On June 17, 1869, Charles Watts murders his San Juan Lime Company partner Augustin Hibbard at the company office. The partners are arguing about the amount and quality of Watts's contribution to the limekiln operation located at what will become known as Lime Kiln on the west shore of San Juan Island. When Hibbard accuses Watts of stealing several personal items, Watts interprets Hibbard's actions as a threat of aggression and fires two shots directly into Hibbard's face and another into his chest. Hibbard barely manages to stagger down the steps of the boarding house, where the office is located, only to collapse and die several hours later. Another untimely death roils the developing lime industry in the San Juan Islands. The murder and its aftermath shed light on the small-scale lime operations that prevailed in the islands prior to the establishment of the Tacoma and Roche Harbor Lime Company in 1886.

San Juan Lime Company

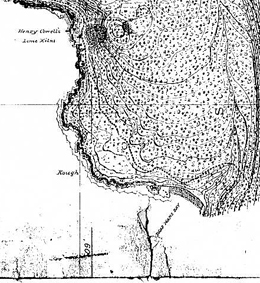

In 1860, Lyman Cutlar, the man who a year before had shot the boar and sparked the Pig War boundary dispute in which both the United States and Great Britain claimed the San Juan Islands, partnered with E. C. Gillette and Frank Newsome to produce lime on the west side of San Juan Island near Deadman Bay at what would come to be known as Lime Kiln Point and, more than a century later, the site of Lime Kiln Point State Park. Gillette sold his interest to Augustin Hibbard after the first winter of operation, and Hibbard, Cutlar, and Newsome formed a new business -- the San Juan Lime Company -- on January 13, 1861.

Hibbard bought out Cutlar and Newsome at the end of 1864, and continued operations until the following year, when George R. Shotter & Company bought in. In 1868 Hibbard borrowed $1,500 for operations from Catherine McCurdy of Port Townsend, secured through a mortgage on the land, and bought out Shotter. A year later on March 9 he formed a partnership, still known as the San Juan Lime Company, with Nicholas C. Bailey, Charles Huntington, and Charles Watts. This agreement was shattered three months later when Watts murdered Hibbard.

Court Proceedings

The subsequent murder trial went through a number of lengthy jurisdictional venues due to the uncertain status of the "Disputed Islands," as the San Juans were then called, eventually ending up with an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court. Seven years later, after the Supreme Court upheld the guilty verdict, Watts managed to escape his prison keepers -- and his hanging -- and was never seen or heard from again.

Meanwhile, because Hibbard died intestate, the probate court appointed an executor, Charles Bartlett, to settle his estate. There were three heirs, all from New England: Harriet Truesdale, Ashley Hibbard, and Sophia A. Maskey. Sophia's husband, Thomas Maskey, came west with her to represent the heirs and manage the limekiln operations. Maskey and court-appointed appraisers prepared inventories of the property, and the heirs petitioned for distribution of the estate in April of 1871. However, Thomas Maskey died before that could occur. Despite the effort of the heirs to prevent it, the court eventually ordered the sale of the property to cover numerous debts and the mortgage held by Catherine McCurdy.

The property was sold for $1,500 in 1873 to none other than McCurdy, who thereby paid off her own mortgage and obtained full title to the land and improvements in the process. She turned it over to her son James to operate with former San Juan Lime Company partner N. C. Bailey. The two men soon secured a contract to supply lime for the new territorial prison at Steilacoom; within a few years, they had expanded production to 20,000 barrels per year.

McCurdy Era at Lime Kiln

Then, in 1875, Bailey died. He left his half of the company and property to his wife, Jane, and their two children. Within a few years, Jane Bailey married James McCurdy, which united their ownership of the San Juan Lime Company. Although the boundary dispute between the United States and Great Britain was settled in 1872, the San Juan Islands were not officially surveyed until several years later, and the Lime Kiln site itself not platted until November 29, 1875. On June 17, 1879, James McCurdy applied for a 152-acre homestead to the north of the original kiln site. Then, on August 6 of the same year, he applied under the Timber and Stone Act of 1878 for land relinquished by Jane Bailey, and subsequently returned a half interest to her in December 1880, as his wife.

