Few places in Washington can match Port Townsend's long saga of soaring dreams, bitter disappointments, near death, and gradual rebirth. Located on Jefferson County's Quimper Peninsula at the northeast corner of the Olympic Peninsula, near where the Strait of Juan de Fuca meets Admiralty Inlet, the future town site was home to a band of the Klallam Tribe and smaller groups from other tribes. The first non-Indian settlers arrived in 1851, and Port Townsend, because of its position near the entrance to the sound, soon became Puget Sound's Customs Port of Entry and a bustling port, seemingly destined for greatness. But its progress was repeatedly thwarted, primarily by the absence of a railroad connection to the major markets then developing on Puget Sound to the south. It survived years of population loss and economic stagnation before the economy was stabilized by the opening of a paper mill in 1928. The city grew slowly over the following decades and gradually blossomed as a tourist destination noted for its natural setting, maritime charm, and many well-preserved homes and buildings from the late Victorian age. The Port Townsend Historic Landmark District was established in 1977, one of three surviving Victorian-era seaports in the nation.

Kah Tai

When Port Townsend (originally "Townshend") Bay was named in 1792 by British Captain George Vancouver (1757-1798), the area was occupied primarily by members of the Klallam (or S'Klallam) Tribe, who called the spot Kah Tai. They wintered in large communal cedar pole-and-plank homes along the shoreline, moving off in smaller family groups during warmer months to fish, hunt, forage, and trade.

Shore-dwelling Indians in the Northwest were early victims of diseases brought by sea-borne Spanish and British explorers. Starting in the late eighteenth century, they fell prey to smallpox, measles, diphtheria, and other pathogens that can no longer be identified with certainty. These plagues came in waves and went on for many decades. Records of the British Hudson's Bay Company estimated that as late as 1845 there were 1,500 surviving Klallams; less than 10 years later, the company counted only about 400. However, numbers vary widely depending on who was doing the counting and where. An 1855 census conducted by geologist and ethnographer George Gibbs (1815-1873) counted with impressive precision 926 surviving Klallams, more than double the Hudson's Bay total.

Shortly after Washington Territory was created in 1853, the first territorial governor, Isaac Ingalls Stevens (1818-1862), set about clearing much of the land of its indigenous inhabitants. The Klallam, and the Chimakum and Skokomish tribes, gave up most of their homelands in the January 1855 Treaty of Point No Point. They had little bargaining power, and the negotiations, if such they may be called, were conducted in Chinook Jargon, a trading tongue of limited vocabulary. Under considerable pressure, the tribes ceded their rights to nearly 440,000 acres of land, receiving in return a mere 3,480-acre Skokomish reservation on Hood Canal, the "right of taking fish at usual and accustomed grounds and stations," and $60,000 payable over 20 years (Treaty of Point No Point).

The Klallams living on the shore of Port Townsend Bay were loathe to move to the Skokomish Reservation, and most remained in place. Under two successive chiefs, S'Hai-ak (d. 1854) and his younger brother, Chetzemoka (1808?-1888), they lived on good terms with the early settlers. Chetzemoka, called the "Duke of York" by whites who had trouble pronouncing Indian names, visited San Francisco in the summer of 1851 (why and with whom does not appear in the record). There he met James G. Swan (1818-1900), a chronicler, ethnographer, lawyer, and all-around polymath who later would become an important figure in Port Townsend's history.

Chetzemoka saw white settlement as inevitable and maintained friendly relations with the newcomers, though that ultimately did little good -- nearly all the Indians in Port Townsend were ousted in 1871, their beach dwellings burned and their canoes towed to the Skokomish Reservation. Chetzemoka soon brought most of his band back to Port Townsend Bay, settling on Indian Island across from the town site. Many Klallams integrated with the area's non-Indian communities, while others gathered into four distinct groups: the Jamestown S'Klallam, the Port Gamble S'Klallam, the Lower Elwha Klallam, and the Sc'ianew First Nations on Vancouver Island.

The First Settlers

William R. "Blanket Bill" Jarman (1818-1912) arrived at Port Townsend Bay by canoe in 1848 and lived for some time with the family of Chief S'Hai-ak (later called "King George" by settlers). He was the first outsider known to have done more than pass briefly through the area on the way to somewhere else, but he claimed no land and did not put down permanent roots.

