Seattle's KRAB radio was the fourth commercial-free, listener-supported radio station in the United States when it took to the air at 107.7-FM in December 1962. It was founded and initially financed by Lorenzo W. Milam (1933-2020), a young man of means and a mission to develop subscriber-supported radio. Throughout its 21-year history, KRAB aired a mix of programming that the word eclectic does not adequately encompass. Regular fare included esoteric music played on unfamiliar instruments; readings of poetry and literature, occasionally in Sanskrit and other tongues no longer widely spoken; free-wheeling panel discussions on practically any topic; often-brilliant commentaries on just about everything; and generous servings of jazz, bluegrass, Dixieland, and seldom-heard Western classical compositions. KRAB was kept afloat, if barely, by subscriptions, donations, and occasional grants, and remained resolutely free of advertising. During a tumultuous two decades, it kept its listeners informed, entertained, and often bemused by things they had never heard before and would probably never hear again. Despite the labors of a mostly volunteer staff, the station nearly always danced on the edge of a financial precipice and came to a controversial end in April 1984 after its assets were sold to a commercial broadcaster.

The Birth of Community Radio: The Pacifica Foundation

Listener-supported FM radio got its start when Lewis Hill (1919-1957) moved to San Francisco from Washington, D.C., in 1946 and began planning a new kind of radio station -- supported by the public, uninfluenced by advertisers, free to air a range of non-traditional programming. With others, he formed the Pacifica Foundation, and on April 15, 1949, KPFA-FM took to the airwaves from a studio in Berkeley, California.

KPFA gave voice to those largely excluded from mainstream media and had as regular presenters such avant-garde figures as poets Allen Ginsberg (1926-1997) and Lawrence Ferlinghetti (1919-2021) and British-born philosopher Alan Watts (1915-1973), author of the best-selling Way of Zen. Controversy was always near at hand; in 1954 the tape of a rather stoned panel discussion on the effects of marijuana was confiscated by the California attorney general, and the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) found occasion to complain that some KPFA content was "vulgar, obscene and in bad taste" ("Pacifica History"). Nonetheless, Pacifica/KPFA was awarded a George Foster Peabody Award in 1957 in recognition of its "distinguished service" in opposing McCarthyism ("Pacifica History").

In 1959, Pacifica's second station, KPFK-FM, went live in Los Angeles. The following year philanthropist Louis Schweitzer (1899-1971) donated WBAI, a commercial radio station in New York City, to the foundation and it became the third non-commercial, listener-supported FM station in America. Sadly, Lewis Hill missed these developments. Having lost control of Pacifica and plagued by ill health, he committed suicide in 1957.

Enter Lorenzo Milam

Lorenzo Wilson Milam's love of radio went back to his childhood in Jacksonville, Florida, where his father was a prosperous real-estate speculator. Milam listened for hours to broadcasts from Nashville, New Orleans, and other cities, often from stations that catered to African Americans. He later explained the fascination:

"We were spying on another culture, weren't we? — for in the segregated south, we knew nothing of the culture, the art, the exquisite music of the blacks because we never ventured into that part of town ... But we could eavesdrop by radio" (Walker, 55).

Milam attended Yale University in 1951, worked on the student radio station, and after a year landed a job back in Jacksonville at a commercial AM station, WIVY. He was then stricken with polio, and after nearly two years of ineffective and painful treatments went to the Warm Springs Foundation in Meriwether County, Georgia, established in 1927 by Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945), another adult victim of the disease. There his condition improved enough to permit him to ambulate with crutches, and he got on with his life, a good portion of which would be dedicated to radio. He enrolled at Haverford College, a Quaker school in Pennsylvania, where he worked on the campus station and became a committed pacifist. After another brief radio stint in Jacksonville, he moved to Berkeley to work toward a master's degree in English, where he soon signed on as a volunteer at Pacifica's KPFA.