The June 16, 1877, Washington Standard described the San Juan Lime Company as producing 70 barrels and burning four cords of wood daily. With 15 to 20 men employed, company expenses ran about $1,200 per month. Two years later, on March 28, 1879, while noting that the kiln had been shut down for repairs, the newspaper reported that some 20,000 barrels were produced annually, and projected 30,000 in 1880. That proved optimistic.

A review of the 1870 and 1880 federal censuses provides a glimpse of the small kiln's business operations. According to the 1870 census, the San Juan Lime Company produced $26,000 worth of lime -- 13,000 barrels at $2 a barrel -- and employed 18 men for six months of a year for a total payroll of $11,000. These employees included one lime maker, two coopers, two carpenters, four quarrymen, a chopper, three laborers, and two cooks. Among the various ethnic groups working there -- most of whom were American or Canadian -- two groups stand out: the quarrymen were all from Cornwall and both cooks were from China.

By the time of the 1880 census, the operation was producing only $18,000 worth of lime, and paid $6,000 to the 21 employees who worked there nine months of the year. The typical work day was 10 hours, 9 in the winter; a day's wage for an "average day laborer" was 75 cents, but a "skilled mechanic" could earn as much as $3.50. Among the enumerated workers were McCurdy and his family, as well as a cook, carpenter, four coopers, and a woodcutter.

During the early 1880s, McCurdy's operation began to slip, and production dropped to 7,000 barrels per year. The McLachlan brothers, who were producing lime at Eureka, located north of Friday Harbor on the east coast of San Juan, offered strong competition. Perhaps in desperation, McCurdy began borrowing heavily from several sources. In November 1883, he obtained a $6,000 on a promissory note, secured by his property and improvements, from Corbitt and MacLeay of Portland, who later sold the mortgage to the Tacoma Lime Company. Then in November of the following year, McCurdy signed a second mortgage with his mother, for $2,500. However, in the same year, 1884, two companies -- the Mattulah Manufacturing Company and the Puyallup Manufacturing Company -- sued (and were, as a result, paid) for reimbursement for supplies. McCurdy had also made promissory notes to Israel Katz, a local entrepreneur, in 1884 and then again in 1886, when Katz sued for payment.

McCurdy's mother sold her latest promissory note and mortgage to John S. McMillin (1855-1936), who also held the Tacoma Lime Company mortgage. McMillin, who had purchased and expanded the lime operations on the north end of the island under the auspices of the Tacoma and Roche Harbor Lime Company, then leased the Lime Kiln property from James and Jane McCurdy for three years, beginning in September 1886.

Cowell Takes Control

One month later, the McCurdys sold their property to Henry Cowell of San Francisco. Cowell in turn sold a half interest to his California partner Lloyd Tevis. Cowell refused to pay the mortgages on the property, forcing foreclosure by the Tacoma and Roche Harbor Lime Company; he then turned around and picked up the property at the subsequent bankruptcy sale.

McMillin responded by filing suit against Cowell, Tevis, Lee Ingram, and Richard and Robert Scurr -- the latter three hired to work the quarries at that time -- claiming that they were depleting the resources on land leased to McMillin. In this, the first of several legal battles between McMillin and Cowell, the judge eventually found for the defendants and dismissed the case. The McCurdy Lime Company became known as "Cowell's," entering into another, relatively more stable, era of lime production on San Juan Island.

A light station was established at Lime Kiln Point in 1914, and five years later a 38-foot-high lighthouse tower, still operational in 2014, was completed. By then lime production was winding down. In 1985, long after the end of the San Juan lime industry, the property around the lighthouse became Lime Kiln Point State Park, soon informally known as "Whale Watch Park," a prime spot for watching Puget Sound's iconic resident Orca whales, which frequently pass close to the shoreline there as they hunt salmon in Haro Strait.