In the early 1850s, the trading brig George Emery under Captain Lafayette Balch (1825-1862) sailed frequently back and forth between San Francisco and Puget Sound, carrying mostly timber and often stopping at Port Townsend Bay. In August 1850, Henry C. Wilson (1812-1862), a clerk on the ship, disembarked there and filed a donation claim on the western shore. Although he did not immediately take up residence, he would later return, and Wilson's was the first recorded legal claim on Klallam land at Port Townsend.

Two bachelors, Alfred A. Plummer (1822-1883) and Charles Bachelder, passed Port Townsend as passengers on the George Emery while heading for Port Steilacoom, a trading depot farther south on Puget Sound. Balch encouraged the two to settle on the Olympic Peninsula, and after working at Port Steilacoom for a time they obtained an Indian canoe, paddled north, and came ashore on April 24, 1851, near Point Hudson. They filed donation claims on land about a mile from Wilson's and built a two-room, 15- by-30-foot cabin (at what is now the corner of Water and Tyler streets), becoming Port Townsend's first permanent non-Native settlers.

Plummer and Bachelder were soon joined by Loren B. Hastings (1814-1881) and Francis W. Pettygrove (1812-1887), two family men looking for a new place to settle. Pettygrove had come to Oregon Territory by sea in 1843 and cofounded the city of Portland. In 1849 he and Hastings traveled together to the California gold rush and did well selling supplies to gold seekers. They decided to move with their families to Puget Sound, and in October 1851 the men traveled down the Columbia River, up the Cowlitz, then overland to Olympia and finally by canoe to Point Hudson. There they were met by Plummer and Bachelder, and the four agreed to form a partnership and create a town. Hastings and Pettygrove staked claims on the bay between those of Plummer and Bachelder to the north and that of Wilson to the south. They returned to Portland, where Hastings purchased a 60-foot schooner, the Mary Taylor. In February 1852 (some sources say February 15, some the 21st, and others the 23rd), the Hastings, Pettygroves, and one other family left the ship in Port Townsend Bay and took up their new lives.

The Klallams were friendly and helpful to these first settlers, but Chief S'Hai-ak wanted compensation for the land they were claiming as homesteads. He was given some trade goods and told that the U.S. government would eventually pay for the land, a promise the newcomers may well have believed to be true. Then there was a rift among the settlers: Charles Bachelder had a liking for strong drink (something all had agreed to avoid), and his interests were bought out. The three remaining partners soldiered on, building a warehouse and starting a fish business (the town's first commercial enterprise) and a trading post.

A Curious Choice

As the city developed, it took on a roughly triangular shape, with the apex at the tip of Point Hudson, pointing east, broadening as it grew inland to the west. Many of the early arrivals took homesteads in Happy Valley (so named by Loren Hastings), a three-mile swath of fertile but swampy land that lay in the north half of the triangle, between the open Strait of Juan de Fuca on the north and the northwest shore of Port Townsend Bay near Point Hudson on the south. The place the settlers chose for a commercial center was south of that, and far from ideal. There much of the shore was separated from the uplands by a high bluff, just one of several topographical challenges. As later described by architectural historian Carolyn Pitts:

"The new residents built log cabins at scattered locations in the surrounding area. The topography and dense forestation of the [site] presented many difficulties that influenced early patterns of development. The lagoon at Point Hudson was essentially a depression produced by shifting sand and the remaining beach was susceptible to flooding because of its elevation. What little land that remained in front of the bluff was cut off at high water from the beach farther down the bay which, although the bluff tapered off, was useless as it was a continually flooded marshland. On top of the bluff, the plateau was impenetrable; a dense undergrowth everywhere except along the edge" (NRHP Nomination Form, 2).

At the end of 1852, Port Townsend's non-Indian population was just the three families and 15 single white men, living on a problematic site. But the dearth of other settlements on the Olympic Peninsula and Port Townsend's position at the gateway to Puget Sound would soon give it prominence beyond its size.

The Power of Place

Jefferson County was established as part of Oregon Territory on December 22, 1852, and Port Townsend was named county seat, although it may not legally have been a town at all. Some sources date the first plat to 1852, and that is certainly when Hastings and Pettygrove made their claims. However, the first formal plat map appears to be one that was recorded with the Jefferson County auditor on August 2, 1856. It showed 144 lots, most of which were on top of the bluff. The proposed route of aptly named Water Street, which would become the town's main downtown thoroughfare, was partially submerged much of the time, and the only buildable lots along the waterfront lay between it and the bluff, a distance of about one city block.