In 1958, Milam applied to the FCC for a license to start a radio station in Washington, D.C. It was during the Cold War, and any hint of dovish sentiment could cause bureaucratic inaction. After two frustrating years without a clear answer one way or the other, he changed course and applied for a license to broadcast in Seattle, "as far as you could get from Washington, D.C. and still be in the contiguous states" (Walker, 67). Milam hired a law firm to process the application before moving to Europe for a spell. When he returned to America in late 1961, his application was approved, and he moved to Seattle to start a grand experiment.

KRAB-FM, 107.7

Milam began staffing his station in April 1962 with an ad in Broadcasting magazine:

"Be daring. Help our poverty-stricken operation start from nothing. KRAB (FM) 9029 Roosevelt, Seattle 15, Washington" (Broadcasting).

Although he was financially secure, Milam knew that radio could be a bottomless money-pit, and KRAB was intended to be a mostly volunteer, low-budget operation. The address given in the ad led to a ramshackle former donut shop north of the city's University District. Milam's first choice for call letters was KANT, but for unknown reasons, the FCC assigned him his third choice, KRAB. The available frequency, 107.7, was in the commercial portion of the FM spectrum and would in later years become a very valuable piece of the ether, causing no end of trouble. It was also about as far right as you could get on the FM dial (which went only to 108 MHz), a tiny irony that wasn’t lost on the station's generally left-leaning cadre of volunteers.

Milam purchased a houseboat on Lake Union for himself, then purchased another to provide housing for various station volunteers (Seattle houseboats in the early 1960s were ridiculously inexpensive). His earliest co-conspirator, Gary Margason, was a friend from his days at KPFA. His next was Jeremy Lansman, a 19-year-old, self-taught electrical whiz who was fresh from setting up an FM station in Hawaii. Lansman saw the ad in Broadcasting and came to Seattle, the only one of 30 or so respondents to show up in person. Legend holds that he was welcomed as the station's first engineer after demonstrating how he could pick up Radio Moscow by placing an antenna in Milam's refrigerator.

In June 1962, the City granted KRAB permission to build a 60-foot antenna. The station's first transmitter was a well-used 1946 Collins, ancient by broadcasting standards, filled with vacuum tubes, huge, heavy, temperamental, and so hot-running it doubled as a heater for the station's small headquarters. Lansman went to work on it, and by November 1962, he, Milam, and Margason were ready to give it a try. Huddled in the former donut shop, they flipped the switch. It was a very short broadcast; the transmitter "blew up almost the instant it went on the air ... [and] showered sparks all over the ground" (Program: "KRAB Nebula ... "). A second brief try was more successful. The first words spoken were not preserved, but Milam later speculated that they may have been "I don't hear anything" ("KRAB: The Ultimate ...").

Such setbacks were to be expected on the frontier of listener-supported radio. Lansman spent time tinkering and troubleshooting, and about a month later, at 5:00 p.m. on Thursday, December 13, 1962, KRAB-FM again flickered to life, broadcasting at 20 kilowatts. No record of the complete content of that first night's programming survives, although Indian music, which would become a station standby, apparently was involved. A column in The Seattle Times the following week gave a better idea of what KRAB had in store for its listeners:

"Most programs ... will pursue an 'open end' pattern, running an hour, two hours, or more. 'Time is unimportant to us,' Milam said. 'Our roundtable discussions will continue to their natural conclusion as the issues warrant.'

"Other programming features will be classical music not ordinarily heard on other stations; readings from the classics; drama and general commentary. This will include such way-out fare as Chinese operas and readings from Cicero in Latin with a jazz background" ("Broadcasting on a Shoestring").

The columnist was both bemused and impressed, and he closed with a benediction: "Milam and his volunteers rate a 21-gun salute for having the courage to try something different" ("Broadcasting on a Shoestring"). Milam, with considerable understatement, promised that KRAB "would be about a lot of things" ("Broadcasting on a Shoestring"). By the end of December, after the station's first two weeks on the air, Broadcasting magazine reported, without a hint of condescension: "KRAB has six subscribers so far" (Broadcasting, December 31, 1962). Not great, but a start.

