On December 15, 1868, Chinese settler Chun Ching Hock (1844-1927) opens the Wa Chong Company, a general-merchandise store, at the foot of Mill Street (later renamed Yesler Way) in Seattle. Chun (whose name was sometimes written Chin Chun Hock), believed to be Seattle's first Chinese immigrant, traveled in 1860 from China to San Francisco and then north to Seattle, where he found work in the Yesler Mill cookhouse. Chun Ching Hock's original partner in the Wa Chong Company is Chun Wa (d. 1873); Chin Gee Hee (1844-1929) will become junior partner following Chun Wa's death. The store sells Chinese goods, tea, rice, coffee, flour, and fireworks, but the company's most profitable business is labor contracting. It recruits and places Chinese immigrants in jobs ranging from domestic work to building railroads. Both Chun Ching Hock and Chin Gee Hee will survive Seattle's anti-Chinese riots in 1886 and the 1889 Seattle Fire, and both will become wealthy. Each will return to live permanently in China in the early 1900s, but the Wa Chong Company will operate in Seattle until 1953. The store's final location, the East Kong Yick Building at 719 S King Street, will become home to the Wing Luke Museum in 2008.

Seeking Gold Mountain

War and hard times in China coincided with the discovery of gold in California in the late 1840s and numerous subsequent discoveries over the next two decades in Idaho, Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia. Gold-rush news reached southeast China and thousands of young Chinese men came to the U.S. seeking work in a place they called Gim San ("Gold Mountain"). Willing to work long hours for low pay, Chinese immigrants satisfied the need for abundant cheap labor and played an important role in building the West.

Chun Ching Hock (whose name is also sometimes given as Chin Chun Hock or Chin Ching Hock) was born July15, 1844, in the Long Mei village of Toisan in Guangdong Province, China. He sailed to San Francisco at the age of 16, then headed north and in 1860 began working in the Yesler Mill cookhouse on the Seattle waterfront. The 1860 Washington Territorial census lists only one Chinese person living in Seattle, most likely Chun Ching Hock, who is considered to be the city's first Chinese settler. The same census counted King County's total population at about 300.

The Wa Chong Company

According to notes Chun made in his will, after working a number of years he had saved enough to visit family in China, where he gave money to his mother and brother, then borrowed from an uncle for his return to Seattle. On December 15, 1868, he opened a general-merchandise store called the Wa Chong Company (sometimes spelled "Wa Chung" and occasionally seen as Wa Chong & Company) in a wood-frame building located on the tideflats just south of the Yesler Mill. Wa Chong prospered in this central waterfront location as established settlers, newly arrived immigrants, and local Native Americans all traded at the store.

The Wa Chong Company sold Chinese goods, rice, sugar, tea, flour, and opium (legal until 1902), and was a major importer and distributor of fireworks. But the sale of merchandise was only a small part of the business, which became heavily involved in labor contracting. The Wa Chong Company recruited and placed Chinese immigrants in domestic work, logging, mining, construction, and later in fisheries and canneries. Through Wa Chong, workers were hired to build a segment of the Northern Pacific Railroad line between Kalama and Tacoma. One of the company's biggest projects was supplying workers in 1883 to dig a canal -- the Montlake Cut -- to transport logs between Union Bay on Lake Washington and Portage Bay on Lake Union.

Chinese workers also built many of Seattle's streets. Chun was quoted as saying, "I graded Pike, Union, Washington, and Jackson Streets ... At one time, the city owed me $60,000. I had to sue to recover it" (Chew, 130). The Wa Chong company received a commission for each worker placed. If employers could not pay in cash, they often paid in real estate, and Chun's company soon owned lots and even entire city blocks in Seattle.

The Wa Chong Company became the largest labor contractor in Washington Territory. Its workers required housing, and as the company prospered it constructed buildings that included lodging. As early as 1877, the company purchased a Duwamish farm as the site for a large company house, a hospital, and a joss house (Chinese temple).

Business Partners

Chun Ching Hock's first business partner, Chun Wa, died young in 1873. That same year, Chin Gee Hee -- a cousin of Chun Ching Hock from the Toisan district -- came to Seattle by way of northern California and Port Gamble and became the new junior partner at Wa Chong. By 1876 Seattle's population had grown to about 3,400, of whom about 250 were resident Chinese. There was also a floating population of about 300 additional Chinese, which included new arrivals and workers from other parts of King County who came into town for supplies.

The partnership between Chun Ching Hock and Chin Gee Hee was an uneasy one. Both were good businessmen, but Chin Gee Hee's major interests were developing the labor-contracting side of the business and building an import/export trade with China. In 1888, Chun Ching Hock bought his partner's share in the Wa Chong Company and Chin Gee Hee began his own business, the Quong Tuck Company. The building housing Quong Tuck was destroyed in the 1889 Great Seattle Fire, and Chin Gee Hee is credited with constructing the city's first brick structure completed after that catastrophe, the Canton Building located at 208-210 Washington Street.

Anti-Chinese Riots

While Chinese workers played an important role in the region's early development, they became increasingly resented as providers of cheap labor. When Washington Territory was created in 1853, Chinese were restricted from voting, and over the next three decades numerous laws were enacted further restricting their rights. When the economy tumbled in the 1880s and jobs became scarce, anti-Chinese sentiment increased nationwide, leading to the passage of the federal Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. Two anti-Chinese factions emerged. One, led largely by labor unions, advocated the immediate removal of the Chinese while a second group wanted to proceed more peacefully to the same end. But both wanted the Chinese to leave.

