This account of Bob Moch, the coxswain on the University of Washington's 8-man crew that won gold in the 1936 Berlin Olympics, was written by Stephen Sadis. It appears in Distant Replay! Washington's Jewish Sports Heroes, a book curated, designed, and edited by Sadis and published in 2014 by the Washington State Jewish Historical Society. Distant Replay! contains brief biographies, authored by several writers, of more than 150 Jewish athletes, sports executives, writers, and others who have contributed to Washington's rich athletic heritage. The publisher has graciously allowed HistoryLink.org to present a number of these biographical sketches as People's Histories, and they appear here as they do in the book.

Bob Moch

Reflecting on the athletic triumphs over the past 100 years, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer deemed it Washington state's greatest sports achievement of the century. In front of 75,000 German fans chanting, "Deutsch-land! Deutsch-land!" the University of Washington's 8-man crew came from behind to win gold in the 1936 Berlin Olympics. At the helm, was coxswain Bob Moch, who found out shortly before embarking on the trip to Europe that he was Jewish -- a fact hidden by his father since immigrating to the United States.

Though the story has faded and resurfaced over the decades, the 2013 publishing of The Boys in the Boat has brought national focus to the Olympic feat, with a chance for even more attention with a movie on the horizon.

Born in 1914 in the town of Montesano, 30 miles inland from Grays Harbor and the Washington coast, Robert was the son of Gaston and Fleeta Moch. His father had emigrated from Switzerland and within years of arriving, married and opened a jewelry store in the small town of 2,500. Enrolled at the UW in 1932, Robert took up fencing and rowing, landing a spot on the 8-man crew coached by Al Ulbrickson. "I knew for years I was going to turn out to see if I could be a coxswain for the University of Washington crew ... . I was always interested in athletics and there was only one place I could go," remembered Moch in a 2002 interview.

At the start of the season, Ulbrickson had selected a different team as the varsity crew. Moch and his teammates were disappointed, knowing they were the faster team, but none of them had ever rowed before stepping onto campus and lacked the experience of the others. The eight oarsmen and the coxswain bonded over the slight and came up with a mantra, "L-G-B," that they would repeat quietly amongst themselves. If anyone asked, they explained it stood for, "Let's get better," when it really meant, "Let's go to Berlin." Inter-squad time trials eventually turned the tide, prompting Ulbrickson to name Moch's crew as the varsity team.

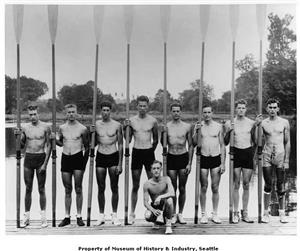

Since its earliest days, rowing had always been an elite sport with the nation's top teams crewed by the sons of the affluent from Ivy League schools. The Husky team, in contrast, was comprised of kids from working and middle class families -- farm boys, fishermen, and loggers struggling to survive the Great Depression. Many of the oarsmen earned their tuition washing windows, scrubbing floors and selling tickets at football games. In addition to Moch, the team included, Don Hume, Joe Rantz, George "Shorty" Hunt, Jim McMillin, John White, Gordy Adams, George Day and Roger Morris. Moch was the only senior.

In June of 1936, after the Huskies beat UC Berkeley on Lake Washington, they traveled to Poughkeepsie, NY to compete in the Intercollegiate Rowing Association's Championship Regatta. Held on the Hudson River, the competition was viewed as rowing's national title event. Trailing by as much as five lengths at the midway point, they raised their stroke from 28 to 34 and their shell, dubbed, the "Husky Clipper," seemed to lift out of the water. "We took off … we just flew by them," said Moch. The wins by the UW freshman, JV and varsity crews combined for the first ever sweep of the rowing championship by a west coast crew. The victory also gave Coach Ulbrickson and the varsity eight the UW's first undefeated season.

Ulbrickson's strategy of keeping the stroke count low in the beginning of the race and "mow 'em down in the finishing sprints," would be tested when the men traveled to Princeton in July for the Olympic trials. The crew trailed by as much as five lengths at the midway point, but in the final 400 meters, Moch called upon Don Hume -- who set the pace for the seven oarsmen behind him -- to turn the stroke up to 40. Again, the shell surged to the finish line, winning by a length.

Following the Huskies victory, the U.S. Olympic Committee contacted the UW to inform the team that they needed to come up with $5,000 for the trip to Berlin. Sports editors for both Seattle papers penned their outrage in editorials and enlisted newsboys to ask for donations while selling papers on street corners. Funds came in from all across the state and in three days enough had been raised.

Before taking up rowing, most of these young men had never traveled beyond Washington's borders. Now they stood on the deck of the S.S. Manhattan as it set sail for Europe. Also making the voyage was the designer and builder of the Husky Clipper, George Pocock. Pocock crafted his first shell for the UW in 1912 and while slowly growing his boat-building business, William Boeing walked into his shop and asked him to build pontoons for seaplanes during World War I. The Husky Clipper was specially designed for the 1936 Olympics, and after winning gold, Pocock's reputation soared. At one point, 80% of all college crews were racing in Pocock boats, while US rowers returned to the Olympics in the Seattle-made shells, winning gold in 1948, 1952, 1956, 1960 and 1964. With Pocock's constant attention to its security, the Husky Clipper arrived in Hamburg undamaged; Hume and teammate John White however, became ill, while many of the others suffered seasickness.