Milam was station manager and Margason program director. Lansman was responsible for engineering and in charge of poetry and drama. Robert Garfias, an ethnomusicologist from Berkeley who knew Milam from KPFA days, moved north and became music director while also teaching at the University of Washington. By the time KRAB went live, Milam had rounded up eight volunteer commentators and promised that a range of opinions, from the far left to the far right, would be represented. One of the first commentators was Jon Gallant, a biochemist and geneticist at the University of Washington who had roomed with Milam in college and would stay with KRAB for many years.

KRAB's first published program guide covered the middle two weeks of February 1963. It was distributed free, but circulation of later editions was limited to subscribers at an initial cost of $12 a year, eventually raised to $25. A few items scheduled to air on February 11 convey the flavor: Jean Cocteau's "The Human Voice," as read by Ingrid Bergman; "The March Retreat," a recapitulation of the German offensive of 1918, as told by the men who were there; the music of Chollado province in South Korea, presented and described by Robert Garfias; and a panel discussion on "Approaches to Medical Care for the Aged" (KRAB Programming Guide No. 1). Subsequent nights offered a festival of music from the Middle Ages, readings by Seattle poets and writers, Arabic and Turkish classical music, and Finnish folk poetry read in Finnish. There was also more conventional fare -- lesser-known works by Mozart, Vivaldi, Schubert, and others; generous portions of jazz, Dixieland, and bluegrass; and legislative reports from Olympia. Even a regular "Children's Program" did not escape KRAB's wry touch: "READINGS FROM WINNIE THE POOH. Several children protested last week's Freudian interpretation of the Milne work, and as recompense, we will read the work straight, without footnotes" (KRAB Programming Guide No. 1).

Lorenzo Milam used the station's semi-weekly program schedules as an outlet for his considerable talents as an essayist and for an ongoing effort to explain just exactly what KRAB was about. In Issue 1, he noted that 55 people had been heard on the air since the station went live:

"Fifty-five persons, with fifty-five different views. We were delighted that there were so many, and wished there could be hundreds more — for we see radio as a means to the old democratic concept of the right to dissent, the right to argue, and differ, and be heard ... " (KRAB Programming Guide No. 1).

Because its programming was so diverse, KRAB's format defied concise definition, even by its founder. Milam at some point hit upon the term "supplementary radio" -- KRAB would not copy what was available from other broadcasters, but would supplement their offerings with things that otherwise would probably never be heard on Seattle's airways. He would use the phrase often, if sometimes cryptically:

"The principle of supplementary radio [is] that in every community there should be one outlet that knows and accepts the fact that none of its programs will appeal to all of the people all of the time (or, conversely, that none of its programs will appeal to some of the people much of the time)" (Radio Papers, 22).

In a medium that paid slavish attention to the clock, KRAB's published schedules were advisory, perhaps aspirational, but rarely mandatory. Interesting discussions often ran long, while occasional debates that became too contentious or meaningless to continue on-air might end early. Conventional radio stations believed every second of airtime needed sound -- talk, music, ads, whatever, but sound of some kind. KRAB embraced the beauty of silence, and often followed a particularly moving musical passage or cogent bit of commentary with a short period of "dead air," allowing the effects to sink in. Most stations hired announcers with trained, mellifluous radio voices; KRAB couldn't and didn't, and liked it that way. Its volunteer announcers "might stumble and worry, but they are alive," Milam wrote (Radio Papers, 7).

KRAB's determination to provide a distinctly different radio experience did not always mesh well with its determination to survive on the generosity of listeners. Broadcasting into the void hours of Balinese folk music or poetry readings in obscure, perhaps dead, foreign tongues was seen as having intrinsic value. The possibility that absolutely no one was listening added an appealing touch of existential absurdity. But there always was the competing hope that an unseen sea of listeners sat hunched over their radios eagerly awaiting such things, and that they would show their appreciation by sending money, and lots of it, to the only station that would dare provide them. The actuality would fall somewhere in between; at its peak, KRAB had about 2,500 subscribers, but the usual count was considerably smaller.