Actions against Chinese workers became increasingly violent throughout Washington Territory, and on February 7, 1886, a mob of citizens invaded Seattle's Chinese quarter and 350 Chinese were forced to leave town aboard the steamer Queen of the Pacific. On February 14, 110 more were sent away, with the remaining number told to leave on a following steamer.

Chin Gee Hee was caught by the mob, but due to his stature in the community he was released by the Home Guard. He insisted he would not leave Seattle until he was paid money owed to him. While Territorial Governor Watson C. Squire (1838-1926) declared martial law and brought in federal troops to quiet the unrest, Chin Gee Hee sought help with a direct appeal to the Chinese consul-general in San Francisco. He also kept a record of damage done to Chinese businesses during the rioting and later was able to collect $700,000 through a ruling by Judge Thomas Burke (1849-1925). But when the rioting ended in Seattle, only a handful of Seattle's Chinese merchants and workers remained.

Location, Location, Location

The Wa Chong Company's store was, in its early years, a community center, and its locations over the years mirror the growth of Seattle's Chinatown-International District. From its original waterfront location, Wa Chong made several moves. As author Ron Chew recounts:

"Chin Chun Hock made a fortune that included substantial real estate holdings. In addition to two buildings he owned on Third Avenue and Washington Street, he also owned a building on Fourth Avenue and South Main Street, where he ran the Wa Chong Company for nearly 20 years before moving to King Street" (Chew, 130).

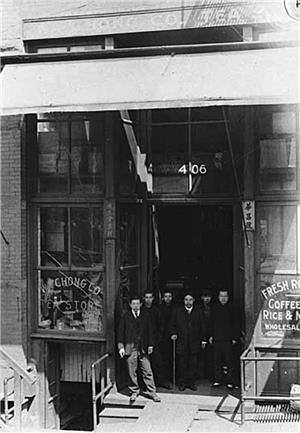

Seattle city directories list Wa Chong's address from 1900 to 1910 as 406-408 Main Street. When the Great Northern Railway announced plans in March 1902 to dig a railroad tunnel from the foot of Pine Street to Third Avenue and Washington Street, many Chinese-owned buildings, including some belonging to the Wa Chong Company, were demolished. As the city's population grew and rental values increased, Chinatown began moving farther east. In 1910, the Kong Yick Investment Company developed areas around King Street, and the Wa Chong Company was one of several businesses that moved into the East Kong Yick Building erected at 719 King Street.

This became the final location for the Wa Chong Company, which continued in business until 1953. The building -- once housing both the Wa Chong and Quong Tuck companies -- was remodeled and opened in 2008 as the new home of the Wing Luke Museum.

Investing in China

In 1900 Chun Ching Hock returned to live permanently in Canton, China, but remained an owner of the Wa Chong Company, which was managed in Seattle by Woo Gen. While living in Canton, Chun occasionally visited Seattle, where he continued to own a large amount of real estate. Chun also expanded the Wa Chong Company's operations to Asia. Through the company, he began logging operations in Shanghai and Hong Kong.

Chin Gee Hee also found opportunities in China. Around 1904 he returned there to live, turning Seattle management of the Quong Tuck Company over to his son Chin Lem. Through the company, Chin Gee Hee built the Sun Ning Railway in southern China, raising money from Chinese contributors and using American materials for its construction. The Sun Ning Railway was the first major railway in China's Pearl River Delta area. It would be destroyed during the Second Sino-Japanese War and dismantled in 1938. Despite the threat of boycotts, Chun Ching Hock and Chin Gee Hee worked for open trade between China and the Puget Sound region, and both became wealthy.

An Old Pioneer and His Family

In 1924, at 80 years of age, Chun Ching Hock visited Seattle for the last time. A reporter for The Seattle Times greeted the old pioneer and wrote the story of his life. He described Chun as having "the step of a man 50 years younger" and quoted him as saying, "My, but Seattle looks good to me. How is Judge Burke and how many of the old pioneers besides him and me are still here?" The reporter went on to note that Chun "remains today one of the heavy owners of Seattle property, his land value being said to reach several hundred thousand dollars" ("A Real Pioneer Returns").

Chun stayed in Seattle until February 1927, when he returned to Canton to celebrate the Chinese New Year. After partying for five days straight he contracted influenza and died on February 13, 1927. He is buried in the Chinese Permanent Cemetery at Aberdeen in Hong Kong.

A year after opening the Wa Chong Company, Chun Ching Hock had married a woman named Mary Carey, thought to be a member of the Duwamish tribe. The couple had three sons: Chun Lung Coe (1873-1883), Chun Lung Key (1877-1937), and Chun Lung Kaa (1884-1930), all born in Port Orchard. While visiting in China, Mary contracted a virus and died. In 1899 Chun Ching Hock married a Chinese woman named Lun Shi. One of his grandsons, Tsai Hwa Lee, later said that over his lifetime Chun had several wives, 11 concubines, 7 sons, and 12 daughters. As of 2014 descendants of Chun Ching Hock continued to live in Washington.