Donned in uniforms now representing the United States, the boys from the UW would first face Great Britain, a team Ulbrickson and Pocock felt were their toughest competitors. The intense competition pushed both teams to their limits with the US taking the heat as well as setting a new Olympic and world record. Italy, Germany, Hungary and Switzerland also advanced to the finals. The brutal qualifying race exacerbated Hume's illness, who passed out at the finish line and was revived by Moch splashing cold water on his face.

The regatta's final event and the final event of the 1936 Olympics was set for August 14th and would be broadcast live around the world. Seattle retailer Weisfield and Goldberg ran an Olympic special on Philco radios, offering home installation up to 8 o'clock the night before the 9 am broadcast. With so many families having made donations to finance the crew's trip to Berlin, excitement for the race was pervasive throughout the Northwest. "People in the city felt that they were stockholders in the operation," recalled Gordon Adam, who rowed in the three-seat.

Up until the final race, Americans were focused on the brilliance of African American athlete, Jesse Owens, who took four gold medals in track and field events. The victories were made that much sweeter as the US had earlier threatened to boycott the games after Hitler declared that Blacks and Jews would not be allowed to compete. While Owens and the American track team reigned on the field with 20 gold, 10 silver and 4 bronze medals, the Germans dominated on the water, winning five gold medals and one silver. Cesar Saerchinger, who, along with Bill Henry covered the rowing events for CBS, recalled later that with every German victory they had to, "stand up for the German anthem and 'Horst Wessel' [the Nazi party anthem] after every event, until we were nauseated."

On the morning of the race, Hume was shivering uncontrollably. He had lost 14 pounds. During warm ups that afternoon he could barely pull his oars. Ulbrickson considered an alternate oarsman, but "Johnny White went to [the coach] and told him Don had to be in the boat," recalled Moch. "He said, 'Tie him in, and we'll get him across the finish line.'"

By 6 pm, over 75,000 people gathered along the banks of Lake Grunau. Hitler, Hermann Goring, Joseph Goebbels and a host of other Nazi officials watched from the grandstand. At the starting line, Moch looked over at Hume whose eyes were closed and his body listless. The Germans were in lane one, the Italians in two and the US at the end in lane six. Positioned farthest from the race official, the Husky crew didn't hear the starting commands, but managed a decent start nevertheless. Germany bolted for the lead, followed by Italy, Great Britain and the US. Millions listening by radio smiled apprehensively at Henry's broadcast; "We all know the Washington crew is probably the slowest-starting crew in the world. It gives everybody heart failure."

At the halfway mark of the 2000-meter race, Hume had kept the stroke down to 36, while the Germans and the Italians opened a boat-and-a-half lead. With 800 meters to go, Moch saw Hume's eyes pop open, his jaw clamp shut and he began to increase the stroke. Seattle listeners moved closer to their radios and clung to Henry's call:

"It looks as though the United States [is] beginning to pour it on now! The Washington crew is driving hard on the outside of the course. They are coming very close now to getting into the lead! They have about 500 meters to go, perhaps a little less than 500 meters, and there is no question in the world that Washington has made up a tremendous amount of distance … . They have moved up definitely into third place. Italy is still leading, Germany is second, and Washington — the United States — has come up very rapidly on the outside. They are crowding up to the finish now with less than a quarter of a mile to go!"

In the final 200 meters, the crowd noise was so loud that Moch's megaphone was useless and the coxswain instead had to bang on the side of the shell to signal the desired cadence. Hume pushed the stroke to a near impossible rate of 44. Nearing the finish line, Moch called for "a 20" (20 powerful strokes) and the rowers thought those would be the last of the race.

"We hit 17 and 18, and then he said 20 more on top of that," recalled Jim McMillin, who sat in the five-seat. The US passed the Germans in the final 10 strokes and were drawing even with the Italians as they crossed the finish line together. The crowd's roar was deafening, but still none of the oarsmen knew who had won. McMillin said, "I can still remember Bob saying in kind of a half-whisper, 'I think we won,' but no one was sure."

With the crowd now quieted in anticipation, the speakers above the grandstand announced that the US had won, followed by Italy and Germany. After racing for a mile and a quarter across the lake, the finishing times of the three nations were separated by just one second. Exhausted, the crew managed to row to the dock in front of the grandstand, where laurel wreaths were draped around the victors.

The next day, the nine men from the University of Washington gathered in the Olympic stadium to receive their gold medals. In front of the massive German crowd numbering 100,000, Bob Moch, the Jewish coxswain and his eight oarsmen stood proudly while the "Star-Spangled Banner" played and the American flag was raised.

Moch was credited with being the mind of the team, for pulling his teammates together and for getting them to respond to an unfathomable stroke count. "Bob got some things out of the crew that I didn't think were there," recalled Roger Morris, who rowed in the eight-seat. "We owe him a ton for helping win that race in Berlin," McMillin said. "We were in deep trouble, and he was able to pull us out of it."

Moch went on to help coach the Washington freshman and lightweight crews from 1937-1939, then spent five years at M.I.T. as the head rowing coach. Moch graduated from the UW business school and partnered with the Seattle law firm, Roberts, Shefelman, Lawrence, Gay and Moch.

Starting in 1969, the nine crew members agreed to meet once a year -- and did so nearly every year until they began passing away. In 2005, Moch died at his home in Issaquah. Roger Morris, who sat in the bow of the shell, had the distinction of being the first to cross the finish line, and after passing in 2009, was the last surviving member of the UW's legendary crew.

In a 2002 interview, Moch reflected on what he gained from the sport, "Crew has been a great influence on my life. It's one of the two greatest influences outside of my family that dictated what I did and how I did it. And this group of men I was associated with, they've been my best friends all my life -- we were all like brothers … and I miss them."