The Jack Straw Memorial Foundation

It was never Lorenzo Milam's intention to own a radio station over the long term. His mission was to bring them into the world, nurture them until they could stand on their own, then get out of the way and hope that they would grow up to be independent, unruly adults. On June 1, 1962, he, Margason, and Gallant incorporated the Jack Straw Memorial Foundation for "the establishment and operation for educational and cultural purposes of one or more radio broadcasting stations" (Articles of Incorporation). The three served as the foundation's first officers and trustees, with Milam as president.

Jack Straw was an appropriately obscure namesake, either a leader of England's Peasant Revolt of 1381 (perhaps under the name John Rackstraw) or the alias of another ill-fated rebel, Wat Tyler (d. 1381). It is certain that, whoever he was, Jack Straw's severed head was displayed on London Bridge when the revolt failed. Shortly thereafter he was mentioned in passing by Chaucer (1343?-1400) in The Canterbury Tales.

On March 25, 1964, the FCC approved the transfer of KRAB and all its assets from Milam to the Jack Straw Memorial Foundation, at no cost to the latter. A little more than a year later, the foundation was granted tax-exempt status, making supporters' contributions tax deductible. Operationally nothing changed for many years, but the station would remain under foundation ownership until it signed off the air for good nearly two decades later.

Lost Innocence

By June 13, 1963, KRAB had picked up 181 subscribers, about one for each day it had been on the air. The fact that it had survived even this long was seen as a minor miracle, and The Seattle Times took note:

"This evening at 8:30 the station staff will offer a roundtable report on KRAB's half year of 'steady (and nervous) broadcasting.' The program's unflinching title: 'After Six Months, What the Hell'" ("KRAB Quandary ... ").

Within six more months, dismal numbers had demonstrated that KRAB could not survive on an average of one new subscriber a day and was slipping deeper into debt. Something had to be done, and promptly at 12:01 a.m., November 9, 1963, KRAB became the first noncommercial media outlet to do an on-air fundraising marathon. For 42 straight hours, it promised, KRAB would broadcast

"music and parts of the most unusual lectures, discussions, concerts, commentaries that were heard over the station for the past year. Pledges will be solicited at disarmingly frequent intervals, and we will have a squad of motorcyclists (to be identified by hearts & 'KRAB' tattooed on their arms) ready to go out and pick up the pledges" (KRAB Program Guide No. 23).

It was successful -- the station raised about $1,000, equivalent to more than 80 new subscribers. But to many, including Milam, this exercise had brought KRAB perilously near to much that was disliked about conventional broadcasting. As he pointed out in his next program essay:

"[T]hat 42 hours was as close to commercial radio as KRAB has ever come ... . Some pleas, especially in the last hour or so, were so impassioned that they made us want to weep with the self-pity of us ... Until the time of the Marathon, we avoided selling ourselves: as we have said so often, KRAB was established to traffic in ideas, not in commerce" (KRAB Program Guide No. 24).

Despite misgivings, these marathons became a regular financial lifeline for many years, held at intervals that coincided with budgetary crises. The idea was soon picked up by noncommercial and educational radio and television outlets across the country and proved effective at trying the patience while prying open the purses of audiences. The unavoidable fact, proved first by KRAB, is that concentrated begging works; without it many non-commercial media outlets simply could not survive.

KRAB found other support as well. In 1965 Louis Schweitzer (who many years earlier had gifted WBAI to the Pacifica Foundation) donated IBM stock worth $10,000 to the station, conditioned on it obtaining matching funds locally. The following year, the Seattle arts charity PONCHO matched the gift, and the combined money was used to purchase a site on Cougar Mountain for the eventual placement of a tower and microwave link to the broadcasting studio. Several years later, in 1972, another grant from PONCHO combined with funds from the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare allowed KRAB to complete the work, making it one of the few listener-supported stations in the country to own such an asset.

