On May 5, 1945, Elsie Winters Mitchell (1919-1945) of Port Angeles and five children from the Bly, Oregon, church that her husband pastors become the only civilians killed in an enemy attack on the United States mainland during World War II. They die in the explosion of a balloon bomb from Japan that they discover on Gearhart Mountain in south central Oregon. Balloon bombs have been floated to the United States from Japan in the jet stream since the previous November, and have become a serious concern for the military in Washington and other western states. However, the bombs cause no forest fires or other serious damage, and the six Gearhart Mountain victims will be the only balloon-bomb casualties.

Elsie Winters Mitchell

Elsie (or Elyse) Winters was born in Port Angeles, Clallam County. Her father, Oscar H. Winters (1879-1952), worked at the R. M. Morgan sawmill and did carpentry. Her mother, Fanny E. Winters (1887-1968), maintained the home and raised the children. Following her high school graduation, Elsie Winters went to Seattle and worked as a maid for the family of the noted Seattle libel law attorney Paul Ashley (1896-1979).

In 1941 she enrolled in the Simpson Bible Institute of Seattle, the western regional bible school for the Christian and Missionary Alliance Church. Here she met fellow student Archie Emerson Mitchell (1918-1969?), who came to the school from Ellensburg. Following graduation, Elsie and Archie married in Port Angeles on August 28, 1943. Their honeymoon was a trip across the country to Nyack, New York, where they attended a one-year program in missionary work.

The couple returned to the Northwest, and in March 1945 Archie Mitchell became the pastor at the Christian and Missionary Alliance Church in Bly, Oregon. The Bly church was to be the Mitchells' two-year "home service" before their overseas missionary work. Bly was a town of about 450 people located between Klamath Falls and Lakeview in south central Oregon. In May 1945 Elsie was five months pregnant and the couple was excited to start a family. On May 5, 1945, Reverend Mitchell and his wife took a group of five children from the church to nearby Gearhart Mountain for a picnic.

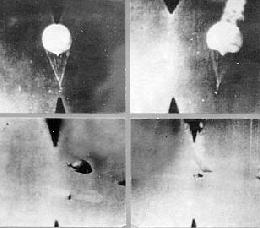

Balloon Bomb Explosion

May 5th was a beautiful spring day. The Mitchells took the children to Leonard Creek on Gearhart Mountain. Reverend Mitchell drove the group to the picnic area. He let his wife and the five children out of the car to walk through the woods to a picnic site as he located a good parking spot. He parked and was coming through the woods as Elsie Mitchell called out that they had found something interesting. Apparently they tugged at the object.

A powerful explosion killed Elsie Mitchell, Sherman Shoemaker (1934-1945), Edward Engen (1931-1945), Jay Gifford (1932-1945), Joan Patzke (1931-1945), and Dick "Joe" Patzke (1930-1945). Within moments Archie Mitchell was at the blast location and found his wife on fire. He put out the flames and saw the children's mangled bodies.

That afternoon an ordnance expert from Lakeview Naval Air Station arrived to remove any remaining explosives. Also, Lieutenant Colonel Charles F. Bisenius (1900-1973), an intelligence officer, came from Fort Lewis in Pierce County, Washington, to secure the site. He directed that newspaper accounts identify the blast as an explosion of an unknown source. The balloon bombs received the silent treatment so that the Japanese military would believe that they had not reached the United States or caused any damage.

Archie Mitchell accompanied his wife's body to Port Angeles for her funeral and burial. She was buried in the city's Ocean View Cemetery, where a monument recalling the tragedy was erected. On May 9, a mass funeral for four of the children was held in Klamath Falls with 450 people attending. The body of one victim, Sherman Shoemaker, was sent to Live Oak, California, for a funeral and burial in a family plot.

Balloon Bombs from Japan

The Japanese military's balloon-bomb or fire-bomb weapon utilized hydrogen balloons carrying incendiary and antipersonnel bombs. The program was designed to send inexpensive weapons to traverse the Pacific Ocean via the jet stream and strike North America. The plan was for bombs to explode in West Coast forests and start fires, kill people, and cause damage and panic. Japanese military officials expected the program to bring the war to North America. The balloon bombs, called "fugo" or wind ships, had a sophisticated yet economical design. The balloon was made of layers of mulberry paper. Shroud lines on the gas-filled balloon held the bomb assembly that carried anti-personnel bombs and incendiary bombs. An automatic altitude-control device kept the balloon at the proper altitude to stay in the jet stream.

The first of nearly 10,000 balloon bombs was launched on November 3, 1944. On November 5, the first balloon sighting in the United States occurred southwest of San Pedro, California. That was an experimental balloon that had been launched earlier and did not carry a bomb. Approximately 400 balloon devices were found or observed in North America. With the early discoveries, some Americans feared that the devices might be used to deliver bacteriological or chemical warfare or both. The first balloon bombs that were found were tested and found free of these agents. That did not rule out future chemical attacks.