Washington Territory was created on March 2, 1853, and in 1854 the headquarters of the Puget Sound Customs Collection District was moved to Port Townsend from Olympia. A federal district court was established that same year, and in 1855 Dr. Samuel M. McCurdy (1805-1865) opened the privately owned Marine Hospital to provide medical services to seamen and quarantine for those carrying contagious diseases. In 1856, the U.S. military established Fort Townsend about four miles down the bay near Chimacum Creek, which was the nearest reliable source of good water. The fort was built to protect the town's citizens from Indian attack, but many believed it was too far away to be of much use.

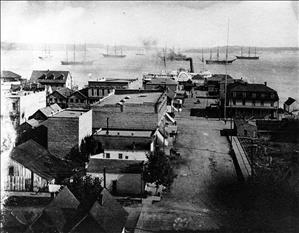

Much of the town's early economy was based on barter, as there was little cash around and little to buy with what there was. But every ship arriving from foreign ports had to stop at Port Townsend to clear customs, and many domestic vessels also stopped before sailing down Puget Sound to Seattle and other growing communities to the south. In 1858, D. C. H. Rothschild (1824-1886) opened the Kentucky Store, the town's first general mercantile establishment. That same year, Charles Eisenbeis (1833-1902), who would later become the city's first mayor, opened a cracker factory, primarily to supply hardtack to visiting ships. The first deep-water wharf was built in 1859 by Captain Ernest Fowler, who would also, in 1871, erect the city's first stone building. By 1860, Port Townsend's population was 264, enough to make it the seventh-most-populous place in the territory.

Optimists, particularly those with sizeable stakes in its prosperity, began calling Port Townsend such things as the "Key City" of Puget Sound and the "New York of the West," expressions of hope far more than reality. Not everyone shared these rosy views, and contemporary opinions about Port Townsend and its future ran the gamut from bullish hyperbole to scathing contempt. In 1856, J. Ross Browne (1821-1875), an inspector for the U.S. Treasury Department, reported:

"The streets of Port Townsend are paved with sand, and the public squares are curiously ornamented with dead horses and the bones of many dead cows. This of course gives a very original appearance to the public pleasure grounds and enables strangers to know when they arrive in the city, by reason of the peculiar odor, so that, even admitting the absence of lamps, no person can fail to recognize Port Townsend in the darkest night" (Morgan, "J. Ross Browne ...").

The residents of Port Townsend begged to differ, quite vociferously, and Browne later issued an apology of sorts.

A petition was made to the territorial legislature in December 1859 to incorporate Port Townsend and grant a charter for self-rule. Among those signing were Hastings, Plummer, Pettygrove, and Henry C. Wilson, who had returned to take up his 1850 claim. The legislature granted the request on January 16, 1860, making Port Townsend the fourth incorporated city in the territory, after Steilacoom, Olympia, and Vancouver. Under the charter, a five-member board of trustees (later reduced to three) was elected, and it appointed a clerk and a marshal. In 1882, the legislature changed Port Townsend's governance to the mayor/council form, and it later changed again, to a city manager and council.

With incorporation, Port Townsend had the power to handle its own affairs, some of which soon became rather complicated. Victor Smith (1827-1865), appointed federal customs collector in 1861, had views similar to Browne's, and professed himself unhappy that a place like Port Townsend was an official port of entry to the United States and its territories. After describing the city as "a collection of huts," he recommended that its federal functions be moved west down the Strait of Juan de Fuca to Port Angeles, a place far less developed than Port Townsend, but where Smith happened to be speculating in land (Morgan, "Victor Smith ..."). His dogged efforts were successful, and on June 18, 1862, Congress authorized moving the customs district headquarters. Port Townsend residents resisted, claiming, among other things, that Smith had embezzled from the customs accounts. But Smith was determined; he threatened to shell Port Townsend from the lighthouse tender U.S.S. Shubrick if the customs-house files were not turned over. They were, and he decamped with them to Port Angeles. Smith drowned in 1865, and Port Townsend was able in 1866 to reclaim its status as headquarters of the Customs District of Puget Sound, ensuring its survival, if not its future prosperity.