Plummeting Pianos and Other Fun Things

KRAB's on-air debut preceded by a few years the peak of the social and cultural ferment that swept America in the second half of the 1960s, but it proved a comfortable fit when the time came. Although rooted more in the beat era, the station's anything-might-happen approach to programming anticipated the hippy zeitgeist. Despite the station's years-long shunning of rock music (not "supplementary" enough), collusion between KRAB and the counterculture was all but inevitable. One of the first signs that the two had joined forces was "The Big Gigantic Noisy Spooky Party Light Show Orgy," a November 1966 KRAB fundraiser that was advertised to end only "when all the fuses and minds blow" (KRAB Program Guide No. 99). (Actually, an oft-replayed lecture by Harvard psychologist and LSD evangelist Dr. Timothy Leary [1920-1996], first aired on KRAB in June 1963, may have been an earlier indication that there would be a mingling of the tribes.)

On March 23, 1967, the first issue of Helix, Seattle's storied underground newspaper, hit the streets. Started by Paul Dorpat (b. 1938), Helix documented, entertained, informed, and often incited the city's youth in revolt. It was to traditional newspapers what KRAB was to traditional radio, and the two soon were sharing volunteers and exploring ways to raise money together. The first effort, on April 21, 1968, was "Media Mash," a joint (no pun intended) fundraising concert at Seattle's Eagles Auditorium that featured the Bay Area's Country Joe and the Fish and several local bands, including Magic Fern and Time Machine (Rites of Passage, 332).

Their second joint venture came just a week later and has ever since held a hallowed place in the recollections of those who were there, many who were not, and some who can't be sure one way or the other. Called simply The Piano Drop, it was an afterthought to the Media Mash, and Country Joe agreed to hang around and play again. The site was east of Seattle near Duvall on a farm owned by jug-band musician Larry Van Over. Country Joe aside, the real entertainment would be provided by a rented helicopter and an ancient upright piano bought at Seattle's St. Vincent de Paul charity for $25.

When the time came, nearly 3,000 people gathered in a pasture, eyes to the sky, ears awaiting the whup whup of rotor blades. Soon the helicopter appeared, the piano slung below, swinging back and forth like a giant inverted metronome, making it very difficult to tell exactly where it might end up if released. The crowd pulled back, and after much frantic urging by Van Over, the pilot let loose his load. The ancient Steinway plummeted about 150 feet to the ground, missing a pallet of logs and landing in the mud, not with the hoped-for explosion of wood, wire, and the epic closing chord of the Beatles "A Day in the Life," but largely intact, and with an unmusical thud. No matter, people were thrilled, and the success of the event was an inspiration later that year for one of the first multi-day outdoor rock gatherings, the Sky River Rock Festival & Lighter Than Air Fair.

Ministers, Mimes, and Naughty Words

KRAB managed to avoid negative FCC scrutiny for many years, but was always at risk of stepping over an ill-defined and highly subjective line of acceptable on-air behavior. Typical of the sort of unpredictable programming that might trigger unwanted attention were group-therapy marathons in 1967 and 1968 -- live, grueling, non-stop, 20-hour sessions of psychological striptease, punctuated by occasional outbursts of sobbing. But it would be the words of two men of the cloth and an interview with (of all things) a mime troupe that finally brought the FCC down on KRAB.

On the morning of August 5, 1967, KRAB began airing a 30-hour tape of an autobiographical novel by the Reverend Paul Sawyer (1934-2010), a local Unitarian minister and peace activist who provided the initial inspiration for Seattle's first underground newspaper, Helix. He was present in the studio and providing occasional commentary. Milam, listening from home, realized that some of the language used might be judged obscene by FCC standards, and he ordered the broadcast cut short after barely more than an hour and replaced with Indian music. A few months later, in December, a speech by minister and civil rights leader Reverend James Bevel (1936-2008) was broadcast that contained some questionable nouns and adjectives. The FCC eventually came to the station, confiscated the tape, copied and returned it, and warned KRAB not to air it again, practically guaranteeing that it would.

