavender Horse Saloon, a bunkhouse, a working blacksmith shop, a smokehouse, a meat processing area (Klineburger kept exotic animals and sold their meat to area restaurants), and lots of horses. In 1965, he established the High Lonesome Riders club at his ranch. The club offered all kinds of pack trips and trail rides to its riders that were tailored to their skills, including long and challenging rides. A year after its inception, the club had 99 members and 120 horses.

During these years, Klineburger and his brothers Gene (b. 1920) and Bert (b. 1926) operated a well-known taxidermy studio (Jonas Brothers, now Klineburger Taxidermy) in Seattle, and also booked hunting trips worldwide. Their clients included Roy Rogers (1911-1998), astronaut Wally Schirra (1923-2007), and Texas politician John Connally (1917-1993). They all visited the ranch (Roy Rogers was a regular), along with guests from as far away as the Soviet Union and China. The ranch thrived into the 1970s, but by the 1980s its heyday had passed. Klineburger leased the property and horse rentals continued there until the late 1990s. But when he sold the land in 2000 Frontier Town was quickly torn down.

Suburban Sammamish

The first modern development in Sammamish, Sunny Hills, edged onto the southern end of the Sammamish Plateau in the early 1960s, featuring acre-plus lots and up. (One resident bought a one-and-a-quarter acre lot in Sunny Hills in 1965 for $3,600, which equates to about $26,700 in 2013.) Sunny Hills Elementary, the first modern school on the southern end of the plateau, opened in 1962. On the northern end of the plateau, the first 18 holes of the 27-hole Sahalee (Chinook for "high heavenly ground") golf course opened in August 1969. A nearby development with the same name soon followed. Sahalee's golf course has been frequently ranked among the nation's top 100 courses in the country by Golf Digest. It also hosted its first PGA championship in 1998.

Still, the plateau was far more rural than urban as the 1960s ended; in 1969, its population was fewer than 5,000. Part of the reason was that there was no easy way to get onto the plateau's northern end. In 1969 228th Avenue NE ended at Inglewood Hill Road, but with the exception of the new golf course, there wasn't much north of Inglewood Hill Road anyway. However, the opening of the golf course and development at Sahalee spurred the northward extension of 228th NE during the 1970s. In 1979 Sahalee Way opened, helping pave the way for development of the plateau's northern end. The first modern school on the northern end of the plateau, Margaret Mead Elementary, likewise opened in 1979. This was followed by more new developments near the school during the 1980s.

About 1984 the plateau's population passed 10,000, but that would triple in the next 15 years. Sammamish's first shopping center, the Sammamish Highlands Shopping Center, opened at NE 8th Street and 228th Avenue NE early in 1985, and a second shopping center, Pine Lake Village, opened several miles to the south in 1989. But as the 1980s rolled on, residents became increasingly concerned with the rapid urbanization (some long-time residents simply moved away in disgust). They felt that the community's needs would be better served by either annexing with Issaquah or Redmond or forming a whole new city.

Incorporation

In those days, the area that later became Sammamish was unincorporated King County. Residents of the northern end of the plateau (north of SE 8th Street) informally considered themselves part of Redmond, and their homes had Redmond phone numbers and zip codes. Residents south of SE 8th had Issaquah phone numbers and zip codes and felt connected to Issaquah. Thus the first serious steps considered were annexation. In 1991 local voters rejected a proposition to annex the southern half of the plateau to Issaquah. That same year Redmond included the northern half of the plateau in a long-range annexation plan, but this was hotly contested and the idea was eventually abandoned.

In 1992, plateau residents rejected Sammamish's first incorporation bid by a wide margin: 58 to 42 percent. Incorporation backers were surprised by the breadth of the defeat and the drive to incorporate cooled. This lasted for only a few years. Residents felt neglected by King County, but they weren't interested in annexing with Redmond or Issaquah. By 1997, incorporation was again was a hot-button topic. Sentiment was more favorable by then, and in 1998 voters approved incorporation with a resounding 63 percent in favor.

There was considerable debate about what to name the new city. Monohon, Inglewood, Sahalee, and even Heaven were bandied about. Sammamish prevailed, and the city formally incorporated on August 31, 1999. The new municipality found itself with plenty of challenges ahead. Its city hall was located in the Sammamish Highlands Shopping Center, there was no post office (and nearly 15 years later, still isn't), and much of 228th Avenue, the main route through the new city, was little changed from the bucolic country lane it had been 50 years earlier. But blessed with an educated and affluent population base, Sammamish proved itself up to the task.

Sammamish in the Twenty-First Century

Sammamish's first city council saw that growth on the plateau during the 1990s had been so rapid that the infrastructure needed to sustain this growth hadn't been able to keep up. The council passed a moratorium on new subdivisions to give this infrastructure time to be built. The moratorium lasted for seven years, and the plan worked. Between 2001 and 2005, 228th Avenue was widened from two to four lanes between the Pine Lake and Sammamish Highlands shopping centers. In August 2006, a new city hall opened at the new Sammamish Commons, and in January 2010 a new library opened next to the city hall.

Sammamish began the 2010s considerably more prepared to deal with growth than it had been a decade earlier. This was a good thing, because the city's rapid growth continued during the early years of the twenty-first century. Sammamish's first census in 2000, less than a year after incorporation, counted 34,104 residents, but in 2012 the U.S. Census estimated the city's population at 49,069, representing an average increase of more than 1,000 people a year since the turn of the century. It's a well-educated and affluent community: Nearly 70 percent of Sammamish residents reported having a bachelor's degree or higher during the period 2007-2011, compared with 45 percent for King County; the city's median household income during that same period was $135,432, nearly double the median of $70,567 for King County.

Sammamish can't be described as conservative, but it leans to the right of the rest of King County. For example, in the 2012 general election Republican gubernatorial candidate Rob McKenna (b. 1962) carried the city by a comfortable margin, despite losing in both the county and the state to Democrat Jay Inslee (b. 1951). Other state and national Democratic candidates on the ballot that year generally fared better in Sammamish, though they didn't carry the city by as wide margins as they did in King County as a whole. Sammamish also supported the two big issues of the 2012 election in Washington state, gay marriage and legal recreational marijuana for adults, though again by smaller margins than in the rest of King County. (Since then, Sammamish's city council has imposed a temporary ban on licensing any recreational marijuana facilities in the city.)

Sammamish is a pleasant city, one where it's not uncommon to see deer strolling through neighborhoods; it feels much farther from Seattle than it is. This attractiveness has not gone unnoticed. Money magazine ranked Sammamish the 12th best place to live in the United States in its annual review of the country's best small towns (population under 50,000) in 2009, and ranked Sammamish 15th in the same survey in 2011. In 2013 Coldwell Banker Real Estate declared Sammamish to be fourth in its list of the country's "top booming suburbs," citing the city's affluence and amenities such as a local symphony orchestra and three private golf courses. The city also offers many community events throughout the year that give its citizens a chance to get together.

Sammamish's transformation from rural retreat to suburban paradise has been so complete that little remains of its original history, with a few exceptions. One is the Bengston cabin, a pioneer cabin dating from about 1888, found in the northeastern corner of Sammamish on 244th Ave NE. The cabin is showing its age, but another exception has a more hopeful future. The Reard House, built in 1895, is presently being restored by members of the Sammamish Heritage Society. Recently moved from its original location at 1807 212th Avenue SE to its new home at Big Rock Park (just north of Pine Lake), the house is full of stories of everyday life on the plateau in decades past that are worth remembering even as Sammamish eagerly embraces the twenty-first century.