Getting By, But Not Big

The bloody Civil War and its aftermath preoccupied the nation during much of the 1860s, and although it was remote from the battlefields, the march of progress in Washington Territory slowed. The federal census of 1870 counted 593 non-Native residents in Port Townsend, a little more than twice the 1860 count and enough to make it then the fourth-largest city in the territory after Walla Walla, Olympia, and Seattle (in that order), but with barely half the population of the latter.

The nation's economy slowly returned to normal after the war. Rumors of railroads fueled a building boom in Port Townsend that began in the early 1870s, but for the time being the city got by with a mix of agriculture, logging, and catering to the maritime trade. Chandleries carried ship supplies of every description, and hotels, saloons, and bordellos were built to house and entertain the steady stream of seamen passing through. It was estimated that half the ships entering Puget Sound picked up crew in Port Townsend, and "crimping," or shanghaiing, was not uncommon and would continue for many years.

But technology was advancing, and as steam-powered vessels increasingly replaced sail in the 1870s and 1880s, the fluky inland winds of Puget Sound became largely irrelevant to navigation. If steamships didn't have to stop at Port Townsend for customs inspection, they often didn't stop at all. Hopes for a ship-building industry did not pan out, due mostly to the early exhaustion of the supply of suitably tall trees from nearby forests. No doubt for the same reason, the area's first large sawmills went in not at Port Townsend, but at Port Ludlow 15 miles to the south and at Port Gamble on the Kitsap Peninsula to the east. Nor did the arable land near the city produce enough to support an agricultural export trade of any appreciable size, although Port Townsend's wharves also handled produce from other area communities.

The mix of activities supported steady if very slow growth, and by 1875 there were 66 Port Townsend businesses listed in a regional directory. The first brick home, owned by Hiram Parrish (1856-1931), was built in 1878 with bricks made in Happy Valley by S. M. Eskildsen (1850-1936). By 1880 the population had increased to 917, but faster growth elsewhere made the city again only the seventh-largest in the territory. Port Townsend was surviving, even growing somewhat, but it was losing ground to other territorial population centers.

The Railroad Problem

One person who did not share Browne's and Smith's dyspeptic views of Port Townsend was James G. Swan. Originally from Massachusetts, he had spent three years on Shoalwater (later Willapa) Bay on the Washington coast, and then served as secretary to Isaac Stevens when Stevens was a territorial delegate in Washington, D.C. Swan moved to Port Townsend in 1859, and described the community he found:

"During the last eight years, the growth of the town has been gradual but permanent, and it now numbers 300 inhabitants. There are between fifty and sixty buildings in the place ... . There are two good wharves ... and the facilities for business accommodation are equal to any I have yet seen in the Territory. ...

"... If Mr. Browne's report was correct, there certainly has been a wonderful change for the better. The 'beach-combers' and 'outlaws' as Mr. Brown designated the inhabitants — with very few exceptions — have left the place" (Almost Out of the World, 12-13).

The citizens of Port Townsend placed much of their hope for the future on the coming of the railroad, and like those in many other pioneer towns they would suffer bitter disappointment. Perhaps no one suffered more than Swan, who for nearly 30 years struggled to link his city by rail to the wider world. He was seemingly well placed to do so; he served from 1867 to 1871 as an agent of the Northern Pacific Railroad, hired to study and recommend sites for a western terminus that would extend the company's line northward from Portland into the rapidly growing Puget Sound region. Swan of course recommended Port Townsend, but in 1873 the railroad ignored his advice and chose Tacoma.

Despite this disappointment, between 1880 and 1890 Port Townsend's population grew by nearly 400 percent, to 4,558. While this looks impressive enough in isolation, during the same decade Seattle's population increased by more than 1,100 percent, Tacoma's by nearly 3,500 percent, and Spokane's by nearly 5,300 percent. People were pouring into the Northwest, but the vast majority of them were settling somewhere other than Port Townsend.

Nevertheless, dreams of a rail link persisted, and some of the town's leading citizens eventually decided to take matters into their own hands. On September 28, 1887, the Port Townsend & Southern Railroad was incorporated and announced plans to run tracks south to Hood Canal, then on to Olympia. The hope (couched more as a promise to prospective investors) was that one of the major railroads would see this as an opportunity, take over the completed line, tie it in with the transcontinental system, and empower Port Townsend to compete with the down-sound cities that were fast outstripping it in every quantifiable category. Rights of way were purchased in 1888 and construction began in early 1889, but the money ran out after a mere mile of track was laid.