KRAB did not want to pick a fight with the FCC unnecessarily, but thought the agency was overreaching. On January 24, 1969, all 27 staff and volunteers who held FCC broadcasting licenses gathered at the studio, signed the operating log together in solidarity, and aired the Bevel tape again. Three months after that, a broadcast interview with members of the San Francisco Mime Troupe (which had abandoned silence several years earlier) drew a listener's complaint to the FCC, alleging obscenity.

KRAB's three-year broadcasting license was up for renewal in 1969, and after sitting on the issue for months, the FCC issued a decision on January 21, 1970. Although it did not find that obscenities had been broadcast, it did rule that KRAB had not followed its own standards of avoiding material that was sensational "for its own sake" ("FCC Raps KRAB ... "). The punishment was to limit the station's license renewal to one year, rather than the usual three. This did not sit well with two members of the FCC panel, one of whom used his dissent to urge large commercial broadcasters to come to KRAB's assistance. The CBS network and others answered the call. An appeal was denied, but the agency ordered a hearing in Seattle to consider several factual issues that were in dispute. CBS attorneys filed a brief in KRAB's support.

On November 12, 1970, Milam testified to FCC hearing examiner Ernest Nash that KRAB had a policy of rejecting programs for reasons of "obscenity, obscurantism, sensationalism, and boorishness" ("F.C.C. Hears KRAB"). He also testified, perhaps less persuasively, that he recognized obscenity "by the emotional response he had ... characterized by sweating and coldness of his hands" ("Initial Decision," p. 341). More than 25 other witnesses testified on KRAB's behalf, including station manager Greg Palmer (1947-2009); Maxine Cushing Gray (1909-1987), associate editor of Seattle's Argus magazine; and Father John D. Lynch, a Catholic priest and regular KRAB commentator. Nash's decision, issued on March 22, 1971, was a complete vindication for the station. He found, among other things, that

"In considering their policies and their programming as an entirety, the licensee of KRAB seeks and most often attains those standards of taste and decency in programming that we should like to see reflected more often in our broadcast media" ("Initial Decision," p. 355).

The FCC declined to appeal Nash's ruling, and tiny KRAB in the far Northwest had won a significant victory for broadcasters across the nation.

Life After Lorenzo

Even before stepping away from active involvement with KRAB in March 1968, Milam was working and spending to spread the gospel of non-commercial radio to other cities. He sent volunteer David Calhoun south to help establish KBOO-FM in a basement room in downtown Portland, and it went on the air in June 1968 under the auspices of the Jack Straw foundation. Jeremy Lansman, KRAB's first engineer, wanted to start a station in St. Louis, where he had once lived, and with Milam's help, KDNA-FM started broadcasting there on February 8, 1969. Milam even ventured into commercial radio, purchasing KLGS-FM with a partner in the late 1960s, taking over sole control in 1970, renaming it KTAO, and running advertisements that were often indistinguishable from the station's typically Milam fare of things not heard elsewhere. In 1971, he would tell Washington Post columnist Nicholas von Hoffman:

"I've dropped almost a quarter of a million dollars on the four stations. I floated one loan from my mother and I'm systematically worked over by brothers and sisters who think I'm a wastrel, which I'm not. I'm in radio, but I'm down to my last $1,000" ("KRAB'S Founder Still in Radio").

It is not always easy to sort fact from creativity in Milam's pronouncements, but there is little doubt that he did more to advance the cause of listener-supported radio in the 1960s and early 1970s than any other single person. Although he sold KTAO to commercial broadcasters in 1973, he transferred its extensive record collection to a noncommercial station and remained dedicated to the cause. Milam later taught in San Diego and became involved in small, viewer-supported television stations. As of 2014, he was residing primarily in Mexico, shunning publicity but maintaining contact with many of his old cohorts.