In January 1945 the United States Office of Censorship instructed the press not to report any bombs found. Silence would deny Japanese officials cause to consider the program effective. This press silence seemed to work, as the Japanese did not learn of landings. The program was canceled in April 1945. In the United States, press censorship was ended on May 22, 1945, following the Gearhart Mountain explosion. Getting the word out to others who might find balloon bombs to leave them alone was deemed critical.

Balloon bombs were recorded 28 times in Washington and some of those incidents generated military concern. On March 10, 1945, a balloon bomb hit a power line at Bonneville Dam on the Columbia River and a power outage followed at the Hanford Engineer Works, which was producing plutonium for atomic bombs. Another balloon bomb fell in Everett not far from the Boeing B-29 plant there. Protection of essential Washington infrastructure, such as Boeing plants and Hanford, assumed great importance.

The army responded with the Sunset Project, a radar and fighter effort to intercept the balloons and shoot them down. On May 1, 1945, the project became operational with an early warning radar system installed with two radars in the Seattle area and one at Paine Field in Everett. Additionally, civilian observers from the Ground Observer Corps, who watched the sky for enemy aircraft, were instructed to observe and report other objects as well. Fighter aircraft were assigned to Paine Field in Everett and other bases to intercept identified targets. However, by the time the Sunset Project started the aerial threat had ended, although balloon bombs continued to be found on the ground. Sunset Project aircraft did respond to alerts that proved to be weather balloons or coastal blimp patrols.

Another military response was Operation Firefly, which used specially trained army firefighters, the African American 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion, to fight fires caused by balloon bombs. The 555th arrived in the Northwest in April 1945 and was stationed at Pendleton Field near Pendleton, Oregon. While the balloon bombs did not start any fires, the "Triple Nickels," as the 555th firefighters were known, made 1,200 jumps to fight 36 forest fires. They earned a second nickname, the "Smoke Jumpers."

Archie and Betty Mitchell

On June 1, 1947, Archie Mitchell married church member and recent Simpson Bible Institute graduate Betty Patzke (b. 1921), who was the older sister of two of the bomb victims. Adding to her grief was the loss of another brother, Technical Sergeant Jack Patzke (1924-1945), who was killed in Europe. He was captured when the bomber on which he was a crewmember was shot down over Germany on April 30, 1944. Jack Patzke was killed by his captors almost one year later. His remains were returned to the United States and buried in the Linkville Cemetery in Klamath Falls, Oregon. His brother and sister killed in the bomb explosion were also buried there.

Archie and Betty Mitchell left for Vietnam on December 23, 1947, for two terms of missionary service to the people of Da Lat. A third term assignment was to the Ban Me Thout Leprosarium in Darlack Province, South Vietnam. The leprosarium was financed by the Christian and Missionary Alliance, the Mennonite Central Committee, and American Leprosy Mission, Incorporated.

Seventeen years after the World War II tragedy, the Mitchells again became victims of war. On May 30, 1962, a force of 12 Viet Cong took Archie and two other staff prisoner. The remainder of the staff was left behind, including Betty and the four Mitchell children, who lived at the camp.

While a prisoner Reverend Mitchell was occasionally allowed letter contact with his family, with the last contact coming in 1969. The United States military launched two raids to free the captives, but in both cases the captives had been moved before the raids. Archie Mitchell was not heard from after 1969 and his name was not on prisoner lists at the end of the war, so he was presumed to have died. Betty Mitchell continued missionary work in Vietnam. She was also taken captive, in 1975, but released after six months. She returned to missionary work at the Dalat school in Penang, Malaysia. She retired in 1987 to live in North Carolina and work with Vietnamese refugees.

Remembering the Victims

Weyerhaeuser Timber Company's Eastern Oregon Division constructed a monument at the explosion site in 1950 as a memorial to the six killed there. Elsie Mitchell's mother and father attended the August 20, 1950, dedication. The monument is native stone with a bronze plaque listing the victims' names followed by the statement "Who Died Here, May 5, 1945, By Japanese Bomb Explosion, Only Place on the American Continent Where Death Resulted from Enemy Action During WW II." The monument was transferred to the Fremont-Wimena National Forest in 1998 and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2003. The site, 13 miles northeast of Bly, is now part of the Mitchell Recreation Area and maintained by the United States Forest Service.

The Mitchell Recreation Area and monument has received a number of Japanese military veterans and civilians apologizing for the deaths. In 1976 Sakyo Adachi (1905 - ?), a Japanese meteorologist who helped design the balloon bombs, placed a wreath at the monument. Japanese students sent six cherry trees with their condolences. A rededication ceremony in 1995 noted the peace gestures and dedicated the cherry trees. At the monument site is a ponderosa pine that still shows the shrapnel scars from the explosion and removal of shrapnel. Named the "Shrapnel Tree," it is an Oregon Heritage Tree. A plaque near the tree relates its story. The monument site is open to visitors from mid-May to October.