Later in 1889 (the year Washington gained statehood), the Union Pacific offered to make Port Townsend the northern terminus of its transcontinental line, if it could acquire the Port Townsend & Southern's franchise and rights of way, and if the city kicked in $100,000. The citizenry was swept again by railroad dreams, and the town's newspaper, the Leader, predicted: "This day means a great deal more to us than we are aware of at present ... . Port Townsend will now get its share of the wealth and commerce of Europe that annually finds its way hither and has heretofore passed us by" (City of Dreams, 215).

Some outsiders were more clear-eyed, but no one was listening. In an 1889 report prepared for the Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern Railway, which also was looking to expand, attorney W. H. Ruffner summed up the fundamental geographical nature of the problem: "The location of Port Townsend puts that town out of the general competition ... " ("A Report on Washington Territory"). There simply was no compelling economic rationale for a rail link to the still-remote tip of the Quimper Peninsula.

But dreams die hard. The Union Pacific's conditions were met, and on October 2, 1889, a groundbreaking ceremony two miles west of town drew practically the entire population to hear speeches proclaiming impending glory. Work was to begin simultaneously at Portland and Port Townsend, and everyone looked forward to the day the two would join, ending Port Townsend's isolation and realizing its long-held ambitions. Property values soared, and in 1890 alone real-estate transactions in Port Townsend totaled nearly $4.6 million, and this in a city with barely 4,500 residents. Before that year was out, the city boasted six banks, six dry-goods stores, six hardware stores, 10 hotels, 28 real estate offices, and three street-car lines. Flush with optimism, Port Townsend started to build an impressive new city hall on the corner of Water and Madison streets.

Fittingly, as it would turn out, the contract to start railroad construction south from Port Townsend was let on April Fool's Day, 1890. By June, 2,000 men were at work. A depot, roundhouse, and railyard were being built on landfill at Kah Tai Lagoon at the south end of the city, and by September there were trains running daily to Leland Lake, about twenty miles away. While the rails were heading south out of town, two grand symbols of optimism were rising in the city. On the bluff above downtown, construction began in 1891 on the Romanesque Jefferson County Courthouse, complete with a 124-foot clock tower. It opened late the next year. Beneath the bluff, at the corner of Madison and Water streets, the new city hall also opened in 1892. Both buildings were added to the National Register of Historic Places in the early 1970s, and both were renovated in the first decade of the twenty-first century.

Despite all the apparent progress, things were starting to go badly wrong. In the south, Union Pacific's subsidiary, the Oregon Improvement Company, had been devoting its energies to unsuccessful land speculation rather than laying track, and it went into bankruptcy receivership in November 1890. In the north, the railroad was completed as far as Quilcene, where, according to railroad historian Steve Hauff, "somebody noticed that Mount Walker was there. They found there was really no way to get around this, and that was the end of it" ("Railroads Gone ... "). And the end it was, at least of any realistic hope that Port Townsend would become a leading city in the young state.

On the heels of the local railroad debacle came the national financial meltdown known as the Panic of 1893, which was triggered in part (with particular irony for Port Townsend) by railroad overbuilding and debt. Commerce in the city slowed to a near stop, and the bay became a watery warehouse for a fleet of unused vessels left to slowly rot at anchor. Property values plummeted; like the railroads, the city had drastically overbuilt. Downtown buildings stood vacant, streetcar lines were torn up, and all but the most avid and unrealistic city boosters fell silent.

The city had a brief bright moment in March 1893, when the federal government completed the Port Townsend Post Office, Court, and Customs House on the bluff above downtown. Construction had begun in 1885, and the steel and brick, sandstone-clad building was finished several years late and several times over budget. It was an impressive edifice, but almost contemporaneous with its dedication, people started abandoning the city in droves. Between 1890 and 1900 nearly one-fourth fled, leaving behind a population of less than 3,500. Port Townsend would never again be counted as one of the 10 most populous cities in the state, and it fell into a deep and prolonged decline.

There would be brief outbursts of train hysteria in later years, unrealistic dreams sustained by little more than rumor and vestigial boosterism. The little line to Quilcene ran on until the 1980s, almost always at a loss, and was said to have changed ownership more than any other railroad in the entire country.