After the FCC vindication, KRAB went on very much as before, resolutely different and usually broke or nearly so. In the early 1970s, Bob Friede, an heir to the Annenberg publishing fortune, became music director, a trustee of the Jack Straw Memorial Foundation, and eventually station manager. He was an unusual man with an unusual background, which included a stretch in Sing Sing penitentiary for manslaughter and drug violations, but he was a believer in listener-supported radio, and significant amounts of family money helped fill the subsidizing role that Milam had played in earlier times. But it was never enough, and the station seemed always one unanticipated expense away from oblivion.

"Community Radio"

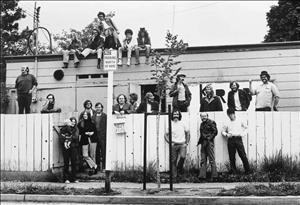

In June 1972, KRAB moved from the old donut shop to a decommissioned fire station on Capitol Hill. Congress had established the national Corporation for Public Broadcasting in 1967, and within a few years there was a proliferation of publicly subsidized, non-commercial media outlets, many associated with universities. By 1976, KRAB felt the need to differentiate itself from these institutional broadcasters, and began to characterize itself specifically as "community radio." This had an unintended consequence; it raised the expectations of a number of self-identified communities -- ethnic, social, political, sexual, among others -- that then pressed KRAB for airtime. The result, according to one former board member and station manager (who had started at KRAB as a volunteer while still in junior high school) was increased "balkanization" of programming (Reinsch interview).

Even the availability of funding from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting had drawbacks. The agency required that grant recipients have at least five full-time employees and broadcast a minimum of 18 hours a day. Compliance reduced KRAB's operational and financial flexibility. To add to the difficulties, the firehouse was falling apart and the City had other plans for it. After a difficult and extended search, in September 1980 KRAB moved its studio again, this time to 23rd Avenue and Jackson Street in Seattle's Central District. But more than 17 years of constant struggle to survive was taking its toll, and trouble was brewing.

The Unraveling

There was a huge conundrum at the heart of KRAB that was a recipe for a messy ending. Although it could only sometimes pay its bills, its 107.7 slot on the FM dial was both very valuable and, as available space on the spectrum became rare, increasingly coveted. In strictly financial terms, KRAB was worth much more dead than alive -- millions of dollars more.

There was also internal strife. Over the years there had been endless debates about how the station could attract more subscribers while honoring to the extent possible a maxim attributed to Milam: "The education of 10 is more important than the entertainment of 10,000" ("Just About Everybody ... "). It was to some extent purists against realists, with deep disagreements over whether KRAB's traditional practices and format could or should be strictly adhered to even as the ship went down. Many of the volunteers who over the years had devoted their time, talent, and labor to ensure the survival of purely non-commercial community radio in Seattle had developed proprietary feelings about the station, believed it should be run on collectivist principles, and were alert to anything they perceived as a threat to its traditions.

Things began getting particularly rough in the opening years of the 1980s, a time when there was "a lot of unhappiness all around" (Reinsch interview). In October 1981, after less than a year on the job, station manager Jamie Garner quit, upset over programming disagreements and convinced that the foundation intended to sell the station. In January 1982, the foundation board stepped in, took over operational control, and almost immediately announced that the station would go off the air for two weeks, then return with a reduced schedule. Foundation board chairman Chuck Reinsch said at the time, "This had been in the works for years. We've always been in a state of financial collapse." Gary Margason, one of the three original KRABers and a foundation trustee, agreed with the need for change: "The goal is to organize programming into a pattern which is more rational and appealing. It's not possible to do that while tending a 24-hour operation with 200 volunteers" ("KRAB, Confronting Financial Collapse ...").

Rumors swirled and rebellion brewed, and one of the most unconventional radio stations in American history seemed destined to end its organizational life in a conventional American manner -- in a courtroom, with lawyers. KRAB returned to the air on March 1, 1982, half time, with a revamped, less free-form schedule, and staffed mostly by Jack Straw board members. This was enough to trigger a lawsuit by the "KRAB Producers Association," a group of former volunteers and producers. The suit accused the foundation board of many things, including not following its own procedures, opacity, and insensitivity to the concerns of its volunteers. There were allegations that the foundation was intentionally not doing enough to help the station survive, thus making an eventual sale unavoidable. The Seattle Times aptly summarized the philosophical aspect of the dispute, characterizing the disagreements over KRAB's "original purpose" as "akin to scholars arguing over the different interpretations of the Torah" ("Strife at KRAB FM ...").

