Chief Seattle's parents were from tribes on both sides of Elliott Bay and the Duwamish River. He lived during a time of change for his people and the Puget Sound region. He welcomed the Collins and Denny parties when they arrived as the first pioneer families in the Seattle area. Chief Seattle was considered a peacekeeper between the settlers and his people. He was respected so much that the new city was named in his honor. (This essay was written for third and fourth grade students who are studying Washington State History and for all beginning readers who want to learn more about Washington. It is one of the HistoryLink Elementary set of essays, all based on existing HistoryLink essays.)

si?al

Chief Seattle was born on the Kitsap peninsula sometime in the 1780s. His father’s name was Schweabe; he was a member of the Suquamish Tribe. His mother’s name was Scholitza; she was a member of the Duwamish Tribe. When Seattle was old enough to receive an adult name, he was called si?al.

This name is difficult to say in the English language. Saying "Sealth" (rhyming with "wealth") is not correct. The correct Lushootseed pronunciation has two syllables. There is no "th" sound in that language. So "Seattle" is closer to how it should be pronounced. Skagit tribe elder Vi Hilbert worked very hard to preserve the Lushootseed language. She was afraid that the language would be lost. Recordings of her saying common words in Lushootseed can be heard on HistoryLink.org. One of the words that she says is the name "Seattle." She pronounces it "See-ahlsh."

Chief Seattle lived in a time of change for his people and the Puget Sound region. Stories passed down through generations of the First People say that Seattle was a small boy when Captain George Vancouver’s ship entered Puget Sound. Canoes filled with local Native Americans paddled out to view the grand sailing ship Discovery. In one of the canoes was young si?al.

Written records from Fort Nisqually show that the young Seattle traveled there to trade beaver and sea otter furs. He wanted sheep-wool blankets in exchange. He admired and showed respect for white leaders and businessmen.

As he grew up, his people realized that he had what it took to be a good leader. His parents were from tribes on both sides of Elliott Bay and the Duwamish River. His actions proved that he was both smart and brave. One story tells of a group of warriors who were coming down the White River to attack the Suquamish Tribe. Seattle had a large tree cut down at a bend in the river. When the enemy canoes came around the corner, they crashed into the tree. The warriors fell into the water and could not escape from Seattle’s men on the shore.

By the time that the settlers began arriving, Seattle had been accepted as chief by most Native Americans in this area. He also became a "firm friend of the whites." He was baptized by Catholic missionaries as "Noah." He welcomed the Collins and Denny parties when they arrived as the first pioneer families to this area. He was considered a peacekeeper between the immigrants and his people. He was respected so much that the growing new city was named in his honor.

There was still much unrest. The pioneers moved onto land that the First People of Puget Sound had called home for thousands of years. The newcomers did not want to worry that the Indians would harm or bother them. Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens developed treaties that would give Native American tribes certain things -- like money, land, health care, and education -- in exchange for signing their land over to the government. It was important for Governor Stevens to have Chief Seattle’s support.

Chief Seattle was the first tribal chief to place his mark on the Treaty of Point Elliott. He could not write his name so he marked the treaty with an "X." It was difficult for him to understand the language of the treaty, but Seattle trusted the government leaders. Even after it became clear that the treaties did not provide what he had expected for his people, Chief Seattle kept his promises. During the "Battle of Seattle" he did not fight. Instead he stayed across the Sound at his home on the beach at Port Madison. He encouraged his people to do the same.

Seattle was well-known for his speaking abilities. Members of his family said that one of his spirit powers was thunder and that allowed his voice to be heard from long distances. He is best remembered for the speech that he gave when Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens first visited Seattle in January 1854. Dr. Henry Smith was one of those at the event and he described what he remembered in an article in the Seattle Sun Star.

Smith's story told of a large noisy crowd of Native Americans gathered along the shore. When Seattle’s voice was heard, there was sudden silence. Before he began his speech, the chief placed one hand on the Governor’s head. With his other hand, he pointed his finger towards the sky. People listened carefully to his words.

The words of this speech are often quoted. They describe what the First People valued about the land and the environment. They ask for respect of Native American rights. But there are several problems with this. First, Seattle spoke in Lushootseed. Smith took notes but Seattle’s words would have to have been translated into the Chinook Jargon and then to English. Second, the article with Smith’s memories was not published until 1887 – more than thirty years after Seattle's speech. We cannot be sure that Smith remembered Seattle's exact words.

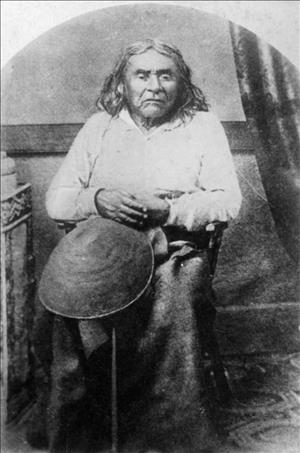

After the treaties, Chief Seattle lived mostly on the Port Madison reservation. His home was on the beach; it was called Old Man House. From time to time, he visited his old friends in the city that was named for him. About a year before his death, he went into a photographer’s studio to have his portrait taken. It is the only picture known to exist of Chief Seattle.

Seattle became sick with a high fever and died on June 7, 1866. It is thought that he was in his eighties. He was respected by his people and was recognized as a chief until his death. He was buried with both Catholic and native rites in the reservation cemetery at Suquamish. His good friend George Meigs owned a sawmill there and many Native Americans worked for him. Meigs shut down his mill the day of Seattle’s funeral so all could attend. One of Seattle’s last requests was that Meigs say goodbye to him by shaking hands with him in his coffin.

In 1890, a group of people placed a stone marker on Seattle's grave. The words on the marker point out that he was both a chief to his people and a friend to the whites. He will never be forgotten because the great city of Seattle was named in his honor.