A Triangle of Fire

Few could have been more disappointed than James Swan, but he was an optimist by nature, and before he died in 1900 he was able to perform one last service for the city he loved. The federal government had seen little need for heavy fortifications on Northwest waterways, but in 1891 the Puget Sound Naval Station was established at Bremerton, and it required protection. Fort Townsend was too far from Admiralty Inlet to do much good and had been heavily damaged in a fire. It was closed in 1895, kicking another small crutch out from under the struggling city. But the following year, Congress passed a huge allotment for military fortifications and Swan, who was widely respected and had many contacts in Washington, D.C., lobbied hard to bring some of that money to Port Townsend. While the extent of his influence cannot be accurately judged, the federal government decided to built three forts that together could cover Admiralty Inlet with triangulated artillery fire -- Fort Casey, on Whidbey Island's Admiralty Head across from Port Townsend; Fort Flagler on the north end of Marrowstone Island; and Fort Worden, on the northern outskirts of Port Townsend at Point Wilson. All were substantially completed by 1902, and Fort Worden was designated Coastal Defense Headquarters.

These facilities did not lead to great prosperity for the city, but their construction and presence did provide a lifeline when it was most needed. Over the ensuing years, the forts' economic contributions varied with their state of activation. In threatening times and during war, troop levels increased and the local economy benefited. In peaceful times or times of government belt-tightening, the forts were more lightly manned, and nearby communities suffered. They were no replacement for the boost a rail link would have brought, but they helped keep Port Townsend alive when it had few other prospects.

The Mill and the Military

The forts' modest boost helped the city's population to increase between 1900 and 1910, albeit by barely 700 souls. But the military presence may have been a mixed blessing. A comprehensive study of the city's educational system in 1915 noted:

"[T]he fever of old boom days has not been completely lost from the blood; the will to work at the immediate task is not fully present, and the presence of the military with its easy money tends to keep alive the feeling of a glorious past that will surely come again" (Lull, 9).

This may have been a subjective and overly harsh conclusion, but the report did highlight a very real threat to the city's future.

"The most universal remark which one hears from the young people and from the old too, is this: 'Why should a young man remain in Port Townsend? There is nothing for him to do here.' ... Port Townsend is now playing a losing game; it is educating its young people for a life that they will lead elsewhere" (Lull, 10).

The bleakness of the situation should not be overstated, however. The sun still shone on Port Townsend, and the beauty of its natural setting made up for much. Many residents were solidly middleclass, by the measure of the day, and a fortunate few got rich. Like any city, Port Townsend had its share of murders, scandals, mysterious disappearances, divorces, and other events to keep the citizenry entertained. But for most of the first 30 years of the twentieth century, and particularly after the customs headquarters moved to Seattle in 1911, it lay largely outside the flow of historical events, a small, quiet city on a quiet peninsula. It enjoyed a brief, moderate boom during World War I, but by 1920 the population had fallen back to 2,847, the lowest since the mid-1880s. In 1924, county voters approved the formation of a public port district, but a persistent lack of financing ensured that it would accomplish very little until the 1950s. Some in Port Townsend may still have dreamt of greatness, but the decades of false hope had taken their toll.

Finally, in 1927, a single, large, stable employer came to town. The Zellerbach Corporation of San Francisco, through its subsidiary National Paper Products Company, announced in July of that year that it would build a kraft-paper plant at Glen Cove, about three miles down the bay from Point Hudson. The plant would require vast amounts of fresh water, and Port Townsend promptly applied for and received water rights to the Big Quilcene and Little Quilcene rivers. In addition to providing immediate construction jobs and long-term employment opportunities, the company absorbed much of the cost of rebuilding the city's aged water-supply system. More than 600 workers were hired to build the plant. The new water system was activated on October 5, 1928, and the mill started production the next day. In 1929, the Crown Zellerbach Port Townsend Mill, as it was then called, had 275 employees and an annual payroll of $325,000. Of equal importance, the gravitational pull of such a large enterprise drew a wide range of supporting businesses to the city. By 1930 the population had rebounded to 3,970, up nearly 40 percent over 1920 and the largest census count since the boom times of 1890. To the great satisfaction of those with long memories, Port Townsend remained relatively prosperous throughout the dark years of the Great Depression, and for the first time in many decades was the object of some envy.