According to Chuck Reinsch, it was only after the two-week shutdown that the Jack Straw Memorial Foundation board began seriously contemplating the sale of KRAB. A little more than a year later, in April 1983, it was announced that a deal had been struck with Sunbelt Broadcasting, Inc., a commercial broadcasting company based in Colorado Springs, with a sale price of between $3.5 and $4 million. Even Lorenzo Milam, who had started it all more than 20 years before, supported the idea of selling the station's assets:

"Why not? If they feel that's the best thing, they could fund themselves and do wonders for the arts in Washington state. I feel very sympathetic. And I'd like to say I'm very glad not to be there" ("Strife at KRAB-FM ...).

The dissident KRAB Producers Association, now joined by others and renamed Community for KRAB Radio, attempted to block the deal. The rhetoric grew heated and decidedly uncivil, but those opposed to the sale simply did not have the legal horsepower to carry the fight to its end. In February 1984, the FCC announced that it would not stand in the way, and in a second blow, the group's attorney relocated to another state. The dissidents found themselves unable to continue the fight, and on February 23, 1984, they voluntarily, if reluctantly, dismissed the suit. The effort was not entirely in vain, however. Several issues the group raised (not the least of which was the future use of the funds realized from the sale) were of sufficient merit to earn the attention of the state attorney general's office, and the Jack Straw Memorial Foundation agreed that it would work to resolve those with the government.

On April 15, 1984, 35 years to the day after KPFA was launched in Berkeley, KRAB did its last broadcast. It was filled with the normal and varied range of programs, including vintage jazz and Turkish music, but starting at 9:20 p.m. the station's founders and a few long-time staff reminisced on the air in a free-form discussion filled with laughter and anecdote. Among the participants were Milam, Margason, and Gallant from the earliest days. Also on board were Tiny Freeman (d. 2013), a huge, one-time Republican congressional candidate (disavowed by the party) and host of a KRAB bluegrass program; Paul Dorpat, who had been building a reputation as Seattle's almost-official historian; and Libby Sinclair, Phil Bannon, and Bob West. For more than an hour and a half they nostalgically recalled some of the high points of the station's history. The programming then returned to music; host Kathryn Taylor closed the broadcast at 1:33 a.m. on April 16 with a simple "good night, and so long," followed by white noise. KRAB was gone forever.

The Legacy

KRAB was no more -- an exciting, bemusing, and often frustrating 21-year experiment in radio had come to a fractious end. But the Jack Straw Memorial Foundation, for years the impecunious owner of a fiscally floundering radio station, now had well more than $3 million in the bank. A relatively small amount went to repay Milam for loans he had made during the station's last dark months, but there was plenty left over, and the unfamiliar dilemma was what to do with it.

After trying unsuccessfully to partner with a radio station operated by students at Nathan Hale High School, the foundation established KSER-FM, a community station in Snohomish County, in 1991. In 1994, ownership was transferred to the nonprofit KSER Foundation, and it remained an independent, non-commercial community station. The Jack Straw Foundation (the "Memorial" having been dropped) was no longer in radio, but operated a thriving, non-profit "multi-disciplinary audio arts center," with a full-service recording studio, dedicated to the support of authors and artists working in a variety of media ("About Jack Straw Productions"). Some would argue that KRAB, through the foundation, has accomplished more in the 30 years since its death than it did during its 21-year life; others would strongly disagree, and even today some bad feelings linger among the survivors.

As of 2014, KRAB's history was being preserved on a website maintained by longtime stalwart Chuck Reinsch at http://www.krab.fm/. Photos, essays, program guides, reminiscences, and recordings of many of the station's broadcasts were gathered in an ongoing effort to document the saga of Seattle's pioneer commercial-free, listener-supported community radio station.