In 1940 the city's population reached a new high of 4,693, and it increased further with the arrival of approximately 2,500 military personnel after America's entry into World War II in December 1941. The war brought prosperity; the Crown Zellerbach mill ran 24 hours a day, and soldiers from the three nearby forts spent their leave and their money in town. By 1950 the population had grown to 6,888, but the stimulus provided by the military tapered off with demobilization and ended with the closure of the forts. Fort Flagler and Fort Worden closed permanently in 1953 and Fort Casey in 1956. All became state parks and continued to benefit the region as tourist attractions. Fort Worden gave the city an additional if temporary economic boost in 1981 when it was used as a location for the hit movie An Officer and a Gentleman.

Due to the fort closures, by 1960 the city's population had fallen by more than one-quarter, to 5,074, and many in Port Townsend must have felt the boom-and-bust history was being dismally repeated. But there was one big difference this time -- the paper mill stayed. It remained the county's largest employer and still supported a bevy of related businesses. Once again, the city clawed its way back, and after the setback of 1960 the population grew in every census, reaching 9,113 in 2010.

A City in Amber

The building boom of the 1880s and early 1890s left Port Townsend's downtown streets lined with impressive buildings characteristic of the period, and a number of its notable mansions remained well-preserved. The predominant styles were variations of late-Victorian architecture. Many of the downtown buildings sat empty for years, but relatively few were destroyed, either for lack of funds or lack of other uses for the property they sat on. Left largely untouched, they eventually proved to be of considerable benefit.

In 1961, Seattle architect and preservationist Victor Steinbrueck (1911-1985) gave a lecture in Port Townsend sponsored by the city's Art League and Chamber of Commerce. He told the assembled, "Port Townsend is a museum and you are the caretakers" (City of Dreams, 114). His words were taken to heart, and the city first drew on its architectural legacy in January 1963 with a showing of just one of its historic homes, the Saunders House at the south end of town. The organizers of this first Homes Tour expected two or three hundred visitors at most; nearly 2,000 showed up, causing a huge traffic jam. It was clear they were on to something.

The Homes Tour became an annual event of increasing popularity, and the people of Port Townsend quickly came to realize that their city, however inadvertently, had preserved the only largely intact Victorian seaport on the West Coast. Beginning in the early 1970s, the city, the Port of Port Townsend, and others worked to gain official recognition for the historic waterfront and the nineteenth-century residential area located on the bluff above downtown. Both were placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1976, and a year later the area encompassing them was designated a National Historic Landmark District, as was the former military base at Fort Worden.

It was also in 1977 that the city hosted North America's first-ever Wooden Boat Festival at the Point Hudson Marina (owned and operated by the port district), and this led to the 1978 creation of the Wooden Boat Foundation, which sponsored the event in later years, always drawing crowds in the thousands. In 2008, the foundation opened its Northwest Maritime Center, sponsor of everything from boat-repair classes to regattas, and home to the Wooden Boat Chandlery, a one-stop shop for boat lovers.

By 2014, in addition to the historic landmark district, Port Townsend had at least 25 individual buildings listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The largest employer remained the Crown Zellerbach mill, but a thriving boat-building industry -- everything from small wooden sailing craft to large mega-yachts -- had developed, along with numerous facilities, large and small, for ship repair.

As the city's charms became more widely known, it drew increasing numbers of retired people and empty-nesters, and many brought with them the desire and the means to help Port Townsend preserve its heritage. In 2000, the city was awarded the Great American Main Street Award, a national prize recognizing preservation-based economic-revitalization efforts. Several of the city's historic houses were converted to bed-and-breakfasts, and in its well-preserved downtown district visitors shopped for everything from antiques to zucchini. In 2006, a major restoration of the nineteenth-century City Hall, home since 1951 to the Jefferson County Historical Society, was completed.

The first 75 years of Port Townsend's history were a roller coaster of high hopes, big gambles, bad breaks, and deep disappointments. With the coming of the Zellerbach mill in 1928, the city settled into a long period of relative economic stability, but with greatly lowered expectations. While dreams of becoming the New York of the West did not come close to realization, most who live in Port Townsend today, surrounded by the area's natural beauty and the well-preserved architecture of the past, would probably say that things turned out just fine, after all.